32.2Transcription Factors Bind DNA and Regulate Transcription Initiation

Transcription Factors Bind DNA and Regulate Transcription Initiation

DNA-

Eukaryotic transcription factors usually consist of several domains. The DNA-

A range of DNA-binding structures are employed by eukaryotic DNA-binding proteins

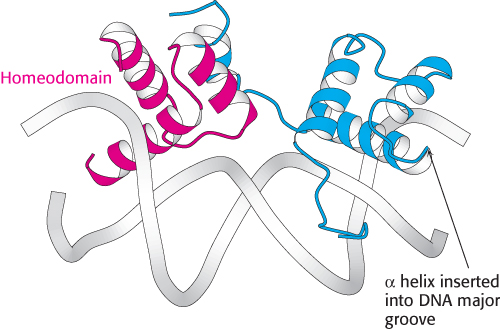

FIGURE 32.6 Homeodomain structure. The structure of a heterodimer formed from two different DNA-

FIGURE 32.6 Homeodomain structure. The structure of a heterodimer formed from two different DNA-The structures of many eukaryotic DNA-

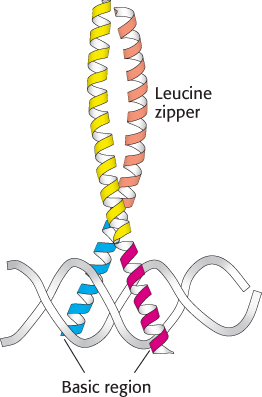

The second class of eukaryotic DNA-

FIGURE 32.7 Basic-

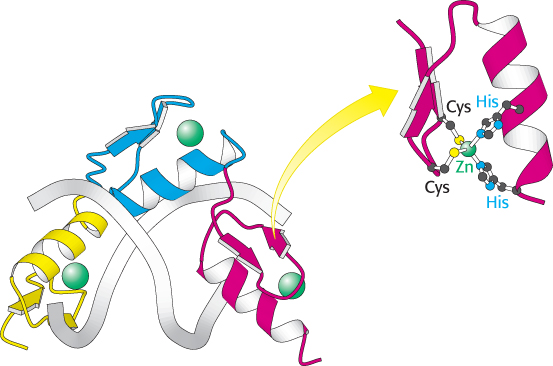

FIGURE 32.7 Basic-The final class of eukaryotic DNA-

FIGURE 32.8 Zinc-

FIGURE 32.8 Zinc-946

Activation domains interact with other proteins

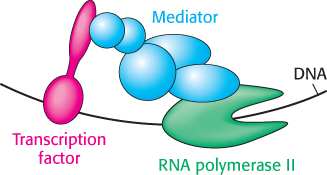

The activation domains of transcription factors generally recruit other proteins that promote transcription. In some cases, these activation domains interact directly with RNA polymerase II or closely associated proteins. The activation domains act through intermediary proteins that bridge between the transcription factors and the polymerase. An important target of activators is mediator, a complex of 25 to 30 subunits conserved from yeast to human beings, that acts as a bridge between transcription factors and promoter-

Activation domains are less conserved than DNA-

We have been considering the case in which gene control increases the expression level of a gene. In many cases, the expression of a gene must be decreased by blocking transcription. The agents in such cases are transcriptional repressors. Like activators, transcriptional repressors act in many cases by altering chromatin structure.

Multiple transcription factors interact with eukaryotic regulatory regions

The basal transcription complex described in Chapter 29 initiates transcription at a low frequency. Recall that several general transcription factors join with RNA polymerase II to form the basal transcription complex. Additional transcription factors must bind to other sites that can be near the promoter or quite distant for a gene to achieve a higher rate of mRNA synthesis. In contrast with the regulators of prokaryotic transcription, few eukaryotic transcription factors have any effect on their own. Instead, each factor recruits other proteins to build up large complexes that interact with the transcriptional machinery to activate transcription.

A major advantage of this mode of regulation is that a given regulatory protein can have different effects, depending on what other proteins are present in the same cell. This phenomenon, called combinatorial control, is crucial to multicellular organisms that have many different cell types. Even in unicellular eukaryotes such as yeast, combinatorial control allows the generation of distinct cell types.

Enhancers can stimulate transcription in specific cell types

Transcription factors can often act even if their binding sites lie at a considerable distance from the promoter. These distant regulatory sites are called enhancers (Chapter 29). Enhancers function by serving as binding sites for specific transcription factors. An enhancer is effective only in the specific cell types in which appropriate regulatory proteins are expressed. In many cases, these DNA-

947

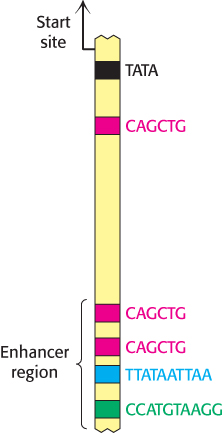

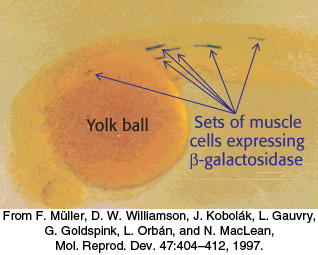

The properties of enhancers are illustrated by studies of the enhancer controlling the muscle isoform of creatine kinase (Figure 32.10). The results of mutagenesis and other studies revealed the presence of an enhancer located between 1350 and 1050 base pairs upstream of the start site of the gene for this enzyme. Experimentally inserting this enhancer near a gene not normally expressed in muscle cells is sufficient to cause the gene to be expressed at high levels in muscle cells but not in other cells (Figure 32.11).

Induced pluripotent stem cells can be generated by introducing four transcription factors into differentiated cells

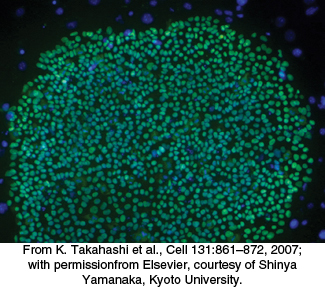

An important application illustrating the power of transcription factors is the development of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Pluripotent stem cells have the ability to differentiate into many different cell types on appropriate treatment. Previously isolated cells derived from embryos show a very high degree of pluripotency. Over time, researchers identified dozens of genes in embryonic stem cells that contributed to this pluripotency when expressed. In a remarkable experiment reported for mouse cells in 2006 and human cells in 2007, Shinya Yamanaka demonstrated that just four genes out of this entire set could induce pluripotency in already-

An important application illustrating the power of transcription factors is the development of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Pluripotent stem cells have the ability to differentiate into many different cell types on appropriate treatment. Previously isolated cells derived from embryos show a very high degree of pluripotency. Over time, researchers identified dozens of genes in embryonic stem cells that contributed to this pluripotency when expressed. In a remarkable experiment reported for mouse cells in 2006 and human cells in 2007, Shinya Yamanaka demonstrated that just four genes out of this entire set could induce pluripotency in already-

These iPS cells represent powerful research tools and, potentially, a new class of therapeutic agents. The proposed concept is that a sample of a patient’s fibroblasts could be readily isolated and converted into iPS cells. These iPS cells could be treated to differentiate into a desired cell type that could then be transplanted into the patient. For example, such an approach might be used to restore a particular class of nerve cells that had been depleted by a neurodegenerative disease. Although the field of iPS cell research is still evolving, it holds great promise as a possible approach to treat any common and difficult-

948