11.2 Cognitive Development

As you remember, each of the four periods of child and adolescent development is characterized by major cognitive advances, each described by Piaget. Piaget believed that the fourth stage, formal operational thought, continued throughout life. However, some recent scholars contend that adult thought differs from adolescent thinking: It is more practical, more flexible, and better able to coordinate objective and subjective perspectives. This may constitute a major advance, combining a new ordering of formal operations with a necessary subjectivity (Sinnott, 1998).

Postformal Thought

Many developmentalists believe that Piaget’s fourth stage, formal operational thought, is inadequate to describe adult cognition. Some have proposed a fifth stage, called postformal thought, characterized by “problem finding,” not just “problem solving.” At this stage a person is more open to ideas and less concerned with absolute right and wrong (Yan & Arlin, 1995).

As a group of scholars explained, in postformal thought “one can conceive of multiple logics, choices, or perceptions…in order to better understand the complexities and inherent biases in ‘truth’” (Griffin et al., 2009). That is more typical of adult thought than adolescent thought; hence the idea that a fifth stage exists.

ESPECIALLY FOR Someone Who Has to Make an Important Decision Which is better: to go with your gut feelings or to consider pros and cons as objectively as you can?

Both are necessary. Mature thinking requires a combination of emotions and logic. Take your time (don’t just act on your first impulse) and talk with people you trust. Ultimately, you will have to live with your decision, so do not ignore either intuitive or logical thought.

Combining Emotions and LogicAs you read in Chapter 9, adolescents use two modes of thought (dual processing, called by various names). They use formal analysis to learn science, distill principles, develop arguments, and resolve the world’s problems; in the other mode, they think spontaneously and emotionally. However, they rarely coordinate both types of thinking and prefer the quick, impulsive, intuitive thought.

Postformal thinkers are less impulsive than adolescents. They do not wait for someone to present a problem to solve or for circumstances to require a reaction. They take a more flexible and comprehensive approach, using forethought, noting difficulties, and anticipating problems, not denying, avoiding, or procrastinating. As a result, postformal thought is more practical as well as more creative and imaginative than thinking in previous cognitive stages (Wu & Chiou, 2008).

402

Really a Stage?Piaget’s notion that the final, and best, thinking is formal operational, achieved at adolescence, has come under especially heavy criticism, with some data finding that adults do not usually reach formal operations. As mentioned, others argue that formal operational thought does not adequately capture the level of adult cognition. Similarly, problems arise with postformal thought. Attempts to measure it empirically are not very successful: Many other variables in addition to intellectual maturation affect how adults think (Cartwright et al., 2009).

Some cognitive scientists, especially those who take an information-

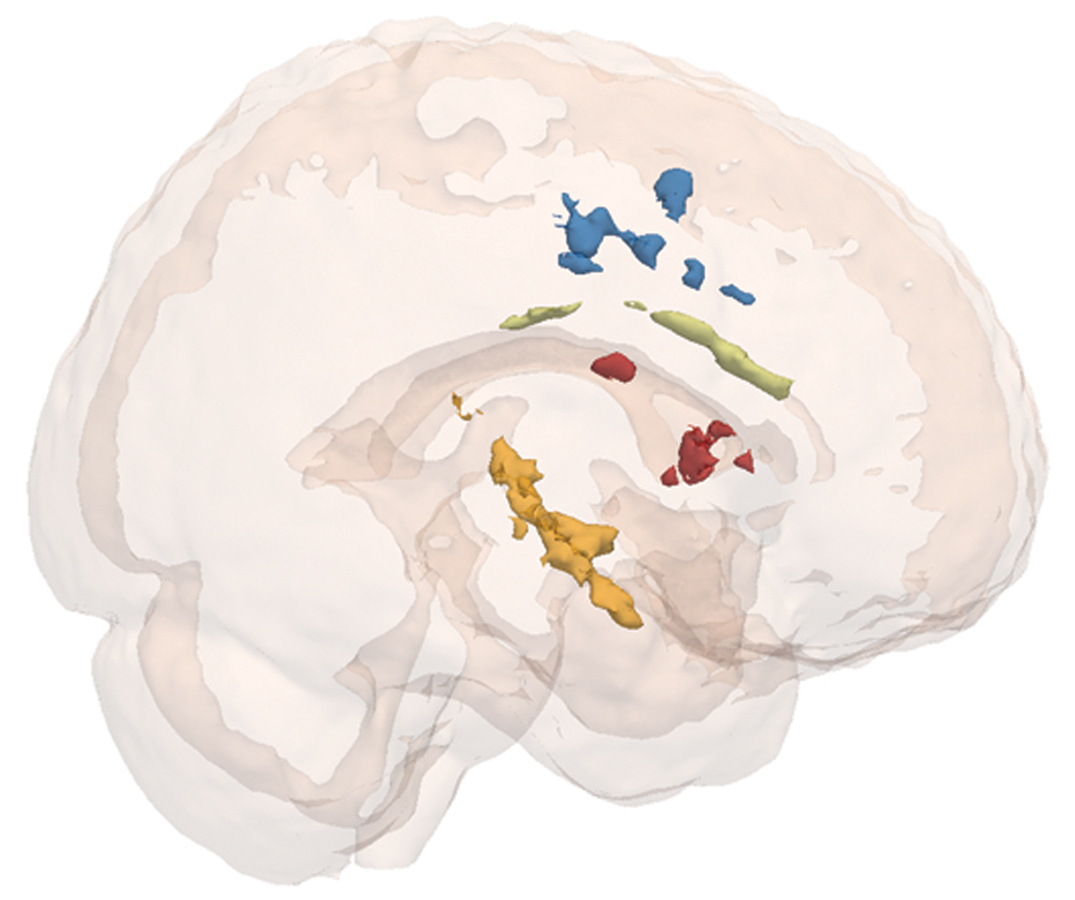

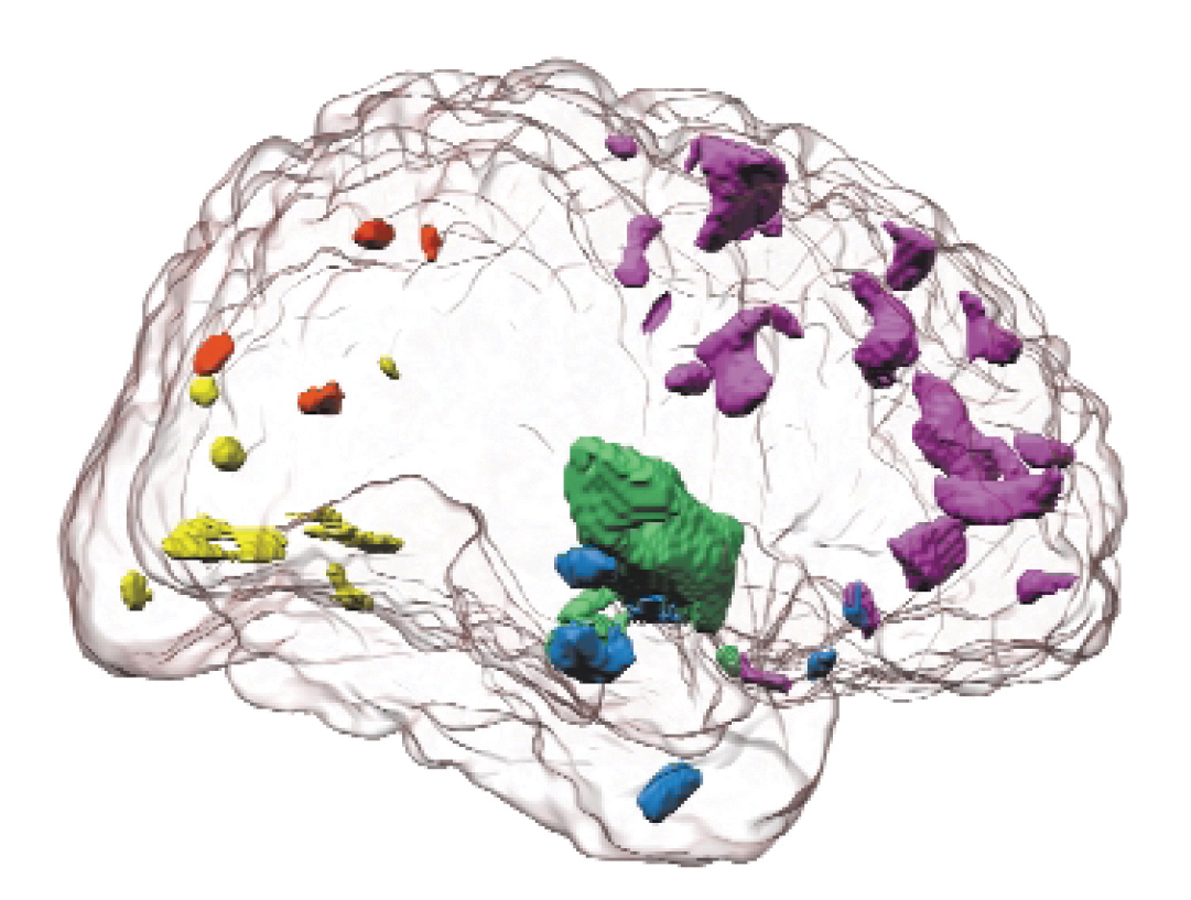

Nonetheless, the prefrontal cortex is not fully mature until the early 20s, and new dendrites and even new neurons grow throughout adulthood. This neurological maturation enables adults to think in ways that adolescents do not. One lead researcher concludes that adult thinking can be ordered in terms of increasing levels of complexity and integration (Labouvie-

That same study found that social understanding continued to advance beyond early adulthood (Demetriou & Bakracevic, 2009). Social understanding includes knowing how best to interact with other people: making and keeping good friends, responding to social slights, helping others effectively, and so on. It makes sense that social cognition continues to improve, since cohort changes, cultural variations, and genetic uniqueness combine to make this the most complex type of thought.

403

Another study found that college students who have friends from other backgrounds are more likely to think in postformal ways (Galupo et al., 2010). The researchers believe that having friends with varied cultural perspectives advances postformal thought. A third study found that students’ concepts of God became more complex theologically when they were more capable of postformal thinking (Benovenli et al., 2011).

Overall, many scholars find that thinking changes both qualitatively and quantitatively during adulthood (Bosworth & Hertzog, 2009). The term fifth stage may be a misnomer, but emerging adults can, and often do, reach a new cognitive level when their brains and life circumstances allow it.

Countering Stereotypes

Most North Americans say that they are not prejudiced, and their behaviour reveals no bias—

A notable example of implicit prejudice, and then the ability to overcome it, occurs with stereotype threat, first named by an African-

Stereotype threat may interfere with emerging adults in many ways. For instance, if young people fear that leaving home will expose them to prejudice, they might not live in residence at college or university. That will limit their exposure to other opinions. Perhaps the most widely known example of stereotype threat is reduced performance by students on tests if they think that others expect them to do poorly. This finding has been replicated in laboratory studies, in real classrooms, and during standardized tests.

Stereotype threat does not only have negative effects on individuals but also can boost performance, in a stereotype boost. Shih and his colleagues (1999) reported that Asian-

404

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Undercutting Stereotype Threat

One statistic has troubled social scientists for decades: African-

Claude Steele, the African-

Hundreds of studies show that almost all humans can be harmed by stereotype threat: Women underperform in math, older people are more forgetful, bilingual students stumble while speaking English, and every member of a stigmatized minority in every nation performs less well if they think others are judging them unfairly.

Margaret Walsh and her colleagues from Memorial University in Newfoundland explored the influence of gender labelling (i.e., identifying whether a character was female, male, or gender neutral) and gender stereotype threat in mathematical problem solving among males and females (1999). For example, the problem-

In another experiment, students wrote a version of the Standardized Achievement Test (SAT) that had been modified in terms of both gender labelling and gender stereotype threat. Gender labelling modifications to the questions did not account for gender differences in achievement. However, female students scored lower when they believed that the test had previously shown gender differences. There was no difference in achievement when women were told that the test was comparing Canadian and American students (Walsh et al., 1999).

Even those sometimes thought to be on top—

Can stereotype threat be eliminated, or at least reduced? One group of researchers developed a hypothesis that stereotype threat will decrease and academic achievement will increase for African-

The hypothesis: Convincing college students that intellectual ability could be improved by hard work (the incremental, not the entity, theory of intelligence described in Chapter 9) would encourage them to study and prevent choking under pressure (as when taking exams). The intervention succeeded for the African-

This experiment has intrigued thousands of researchers. They realized that this study required replication, since the participants were only 79 students at a highly selective university. Might other stereotyped groups respond differently?

Soon this study was replicated with many other groups, often but not always targeting young adults. The results confirm, again and again, that stereotype threat is pervasive and debilitating, but that it can be alleviated (Inzlicht & Schmader, 2012; Mangels et al., 2012; Rydell & Boucher, 2010). It is activated especially when someone reminds a person of the stereotype (e.g., “This test will reveal whether women are inferior in math ability”), but it disappears if a person internalizes the notion that the stereotype is irrelevant (e.g., “My math ability depends only on me and is not affected by gender”).

405

The Effects of College or University

A major reason that emerging adulthood has become a new period of development, when people postpone the usual markers of adult life (marriage, a steady job), is that many older adolescents seek education, choosing to postpone traditional adult responsibilities.

MassificationTertiary (or post-

ESPECIALLY FOR Those Considering Studying Abroad Given the effects of college and university, would it be better for a student to study abroad in the first year or last year of post-

Since one result of college or university is that students become more open to other perspectives while developing their commitment to their own values, foreign study might be most beneficial after several years of post-secondary education. If they study abroad too early, some students might be either too narrowly patriotic (they are not yet open) or too quick to reject everything about their national heritage (they have not yet developed their own commitments).

As mentioned above, university or college graduates are also healthier, living about 10 years longer than those without a high school diploma. An Organisation for Economic Co-

To improve health and increase productivity, every nation has increased the number of students enrolled in college and university. This has led to massification, the idea that tertiary education could benefit everyone (the masses) (Altbach et al., 2010). The United States was the first major nation to accept that idea, establishing thousands of institutions of higher learning and boasting millions of college students by the middle of the twentieth century. The United States no longer leads in massification, however. More than half of all 25-

Massification has expanded in Asia and Africa, where university and college enrolment has more than tripled in the past several decades (Altbach et al., 2010). Thirty years ago, many wealthy and capable students in developing nations travelled to the West to earn university and college degrees. Such students often returned to their home nations as professors, bringing new perspectives to their classrooms. A global shift is under way: Hundreds of new universities have opened in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. Many undergraduates now remain in their own nations to continue their studies. As a result, there are far more university students in China and in India than in North America. Of course, the total population of those nations is larger than that of North America, but these numbers are part of a global trend.

406

Post-

According to one classic study (Perry, 1981, 1999), thinking progresses through nine levels of complexity over the four years that lead to a bachelor’s degree. A first-

| First- |

Position 1 | Authorities know, and if we work hard, read every word, and learn right answers, all will be well. |

| Dualism modified | Transition | But what about those others I hear about? And different opinions? And uncertainties? Some of our own authorities disagree with each other or don’t seem to know, and some give us problems instead of answers. |

| Position 2 | True authorities must be right; the others are frauds. We remain right. Others must be different and wrong. Good authorities give us problems so we can learn to find the right answer by our own independent thought. | |

| Transition | But even good authorities admit they don’t know all the answers yet! | |

| Position 3 | Then some uncertainties and different opinions are real and legitimate temporarily, even for authorities. They’re working on them to get to the truth. | |

| Transition | But there are so many things they don’t know the answers to! And they won’t for a long time. | |

| Relativism discovered | Position 4a | Where authorities don’t know the right answers, everyone has a right to his or her own opinion; no one is wrong! |

| Transition | Then what right have they to grade us? About what? | |

| Position 4b | In certain courses, authorities are not asking for the right answer. They want us to think about things in a certain way, supporting opinion with data. That’s what they grade us on. | |

| Position 5 | Then all thinking must be like this, even for them. Everything is relative but not equally valid. You have to understand how each context works. Theories are not truth but metaphors to interpret data with. You have to think about your thinking. | |

| Transition | But if everything is relative, am I relative, too? How can I know I’m making the right choice? | |

| Position 6 | I see I’m going to have to make my own decisions in an uncertain world with no one to tell me I’m right. | |

| Transition | I’m lost if I don’t. When I decide on my career (or marriage or values), everything will straighten out. | |

| Commitments in relativism developed | Position 7 | Well, I’ve made my first commitment! |

| Transition | Why didn’t that settle everything? | |

| Position 8 | I’ve made several commitments. I’ve got to balance them— |

|

| Transition | Things are getting contradictory. I can’t make logical sense out of life’s dilemmas. | |

| Graduating Students | Position 9 | This is how life will be. I must be wholehearted while tentative, fight for my values yet respect others, believe my deepest values are right yet be ready to learn. I see that I shall be retracing this whole journey over and over— |

| Sources: Perry, 1981, 1999. | ||

407

Which aspect of college or university is the primary catalyst for such growth? Is it the challenging academic work, the professors’ lectures, the peer discussions, the new setting, or living away from home? All are possibilities. Perry found that the college or university experience itself causes this progression, as peers, professors, books, and class discussion stimulate new thoughts. Every scientist finds that social interaction and intellectual challenge advance thinking.

College and university students expect classes and conversations to further their intellectual depth—

Professors may also advance in their own thinking as they teach and learn, passing those advances on to their students. For example, one of the leading thinkers in postformal thought is Jan Sinnott, a professor and former editor of the Journal of Adult Development. She describes the first course she taught:

I did not think in a postformal way…. Teaching was good for passing information from the informed to the uninformed…. I decided to create a course in the psychology of aging…with a fellow graduate student. Being compulsive graduate students had paid off in our careers so far, so my colleague and I continued on that path. Articles and books and photocopies began to take over my house. And having found all this information, we seem to have unconsciously sworn to use all of it….

Each class day, my colleague and I would arrive with reams of notes and articles and lecture, lecture, lecture. Rapidly!… The discussion of death and dying came close to the end of the term (naturally). As I gave my usual jam-

[Sinnott, 2008]

Sinnott changed her lesson plan. In the next class, the student told her story.

In the end, the students agreed that this was a class when they…synthesized material and analyzed research and theory critically.

[Sinnott, 2008]

Sinnott still lectures and gives multiple-

Current ContextsYou may have noticed that Perry’s study was first published in 1981. Hundreds of other studies have also found that a college or university education deepens cognition, but most of that research also occurred in the twentieth century. Since cohort and culture are crucial, you may wonder if those conclusions still hold.

An impressive twenty-

408

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

What Is the Purpose of Post-

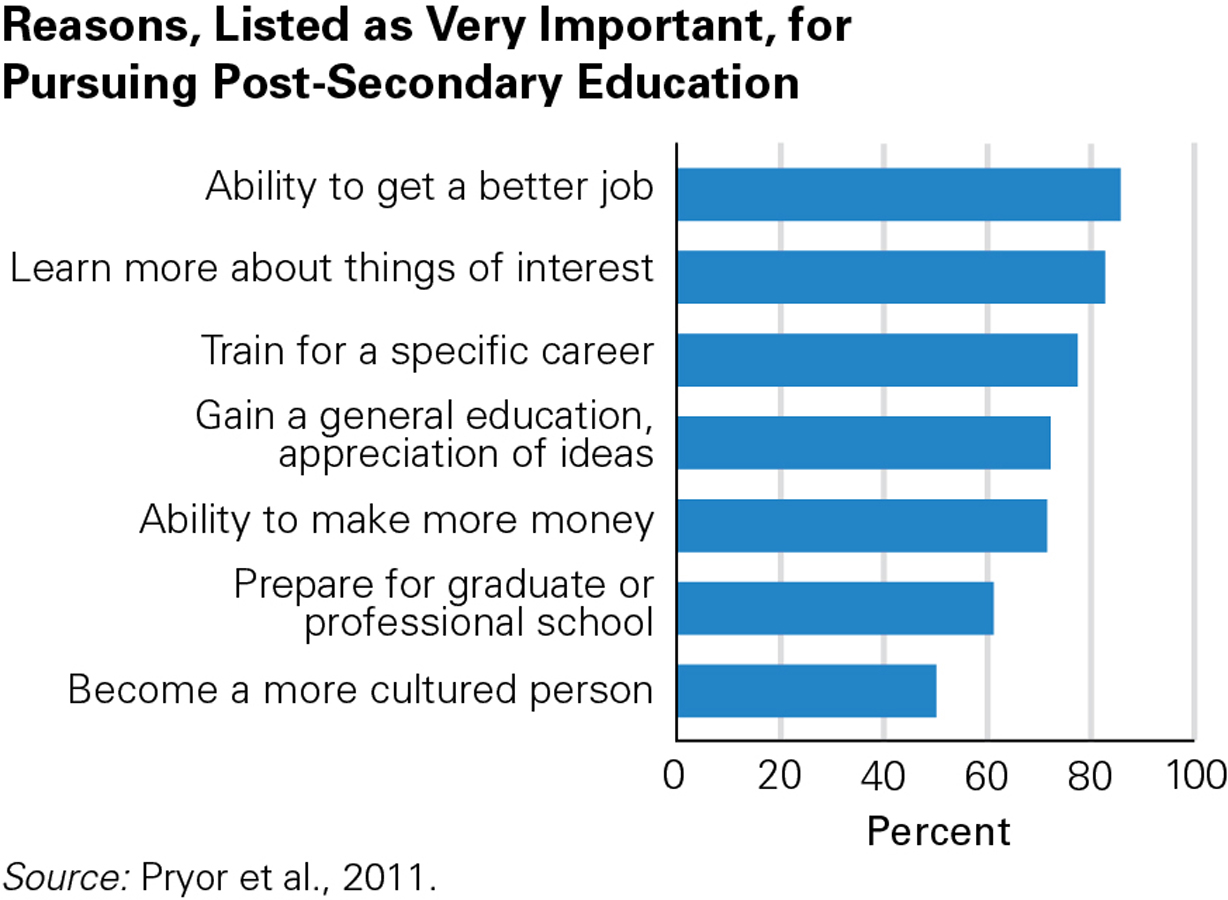

Underlying the debate about standards and massification are opposite opinions about the purpose of higher education. Developmentalists, most professors, and many college and university graduates believe that personal and intellectual growth is the goal. However, others believe that acquiring specific skills and knowledge is more important. Many contemporary students seem to agree (see Figure 11.3).

In 2011/2012,1 144 812 Canadian students were enrolled in university and 664 733 in college (Statistics Canada, 20121). In 2011, 245 235 Canadian university students and 179 226 Canadian college students graduated (Statistics Canada, 2012m). Despite rising tuition fees, the proportion of Canadians aged 25 to 64 receiving a post-

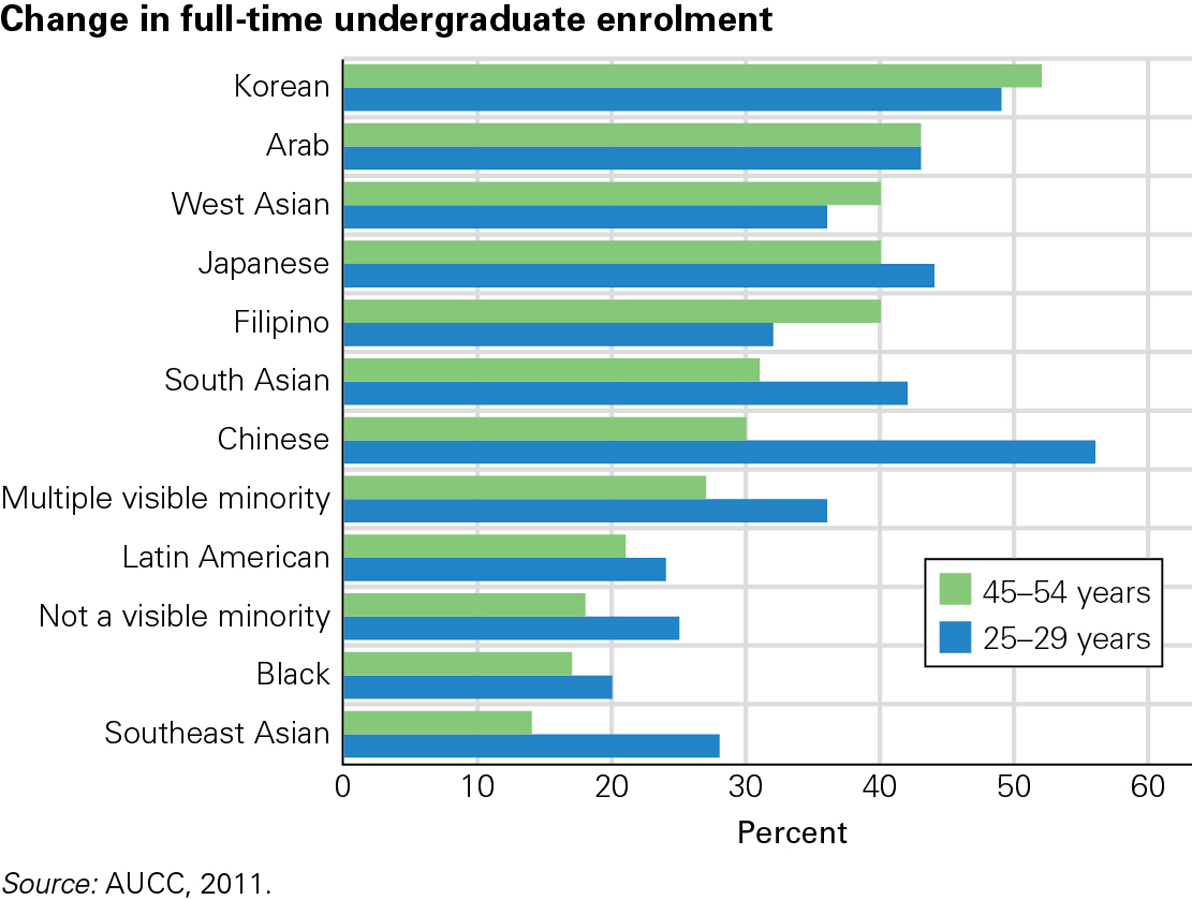

Notably, although university enrolment has been steadily increasing over the years for most Canadians, for one segment of the population the increase has been much less. The Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada (AUCC) reports that the proportion of Aboriginal Canadians with a university degree is significantly lower than non-

AUCC (2011) reports that the increased number of students in higher education is a result of Canada’s demand for a highly skilled and educated labour force—

Employers often want workers with advanced skills, specific knowledge, and practical experience with technology. Canadian colleges and universities have responded to these demands by modifying and creating new programs that meet the needs of the community and students. Universities have also enhanced their quality of education by integrating more interactive and engaging learning experiences, and more and more colleges and universities are collaborating to provide dual degree and certificate programs. These changes have been shown to increase students’ academic performance, knowledge acquisition, and skills development (AUCC, 2011).

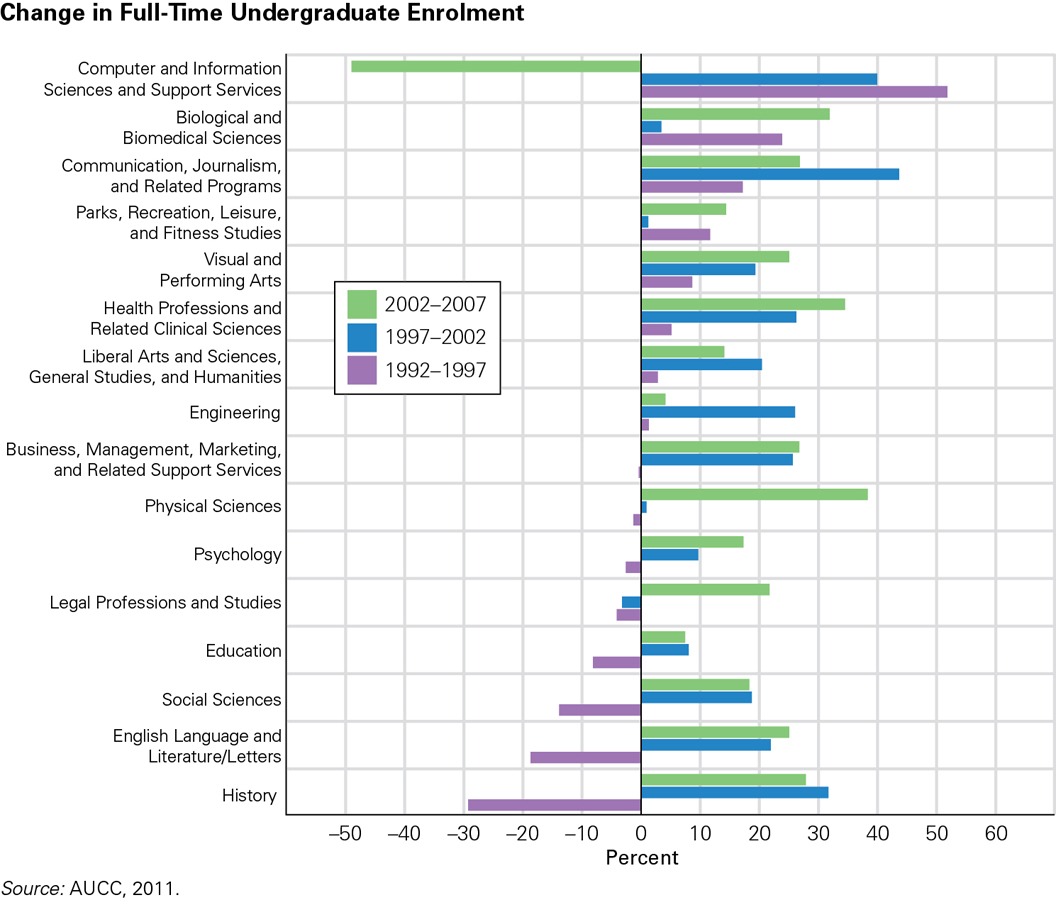

Changes have also been seen in students’ fields of study. In the early 1990s, enrolment shifted from arts and science majors to various professional and science-

Opposing views of the purpose of college and university are evident between present-

SUSTC does not require prospective students to take the national exam (Gao Kao); instead, creativity and a passion for learning are the admission criteria (Stone, 2011). SUSTC faculty are supposed to nurture curiosity and evoke questions, not lecture. After waiting a year to see how the first group of students performed, the Chinese government accredited SUSTC in April 2012 (Huang, 2012).

409

Besides gaining employment, college and university graduates have higher income advantages, are less likely to face long periods of low income, and are less likely to experience labour disruptions. If they do face labour disruptions, the length of time is shorter than those with no degree. Graduates also help their co-

As compared to high school graduates, students in and completing college and university are also more likely to have healthier and longer lives and to smoke and abuse drugs and alcohol less. They are more socially active in volunteering, more engaged in social and political activities, and more likely to share and promote educational, health, and social values to their children and their children’s children (AUCC, 2011).

The question remains: Is the purpose of post-

The Effects of DiversityAt least one characteristic of the twenty-

ESPECIALLY FOR High School Teachers One of your brightest students doesn’t want to go to college or university. She would rather keep serving in a restaurant, where she makes good money in tips. What do you say?

Even more than ability, motivation is crucial for post-secondary success, so don’t insist that she attend college or university immediately. Since your student has money and a steady job (prime goals for today’s college- or university-bound youth), she may not realize what she would be missing. Ask her what she hopes for, in work and lifestyle, in the decades ahead.

The most obvious increased diversity is gender: In 1970, two-

410

Ethnic, economic, religious, and cultural diversity are also evident. Although in Canada and the United States the modal students are mostly still European-

Discussion among people of different backgrounds, ages, and experiences leads to intellectual challenge and deeper thought. Thus, the increased diversity of the student body may enhance learning (Bowman, 2011; Loes et al., 2012). Colleges and universities that make use of their diversity—

Attending university or college does not automatically produce a leap ahead in cognitive development or in appreciation of differing political, social, and religious views. Skeptical readers might question the data that link university and college graduation to wealthier, wiser, and happier adults. Such skepticism is warranted since correlation does not equal causation: Student characteristics before college or university may be a third variable that explains these links.

However, when selection is taken into account, college and university attendance still seems to aid cognitive development (Pascarella, 2005). Even the critics agree that some students at every institution advance markedly in critical thinking and analysis because of their post-

KEY Points

- Adult cognition has been described as postformal, a fifth stage, although not every scholar agrees with that description.

- As the prefrontal cortex matures, thinking in adulthood becomes more flexible, and better able to combine emotions and analysis.

- College and university attendance is rapidly increasing in developing nations, as it is apparent that tertiary education improves health, productivity, and income.

- College and university education advances thought, not only through academic work, but also via the diversity of the student body.