15.1 Theories of Late Adulthood

Development in late adulthood may be more diverse than at any other age: Some elderly people run marathons and lead nations, whereas others can no longer walk or talk. Moreover, individuals vary within themselves in almost every measure from day to day, with some days much better than others (Krenk et al., 2012). Many social scientists try to understand the significance and origin of these variations and to describe the general course of old age.

Some theories of late adulthood have been called self theories because they focus on individuals’ perceptions of themselves and their ability to meet challenges to their identity. Other theories are called stratification theories because they describe the ways in which societies place people on a particular life path.

Self Theories

It can be said that people become more truly themselves as they grow old, an idea captured by Anna Quindlen:

It’s odd when I think of the arc of my life from child to young woman to aging adult. First I was who I was, then I didn’t know who I was, then I invented someone and became her, then I began to like what I’d invented, and finally I was what I was again. It turned out I wasn’t alone in that particular progression.

[Quindlen, 2012, ix]

531

The essential self is protected and rediscovered, despite all the changes that may occur. Self theories emphasize how people negotiate their personal challenges (Sneed & Whitbourne, 2005). Such negotiation is particularly crucial when older adults are confronted with multiple challenges like illness, retirement, and the death of loved ones.

A central idea of self theories is that each person ultimately depends on himself or herself. As one woman explained:

I actually think I value my sense of self more importantly than my family or relationships or health or wealth or wisdom. I do see myself as on my own, ultimately.…Statistics certainly show that older women are likely to end up being alone, so I really do value my own self when it comes right down to things in the end.

[quoted in J Kroger, 2007]

Studies of personality over the life span confirm the continuity of self. An individual’s high or low level on each of the Big Five personality traits (see Chapter 13) tends to remain the same, not only throughout the earlier adult years, but even when people are in their 80s (Mõttus et al., 2012).

IntegrityThe most comprehensive self theory was from Erik Erikson. His eighth and final stage of development is called integrity versus despair, a period in which older adults seek to integrate their unique experiences with their vision of community (Erikson et al., 1986). The word integrity is often used to mean honesty, but it also means a feeling of being whole, not scattered, and comfortable with oneself. (Integrity comes from the same root word as integer, a math term meaning “a whole number, not a fraction.”)

As an example of integrity, many older people express pride and contentment regarding their personal history. They are proud of their past, even when it includes events that an outsider might not consider worthy of pride—

As Erikson (1963) explains it, such self-

This tension helps advance the person toward a more complete self-

life brings many, quite realistic reasons for experiencing despair: aspects of the present that cause unremitting pain; aspects of a future that are uncertain and frightening. And, of course, there remains inescapable death, that one aspect of the future which is both wholly certain and wholly unknowable. Thus, some despair must be acknowledged and integrated as a component of old age.

[Erikson et al, 1986]

That integration of death and the self is an important accomplishment of this stage. The life review (explained in Chapter 14) and the acceptance of death (to be explained in the Epilogue) are crucial aspects of the integrity envisioned by Erikson (Zimmermann, 2012).

532

Holding on to One’s SelfMost older people consider their personalities and attitudes quite stable over their life span, even as they acknowledge the physical changes of their bodies (Fischer et al., 2008). One 103-

The need to maintain the self may explain behaviour that younger people might consider foolish. For example, many elders hate to give up driving a car because the independence that driving offers them has become an integral part of their view of self, especially for men (Davidson, 2008). Also, objects and places become more precious in late adulthood than they were earlier, as people seek a way to hold on to identity (J. Kroger, 2007; Whitmore, 2001).

The tendency to cling to familiar possessions may be problematic if it leads to compulsive hoarding. While younger relatives may complain that the accumulation of old papers, furniture, and mementos takes up space and is a fire hazard, for the elderly, compulsive hoarding can be seen as maintaining the self: Possessions become a part of self-

Similarly, many older people refuse to move from drafty and dangerous dwellings into smaller, safer apartments because abandoning familiar places means abandoning personal history. Likewise, they may avoid surgery or reject medicine because they fear anything that might distort their thinking or emotions: Their priority is self-

The need to preserve one’s self explains why many of the elderly strive to maintain childhood cultural and religious practices. For instance, grandparents may painstakingly teach a grandchild a language that is rarely used in their current community, or encourage the child to repeat rituals and prayers they themselves learned as children. In cultures that emphasize youth and novelty, the elderly worry that their old values will be lost and, thus, that they themselves will disappear from memory.

The importance of self-

The Positivity EffectAs you remember from Chapter 14, some people cope successfully with the changes of late adulthood through selective optimization with compensation. This is central to self theories. Individuals set their personal goals, assess their own abilities, and figure out how to accomplish those goals despite limitations. For some people, simply maintaining identity correlates with well-

One strategy for selective optimization is known as the positivity effect. Elderly people are more likely to perceive, prefer, and remember positive images and experiences than negative ones (Carstensen et al., 2006). Compensation occurs via selective recall: Unpleasant experiences are reinterpreted as inconsequential. For example, with age, stressful events (economic loss; serious illness; the death of friends, family, or, in the future, oneself) are less likely to be considered central to one’s identity. That enables the elderly to be unperturbed by much of what happens; they maintain emotional health via positive self-

The positivity effect is evident in many nations. After taking into account income, education, and gender, adults everywhere report gradually increasing happiness from age 50 on (Blanchflower et al., 2008).

533

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

No Regrets

Many researchers have studied the positivity effect. They have found not only that a positive world view usually increase with age but also that it correlates with believing that life is meaningful (Hicks et al., 2012). Those elders who are highest in positivity (e.g., feeling happy, not frustrated or depressed) are likely to agree strongly that their life has a purpose (e.g., “I have a system of values that guides my daily activities” and “I am at peace with my past”) (Hicks et al, 2012).

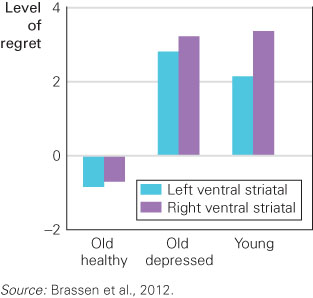

Researchers have measured expressed attitudes and memories as well as brain and body reactions to disappointment. For example, Brassen and colleagues (2012) explored the reactions of adults of various ages to questions such as “When something doesn’t happen as you wish, are you likely to take a greater risk the next time, or are you likely to let go of your disappointment?” Emerging adults might take a greater risk, but emotionally healthy older adults are not likely to. The emotionally healthy elderly react to disappointment by letting it go and thinking positively about going forward (see Figure 15.1).

In this and many other experiments, older adults are found to be able to let bygones be bygones, leading to greater emotional well-

This study also included a group of older adults who had been diagnosed with late-

Other research has also found that depressed older adults are neurologically impaired, particularly in the anterior cingulate cortex, a brain region crucial for processing conflicting emotions and thoughts (Ochsner et al., 2009). Because of the positivity effect, anger, sadness, and disappointment are limited in healthy older people—

The positivity effect is not always dramatic. Consider the details of a different study (Werheid et al., 2010). In four experiments, a total of 132 individuals—

All four experiments showed the positivity effect somewhat, but not dramatically. For instance, in the first experiment, the older adults were slightly better than the younger ones at recognizing happy faces (74 versus 70 percent) and worse at recognizing angry faces (81 versus 84 percent) or neutral faces (65 versus 69 percent). They were also likely to mistakenly claim that the new happy faces were familiar (22 versus 7 percent).

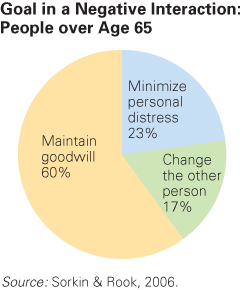

The presence of even a mild positivity effect suggests that elders ignore or move past certain negative realities, such as expressions of anger and frustration. For example, adults in one study were asked about recent instances of personal confrontation (Sorkin & Rook, 2006). More than one-

534

Since their goal was to achieve harmony, the elderly were more likely to compromise instead of insist that they were correct. This led to a happier outcome. As the researchers stated,

[p]articipants whose primary coping goal was to preserve goodwill reported the highest levels of perceived success and the least intense and shortest duration of distress. In contrast, participants whose…goal was to change the other person reported the lowest levels of perceived success and the most intense and longest lasting distress.

[Sorkin & Rook, 2006]

Stratification Theories

A second set of theories, called stratification theories, emphasizes societal forces that place each person in a social strata or level. Such stratification makes it difficult for a person to earn more income, have better health, or live longer than people of their group. Stratification begins from day one, as babies are conceived in societies that are already stratified, or differentiated, by various dimensions such as gender, ethnicity, and SES (Lynch & Brown, 2011).

The problem with stratification is that it results in inequality for reasons beyond the individual. As the decades of life go by, stratification by age, gender, ethnicity, and income become increasingly burdensome, causing double, triple, or even quadruple jeopardy. We describe each of these in turn.

Stratification By AgeAgeism is, of course, stratification by age. Age affects a person’s life in many ways, including income and health. For example, seniority builds in the workplace, increasing income up to a certain point; then employment may stop when a person reaches a given age, with that person perhaps earning a pension but never as much income as before.

This is just one example of the many ways in which industrialized nations segregate elderly people, gradually shutting them out of the mainstream of society as they grow older (Achenbaum, 2005). That harms all generations because it limits social experiences: Younger as well as older people have a narrower perspective on life if they interact only with people their own age.

The most controversial version of age-

Disengagement theory provoked a storm of protest because people feared it justified ageism and social isolation. Many gerontologists insisted that older people need and want new involvements. Some developed an opposing theory, called activity theory, which holds that the elderly seek to remain active with relatives, friends, and community groups. Activity theorists contend that if the elderly disengage, they do so unwillingly (J. R. Kelly, 1993; Rosow, 1985).

Later research has found that elders who are more active are happier, intellectually more alert, and less depressed. This is true at younger ages as well, although some studies find that activity is particularly likely to correlate with high functioning at older ages (Bielak, 2010; Bielak et al., 2012).

535

Both disengagement and activity theories need to be applied with caution, however. Disengagement in one aspect of life (e.g., retiring from employment) does not necessarily mean disengagement overall: Many retirees disengage from work but find new roles and activities to participate in (Freund et al., 2009). The positivity effect, just described, may mean that an older person disengages from emotional events that cause anger, regret, and sadness, while actively enjoying other experiences (Brassen et al., 2012).

A cautionary note comes from research in China. One study found that among the Chinese young-

Stratification By GenderFeminist theory draws attention to stratification that puts males and females on separate tracks through life. From pink or blue blankets for newborns’ bassinets to flowers or stripes for nursing home bedsheets, gender is signalled throughout life. These signals alert everyone—

The implications of gender divergence are illustrated by a study of caregiving among older married couples. Both sexes provided care if their spouse became needy, but they did so in opposite ways: Women quit their jobs, whereas men worked longer. To be specific, employed women whose husbands needed care were five times more likely to retire than were other employed women. By contrast, employed husbands whose wife needed care retired only half as often as other men (Dentinger & Clarkberg, 2002).

Note, however, that both partners sacrifice. Men stayed on the job so they could keep insurance and hire household help, and women quit to provide personal care. Both sexes followed the gender stratification of decades earlier: Women were socialized to be caregivers, and men’s employment patterns (not part-

Irrational, gender-

536

In another example of stratification, women typically marry men a few years older than they are and then outlive them. Especially if they lived in rural areas (as most North Americans did until about 1950), married women often relied on their husbands to drive, to manage money, and to keep up with politics. Then, if the husband died, past gender stratification led to isolation, poverty, and dependence among the oldest-

Men, too, may be harmed. For instance, boys are taught that males are stoic, repressing emotions and avoiding medical care. Is that why, in every nation, adult women outlive men? This could be biological (protective hormones), but it could result from lifelong stratification, making men more vulnerable in old age.

Stratification By EthnicityLike age and gender, ethnic background affects every aspect of development throughout life, including education, health, place of residence, and employment. Stratification theory suggests that these factors accumulate, creating large discrepancies by old age that leave ethnic minority seniors at risk of becoming marginalized (National Advisory Council On Aging, 2005).

When one considers Canadian seniors, stratification by ethnicity is probably most evident among immigrants, especially those who arrived recently, and among Aboriginal peoples. In 2006, about 30 percent of Canadian seniors were immigrants, many of them from visible minorities (Ng, 2010). Aboriginal peoples accounted for 1 percent of Canada’s seniors (Chief Public Health Officer, 2010).

ESPECIALLY FOR Social Scientists The various social science disciplines tend to favour different theories of aging. Can you tell which theories would be more acceptable to psychologists and which to sociologists?

In general, psychologists favour self theories, and sociologists favour stratification theories. Of course, each discipline respects the other, but each believes that its perspective is more honest and accurate.

Common problems faced by ethnic minority and Aboriginal seniors include greater rates of poverty and illness and, for Aboriginal peoples, shorter life expectancies. In 2001, 13 percent of Aboriginal seniors, compared to 7 percent of non-

Higher poverty rates are also present among elderly immigrants, particularly those who are recent immigrants as compared to those who have been in the country longer than 10 years (Eigersma, 2010). For example, in 2003, 26 percent of recent immigrant seniors were in the lowest income quartile compared with 12 percent of long-

A particular form of ethnic stratification may affect immigrant elders who find themselves dependent on their adult children within a culture stratified against both the old and the immigrant. Many traditional cultures expect younger generations to care for the elderly personally, but North American families tend to be nuclear families, not extended ones.

For some cultures, the traditional notion of adult children caring for their aging parents remains strong. In some Chinese families, for example, the thought of placing an ailing and aged parent in a nursing home may conflict with their sense of responsibility. One recent response to this problem has been the appearance of ethnoculturally focused nursing homes such as the Yee Hong Geriatric Care Centre that services the Chinese community in Mississauga, Ontario. About 10 Asian-

537

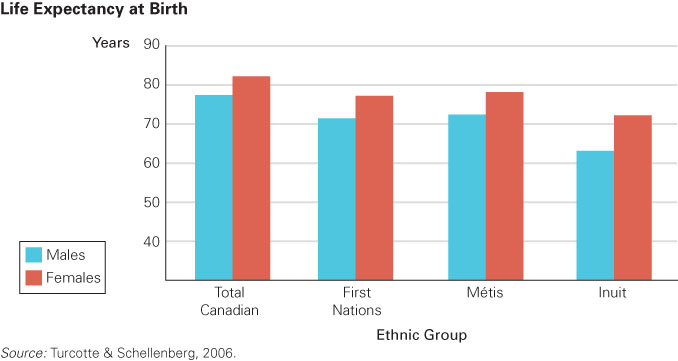

Since poverty often has negative impacts on a person’s health, it comes as no surprise that in 2001—

A 2008 report for Statistics Canada found discrepancies in the mortality rates among various ethnic groups but especially for Aboriginal peoples. First Nations, Métis, and Inuit had substantially higher mortality rates than non-

OBSERVATION QUIZ

Which Aboriginal group has the lowest life expectancy? Why might this be the case?

The Inuit. They are less likely to have access to health care services; their rates of smoking are higher than those of other populations; they are more likely to live in poorer conditions (crowded homes, unsafe drinking water); their levels of education are lower, which correlates with health and well-

Stratification By SESFinally, the pivotal influence on the well-

538

The problem may begin even before birth, since epigenetic factors—

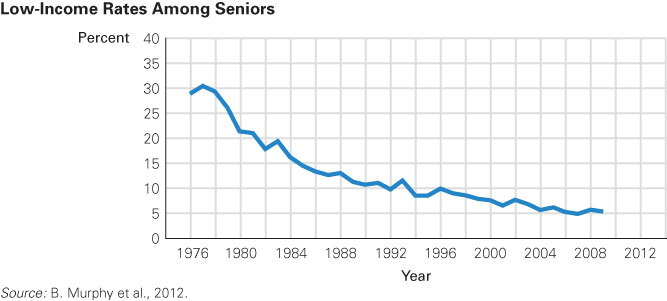

In 2010, 5.3 percent of seniors in Canada were living in poverty—

Perhaps the main reason for the decrease was the institution of the Canada Pension Plan and Quebec Pension Plan in 1966. Canadian seniors can also access two other government transfer programs:

- Old Age Security. Almost all Canadians older than 65 receive OAS, which is an income supplement that averages about $450 a month.

- Guaranteed Income Supplement. This provides additional funds to low-

income seniors who are enrolled in OAS and meet certain other requirements.

In addition, some seniors have access to their own savings or private pension plans that they enrolled in at work.

Despite the drop in poverty rates among seniors, one group that remains vulnerable to low income in old age is women, especially those older than 75 and who have been widowed or are living alone for other reasons. Women often receive less than men from government pension plans because the benefits are usually linked to a person’s employment history. In the period between 2006 and 2010, the number of Canadian seniors living below LICO increased by about 160 000, and 60 percent of them were women (Conference Board of Canada, 2013a).

One important financial problem for the elderly is that inflation makes retirement income worth less than half of what it was when that money was first set aside. Those middle-

539

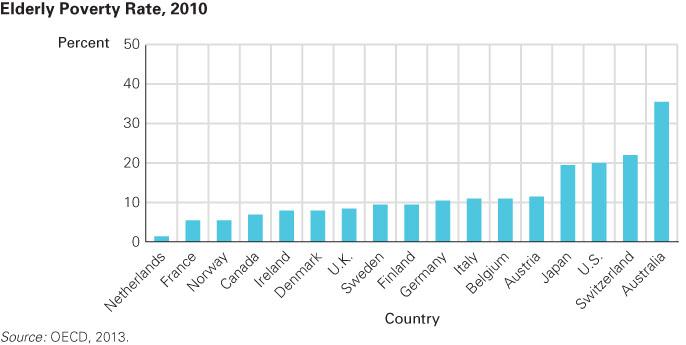

Internationally, stratification by income for the elderly varies a great deal (see Figure 15.5). Some nations provide free health care and heavily subsidized senior residences for everyone. One of these is Denmark, which also has the highest proportion of happy seniors. By contrast, other nations provide nothing at all, expecting family members to care for the elderly. In several Asian nations, it is illegal for adult children not to provide for their parents.

This is a developmental issue to which applying a cross-

KEY Points

- Self theories of late adulthood stress that people try to remain themselves, achieving integrity and not despairing.

- The positivity effect protects the self, as elders take pleasure and pride in who they are.

- The disengagement theory holds that as people age, they relinquish past roles and withdraw from life’s action.

- Activity theory suggests that, if the aged disengage, it is not by choice. Contrary to disengagement theory, it suggests societies should encourage activity in old age.

- Gender, ethnicity, and economic strata all place people on particular paths for life: This stratification may be particularly harmful in late adulthood.