10.4 Emotions: Sadness and Anger

Adolescence is usually a wonderful time, perhaps better for current teenagers than for any prior generation. Nonetheless, troubles plague about 20 percent of today’s adolescents. Distinguishing between normal moodiness and serious pathology is complex. Adolescent emotions change day to day, even minute by minute. For a few, negative emotions become intense, chronic, or even deadly.

Depression

The general trend from late childhood through adolescence is toward less confidence, with more moments of emotional despair and anger than earlier—

On average, self-

Adolescents of any background with low self-

One of the first major surveys on depression in children in Canada was conducted by the Ontario Child Health Study on youths aged 6 to 16 in the late 1980s. Findings indicated that depression rates ranged by age from 2.7 to 7.8 percent. More recently, based on Statistics Canada’s Canadian Community Health Survey—

380

Clinical DepressionSome adolescents sink into clinical depression, a feeling of a deep sadness and hopelessness that disrupts all normal, regular activities. The origins and causes, such as alleles and early care, predate adolescence. Then puberty—

It is not known whether the reasons for these gender differences are primarily biological, psychological, or social (Alloy & Abramson, 2007). Obviously, sex hormones differ, but girls also experience social pressures from their families, peers, and cultures that boys do not. Perhaps the combination of biological and psychosocial stresses causes some to slide into depression.

Genes also play a factor. For instance, adolescent girls are especially likely to be depressed if their mothers are belligerent, disapproving, and contemptuous. However, some girls seem genetically protected. They have equally difficult mothers, but they escape depression, probably because they are innately less vulnerable (Whittle et al., 2011).

One study found that the short allele of the serotonin transporter promoter gene (5-

A cognitive explanation has been offered for gender differences in depression. Rumination—talking about, remembering, and mentally replaying past experiences—

Adolescent depression is expressed in many ways, including eating disorders, school alienation, and sexual risk taking, all already discussed. In addition, an increasing number of depressed adolescents turn to self-

SuicideSerious depression can lead to thoughts about killing oneself (called suicidal ideation). Suicidal ideation can in turn lead to parasuicide, also called attempted suicide or failed suicide. It includes any deliberate self-

381

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among Canadian teenagers, next to accidents. In 2009, almost one-

Youths from low-

ESPECIALLY FOR Journalists You just heard that a teenage girl jumped off a tall building and died. How should you report the story?

Since teenagers seek admiration from their peers, be careful not to glorify the victim’s life or death. Facts are needed, as is, perhaps, the inclusion of warning signs that were missed or cautions about alcohol abuse. Avoid prominent headlines or anything that might encourage another teenager to do the same thing.

Many people mistakenly think suicide is more frequent in adolescence for four reasons:

- The rate, low as it is, is far higher than it appeared to be decades ago.

- Statistics on “youth” often include emerging adults, aged 18 to 25, whose suicide rates are higher than those of adolescents.

- Adolescent suicides capture media attention, and people of all ages make a logical error (called base rate neglect), noticing the published cases and not considering the millions of non-

suicidal youth. - Parasuicide may be more common in adolescence than later.

Because they are more emotional than analytical, adolescents are particularly affected when they hear about a suicide, either via media reports or from peers (Insel & Gould, 2008). That makes them susceptible to cluster suicides, a term for several suicides within a group over a brief span of time—

Delinquency and Disobedience

Like low self-

Externalizing actions are obvious. Many adolescents slam doors, defy parents, and complain to friends about parents or teachers. Some teenagers—

Before further discussing juvenile rebellion, we should emphasize that adolescents who commit serious crimes are unusual. Most teenagers usually obey the law, with moments of hot anger (loud profanity) or minor rebellion (smoking a joint), but nothing more. Dozens of longitudinal studies confirm that increased anger after puberty is normal, but anger is usually expressed in acceptable ways. For a few, anger explodes: Teens break something or hurt someone. And a few of that few have been aggressive throughout childhood, becoming worse after puberty.

382

Breaking the LawBoth the prevalence (how widespread) and the incidence (how frequent) of crime increase during adolescence and continue at high levels in emerging adulthood. Arrest statistics in every nation reflect this, although some nations have much higher arrest rates overall than others.

In Canada in 2006, 180 000 youth were implicated with violating the Criminal Code, which does not include traffic tickets. The rate was 6885 per 100 000, an increase of 3 percent over the previous year. However, 60 percent of these youths were not formally charged (Taylor-

| Most serious offence | 2010/2011 |

|---|---|

| Total admissions of most serious offence | 43 344 |

| Total violent offences | 9 560 |

| Assault level 2 | 2 335 |

| Common assault | 2 395 |

| Sexual assault | 439 |

| Robbery | 2 512 |

| Other violent offences | 1 909 |

| Total property offences | 8 002 |

| Break and enter | 2 712 |

| Theft $5000 and under | 2 099 |

| Theft over $5000 | 442 |

| Possession stolen goods | 978 |

| Mischief | 1 264 |

| Other property offences | 507 |

| Other criminal code | 5 084 |

| Total other offences | 3 300 |

| Drug- |

1 052 |

| Youth Criminal Justice Act (VJCA) and Young Offenders Act (YOA) | 2 007 |

| Other federal offences | 6 |

| Provincial and Municipal offences | 235 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, 2012k. | |

Causes of DelinquencyTwo clusters of factors, one from childhood (primarily brain-

The first of these clusters includes a short attention span, hyperactivity, inadequate emotional regulation, slow language development, low intelligence, early and severe malnutrition, autistic tendencies, maternal cigarette smoking, and being the victim of severe child abuse, especially if it includes blows to the head. Most of these factors are more common among boys than girls, which may be one reason why females account for only about 5 percent of the inmates in Canadian correctional facilities.

Any of these signs of neurological impairment (either inborn or caused by early experiences) increases the risk that a child will become a life-course-persistent offender (Moffitt et al., 2001). As the term implies, a life-

The second cluster of factors that predict delinquency encompasses risk factors that are primarily psychosocial. They include having deviant friends; having few connections to school; living in a crowded, violent, unstable neighbourhood; not having a job; using drugs and alcohol; and having close relatives (especially older siblings) in jail. These factors are more prevalent among low-

The criminal records of both types of teenagers may be similar. However, if adolescence-

ESPECIALLY FOR Police Officers You see some 15-

Avoid both extremes: Don’t let them think this situation is either harmless or horrifying. You might call their parents and discuss the situation.

383

By contrast, life-

One way to prevent adolescent crime is to analyze earlier behaviour patterns and stop delinquency before the police become involved. Three pathways can be seen:

- Stubbornness can lead to defiance, which can lead to running away—

runaways are often victims as well as criminals (e.g., prostitutes, petty thieves). - Shoplifting can lead to arson and burglary.

- Bullying can lead to assault, rape, and murder.

Each of these pathways demands a different response. The rebelliousness of the stubborn child can be channelled or limited until more maturation and less impulsive anger prevail. Those on the second pathway require stronger human relationships and moral education.

Those on the third pathway present the most serious problem. Bullies need to be stopped and helped in early childhood, as already discussed. If that does not occur, and a teenager is still a bully, intense treatment may deflect the pattern. If that does not occur, and a teenager is convicted of assault, rape, or murder, then arrest, conviction, and jail might be the only options. In all cases, intervention is more effective earlier than later (Loeber & Burke, 2011).

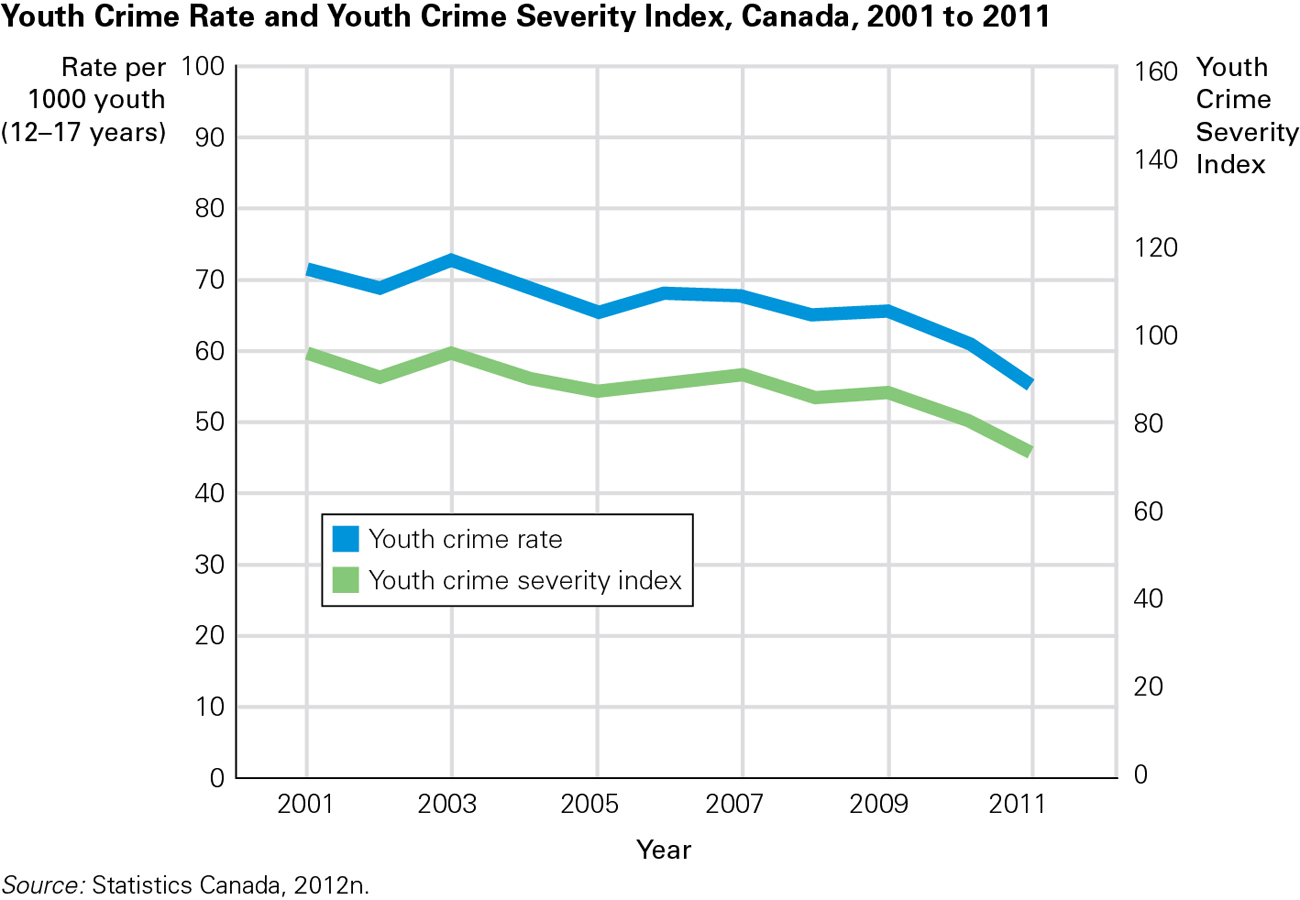

As you can see in Figure 10.4, both the crime rate and crime severity for Canadian youths ages 12 to 17 years decreased steadily over the 10-

384

KEY Points

- The emotions of adolescents often include marked depression and anger, sometimes pathological, sometimes not.

- Clinical depression is more common in teenage girls than boys; experts disagree as to whether this is primarily caused by hormones, rumination, or society.

- Breaking the law is common among adolescents, with more arrests during these years than later.

- Some offenders are adolescence-

limited— they stop breaking the law at adulthood; some are life- course- persistent— they become criminal adults.