11.3 Psychosocial Development

A theme of human development is that continuity and change are evident throughout a lifetime. In emerging adulthood, the legacy of early development is apparent amidst new achievement. As you remember, Erikson recognized this ongoing process in describing the fifth of his eight stages, identity versus role confusion. The identity crisis begins in adolescence, but it is not usually resolved then.

411

Identity Achieved

Erikson believed that the outcome of earlier crises provides the foundation for each new stage. He associated each stage with a particular virtue and type of psychopathology, as shown in TABLE 11.2. He also thought that earlier crises could re-

| Stage | Virtue/Pathology | Possible in Emerging Adulthood If Not Successfully Resolved |

|---|---|---|

| Trust vs. mistrust | Hope/withdrawal | Suspicious of others, making close relationships difficult |

| Autonomy vs. shame and doubt | Will/compulsion | Obsessively driven, single- |

| Initiative vs. guilt | Purpose/inhibition | Fearful, regretful (e.g., very homesick in college or university) |

| Industry vs. inferiority | Competence/inertia | Self- |

| Identity vs. role diffusion | Fidelity/repudiation | Uncertain and negative about values, lifestyle, friendships |

| Intimacy vs. isolation | Love/exclusivity | Anxious about close relationships, jealous, lonely |

| Generativity vs. stagnation | Care/rejection | [In the future] Fear of failure |

| Integrity vs. despair | Wisdom/disdain | [In the future] No “mindfulness,” no life plan |

| Source: Enkson, 1982. | ||

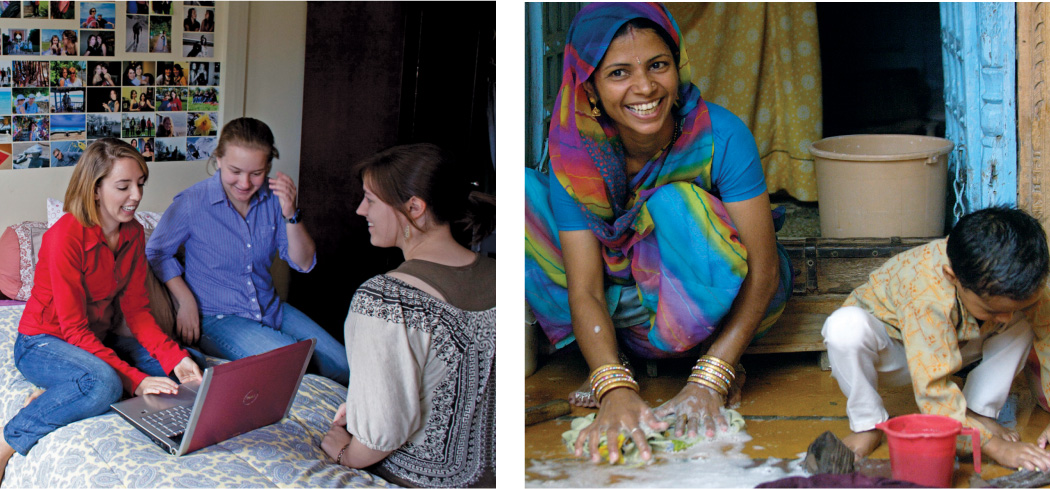

Worldwide, adults ponder all five arenas of identity—

Ethnic IdentityIdentity development, especially the development of ethnic and racial identity, now continues long past adolescence (Whitbourne et al., 2009). This extended search is often the result of new challenges that emerging adults face.

The most basic challenge is how to identify oneself amidst a multi-

Whether one’s heritage is mixed or not or considered minority or not, ethnicity is a significant aspect of a person’s identity (Phinney, 2006). During late adolescence and early adulthood, people are more likely to be proud, or at least accepting, of their ethnic background than younger adolescents are (Worrell, 2008).

More than any other age group, as they leave their childhood homes to enrol in colleges or universities or to find work, emerging adults have friends and acquaintances of many backgrounds. Typically, they have both positive and negative experiences related to their ethnic background, developing a strong sense of ethnic identity—

It may be a mistake if emerging adults either assimilate (accepting the host culture, rejecting their native heritage) or become alienated (isolated and antagonistic). Those who resist both assimilation and alienation fare best: They are most likely to maintain their ethnic identity, deflect stereotype threat, and become good students (Rivas-

412

University or college classes, especially in history, ethnic studies, and sociology, attract many emerging adults who want to learn more about their culture. In addition, extracurricular groups help solidify identity because students encounter others of similar backgrounds who confront the same issues, as well as youth of other backgrounds as they join teams, political committees, special interest groups, and so on.

Vocational IdentityEstablishing a vocational identity is considered part of growing up, not only by developmental psychologists, but also by emerging adults themselves (Arnett, 2004). As already noted, many young adults go to college or university to prepare for work. Emerging adulthood is a critical time for the acquisition of resources—

Preparation for lifetime work may include taking temporary jobs. Between ages 18 and 27, the average U.S. worker holds eight jobs, with college-

OBSERVATION QUIZ

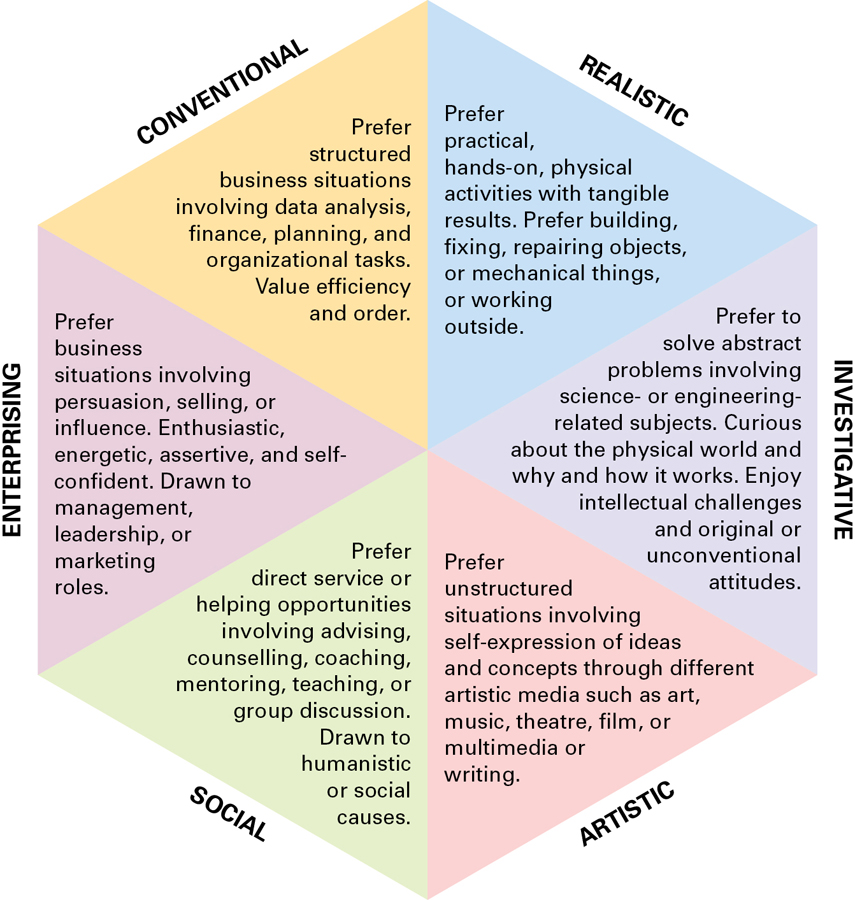

Based on Holland’s diagram in Figure 11.6, which category do you best fit in? Is this category consistent with your major/area of study?

The category that you fit in will depend on how you define your identity. This will include taking future job opportunities, interests, skills, and experience into account.

None of this is guaranteed to make vocational choice easy. For most emerging adults, “the process of identifying with society’s work ethic, the core of this issue [identity achievement] in Erikson’s scheme, continues to evolve throughout early adulthood” (Whitbourne et al., 2009). The young worker is not yet climbing, rung-

413

Many developmentalists wonder whether achieving a single vocational identity is still possible and desirable. Especially for young people, hiring and firing sometimes seems disconnected from education, skills, or aspirations. Commitment to a particular career may limit rather than increase vocational success.

Flexibility seems especially needed for the current generation. Sébastien LaRochelle-

- being employed in temporary jobs (part-

time or full- time) (56 percent) - working in a permanent job but in a part-

time capacity (26 percent) - being unemployed, out of the labour force, and not attending school (19 percent).

Recent recessions have affected a disproportionate number of younger workers in terms of job loss. In 2012, the unemployment rate of youths aged 15 to 24 was 14.3 percent compared with a rate of 6 percent for workers aged 25 to 54 and for those 55 and older (Bernard, 2013).

Personality in Emerging Adulthood

Continuity and change are evident in personality as well as identity (McAdams & Olson, 2010). Of course, the genetic roots of temperament and the early childhood influences on personality endure. If self-

Yet personality is not static. After adolescence, new characteristics may appear and negative traits diminish. Emerging adults make choices that break with the past. This age period is now characterized by years of freedom from a settled lifestyle, which allows shifts in attitude and personality.

A crucial factor found in many studies is whether the person thrives in high school and college or university. This is affected by personality, but also affects personality (Klimstra et al., 2012). In other words, college or university success can improve personality.

REUTERS/SHANNON STAPLETON

414

Increasing HappinessPsychological research finds both continuity and improvement in attitudes. For example, one longitudinal study found that 17-

This positive trend of increasing happiness has become more evident over recent decades, perhaps because young adults are more likely to make their own life decisions (Twenge et al., 2008). Logically, one might expect that the many stresses and transitions of emerging adulthood would reduce self-

Worrisome Children Grow UpThe research just cited about rising self-

By early adulthood, those early traits were still evident, but neither was as extreme nor debilitating as earlier. Continuity could be seen, especially for those who had been aggressive 4-

Yet, unexpectedly, these aggressive emerging adults had as many friends as their average peers did. They sought more education and rated themselves as quite conscientious. Their arrests were usually adolescent-

A closer examination of their school records found that behaviour, not ability, caused their childhood teachers to fail them. That proved harmful; many had to repeat grades. In high school, they were older than their classmates, often rebelled against restrictions and assumptions, and ultimately quit. But they still enjoyed learning and were intellectually capable.

That explained some seemingly surprising outcomes: As emerging adults, most of the formerly aggressive children were developing well, with social and vocational lives that were normal for their cohort. Many had put their childhood problems behind them; some were employed and others had enrolled in college or university.

As for those formerly shy 4-

415

Serious Psychological DisordersThe general trends toward better health and rising self-

The most troubling increase is in schizophrenia, rare before the mid-

A combination of medical and psychological interventions can reduce the impairment, but consequences of the disorder may remain throughout life. Those who are not diagnosed with schizophrenia but who have schizoid symptoms—

Severe anxiety and depression are not unusual during adolescence and emerging adulthood, especially for young women. The anxiety that is particularly likely to be diagnosed at about age 20 is social phobia, the fear of other people. Without treatment, anxiety and depression restrict an emerging adult’s later development, as they make it much more difficult to succeed in college or university or to find a mate.

Many believe that ongoing psychological vulnerability, combined with the need to establish one’s own identity apart from the family, is the reason why many mental illnesses become more pronounced in adolescence and emerging adulthood (O’Neil et al., 2011), though there are certainly biological causes as well (Trudeau et al., 2012). Family communication and guidelines during adolescence can reduce the rate of these internalizing disorders. As a result of their more positive mental health, individuals will be less likely to drop out of school and more likely to have higher attainment levels, which in turn can lead to higher income. On the other hand, mental illness is linked to an increased risk of certain physical health problems, such as chronic respiratory conditions and heart disease (Canadian Mental Health Association (Ontario), 2009; Himelhoch et al., 2004; McIntyre et al., 2006).

It is important to acknowledge that mental health and mental illness are not the opposite of each other; when mental health increases, mental illness does not necessarily decrease (Keyes, 2007). Instead, individuals who believe they have a purpose in life, good relations with others, experience personal growth, feel a sense of belonging, and can contribute to society have positive mental health. This will provide individuals with meaningful and productive lives, regardless of whether they have mental illness or mental health problems (Keyes, 2007; Pape & Galipeault, 2002).

PlasticityIn the research just discussed as well as in other research, plasticity is evident. Personality is not fixed by age 5, or 15, or 20, as it was once thought to be. Emerging adults are open to experiences (a reflection of their adventuresome spirit), which allows personality shifts and eagerness for more education (McAdams & Olson, 2010; Tanner et al., 2009). The trend is toward less depression and more joy, along with more insight into the self (Galambos et al., 2006; McAdams et al., 2006).

Going to college or university, leaving home, paying one’s way, stopping drug abuse, moving to a new city, finding satisfying work and performing it well, making new friends, committing to a partner—

416

Total transformation does not occur since genes, childhood experiences, and family circumstances affect people all their lives. Nor do new experiences always result in desirable changes. Cohort may be important: Perhaps rising self-

Increased well-

Intimacy

In Erikson’s theory, after achieving identity, people experience the sixth developmental crisis, intimacy versus isolation. This crisis arises from the powerful desire to share one’s personal life with someone else. Without intimacy, adults are lonely and isolated. Erikson explains:

The young adult, emerging from the search for and the insistence on identity, is eager and willing to fuse his identity with others. He is ready for intimacy, that is, the capacity to commit himself to concrete affiliations and partnerships and to develop the ethical strength to abide by such commitments, even though they call for significant sacrifices and compromises.

[Erikson, 1963,p. 263]

The urge for social connection is a powerful human impulse, one reason our species has thrived. Other theorists use different words (affiliation, affection, interdependence, communion, belonging, bonding, love) for the same human need.

There is no doubt that all adults seek friends, lovers, companions, and partners. Having close friends in early adulthood correlates with close relationships earlier in life and helps in other aspects of current life—

All intimate relationships (friendship, family ties, and romance) have much in common—

face the fear of ego loss in situations which call for self-

[Erikson, 1963]

According to a more recent theory, an important aspect of close human connections is “self-

Contemporary emerging adults often gain friends as they transition from their childhood family and move away from their neighbourhood to their adult community. This leads to wider social networks and expanded understanding, one reason for the adult cognition explained earlier. Intimacy needs remain; the way they are satisfied differs. A specific example is the use of social networking, texting, email, video chatting, and so on. Although older adults once thought that technology would lead to social isolation, the opposite seems more likely: Most emerging adults connect often with many friends, face to face and online. The result is emotional health and well-

417

Romantic PartnersLove, romance, and commitment are all of primary importance for emerging adults, although many specifics have changed. One dramatic change in Canada is that most people in their 20s are not married: The proportion of adults who are single, as well as the average age of marriage, have been rising for the past 30 years. For women in Canada, the average age at first marriage has increased from 22.5 years in 1972 to 29.1 years in 2008. For Canadian men over the same period, the average age went up from 24.9 years to 31.1 years (Employment and Social Development Canada, n.d.[c]). Most emerging adults are postponing, not abandoning, marriage.

Observers note two new sexual interaction patterns. One is “hooking up” (when two people have sex without any interpersonal relationship), and the other is “friends with benefits” (when two people are friends, sometimes having sex, but not in a dating relationship). Sometimes casual sex is a step toward a more serious relationship. As one U.S. sociologist explains, “despite the culture of divorce, Americans remain optimistic about, and even eager to enter, marriages” (Hill, 2007).

The relationship between love and marriage is obviously not only a personal one. It reflects era and culture, with three distinct patterns evident (Georgas et al., 2006):

- In about one-

third of the world’s families, love does not bring about marriage; parents do. They arrange marriages that will join two families together. - In another one-

third of families, adolescents meet only a select group, for example, people of the same ethnicity, religion, or social class. If they decide to marry someone from that pre- selected group, the man asks the woman’s father for “her hand in marriage.” For these couples, parents supervise premarital interactions, usually bestowing their blessing. That was a traditional pattern: If parents did not approve, young people parted sorrowfully or eloped. - The final pattern is relatively new, although it is the dominant one in developed nations today. Young people socialize with hundreds of other young people, mostly unknown to their parents. They sometimes hook up, they sometimes develop serious relationships, but they often do not marry until they are able, financially and emotionally, to be independent.

Suggesting “one-

Parents are peripheral for the last one-

For Western emerging adults, love is considered a prerequisite for marriage. Once love has led to commitment, sexual exclusiveness is expected. A survey asked 14 121 adults of many ethnic groups and sexual orientations to rate (on a scale from 1 to 10, 10 being the highest) how important money, race, commitment, love, and faithfulness were for a successful marriage or a serious long-

418

This survey was conducted in North America, but emerging adults worldwide now share similar values. For instance, emerging adults in Kenya also reported that love was the prime reason for sex and marriage; money was less important (S. Clark et al., 2010). The international question is whether love precedes marriage, as most Westerners believe, or follows it, as was expected in the past.

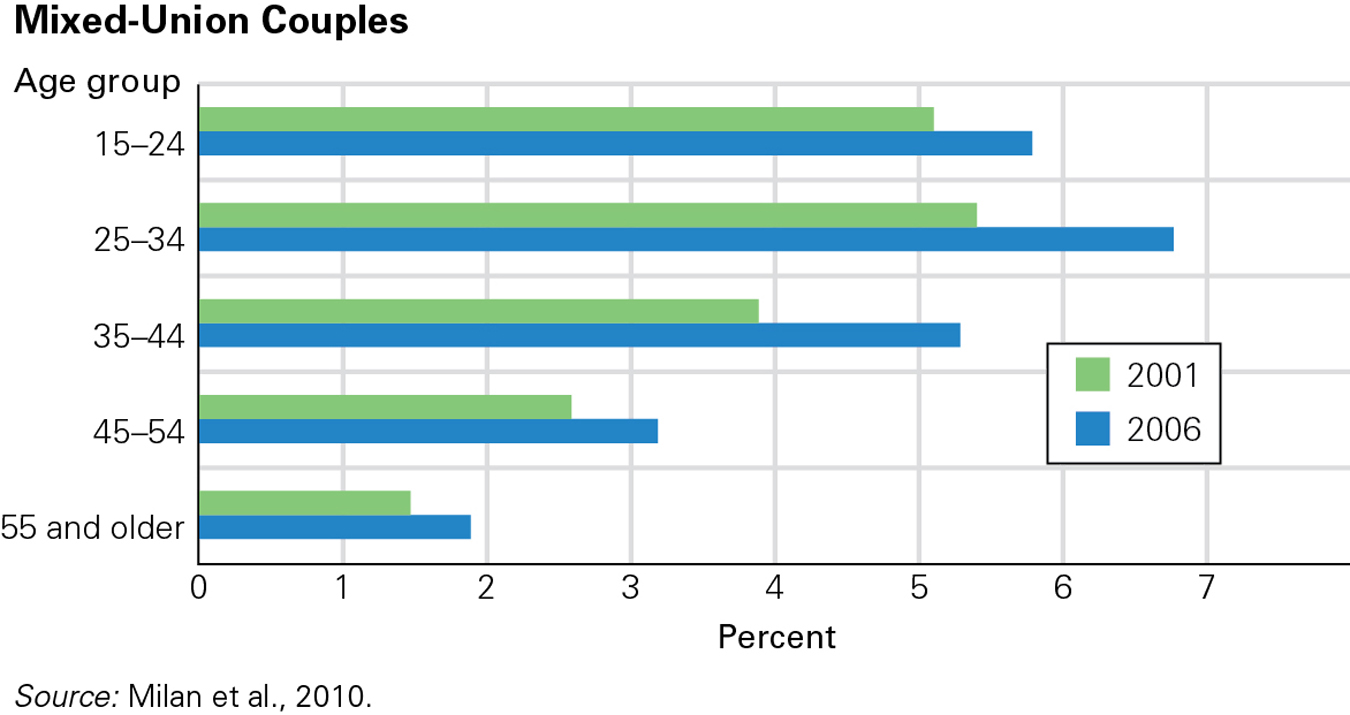

Love and EthnicityIn 2006, 3.9 percent of all married and common-

As you can see in Figure 11.7, mixed-

When it comes to romance, ethnicity may be a bond. The reasons for romances within groups involve not rejection of other groups so much as bonding with co-

Thus, emerging adults usually choose mates like themselves. That is particularly true for South Asians and Chinese living in Canada (Milan et al., 2010). These two groups are the largest visible minority groups in Canada. As a result, these populations may have a higher likelihood of meeting with and interacting with people within the same group.

Finding Each OtherAs already explained, the traditional way to find marriage partners was through the parents, or within a very narrow social circle. But many of today’s emerging adults range far from home and would resist any parental matchmaking. Instead, they must find partners among many thousands of possible mates—

Many websites now allow people to post their photos and personal information on the Internet, sharing the details of their daily lives and romantic involvement with thousands of others. This seems to be a wonderful innovation, as “the potential to reach out to nearly 2 billion other people offers several opportunities to the relationship-

419

One potential problem with this is choice overload, when too many options are available. Choice overload increases doubts after a selection is made (people wonder if another choice would have been better). Some people, feeling overloaded, freeze; they are unable to choose (Iyengar & Lepper, 2000; Reutskaja & Hogarth, 2009). Having many complex options, such as partner selection, each requiring assessment of future advantages and disadvantages, makes choice overload likely (Scheibehenne et al., 2010). Successful matches require face-

It is logical that too many choices make marriage commitment difficult, but choice overload studies have not focused scientifically on mate selection. Instead, research has compared having a few choices or many when choosing jams, or cars, or apartments. It is possible that similar doubts might emerge if a person has too many possible mates, but more research needs to be done.

We already know one problem is that having too many choices slows down analysis. If people feel rushed, they are more likely to regret their choice later on (Inbar et al., 2011). This might be why couples slow down the selection process by postponing marriage and living together instead.

Living TogetherA new form of mating for contemporary emerging adults is cohabitation, living together in a romantic partnership without being married. Marked national differences are apparent in acceptance and timing of cohabitation.

Currently, most emerging adults in Canada, the United States, northern Europe, England, and Australia live unmarried with a partner for at least a few months. Some think of their living together as a prelude to marriage, others as a test of compatibility, and still others as a way to have an intimate relationship while saving money. By contrast, in some regions—

420

In Canada in 2006, common-

The popularity of common-

[Milan et al, 2007]

| Countries | Percentage of all couples | Reference year |

|---|---|---|

| Quebec | 34.6 | 2006 |

| Sweden | 25.4 | 2005 |

| Finland | 23.9 | 2006 |

| New Zealand | 23.7 | 2006 |

| Denmark | 22.2 | 2007 |

| Iceland | 19.9 | 2006 |

| Canada | 18.4 | 2006 |

| United Kingdom | 15.5 | 2004 |

| Australia | 14.8 | 2006 |

| Ireland | 14.1 | 2006 |

| Other provinces and territories | 13.4 | 2006 |

| Source: Milan et al., 2007. | ||

Research from 27 nations finds that acceptance of cohabitation within the nation affects the happiness of those who cohabit. Within those 27 nations, among the married and cohabitants, demographic differences (such as education, income, age, and religion) affect happiness, as one might expect, but it is remarkable that national attitudes permeate such a personal experience (Lee & Ono, 2012).

Although there are practical reasons for cohabitation—

Family Forces

It is hard to overestimate the importance of the family at any period of the life span. Although made up of individuals, a family is much more than the individuals who belong to it. In dynamic synergy, children grow, adults find support, and everyone is part of a family ethos that gives meaning to, and provides models for, hope and action.

421

Linked LivesEmerging adults are said to set out on their own, leaving their parents and childhood home behind. They strive for independence and postpone establishing new family commitments. From that one might conclude that they no longer need family support and guidance. However, this would be incorrect.

The data show that parents continue to be crucial for adult children—

All members of each family have linked lives, meaning that the experiences and needs of individuals at one stage of life are affected by those at other stages (Macmillan & Copher, 2005). We have seen this in earlier chapters: Each newborn affects every family member of every age, and growing children are affected by their parents’ relationship, even if the children are not directly involved in domestic disputes, financial stresses, parental alliances, and so on.

A strong linkage between emerging adults and their parents in the twenty-

Extensive research also confirms that family patterns persist, affecting every adult as well as every child. For example, early attachment between infant and caregiver influences that child’s future relationships, including friendships, romantic partnerships, and parenthood. Securely attached infants are more likely to become happily married adults; avoidant infants hesitate to marry. Some insecure infants marry early, but they are more likely to divorce. In addition, adults who were securely attached infants are more likely to have secure relationships with their own children. Of course, plasticity is evident throughout life; early attachment affects adult relationships, but it does not determine them.

National DifferencesIs living with parents as an emerging adult the key to strong relationships? Apparently, it depends on the economy and on the culture. Almost all unmarried young adults in Italy and Japan remain in their childhood home, and in those nations both generations seem content with that arrangement. Half of the young adults in England live with their parents, but friction often arises (Manzi et al., 2006).

ESPECIALLY FOR Family Therapists Emerging-

Remember that family function is more important than family structure. Sharing a home can work out well if contentious issues—like sexual privacy, money, and household chores—are clarified before resentments arise. Encourage emerging adults and their parents to explore assumptions and guidelines.

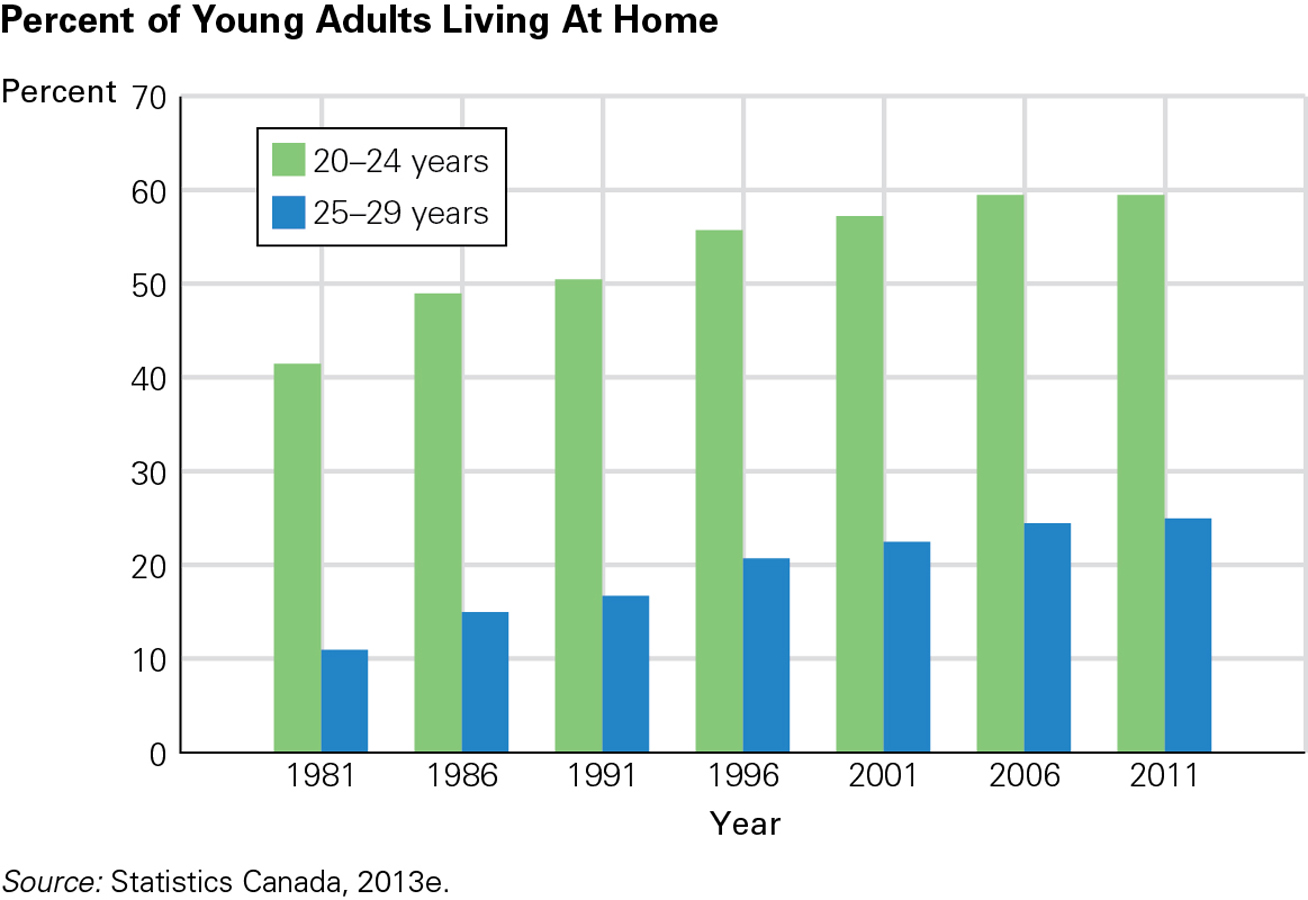

According to a recent Statistics Canada analysis of 2011 census data, 42.3 percent of Canadians aged 20 to 29 were living in their parents’ home, either because they had never moved out or because they had returned home. Adult children who move out of their parents’ home and then move back are referred to as boomerang children. There were some differences in those 20-

422

Young adults live at home for various reasons, but primarily for financial or emotional support. This does not mean that the young people are the only ones to benefit from such an arrangement, since they often contribute in various ways to the household economy and the family’s sense of well-

Some North Americans believe that dependence on parents is not healthy for young adults. However, not all North Americans agree. As explained earlier, familism is a strong value among many cultures. Closer relationships between parents and their adult children are increasingly common and welcomed among North Americans of all ethnicities. As two experts in human development write, “with delays in marriage, more Americans choosing to remain single, and with high divorce rates, a tie to a parent may be the most important bond in a young adult’s life” (Fingerman & Furstenberg, 2012).

In order for relationships to stay strong, it is important that emerging adults and their parents share the same assumptions and guidelines. What those assumptions are often depends on culture. What is expected in, say, Cambodia, would be unacceptable in, say, Colombia. Chinese young adults expect their parents and friends to comment on their romantic partners; North American adults know they must not do so. Compared with their North American contemporaries, Chinese emerging adults are about twice as likely to stop dating someone if their parents disapprove (Zhang & Kline, 2009).

Cultural differences aside, parents encourage young adults in every nation to do well in school and to get good jobs, partly to make their families proud, partly so they will be able to care for their relatives when necessary, partly to help secure their own future, and partly so they can be satisfied in their own lives.

423

All Together NowWhen we look at actual lives, not the cultural ideal of independence or interdependence, all emerging adults have much in common, including close family connections and a new freedom from parental limits (Georgas et al., 2006). It is a mistake to assume that emerging adults in Western nations abandon their parents. Just the opposite: Some studies find that family relationships improve when young adults leave home (Smetana et al., 2004).

PETE OXFORD / DANITADELMONT.COM

Regarding the overall experiences of emerging adults, this stage of life has many critical opportunities, since “decisions made during the transition to adulthood have a particularly long-

KEY Points

- Many emerging adults continue their identity search, especially for vocational and ethnic identity.

- Personality shows continuity and change in emerging adulthood, with many people gradually becoming happier. Another smaller group develops serious disorders.

- Marriage is often postponed, but intimacy needs are met in other ways.

- Computer matches and cohabitation have become the norm in North America, each with obvious advantages but also troublesome disadvantages.

- Intergenerational bonds continue to be important in every culture, with many parents helping their emerging adult children, financially and emotionally.

424