3.3 Surviving in Good Health

Although precise worldwide statistics are unavailable, at least 10 billion children were born between 1950 and 2010. More than 2 billion of them died before age 5 years. Although 2 billion is far too many, twice as many would have died without recent public health measures. As best we know, in earlier centuries more than half of all newborns died in infancy.

110

Better Days Ahead

In the twenty-

| Country | Nuumber of Deaths per 1000 | Country | Number of Deaths per 1000 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iceland | 2** | Russia | 12* |

| Japan | 3** | Mexico | 17** |

| Singapore | 3** | China | 18** |

| Sweden | 3** | Brazil | 19** |

| Italy | 4** | Vietnam | 23** |

| Australia | 5* | Iran | 26** |

| Spain | 5** | Philippines | 29** |

| United Kingdom | 5* | India | 63** |

| Canada | 6* | Nigeria | 143* |

| New Zealand | 6* | Afghanistan | 149* |

| United States | 8* | Sierra Leone | 174* |

| *Reduced by at least one- |

|||

| **Reduced by half or more since 1990. | |||

| Source: World Health Organization, 2012b. | |||

The world death rate in the first five years of life has dropped about 2 percent per year since 1990 (Rajaratnam et al., 2010). Most nations have improved markedly on this measure since 1990. Only when war destroys families and interferes with public health measures (as it has in Afghanistan) are nations not improving this statistic.

Public health measures (clean water, nourishing food, immunization) are the main reasons for the higher rate of survival. When women realize that a newborn is likely to survive to adulthood, they have fewer babies, and that advances the national economy. Infant survival and maternal education are the two main reasons the world’s 2010 fertility rate is half what the rate was in 1950 (Bloom, 2011; Lutz & Samir, 2011).

If doctors and nurses were available in underserved areas, the current infant death rate would be cut in half—

One innovation has cut the malaria death rate in half: bed nets treated with insect repellant that drape over sleeping areas (Roberts, 2007) (see photo). Over the long term, however, systemic prevention means making mosquitos sterile—

Immunization

Immunization primes the body’s immune system to resist a particular disease. Immunization (also called vaccination) is said to have had “a greater impact on human mortality reduction and population growth than any other public health intervention besides clean water” (J. P. Baker, 2000).

No immunization is yet available for malaria. Thousands of scientists are working to develop one, and some clinical trials seem promising (Vaughan & Kappe, 2012). However, immunization has been developed for measles, mumps, whooping cough, smallpox, pneumonia, polio, and rotavirus, which no longer kill hundreds of thousands of children each year.

It used to be that the only way to become immune to these diseases was to catch them, sicken, and recover. The immune system would then produce antibodies to prevent recurrence. Beginning with smallpox in the nineteenth century, doctors discovered that giving a vaccine—

Specific DiseasesStunning successes in immunization include the following:

- Smallpox, the most lethal disease for children in the past, was eradicated worldwide as of 1971. Vaccination against smallpox is no longer needed.

111

- Polio, a crippling and sometimes fatal disease, is rare. Widespread vaccination, begun in 1955, eliminated polio in the Americas. Only 784 cases were reported anywhere in the world in 2003. In the same year, however, rumours halted immunization in northern Nigeria. Polio reappeared, sickening 1948 people in 2005, almost all in West Africa. Then public health workers and community leaders campaigned to increase immunization, and Nigeria’s polio rate plummeted. Meanwhile, poverty and new conflicts in South Asia prevented immunization (De Cock, 2011; World Health Organization, 2012a). Worldwide, 223 cases were reported in 2012. In 2013, only three countries, Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan, had an epidemic of polio (World Health Organization, 2013a). Since 1988, there has been a 99 percent decrease in cases (See Figure 3.6).

FIGURE 3.6 Not Yet Zero Many public health advocates hope polio will be the next infectious disease to be eliminated worldwide, as is the case in almost all of North America. The number of cases has fallen dramatically worldwide (a). However, there was a discouraging increase in polio rates from 2003 to 2005 (b).

FIGURE 3.6 Not Yet Zero Many public health advocates hope polio will be the next infectious disease to be eliminated worldwide, as is the case in almost all of North America. The number of cases has fallen dramatically worldwide (a). However, there was a discouraging increase in polio rates from 2003 to 2005 (b). - Measles (rubeola, not rubella) is disappearing, thanks to a vaccine developed in 1963. Prior to that time, about 300 000 children were affected by measles each year in Canada alone. About 300 of these children died each year and another 300 suffered permanent brain damage. After the introduction of the measles vaccine, the number of cases dropped dramatically to about 50 a year (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2014).

112

- Canada began publicly funding a vaccination program for varicella (chicken pox) in 2004. Since then, hospitalization rates for varicella dropped from an average of 288 per year to 114 per year (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2012c).

ESPECIALLY FOR Nurses and Pediatricians A mother refuses to have her baby immunized because she wants to prevent side effects. She wants your signature for a religious exemption, which in some jurisdictions allows the mother to refuse vaccination because she says it is for religious reasons. What should you do?

It is difficult to convince people that their ideas may be harmful, although you should try. In this case, listen respectfully and then describe specific instances of serious illness or death from a childhood disease. Suggest that the mother ask her grandparents if they knew anyone who had polio, tuberculosis, or tetanus (they probably did). If you cannot convince this mother, do not despair: Vaccination of 95 percent of toddlers helps protect the other 5 percent. If the mother has religious reasons, talk to her clergy adviser.

Immunization protects children not only from temporary sickness, but also from complications, including deafness, blindness, sterility, and meningitis. Sometimes the damage from illness is not apparent until decades later. Childhood mumps, for instance, can cause sterility and doubles the risk of schizophrenia (Dalman et al., 2008).

Some people cannot be safely immunized, including the following:

- Embryos, who may be born blind, deaf, and brain-

damaged if their pregnant mother contracts rubella (German measles) - Newborns, who may die from a disease that is mild in older children

- People with impaired immune systems (HIV-

positive, aged, or undergoing chemotherapy), who can become deathly ill.

Fortunately, each vaccination of a child stops transmission of the disease and thus protects others, a phenomenon called herd immunity. Although specifics vary by disease, usually if 90 percent of the people in a community (a herd) are immunized, the disease does not spread to those who are vulnerable. Without herd immunity, some community members die of a “childhood” disease.

Problems With ImmunizationSome infants react to immunization by being irritable or even feverish for a day or so, to the distress of their parents. In addition, many parents are concerned about the potential for even more serious side effects. Whenever something seems to go amiss with vaccination, the media broadcasts it, which frightens parents. As a result, the rate of missed vaccinations has been rising over the past decade. This horrifies public health workers, who, taking a longitudinal and society-

Doctors agree that vaccines “are one of the most cost-

Nutrition

Infant mortality worldwide has plummeted in recent years. Several reasons have already been mentioned: fewer sudden infant deaths (explained in Chapter 1), advances in prenatal and newborn care (explained in Chapter 2), and, as you just read, immunization. One more measure has made a huge difference: better nutrition.

Breast is BestIdeally, nutrition starts with colostrum, a thick, high-

113

SELECTSTOCK/GETTY IMAGES

Babies who are exclusively breastfed are less often sick. In infancy, breast milk provides antibodies against any disease to which the mother is immune and decreases allergies and asthma. Disease protection continues throughout life, because babies who are exclusively breastfed for 6 months are less likely to become obese (Huh et al., 2011) and thus less likely to develop diabetes and heart disease.

Breast milk is especially protective for preterm babies; if a preterm baby’s mother cannot provide breast milk, physicians recommend milk from another woman (Schanler, 2011). (Once a woman has given birth, her breasts produce milk for decades if they continue to be stimulated.) In addition, the specific fats and sugars in breast milk make it more digestible and better for the brain than any substitute (Drover et al., 2009; Riordan, 2005). (See TABLE 3.2 for other benefits of breast milk.)

|

For the Baby Balance of nutrition (fat, protein, etc.) adjusts to age of baby Breast milk has micronutrients not found in formula Less infant illness, including allergies, ear infections, stomach upsets Less childhood asthma Better childhood vision Less adult illness, including diabetes, cancer, heart disease Protection against many childhood diseases, since breast milk contains antibodies from the mother Stronger jaws, fewer cavities, advanced breathing reflexes (less SIDS) Higher IQ, less likely to drop out of school, more likely to attend college or university Later puberty, less teenage pregnancy Less likely to become obese or hypertensive by age 12 |

For the Mother Easier bonding with baby Reduced risk of breast cancer and osteoporosis Natural contraception (with exclusive breastfeeding, for several months) Satisfaction of meeting infant’s basic need No formula to prepare; no sterilization Easier travel with the baby For the Family Increased survival of other children (because of spacing of births) Increased family income (because formula can be expensive) Less stress on father, especially at night |

The composition of breast milk adjusts to the age of the baby, with milk for premature babies distinct from that for older infants. Quantity increases to meet the demand: Twins and even triplets can grow strong while being exclusively breastfed for months.

Not all mothers are able to breastfeed as some may have health conditions or take medication that could harm the infant. Formula feeding is preferable only in unusual or challenging cases, such as when the mother is HIV-

Doctors worldwide recommend breastfeeding with no other foods—

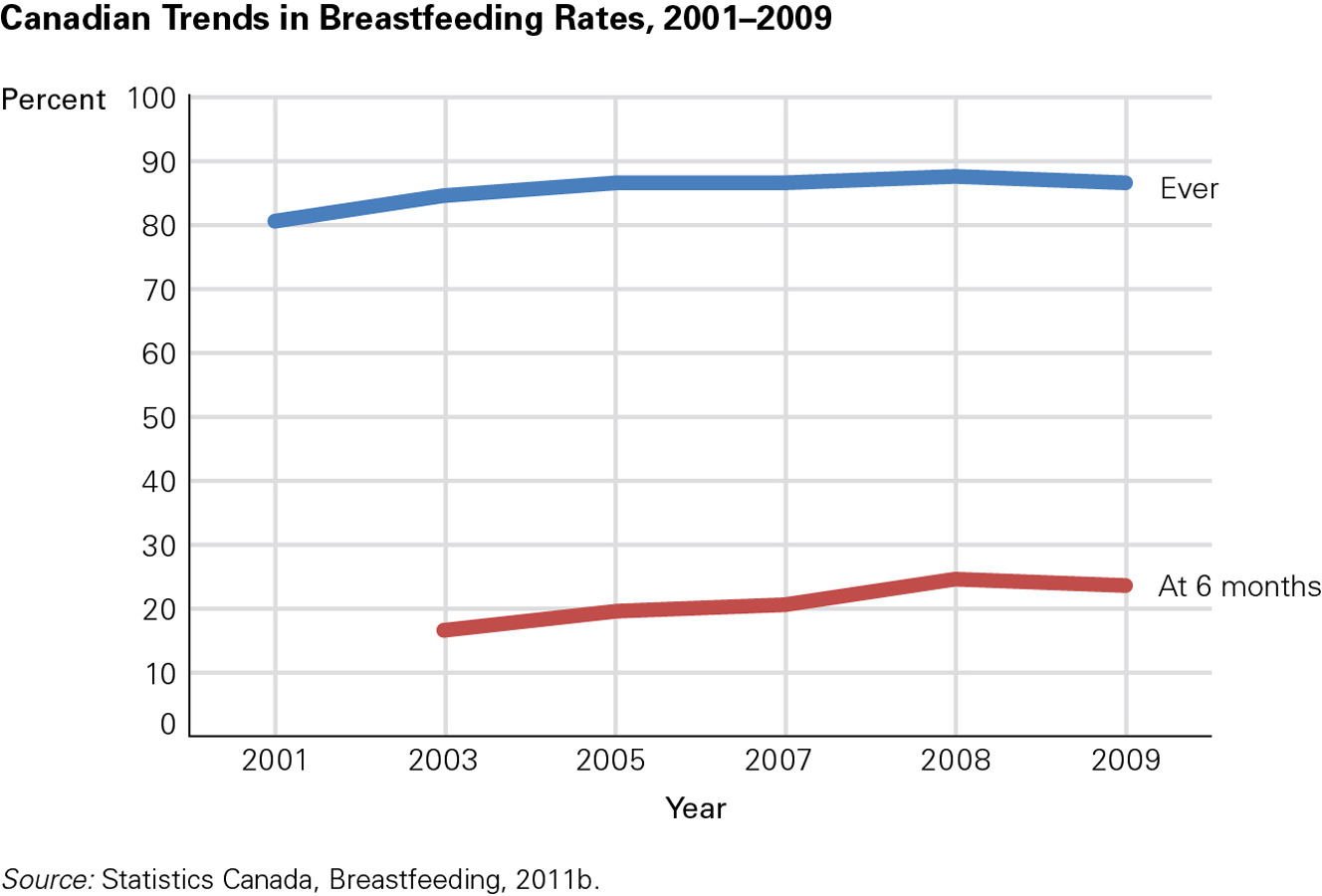

Breastfeeding was once universal, but by the middle of the twentieth century many mothers thought formula feeding was more modern. Fortunately, that has changed again. In 2005, the Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) began recommending that newborn infants be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months (Boland, 2005). By 2009, 87 percent of Canadian mothers were breastfeeding their most recent baby for at least a short period of time. In the same year, just under 25 percent of mothers were following the CPS recommendation and exclusively breastfeeding their infants for at least six months (see Figure 3.7) (Statistics Canada, 2011b).

ESPECIALLY FOR New Parents When should parents decide whether to feed their baby only by breast, only by bottle, or using some combination? When should they decide whether or not to let their baby use a pacifier?

Both decisions should be made within the first month. If parents wait until the infant is 4 months or older, they may discover that they are too late. It is difficult to introduce a bottle to a 4-month-old who has been exclusively breastfed or a pacifier to a baby who has already adapted the sucking reflex to a thumb.

114

Although statistics for breastfeeding of Aboriginal children have some serious limitations, one earlier survey found that 73 percent of off-

Worldwide, about half of all 2-

115

MalnutritionProtein-calorie malnutrition occurs when a person does not consume sufficient food to sustain normal growth. That form of malnutrition occurs for roughly one-

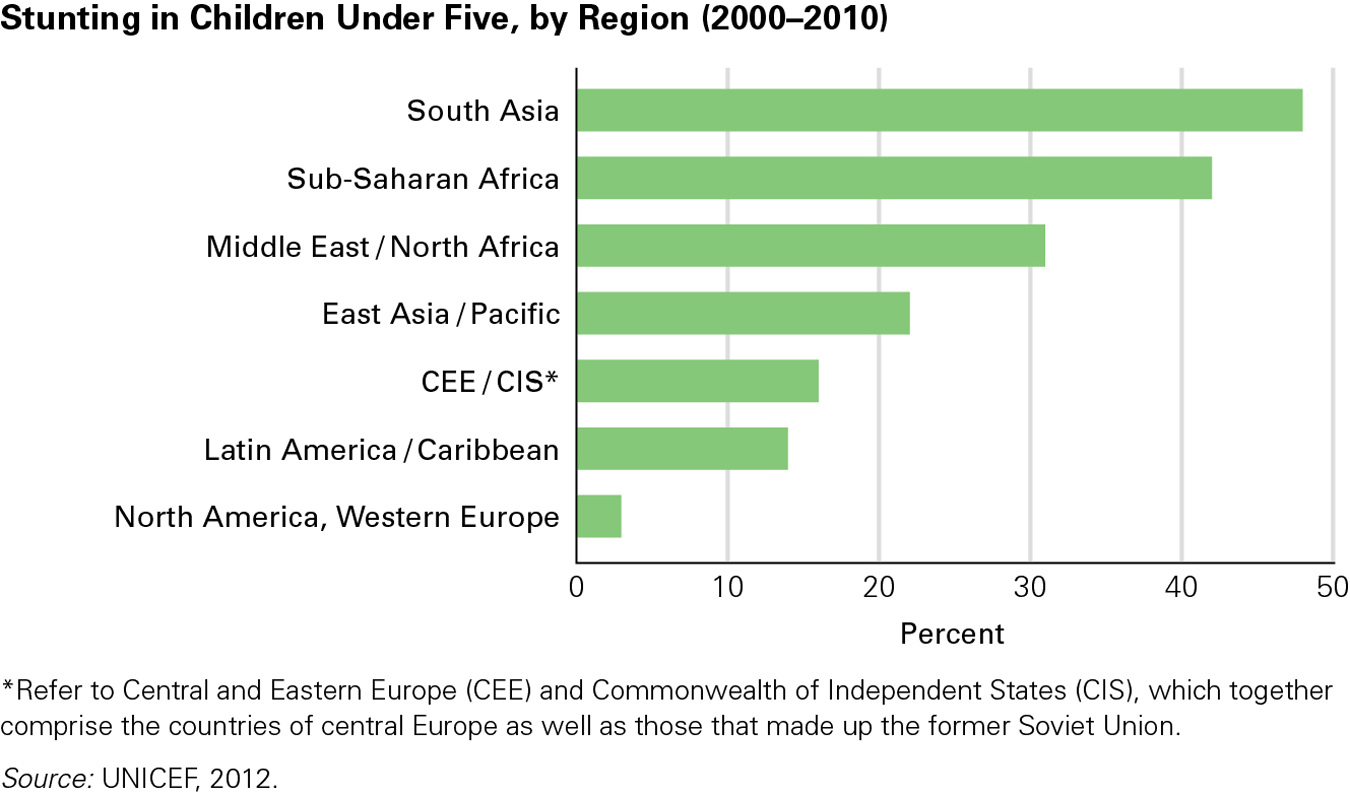

Even worse is wasting, when children are severely underweight for their age and height (two or more standard deviations below average). Many nations, especially in East Asia, Latin America, and central Europe, have seen improvement in child nutrition in the past decades, with an accompanying decrease in wasting and stunting.

In some other nations, primarily in Africa, wasting has increased. And in several nations in South Asia, about half the children over age 5 years are stunted and half of them are also wasted, at least for a year (World Bank, 2010). In terms of development, the worst effect is that energy is reduced and normal curiosity is absent (Osorio, 2011).

One common way to measure a particular child’s nutritional status is to compare weight and height with the detailed norms presented in Figures 3.1 and 3.2. For example, a sign of poor nutrition would be a long child who doesn’t weigh a lot (underfeeding) or a short child who weighs a lot (overfeeding), as compared to the norms. Remember that some children may simply be genetically small, but all children should grow rapidly in the first two years.

Chronically malnourished infants and children suffer in three ways (World Bank, 2010):

- Their brains may not develop normally. If malnutrition has continued long enough to affect height, it may also have affected the brain.

- Malnourished children have no body reserves to protect them against common diseases. About half of all childhood deaths occur because malnutrition makes a childhood disease lethal.

- Some diseases result directly from malnutrition, such as marasmus during the first year, when body tissues waste away, and kwashiorkor after age 1, when growth slows down, hair becomes thin, skin becomes splotchy, and the face, legs, and abdomen swell with fluid (edema).

116

Prevention, more than treatment, stops childhood malnutrition. In fact, some children hospitalized for marasmus or kwashiorkor die even after feeding, because their digestive systems are already failing. Prevention starts with prenatal nutrition and breastfeeding, with supplemental iron and vitamin A for mother and child.

A study of two poor African nations (Niger and Gambia) found several specific factors that reduced the likelihood of wasting and stunting: breastfeeding, both parents at home, water piped to the house, a tile (not dirt) floor, a toilet, electricity, immunization, a radio, and the mother’s secondary education (Oyekale & Oyekale, 2009). Overall, “a mother’s education is key in determining whether her children will survive their first five years of life” (United Nations, 2011).

Poverty and NutritionPoverty has strong and well-

Poor nutrition, often resulting from poverty, has been directly linked to lower scores on tests of vocabulary, reading comprehension, arithmetic, and general knowledge. Poor nutrition in infancy can also have negative impacts on a child’s physical growth and motor skill development, and it can affect a child emotionally, resulting in a withdrawn or mistrustful personality (Brown & Pollitt, 1996).

Other risk factors for children in poverty include maternal drug abuse and depression. Specifically, substance abuse by a pregnant woman can stunt the growth of neurons in her baby’s brain and lead to serious neurological disorders (Jones, 1997). Depressed mothers affect their infants’ brain development because they are less likely to provide the stimulation babies need at critical points in their growth. This can result in children who are less active and have shorter attention spans (Belle, 1990).

Finally, children living in poverty are more likely to experience the chronic and elevated levels of stress that produce the hormone cortisol, which in large doses kills brain cells. This has negative impacts on memory and emotional development and on a child’s ability to concentrate (Gunnar, 1998).

DANG NGO/ZUMA PRESS/NEWSCOM

117

KEY Points

- Various public health measures have saved billions of infants in the past half-

century, the most important being access to clean water, food, and immunizations. - Immunization not only protects those who are inoculated, it also helps stop the spread of contagious diseases (via herd immunity).

- Breast milk is the ideal infant food, improving development for decades and reducing infant malnutrition and diseases.

- Severe malnutrition stunts growth and can cause death, directly through marasmus or kwashiorkor, and indirectly through vulnerability to a variety of other diseases.

- Children from families of low socioeconomic statuses are at risk of many negative consequences, even in developed countries such as Canada.