33.4Hearing Depends on the Speedy Detection of Mechanical Stimuli

Hearing Depends on the Speedy Detection of Mechanical Stimuli

Hearing and touch are based on the detection of mechanical stimuli. Although the proteins of these senses have not been as well characterized as those of the senses already discussed, anatomical, physiological, and biophysical studies have elucidated the fundamental processes. A major clue to the mechanism of hearing is its speed. We hear frequencies ranging from 200 to 20,000 Hz (cycles per second), corresponding to times of 5 to 0.05 ms. Furthermore, our ability to locate sound sources, one of the most important functions of hearing, depends on the ability to detect the time delay between the arrival of a sound at one ear and its arrival at the other. Given the separation of our ears and the speed of sound, we must be able to accurately sense time differences of 0.7 ms. In fact, human beings can locate sound sources associated with temporal delays as short as 0.02 ms. This high time resolution implies that hearing must employ direct transduction mechanisms that do not depend on second messengers. Recall that, in vision, for which speed also is important, the signal-

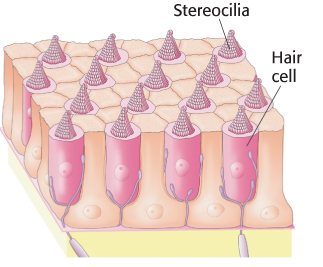

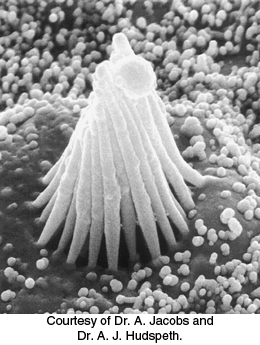

Hair cells use a connected bundle of stereocilia to detect tiny motions

Sound waves are detected inside the cochlea of the inner ear. The cochlea is a fluid-

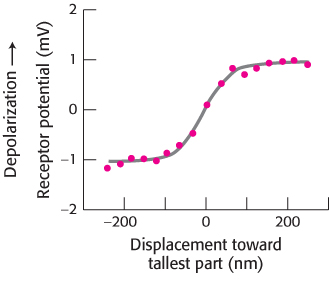

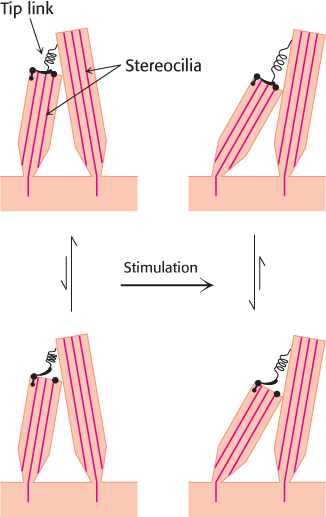

Micromanipulation experiments have directly probed the connection between mechanical stimulation and membrane potential. Displacement toward the direction of the tallest part of the hair bundle results in the depolarization of the hair cell, whereas displacement in the opposite direction results in its hyperpolarization (Figure 33.31). Motion perpendicular to the hair-

976

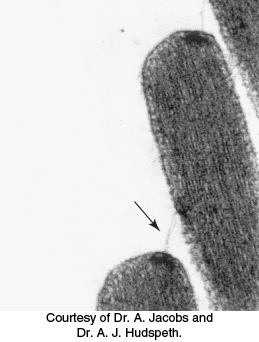

How does the motion of the hair bundle create a change in membrane potential? The rapid response, within microseconds, suggests that the movement of the hair bundle acts on ion channels directly. An important observation is that adjacent stereocilia are linked by individual filaments called tip links (Figure 33.32).

The presence of these tip links suggests a simple mechanical model for transduction by hair cells (Figure 33.33). The tip links are coupled to ion channels in the membranes of the stereocilia that are gated by mechanical stress. In the absence of a stimulus, approximately 15% of these channels are open. When the hair bundle is displaced toward its tallest part, the stereocilia slide across one another and the tension on the tip links increases, causing additional channels to open. The flow of ions through the newly opened channels depolarizes the membrane. Conversely, if the displacement is in the opposite direction, the tension on the tip links decreases, the open channels close, and the membrane hyperpolarizes. Thus, the mechanical motion of the hair bundle is directly converted into current flow across the hair-

Mechanosensory channels have been identified in Drosophila and vertebrates

The search for ion channels that respond to mechanical impulses has been pursued in a variety of organisms. Drosophila have sensory bristles used for detecting small air currents. These bristles respond to mechanical displacement in ways similar to those of hair cells; displacement of a bristle in one direction leads to substantial transmembrane current. Strains of mutant fruit flies that show uncoordinated motion and clumsiness have been examined for their electrophysiological responses to displacement of the sensory bristles. In one set of strains, transmembrane currents were dramatically reduced. The mutated gene in these strains was found to encode a protein of 1619 amino acids, called NompC for no mechanoreceptor potential.

The carboxyl-

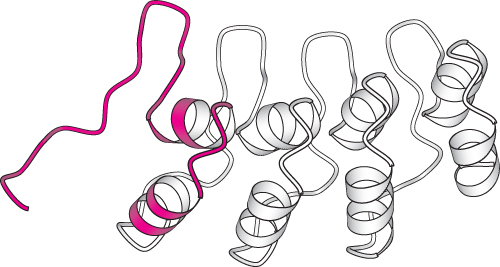

FIGURE 33.34 Ankyrin repeat structure. One ankyrin domain is shown in red in this series of four ankyrin repeats. Notice the hairpin loop followed by a helix-

FIGURE 33.34 Ankyrin repeat structure. One ankyrin domain is shown in red in this series of four ankyrin repeats. Notice the hairpin loop followed by a helix-977

A candidate for at least one component of the mechanosensory channel taking part in hearing has been identified. The protein, TRPA1, is a member of the TRP channel family. The sequence of TRPA1 also includes 17 ankyrin repeats. TRPA1 is expressed in hair cells, particularly near their tips. Further studies are under way to test and extend the exciting hypothesis that this protein is a component of the sought-