10.3 Sexual Interactions

As explained in Chapter 9, the hormones of puberty awaken sexual interest. Adolescent sexual interactions are not only normal, they are joyous and instructive, preparing young people for healthy adult relationships. Of course, teenage romance is complicated and early sex is problematic, as soon described. But first, let us celebrate: Teenagers today are sexually healthier than teenagers a few decades ago.

- In general, there has been a downward trend in teen births around the world. For example, between 1960 and 2010, the adolescent birth rate in China was cut in half (reducing the United Nations’ projections of the world’s population in 2050 by about 1 billion). In Canada between 1996 and 2006, the teen pregnancy rate declined by 37 percent, continuing a long-

term downward trend evident since the 1970s. However, between 2006 and 2010, the national teen pregnancy rate edged slightly upwards, and four provinces experienced increases of more than 15 percent (McKay, 2013). Curiously, most experts feel the economic recession had a lot to do with the upsurge. According to Alex McKay, research coordinator for the Sex Information and Education Council of Canada: “Young women who feel optimistic about their futures with respect to access to education and career tend not to get pregnant. Young women who are starting to feel discouraged about their employment and education opportunities are more likely to get pregnant. That is a straightforward correlation that persists wherever in the Western world you go” (Bielski, 2013). - The use of protection has risen. Contraception, particularly condom use among adolescent boys, has increased markedly everywhere since 1990 (Santelli & Melnikas, 2010). In Canada, among males aged 15 to 24 with just one sexual partner, condom use increased from 59 percent in 2003 to 67 percent in 2010 (Rotermann, 2012).

- The teen abortion rate is down. From 2001 to 2010, the teenage abortion rate in Canada decreased by more than 24 percent, from 19.4 per 1000 to 14.7 (McKay, 2013).

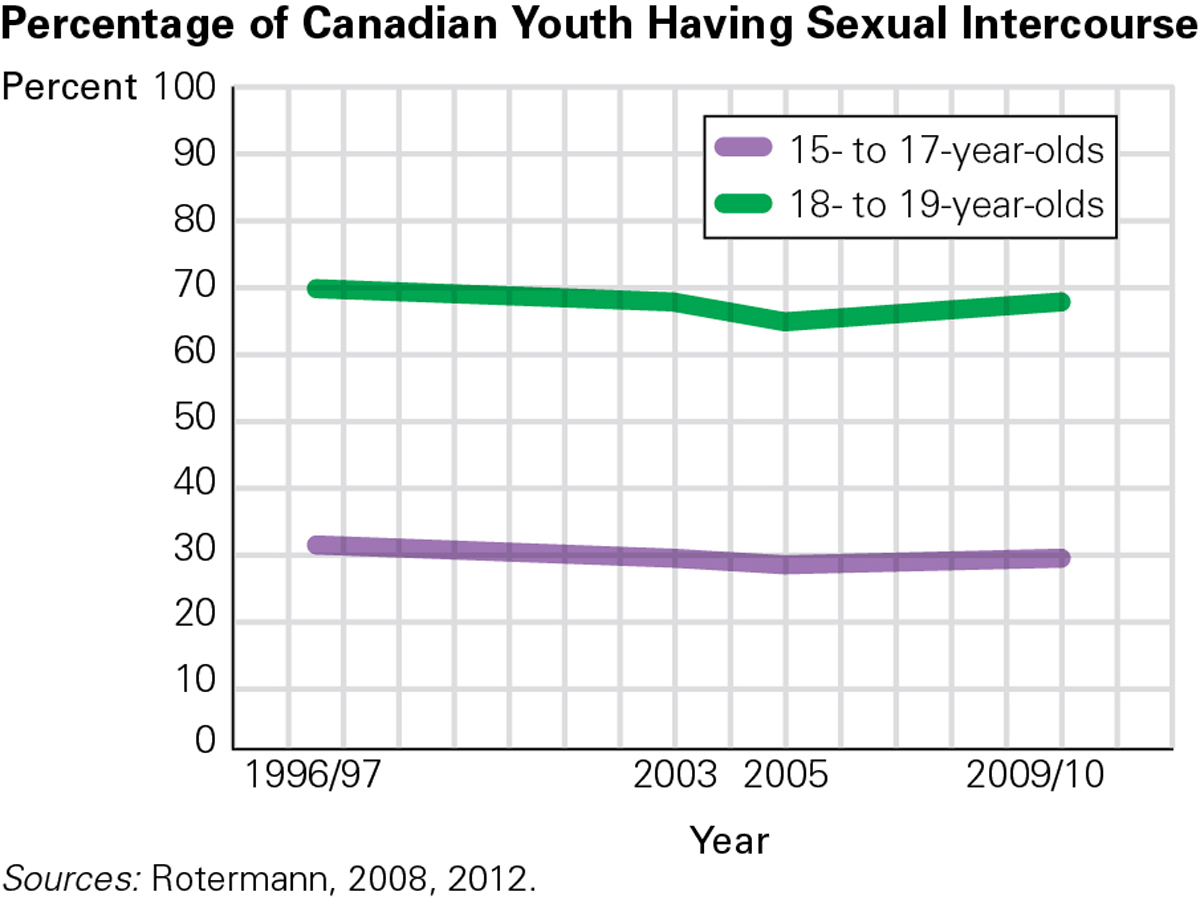

For all these, cohort is crucial. For most of the twentieth century, North American youth reported sexual activity at younger and younger ages. For the most part, this trend has either reversed or stabilized. In Canada, the percentage of 15-

During the same period, the double standard (with boys expected to be more sexually active than girls) decreased, and today boys and girls are quite similar in reported sexual activity. Both sexes are much more knowledgeable about sexual matters, which may be the underlying reason for all the trends reported above.

372

Romance

Decades ago, Australian researcher Dexter Dunphy (1963) described the sequence of male–

- Groups of friends, exclusively one sex or the other

- A loose association of girls and boys, with public interactions within a crowd

- Small mixed-

sex groups of the advanced members of the crowd - Formation of couples, with private intimacies.

Dunphy recognized, and later data from many nations confirm, that culture affects the timing and manifestation of each step, but not the sequence. Youth worldwide (and even the young of other primates) avoid the other sex in childhood and are attracted to them after puberty, with romantic partnerships gradually forming. This universal pattern suggests that physiological maturation governs this sequence.

In modern developed nations, where puberty begins with hormones at about age 10 and enduring partnerships occur much later, each of Dunphy’s four stages typically lasts several years. Early, exclusive romances are more often a sign of social trouble than maturity, especially for girls (Eklund et al., 2010; Hipwell et al., 2010).

Romance and Sexual IntercourseContrary to adult fears, many teenage romances do not include sexual intercourse. When and with whom a person becomes sexually active depends on a cascade of factors, including age at puberty, parenting practices, peer pressure, culture, and dating relationships (Longmore et al., 2009). In British Columbia in 2008, even though one-

Regarding sex-

However, everyone is influenced by biology, hormones, society, and culture. All adolescents have sexual interests (biology), which produce behaviours that teenagers in other nations would not engage in (culture) (Moore & Rosenthal, 2006).

© ANDREAS MEICHSNER/VISUM/THE IMAGE WORKS

373

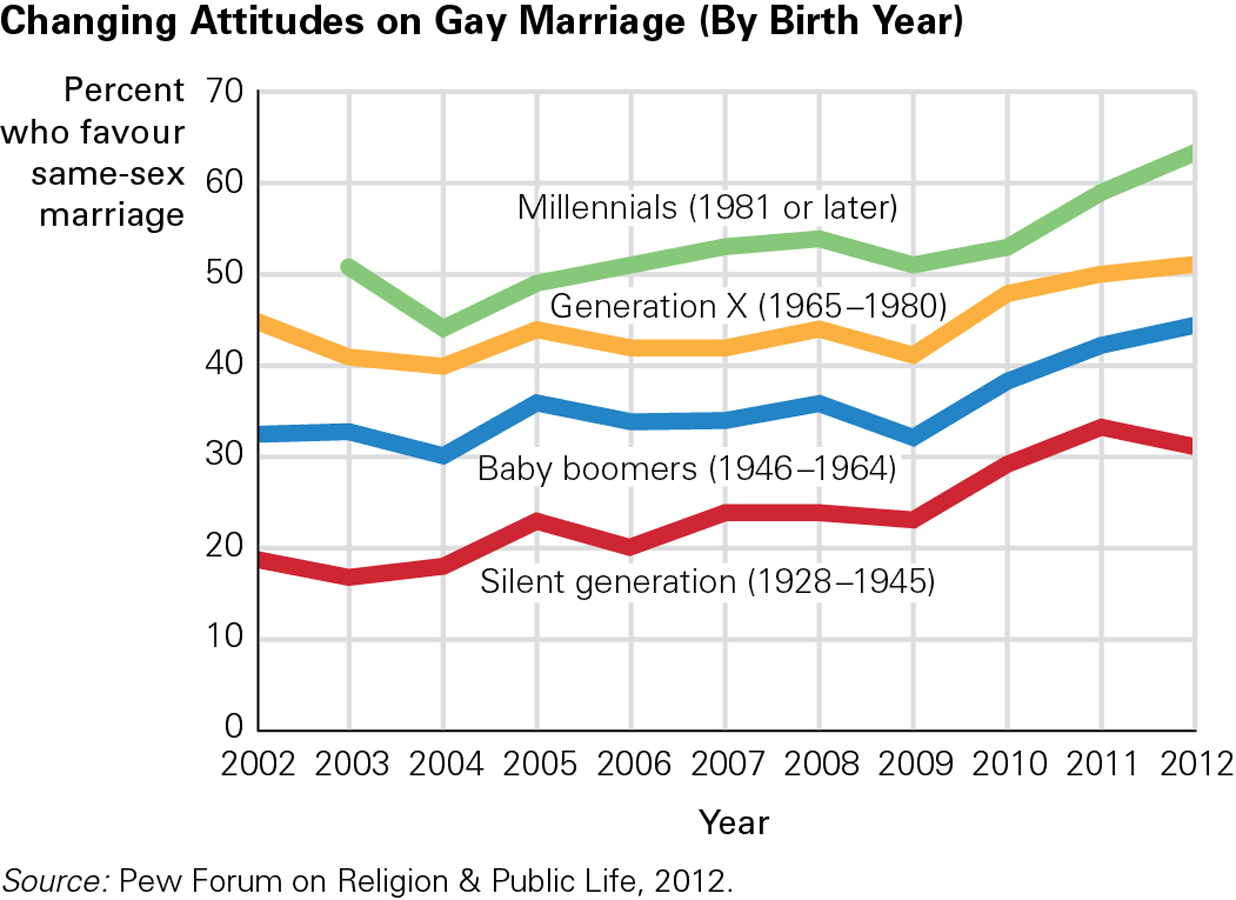

Same-

It is not known how many adolescents are romantically oriented toward people of their own sex, partly because sexual orientation can be strong, weak, acted upon, secretive, or unconscious. Relying on self-

Research in the United States indicates that boys who identify as male and girls who identify as female (no issue with gender identity), and who are attracted to people of their same sex, develop happily as long as society accepts them. However, many gay youth hide or deny their orientation by dating members of the other sex. Binge drinking, drug addiction, and suicidal thoughts are more common among this group, with bisexual youth and youth who are confused about their sexuality being particularly vulnerable (MMWR, June 10, 2011; Reiger & Savin Williams, 2012).

Possible Problems

As you read, teen births and abortions are declining worldwide. Furthermore, adolescents are more informed about sexuality than they were a few generations ago, and, at least in North America, the rate of teenage intercourse is lower in the twenty-

Adolescent PregnancyPoverty and lack of education correlate with teenage pregnancy and a host of problems for both teenage mothers and their babies (Santelli & Melnikas, 2010). These problems begin even before birth. No matter what their SES, younger pregnant teenagers are often malnourished and postpone prenatal care (Borkowski et al., 2007). If a pregnant teenager is under 16 (most are not), complications—

The risks to the mother decrease after age 16, but the children of young parents (even as “old” as 17 or 18) have more medical, educational, and social problems. From a developmental perspective, each child is born not only to the mother but also to the family. In previous generations, more family support was forthcoming. Since most teen mothers were married, most fathers were legally committed to the children of teenage mothers. Furthermore, unlike in the current job market, most such fathers could find employment. In addition, 50 years ago few grandmothers on either side of the family were in the labour force; they often helped with child care. Currently, some unmarried fathers and some employed grandmothers are committed to the children of teenage mothers, but on average family support is much less available than it once was.

374

Sexual AbuseChild sexual abuse is defined as any activity (including fondling and photographing) that sexually stimulates an adult and that involves a juvenile. The most common time for sexual abuse, which is often committed by family members, is when the first signs of puberty occur, with girls particularly vulnerable, although boys are also at risk.

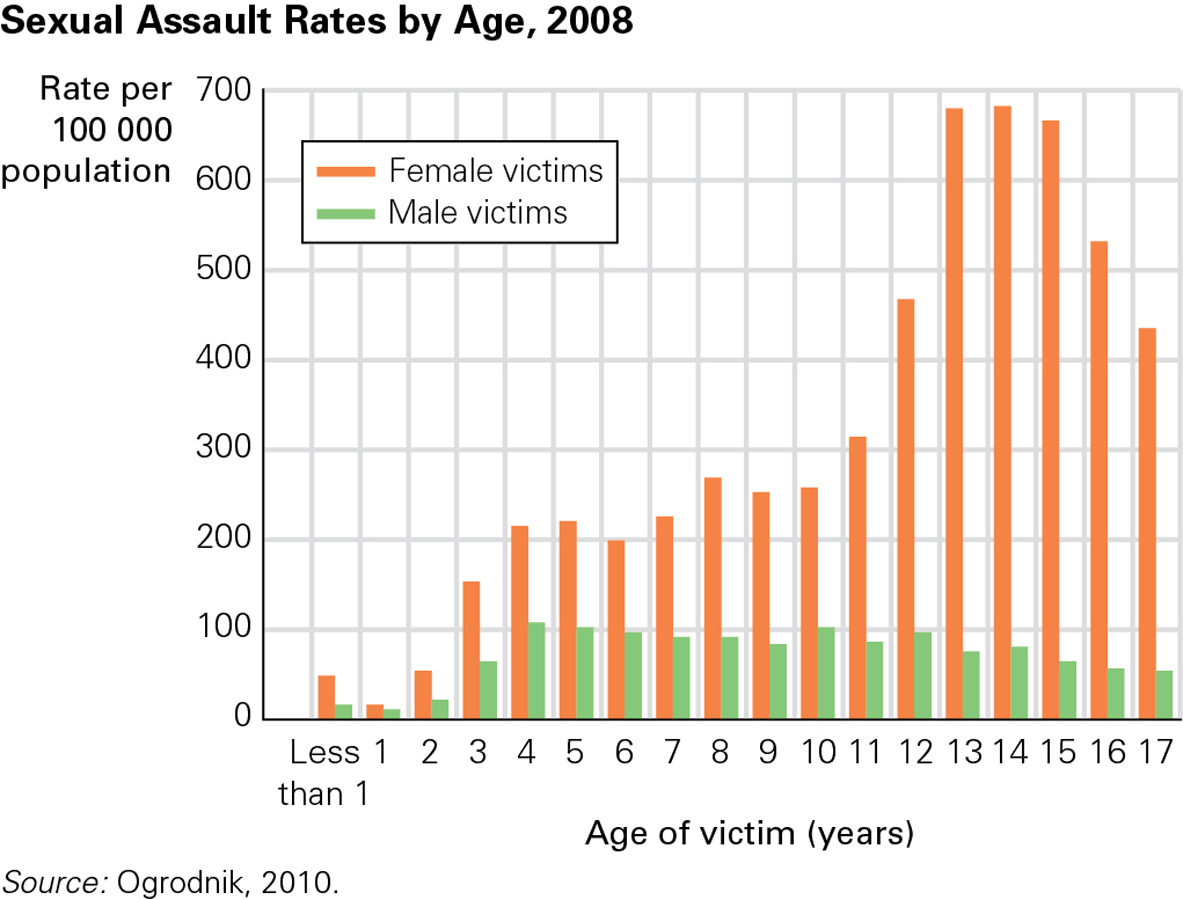

Prevalence studies find national variations in sexual assault rates. In Canada, sexual assault is the second most common type of violence committed against children that is reported to the police. While both girls and boys are vulnerable to sexual abuse, 82 percent of child sex abuse victims were female. Children ages 12 to 14 years reported the highest rates of sexual abuse. (See Figure 10.3 for Canadian abuse data.)

Relatively low child sexual abuse rates are reported from Asia, and relatively high rates are reported for girls in Australia and boys in Africa (Stoltenborgh et al., 2011). A study of the general population in England found that 2.8 percent of women and 0.8 percent of men had experienced unwanted intercourse before adulthood (Bebbington et al., 2011). International differences are affected by definitions and by the cultural willingness of adults to report past abuse (Hillberg et al., 2011). However, researchers worldwide agree that sexual abuse is not uncommon, that it is more likely than other forms of maltreatment to occur across the SES spectrum, that rates increase at puberty, and that it is equally prevalent among all ethnic groups.

Child sexual abuse is often rationalized by the abuser as relatively harmless, especially if it does not include intercourse or if a young teenager does not object. Yet research finds that the victims may be affected for many years. No matter what criteria are used, developmentalists conclude that the long-

Remember that the HPA (hypothalamus–

Other research found that girls who have been sexually abused tend to experience earlier puberty, partly because of the dysregulation of the HPA axis (Mendle et al., 2011). As you remember from Chapter 9, early puberty for girls often leads to many other problems. Another study found that childhood sexual abuse correlates, in adulthood, with difficulty recognizing and expressing emotions, yet feeling depressed overall (Thomas et al., 2011).

Many studies indicate that the emotional consequences of childhood sexual abuse—

375

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Consequences of Sexual Abuse

Puberty not only increases the odds of sexual abuse, but it can also make the emotional consequences worse because young adolescents have not yet developed a firm sense of their identity (Graber et al., 2010). For example, an 11-

The long-

Consider what you have just read about the importance of supportive family and helpful peers, and then think of how sexual abuse undercuts those connections. Typically, abuse occurs at home, is perpetrated by an adult, and is allowed to continue by people who are supposed to protect the child.

For example, two sisters, La Tanya and Tichelle, were repeatedly sexually abused by their mother’s live-

The consequences extend far beyond the event. Young people who are sexually exploited typically fear sex and devalue themselves for their remaining lifetimes. Those two girls did manage to find outside help, but even as adults they are plagued by their former abuse. For example, La Tanya has nightmares that cause her to wake up and compulsively check all the locks.

La Tanya and Tichelle are just two cases. In other instances, no long-

Remember from Chapter 1 that a single case is not conclusive. Scientific research is needed on a group of victims, ideally over several years with a control group. At least one such study has been conducted—

Sadly, after confidential interviews, 14 of those initially selected for the control group were found also to have been sexually abused, although that had not been reported to authorities. Other studies have also found that sexual abuse often goes unreported. Those participants who had not reported their abuse were excluded from the final comparison group.

Although both victims and controls moved residences frequently in adolescence and adulthood (including some who went to homeless shelters and some who moved in with distant relatives, leaving no forwarding addresses), the researchers were extraordinarily dedicated. They maintained contact with almost all the participants, keeping in touch (e.g., sending them birthday cards) even when funding temporarily stopped (Trickett et al., 2011).

Thus, because many guidelines for good longitudinal research were followed, the results of this study are probably valid—

To be specific, school achievement and language development were impaired for life. Intellectual problems were apparent throughout adolescence (often years after police action stopped the abuse). In adulthood, many former victims suffered new physical and sexual abuse, severe depression, drug addiction, and obesity.

This study also found that harm extended to the next generation. Some of the 84 women had children, who also experienced cognitive and emotional problems. Of their 78 babies, three died in infancy, and nine were permanently removed from their mothers. These rates were many times higher than those for the control group, who themselves had higher rates of child death or foster care than the national averages—

Only the most severely abused or neglected children are removed from their parents. Many others suffer while remaining with their mothers. The fact that nine of the surviving children were removed indicates that many of the other 66 children were also impaired by having mothers who had been sexually abused.

376

Infections and DiseasesTeen pregnancy, abortions, and sexual abuse are less common than they were a decade ago, perhaps because sex education is earlier and more relevant than it was. However, one major problem of teenage sex shows no signs of abating: sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Worldwide, sexually active teenagers have higher rates of the most common STIs—

STIs were earlier called sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) or venereal disease (VD), terms that referred to any infection transmitted through sexual contact. One reason for the name change is that diseases may be long-

Those who have sexual intercourse before age 16 are twice as likely to become infected as are those who begin sexual activity after age 19 (Ryan et al., 2008). One reason is biological. Fully developed women have some natural biological defences against STIs; this is less true for pubescent girls (WHO, 2005). In addition, if symptoms appear, teens are reluctant to seek diagnosis or alert their partners. Infections continue and spread as a result. In cultures or families in which teenage sex is forbidden, adolescents avoid treatment for STIs until pain requires it.

Condom use, which can protect against STIs, varies internationally. French 15-

| Country | Sexually Active (% of total) | Used Condom at Last Intercourse (% of those sexually active) |

|---|---|---|

| Canada | 23 | 78 |

| England | 29 | 83 |

| France | 20 | 84 |

| Israel | 14 | 72 |

| Russia | 33 | 75 |

| United States | 41 | 68 |

| Sources: MMWR, June 4, 2010; Nic Gabhainn et al., 2009. | ||

Psychosocial ProblemsSexual health is multi-

377

Sex Education

Many adolescents have strong sexual urges but minimal logic about pregnancy and disease. That might be expected, given the power of intuitive thought and the differential maturation of the limbic system and prefrontal cortex. They do not know what is normal and what is dangerous, and they do not think logically unless they must.

Without guidance, millions of teenagers worry that they are oversexed, under-

Learning From ParentsHome is where sex education begins. Every study finds that explicit parental communication is influential (Longmore et al., 2009). Ideally, parents are the best sex educators because they know their children well and can have private conversations that allow teens to ask personal questions. However, many parents wait too long to discuss sex, are silent about crucial aspects, and know little about their adolescents’ romances. For example, one study showed that most parents of 12-

What exactly should parents tell their children? That is the wrong question, according to a longitudinal study of thousands of adolescents. A more relevant question might be “How exactly should parents talk to their children?” The study showed that teenagers tended to ignore parental lectures, for instance, in which they were warned to stay away from sex. Adolescents were more likely to remain virgins if they had a warm relationship with their parents—

Learning From PeersAdolescent sexual behaviour is strongly influenced by peers, especially when parents are silent, forbidding, or vague. Many younger adolescents discuss details of romance and sex with other members of their clique, seeking advice and approval (Laursen & Mooney, 2007).

Often the boys brag and the girls worry. Sometimes two inexperienced partners teach each other. However, the lessons from a sexual partner are more about pleasure and techniques than about consequences and protection. Only about half of U.S. adolescent couples discuss how they will avoid pregnancy and disease before they have sex (Ryan et al., 2007).

Learning From the MediaAnother source of sex information is the media. Sexual content appears almost seven times per hour on the TV shows most watched by teenagers (Steinberg & Monahan, 2011). That content is almost always enticing: Almost never does a television character develop an STI, deal with an unwanted pregnancy, or mention (much less use) a condom. Print media that teenagers read is no better. One study found that men’s magazines convince teenage boys that manliness means many sexual conquests (Ward et al., 2011).

The impact of exposure to sex on TV, in film, and in music is controversial (Collins et al., 2011; Steinberg & Monahan, 2011). Although there is a correlation between adolescent exposure to media sex and adolescent sexual initiation, that correlation may reflect selection, not cause. Perhaps teenagers watch sexy TV because they are sexually active, not vice versa. One analysis concludes that “the most important influences on adolescents’ sexual behavior may be closer to home than Hollywood” (Steinberg & Monahan, 2011).

378

ESPECIALLY FOR Sex Educators Suppose adults in your community never talk to their children about sex or puberty. Is that a mistake?

Ideally, parents should talk to their children about sex, presenting honest information and listening to the child’s concerns. However, many parents find it very difficult to do this because they feel embarrassed.

Learning at SchoolMost northern European nations begin sex education in elementary school, and by middle school students learn about sexual responsibility, masturbation, same-

Many North American sex educators wish teachers would be more forthcoming about sex. However, probably the entire culture, not just the curriculum, is relevant. Within Canada, the curriculum for sex education varies from province to province. At present, Quebec is the only province that does not have mandatory sex education in school, although it has recently moved to reinstate mandatory sex education classes (Feldman, 2011). In the other provinces, changes to the curriculum are highly controversial. For example, Ontario has the oldest sex education curriculum in the country, introduced in 1998. A planned revision to the curriculum for Grades 1 to 8 was cancelled by the provincial government in 2010 after religious groups complained that it would introduce children to concepts, such as masturbation and same-

The reality is that in the Internet age, many children and teens go online to learn about sex, often viewing pornography, which may not be the best way to develop a comprehensive knowledge and healthy attitudes about this realm of human experience. One commentator noted:

In the fifth grade, my friends and I had a special afternoon tradition. When school let out at 3:30, we would walk to Katherine’s house (a pseudonym), raid her fridge, go upstairs to her bedroom, lock the door and watch Internet pornography. Where were Katherine’s parents? They were at work. But it wouldn’t have mattered. When they were around, we just turned off the sound, or read erotic literature on a website called Kristen Archives. This is how we gained the indispensable knowledge that some women like to be ravished by farmhands, and others, by farm animals. The year was 1999. We had not yet sat through our first sexed class [in Ontario], but when we did, almost two years later, it was spectacularly disappointing. We had seen it all, and now we were shading in a diagram of the vas deferens.

[Teitel, 2013]

Online pornography presents all sorts of challenges, but one question it raises is how society will deliver to its youth an alternative way of learning about sex, and about the joys, the dangers, and the responsibilities that go with it. It remains to be seen how provincial and territorial boards of education will meet the challenges posed by the “learning experiences” teenagers can access on the Internet and social media such as Facebook, Twitter, and Flickr.

According to a controlled nationwide study of sex education in the United Kingdom, whether or not an adolescent becomes sexually active depends more on family, peers, and culture than on information from classes (Allen et al., 2007). The success of sex education is measured not by whether adolescents can learn facts (most pass multiple-

379

KEY Points

- Adolescent sexual interactions are healthier than they were a few decades ago, with fewer unwanted pregnancies, fewer abortions, and more contraception use.

- Biological impulses at puberty lead to sexual interest, but culture strongly affects behaviour, including whether a teenager becomes sexually active and with whom.

- Adolescents benefit from parental discussion of sexual matters, but many parents are unable or hesitant to talk openly and honestly about sex with their children.

- Sex education varies dramatically from nation to nation, and in Canada, from one province or territory to another.