2.2 From Zygote to Newborn

The most dramatic and extensive transformation of the entire life span occurs before birth. To make it easier to study, prenatal development is often divided into three main periods. The first two weeks are called the germinal period; the third through the eighth week is the embryonic period; the ninth week until birth is the fetal period (see TABLE 2.2 for alternative terms).

Popular and professional books use various phrases to segment pregnancy. The following comments may help clarify the phrases used.

|

Germinal: The First 14 Days

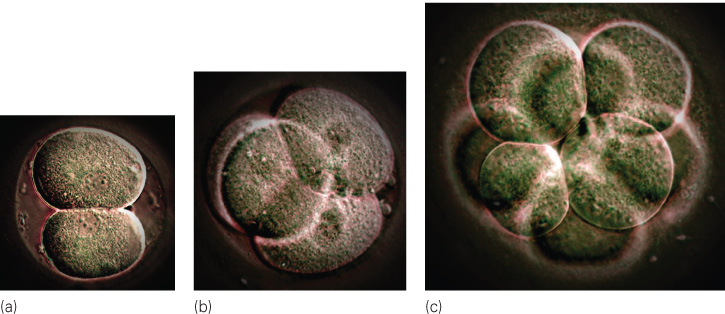

Within hours after conception, the zygote begins duplication and division. First, the 23 pairs of chromosomes carrying all the genes duplicate, forming two complete sets of the genome. These two sets move toward opposite sides of the zygote, and the single cell splits neatly down the middle into two cells, each containing the original genetic code. These two cells duplicate and divide, becoming four, which themselves duplicate and divide, becoming eight, and so on. If the two-

59

Those first cells are stem cells, able to direct production of any other cell and thus to become a complete person. After about the eight-

About a week after conception, the multiplying cells (now numbering more than 100) separate into two distinct masses. The outer cells form a shell that will become the placenta (the organ that surrounds and protects the developing creature), and the inner cells form a nucleus that will become the embryo.

The first task of the outer cells is implantation—that is, to embed themselves in the nurturing lining of the uterus. This is far from automatic; about 50 percent of natural conceptions and an even larger percentage of in vitro conceptions never implant (see TABLE 2.3). Most new life ends before an embryo begins (Sadler, 2012).

|

The Germinal Period An estimated 60 percent of all zygotes do not grow or implant properly and thus do not survive the germinal period. Many of these organisms are abnormal; few women realize they were pregnant. |

|

The Embryonic Period About 20 percent of all embryos are aborted spontaneously, most often because of chromosomal abnormalities. This is usually called an early miscarriage. |

|

The Fetal Period About 5 percent of all fetuses are aborted spontaneously before viability at 22 weeks or are stillborn, defined as born dead after 22 weeks. This is much more common in developing nations. |

|

Birth Because of all these factors, only about 31 percent of all zygotes grow and survive to become living newborn babies. Age is crucial. One estimate is that less than 3 percent of all conceptions after age 40 result in live births. |

|

Sources: Bentley & Mascie- |

Embryo: From the Third Through the Eighth Week

PETIT FORMAT/SCIENCE SOURCE

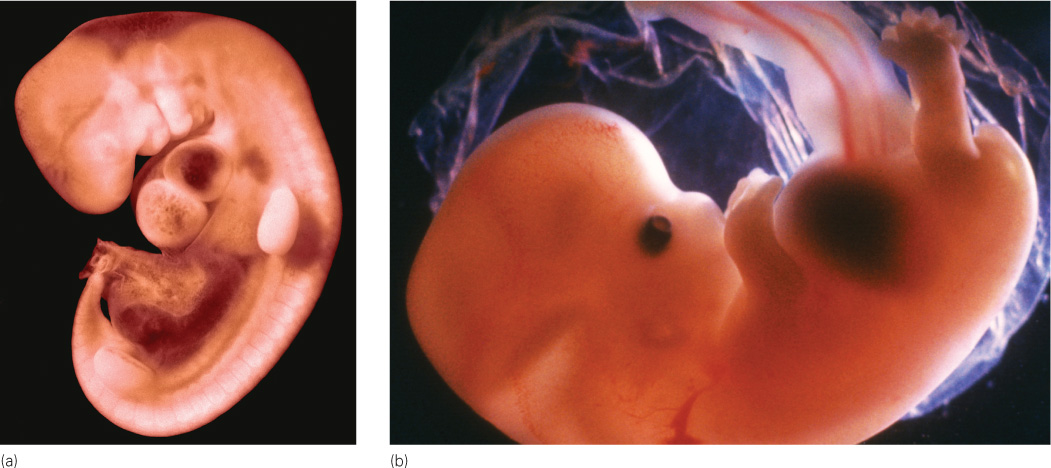

The start of the third week after conception initiates the embryonic period, during which the formless mass of cells becomes a distinct being—

60

At about day 14, a thin line (called the primitive streak) appears down the middle of the embryo, becoming the neural tube 22 days after conception and eventually developing into the central nervous system, brain, and spinal column (Sadler, 2012). The head appears in the fourth week, as eyes, ears, nose, and mouth start to form. Also in the fourth week, a minuscule blood vessel that will become the heart begins to pulsate.

By the fifth week, buds that will become arms and legs emerge. The upper arms and then forearms, palms, and webbed fingers grow. Legs, knees, feet, and webbed toes, in that order, are apparent a few days later, each having the beginning of a skeletal structure. Then, 52 and 54 days after conception, respectively, the fingers and toes separate (Sadler, 2012).

As you can see, prenatally, the head develops first, in a cephalocaudal (literally, “head-

At the end of the eighth week after conception (56 days), the embryo weighs just 1 gram and is about 2½ centimetres long. It has all the organs and body parts (except sex organs) of a human being, including elbows and knees. It moves frequently, about 150 times per hour, but such movement is random and imperceptible to the mother, who may not even realize that she is pregnant.

Fetus: From the Ninth Week Until Birth

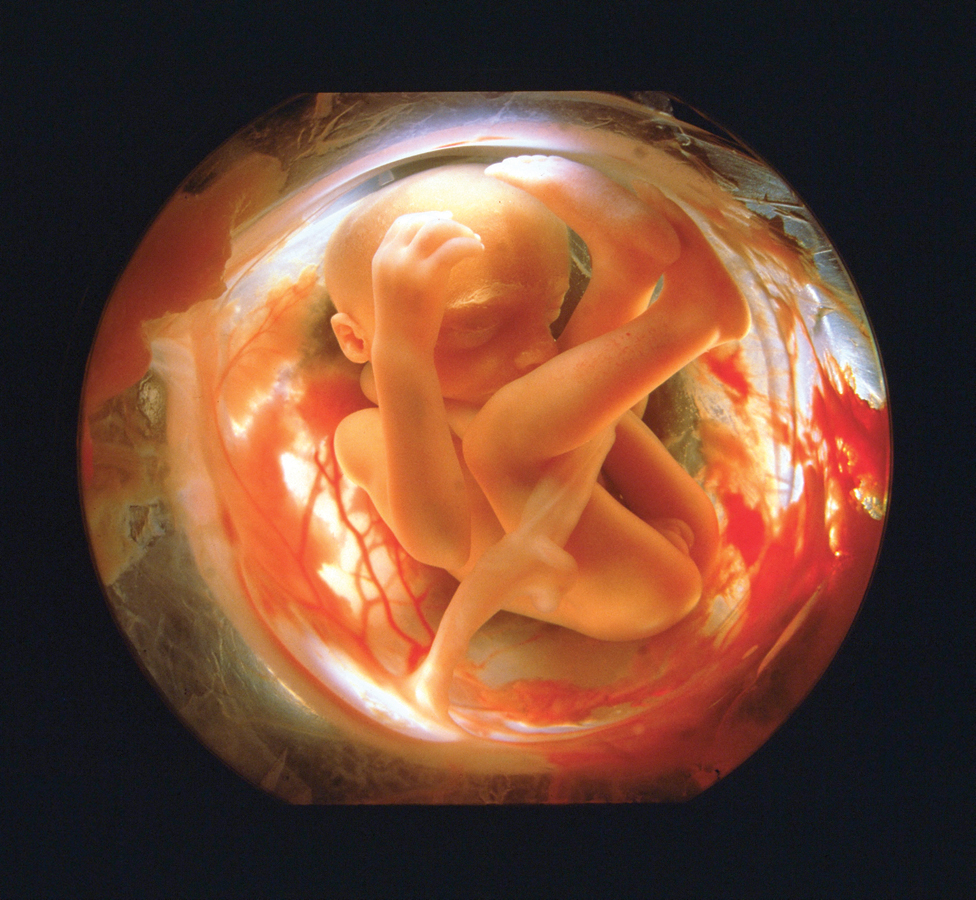

The organism is called a fetus from the ninth week after conception until birth. The fetal period encompasses dramatic change, from a tiny, sexless creature smaller than the final joint of your thumb to a boy or girl about 51 centimetres long.

In the ninth week, sex organs develop, soon visible via ultrasound (also called sonogram). The male fetus experiences a rush of the hormone testosterone, affecting the brain (Morris et al., 2004; Neave, 2008).

By 3 months, the fetus weighs about 87 grams and is about 7.5 centimetres long. Of course, fetal growth rates do vary—

61

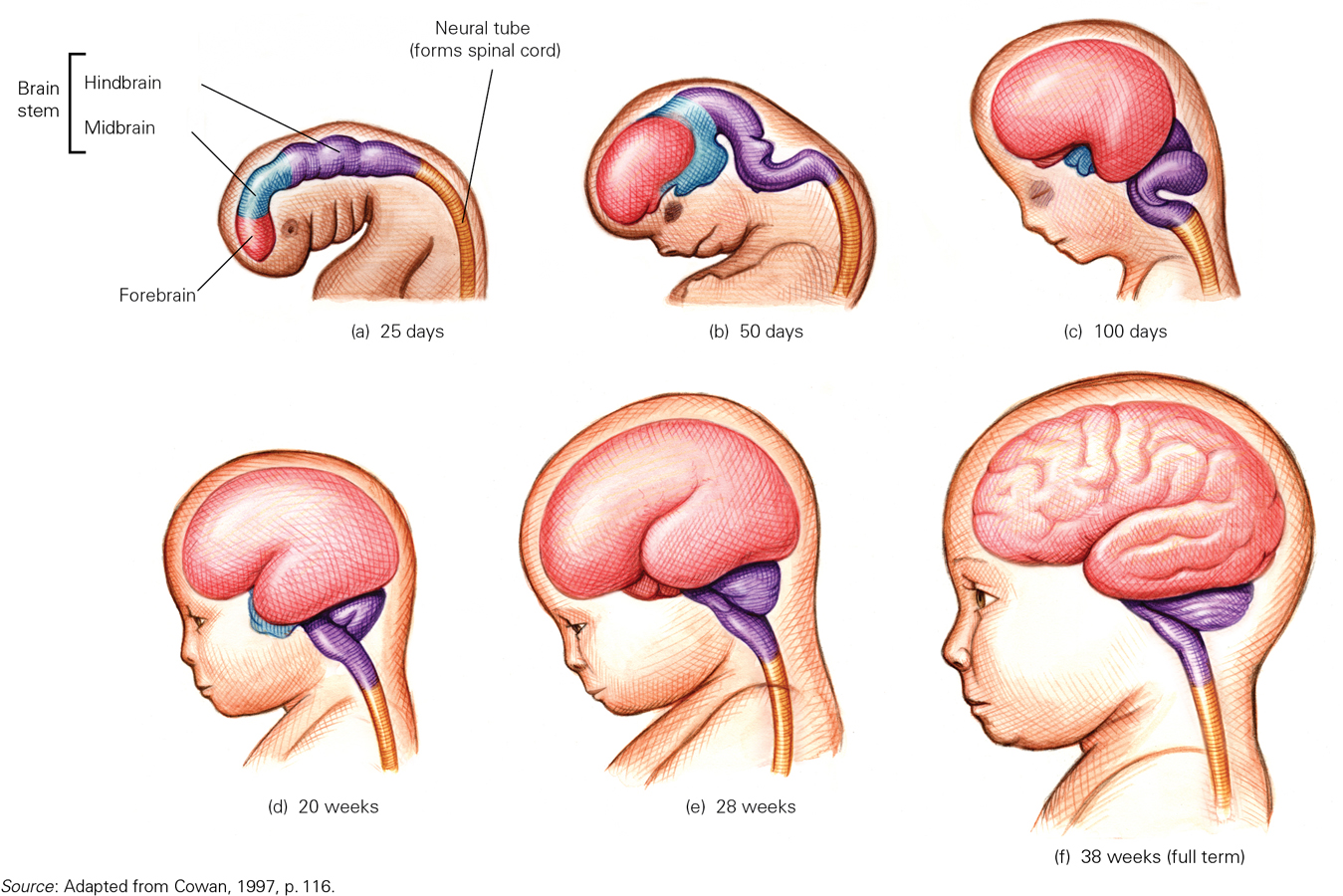

As prenatal growth continues, the cardiovascular, digestive, and excretory systems develop. The brain increases about six times in size from the fourth to the sixth month, developing many new neurons (neurogenesis) and synapses (synaptogenesis). Indeed, up to half a million brain cells per minute are created at peak growth during mid-

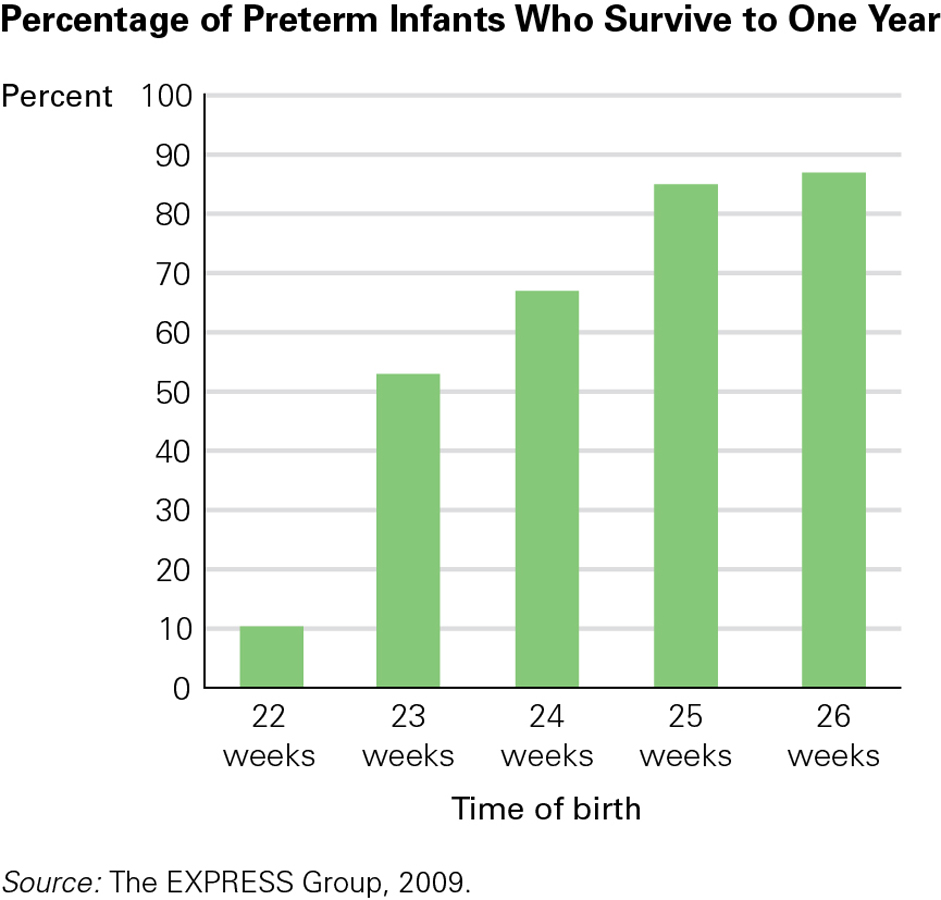

This brain growth is critical because it enables regulation of all the body functions, including breathing (Johnson, 2010). That allows the fetus to reach the age of viability, when a preterm newborn might survive. Thanks to intensive medical care, the age of viability decreased dramatically in the twentieth century, but it now seems stuck at about 22 weeks (Pignotti, 2010) because even the most advanced technology cannot maintain life without some brain response.

According to an international report published in 2012, Canada has a preterm birth rate of almost 8 percent, while the U.S. rate is 12 percent, the worst among G8 countries (Howson et al., 2012). Canada’s preterm birth rate has increased almost 25 percent from the early 1990s, when it stood at 6.5 percent (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2009). Reasons for the increase include the greater number of older women who are having babies and the rise in rates of multiple pregnancies, often the result of taking fertility drugs. Other factors include increased rates of obesity, which can lead to high blood pressure and diabetes, and more cases of medically induced labour and Caesarean sections before pregnancies reach full term (Howson et al., 2012).

As the brain matures and the axons, or nerve fibres, connect, the organs of the body begin to work in harmony, fetal movement as well as heart rate quiet down during rest, and the heart beats faster during activity (which may be when the mother is trying to sleep).

Attaining the age of viability simply means that life outside the womb is possible (see Figure 2.5). Each day of the final three months improves the odds, not only of survival but also of life without disability (Iacovidou et al., 2010). A preterm infant born in the seventh month is a tiny creature requiring intensive care for each gram of nourishment and every shallow breath. The care and complications of preterm infants (especially conditions associated with low birth weight) are discussed at the end of this chapter. Usually, however, full-

By full term, human brain growth is so extensive that the cortex (the brain’s advanced outer layers) forms several folds in order to fit into the skull (see Figure 2.6). Although some large mammals (whales, for instance) have bigger brains than humans (although not bigger in relation to one’s size), no other creature needs as many folds as humans do, because the human cortex contains much more material than the brains of non-

62

63

Finally, a Baby

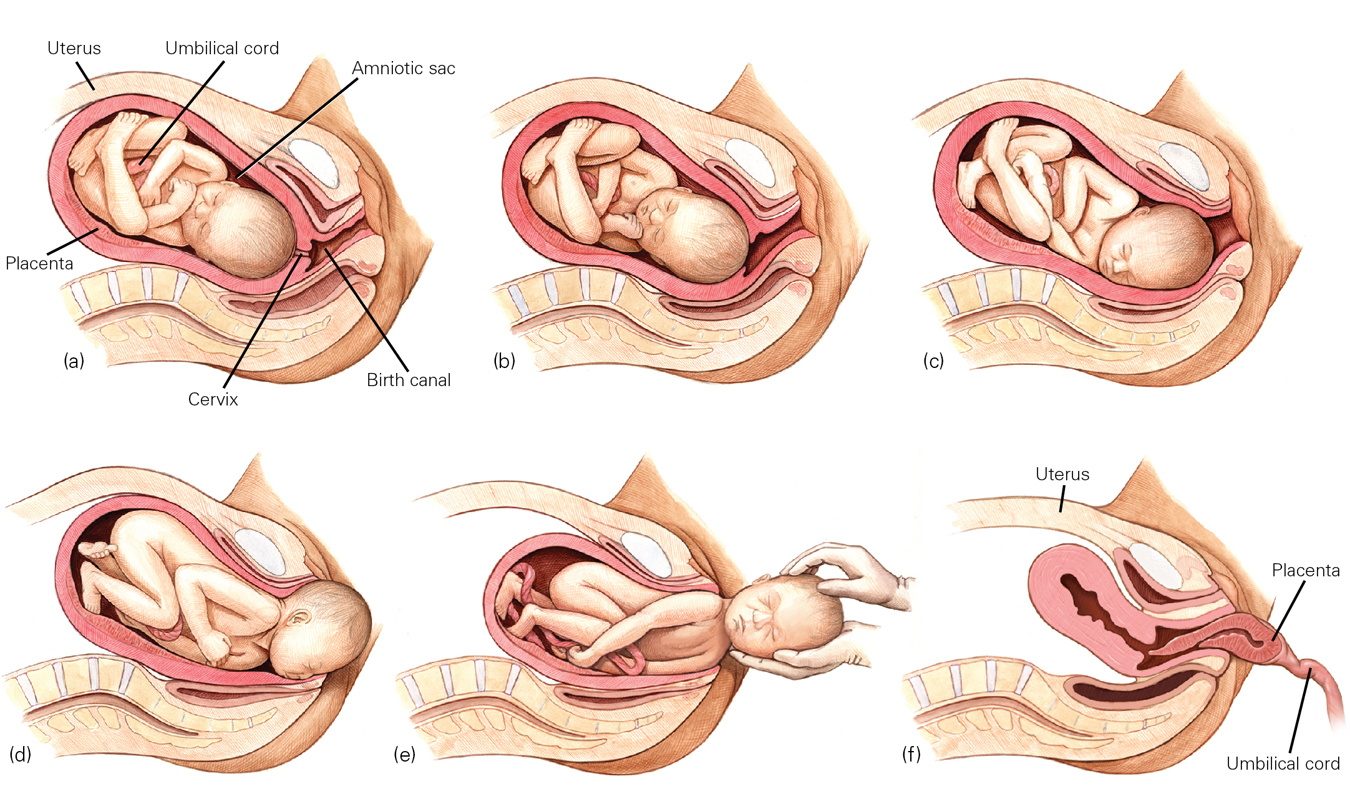

About 38 weeks (266 days) after conception, the fetal brain signals the release of hormones, specifically oxytocin, which prepares the fetus for delivery and starts labour. The average baby is born after 12 hours of active labour for first births and 7 hours for subsequent births (Moore & Persaud, 2003), although labour may take twice or half as long. The definition of “active” labour varies, which is one reason some women believe they are in active labour for days and others say 10 minutes. (Figure 2.7 shows the stages of birth.)

Women’s birthing positions also vary—

Average Prenatal Weights*

| Period of Development | Weeks Past Conception | Average Weight | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| End of embryonic period | 8 | 1 g | Most common time for spontaneous abortion (miscarriage). |

| End of first trimester | 13 | 85 g | |

| At viability (50/50 chance of survival) | 22– |

565– |

A birth weight less than 1000 g is extremely low birth weight (ELBW). |

| End of second trimester | 26– |

900– |

Less than 1500 g is very low birth weight (VLBW). |

| End of preterm period | 35 | 2500 g | Less than 2500 g is low birth weight (LBW). |

| Full term | 38 | 3400 g | Between 2500 and 4000 g is considered normal weight. |

| *Actual weights vary. For instance, normal full- |

|||

64

Preferences and opinions on birthing positions (as on almost every other aspect of prenatal development and birth) are partly cultural and partly personal. In general, physicians find it easier to see the head emerge if the woman lies on her back. However, many women find it easier to push the fetus out if they sit up. Neither of these generalities is true for every individual.

The Newborn’s First MinutesNewborns usually breathe and cry on their own. Between spontaneous cries, the first breaths of air bring oxygen to the lungs and blood, and the infant’s colour changes from bluish to pinkish. (Pinkish refers to blood colour, visible beneath the skin, and applies to newborns of all hues.) Eyes open wide; tiny fingers grab; even tinier toes stretch and retract. The full-

One assessment of newborn health is the Apgar scale (see TABLE 2.4), first developed by Dr. Virginia Apgar. When she earned her MD in 1933, Apgar wanted to work in a hospital but was told that only men did surgery. Consequently, she became an anesthesiologist. Apgar saw that “delivery room doctors focused on mothers and paid little attention to babies. Those who were small and struggling were often left to die” (Beck, 2009, p. D-

| Five Vital Signs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | Colour | Heartbeat | Reflex Irritability | Muscle Tone | Respiratory Effort |

| 0 | Blue, pale | Absent | No response | Flaccid, limp | Absent |

| 1 | Body pink, extremities blue | Slow (below 100) | Grimace | Weak, inactive | Irregular, slow |

| 2 | Entirely pink | Rapid (over 100) | Coughing, sneezing, crying | Strong, active | Good; baby is crying |

| Source: Apgar, 1953. | |||||

65

Since 1950, birth attendants worldwide have used the Apgar (often using the name as an acronym: Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity, and Respiration) at one minute and again at five minutes after birth, assigning each vital sign a score of 0, 1, or 2. If the five-

Medical Assistance at BirthThe specifics of birth depend on the parents’ preparation, the position and size of the fetus, and the customs of the culture. In developed nations, births almost always include sterile procedures, electronic monitoring, and drugs to dull pain or speed contractions. In addition, many aspects of birth depend on who delivers the baby—

Midwives are as skilled at delivering babies as physicians, but in most nations only medical doctors perform surgery, such as Caesarean sections (C-sections), whereby the fetus is removed through incisions in the mother’s abdomen. A new endeavour in Africa to teach midwives to perform Caesareans is projected to save a million lives per year.

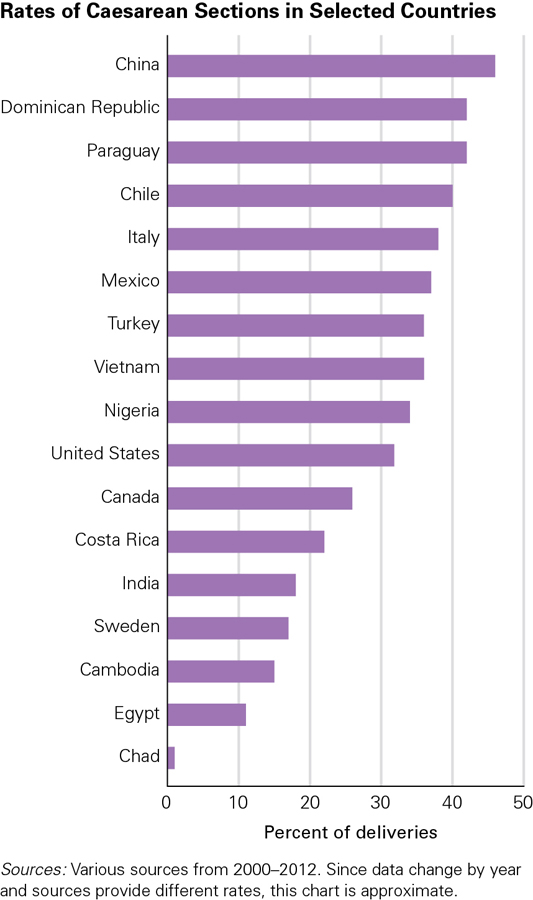

Caesareans are usually safe for mother and baby and have many advantages for hospitals (easier to schedule, quicker, and more expensive than vaginal deliveries, which means that hospitals make more money on C-

According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), there are no agreed-

For reasons nobody quite understands, C-

Examining the rates in other countries, China’s rate of Caesareans increased from 5 percent in 1991 to 46 percent in 2008 (Guo et al., 2007; Juan, 2010). In the United States, the rate rose every year between 1996 and 2009 (from 21 percent to 34 percent, with notable state variations, from 22 percent in Utah to 39 percent in Florida) (Menacker & Hamilton, 2010).

Less studied is the epidural, an injection in a particular part of the spine of the labouring woman to alleviate pain. Epidurals are often used in hospital births, but they increase the rate of Caesarean sections and decrease the readiness of newborn infants to suck immediately after birth (Bell et al., 2010).

66

Another medical intervention is induced labour, in which labour is started, speeded, or strengthened with a drug. The rate of induced labour in many developed nations has more than doubled since 1990, up to 20 to 25 percent. The reasons are sometimes medically warranted (such as when a woman develops eclampsia, which could kill the fetus) and sometimes not (Grivell et al., 2012). Induction increases the rate of complications, including the need for Caesareans.

Alternatives to Hospital TechnologyQuestions of costs and benefits abound. For instance, C-

Most Canadian births now take place in hospital labour rooms with high-

In some European nations, many births occur at home by plan (30 percent in the Netherlands). In Europe, home births have fewer complications than in hospitals—

In most hospitals in the twentieth century, women giving birth laboured alone. Fathers and other family members were kept away and only doctors and nurses attended the birth. No longer. Almost everyone now agrees that other people should always be with a labouring woman. Relatives or friends are often present, midwives have often replaced doctors, and sometimes a doula provides practical as well as emotional support for the mother and other family members. Many studies have found that doulas benefit anyone giving birth, rich or poor, married or not (Vonderheid et al., 2011). For example, in one study 420 middle-

67

In Canada, women can also make use of a licensed midwife instead of an obstetrician. Besides assisting at a baby’s birth, midwives provide various other services, including physical examinations and screening tests. They work in partnership with other health professionals. In 2009, midwives attended about 10 percent of all births in Ontario, and 20 percent of those births occurred at home (College of Midwives of Ontario, n.d.).

The New Family

The fact that mothers are now less lonely during labour stems in part from the recognition that people are social creatures, seeking support from their families and their societies. Birth marks the beginning of a new family; ideally, each family member—

The NewbornBefore birth, developing humans already contribute to their families via fetal movements and hormones that cause protective impulses in the mother early in pregnancy and nurturing impulses at the end (Konner, 2010). The appearance of the newborn (big hairless head, tiny feet, and so on) stirs the human heart, as is evident in adults’ brain activity and heart rates when they see a baby.

Newborns are responsive social creatures, listening, staring, sucking, and cuddling. In the first day or two after birth, a professional might administer the Brazelton Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (NBAS), which records 46 behaviours, including 20 reflexes. Parents watching the NBAS are amazed at their newborn’s competence—

- Reflexes that maintain oxygen supply. The breathing reflex begins even before the umbilical cord, with its supply of oxygen, is cut. Additional reflexes that maintain oxygen are reflexive hiccups and sneezes, as well as thrashing (moving the arms and legs about) to escape something that covers the face.

- Reflexes that maintain constant body temperature. When infants are cold, they cry, shiver, and tuck their legs close to their bodies. When they are hot, they try to push away blankets and then stay still.

- Reflexes that manage feeding. The sucking reflex causes newborns to suck anything that touches their lips—

fingers, toes, blankets, and rattles, as well as natural and artificial nipples of various textures and shapes. The rooting reflex causes babies to turn their mouths toward anything that brushes against their cheeks— a reflexive search for a nipple— and start to suck. Swallowing is another reflex that aids feeding, as is crying when the stomach is empty and spitting up when full.

Each of these 13 reflexes (in italics) normally causes a caregiving reaction, as the new parents do what seems necessary to protect their newborn. Thus reflexes affect human interaction. In addition, newborn senses are also responsive to people: New babies listen more to voices than to traffic, for instance, and they stare at faces more than at machines. Typically, when a baby stares at a new parent, the parent talks and the baby listens.

68

New FathersFrom conception on, fathers’ involvement in their children’s lives is vitally important and has a strong impact on children’s development. Fathers-

After their children’s birth, fathers are involved in the day-

In Canada, fathers’ increased use of paid parental leave from work is evidence of their increased involvement in the care of their children. In 2000, only 3 percent of eligible Canadian fathers took this time off, but by 2006 the rate had increased to 20 percent. A large part of the increase was due to rule changes, especially in Quebec where the provincial government instituted a “daddy days” policy that allows for up to five weeks of paid paternal leave that cannot be transferred to the mother.

69

The move away from traditional parenting roles is evident among European-

New MothersAbout half of all women experience physical problems after giving birth, such as incisions from a C-

Sometimes the first sign that something is amiss is that the mother is euphoric after birth. She cannot sleep, stop talking, or keep from worrying about the newborn. Some of this is normal, but family members and medical personnel need to be alert, as a crash might follow the high.

Maternal depression can have a long-

From a developmental perspective, causes of postpartum depression (such as marital problems) sometimes predate pregnancy; others (such as financial stress) occur during pregnancy; others correlate with birth (especially if the mother is alone); and still others (health, feeding, or sleeping problems) are specific to the particular infant. Successful breastfeeding may mitigate maternal depression, in part by increasing levels of oxytocin, a bonding hormone. This is one of the many reasons a lactation counsellor (who helps with breastfeeding techniques) may be a crucial member of the new mother’s support team.

BondingThe active involvement of both parents in pregnancy, birth, and newborn care helps establish the parent-infant bond, the strong, loving connection that forms as parents hold, examine, and feed their newborn. Factors that encourage parents (biological or adoptive) to nurture their newborns have lifelong benefits, proven with mice, monkeys, and humans (Champagne & Curley,2010).

Early skin-

Kangaroo care was first used with low-

70

KEY Points

- The germinal period ends 2 weeks after conception with implantation. This period is followed by the development of the embryo, as the creature takes shapes.

- At 8 weeks after conception, fetal life begins, with 7 months of brain and body maturation, as well as life-

saving weight gain, from about 85 grams at 3 months to about 3 kilograms at full term. - Full-

term birth is a natural event, assisted by drugs and other medical measures in developed countries. - Human social interaction begins even before birth, as mothers, fathers, and babies respond to each other.