4.3 The Development of Social Bonds

As you have already seen in this chapter, the social context has a powerful impact on development. So does the infant’s age, via brain maturation. Regarding emotional development, the baby’s age determines specific social interactions that lead to growth—

Synchrony

Early parent—

Synchrony is evident in the first three months, becoming more frequent and elaborate as the infant matures (Feldman, 2007). The adult—

In addition to careful timing, synchrony also involves rhythm and tone (Van Puyvelde et al., 2010). Metaphors for synchrony are often musical—

GUYLAIN DOYLE/LONELY PLANET/GETTY IMAGES

148

Synchrony is evident not only by direct observation, as when watching a caregiver play with an infant too young to talk, but also via computer calculation of the millisecond timing of smiles, arched eyebrows, and so on (Messinger et al., 2010). One study found that mothers who took longer to bathe, feed, and diaper their infants were also most responsive. Apparently, some parents combine caregiving with emotional play, which takes longer but also allows more synchrony.

Neglected SynchronyWhat if there is no synchrony? If no one plays with an infant, what will happen? Experiments using the still-face technique have addressed these questions (Tronick, 1989; Tronick & Weinberg, 1997). In still-

To be specific, long before they can reach out and grab, infants respond excitedly to caregiver attention by waving their arms. They are delighted if the adult moves closer so that a waving arm touches the face or, even better, a hand grabs hair. You read about this eagerness for interaction in Chapter 3, when infants try to “make interesting sights last” or when they babble in response to adult speech. Meanwhile, adults open their eyes wider, raise their eyebrows, smack their lips, and emit nonsensical sounds—

In the next phase of the experiment, on cue, the same adult does not move closer but instead erases all facial expression, staring quietly with a “still face” (a motionless face) for a minute or two. Sometimes by 2 months, and clearly by 6 months, infants are upset by still faces, especially from their parents (less so from strangers). Babies frown, fuss, drool, look away, kick, cry, or suck their fingers. By 5 months, they also vocalize, as if to say, “Pay attention to me” (Goldstein et al., 2009).

Many types of studies have reached the same conclusion: Synchrony is vital. Responsiveness aids psychosocial and biological development, evident in heart rate, weight gain, and brain maturation (Moore & Calkins, 2004; Newnham et al., 2009). Particularly in the first year, babies of depressed mothers suffer unless someone else is a sensitive partner (Bagner et al., 2010). In the following section, we examine the next stage in child—

Attachment

Toward the end of the first year, face-

British psychoanalyst and researcher John Bowlby first developed a comprehensive theory to explain attachment (1969, 1973a, 1973b, 1988). His work was carried on and expanded upon by American-

As is often the case, both Bowlby and Ainsworth grounded their work in that of other scientists, especially in the fields of psychoanalysis and ethology (the study of animals with the focus on behavioural patterns in natural environments). Bowlby was influenced by the work of psychoanalyst René Spitz (1946), who studied infants in a Colorado orphanage. Spitz tried to explain why, even though these children received adequate food and physical care, they failed to thrive. According to Freud, if basic needs are met, infants would bond with their mothers. Instead, the orphaned infants lost weight, grew passive, and showed no positive feelings for the nurse who fed them (Rutter, 2006). Spitz came to believe that the children suffered a kind of emotional deprivation from the loss of their mothers, and that this sense of loss had lasting negative impacts on their development.

149

Researcher Harry Harlow’s work also had an important influence on the development of attachment theory. In Harlow’s classic study (1958), rhesus monkeys were taken from their mothers shortly after birth and placed in a cage with two mechanical “mothers.” One was made of wire and had a feeding bottle. The other was covered in soft terrycloth and had no bottle. Surprisingly, all the infant monkeys spent much more time clinging to the cloth mother than the wire one, only going to the wire mother to feed. From this and later experiments, Harlow concluded that an infant’s love for its mother is based more on emotional needs than physical requirements such as hunger and thirst.

Bowlby used the term “maternal deprivation” to describe the emotional trauma suffered by infants who lose their mother or other beloved caregiver. He also believed that the evolutionary need for protection reinforced children’s profound attachment to their maternal or principal caregiver. “The infant and young child,” Bowlby stated in one of his early works, “should experience a warm, intimate, and continuous relationship with his mother (or permanent mother substitute) in which both find satisfaction and enjoyment” (1951). Bowlby argued that not experiencing this fundamental relationship would have serious impacts on a child’s mental health.

Although it is most evident at about age 1 year, attachment begins before birth and influences relationships throughout life (see At About This Time). Adults’ attachment to their parents, formed decades earlier, affects their behaviour with their own children as well as their relationship with their partners (Grossmann et al., 2005; Kline, 2008; Simpson & Rholes, 2010; Sroufe et al., 2005).

In recent years, research on infant attachment has looked beyond Western parenting practices; in Canada, the caregiver-

For many Aboriginal families in Canada (and elsewhere), the themes of holism, balance, and respect inform the way children are instructed in their views of health and sickness, and their relations to others (Adelson, 2007). The Medicine Wheel, for example, is one of the models that represents First Peoples’ worldview of the interactions and balance among mind, emotions, spirit, and body (Mitchell & Maracle, 2005), and the interconnectedness with all person’s relations, community, and the land (Vukic et al., 2011). So, researchers in this area need to pay attention to the history, ancestors, extended family, and community to which the caregiver and child are connected, as these connections influence parenting.

Signs of AttachmentInfants show their attachment through proximity-

150

Stages of Attachment

| Birth to 6 weeks | Preattachment. Newborns signal, via crying and body movements, that they need others. When people respond positively, the newborn is comforted and learns to seek more interaction. Newborns are also primed by brain patterns to recognize familiar voices and faces. |

| 6 weeks to 8 months | Attachment in the making. Infants respond preferentially to familiar people by smiling, laughing, babbling. Their caregivers’ voices, touch, expressions, and gestures are comforting, often overriding the infant’s impulse to cry. Trust develops. |

| 8 months to 2 years |

Classic secure attachment. Infants greet the primary caregiver, play happily when the caregiver is present, and show separation anxiety when the caregiver leaves. Both infant and caregiver seek to be close to each other (proximity) and frequently look at each other (contact). In many caregiver– |

| 2 to 6 years |

Attachment as launching pad. Young children seek their caregiver’s praise and reassurance as their social world expands. Interactive conversations and games (hide- |

| 6 to 12 years | Mutual attachment. Children seek to make their caregivers proud by learning whatever adults want them to learn, and adults reciprocate. In concrete operational thought, specific accomplishments are valued by adults and children. |

| 12 to 18 years | New attachment figures. Teenagers explore and make friendships on their own, using their working models of earlier attachments as a base. With more advanced, formal operational thinking, shared ideals and goals become more influential. |

| 18 years on | Attachment revisited. Adults develop relationships with others, especially relationships with romantic partners and their own children, influenced by earlier attachment patterns. Past insecure attachments from childhood can be repaired rather than repeated, although this does not always happen. |

| Source: Adapted from Grobman, 2008. | |

Research on attachment has occurred in dozens of nations, with people of many ages. Attachment seems to be universal, but specific manifestations vary. For instance, Ugandan mothers never kiss their infants but often massage them, contrary to Western custom. Adults who are securely attached to each other might remain in contact via daily phone calls, emails, or texts, and keep in proximity by sitting in the same room as each reads quietly. Some scholars believe that attachment, not only of mother and infant but also of fathers, grandparents, and non-

Secure and Insecure AttachmentAs infants make sense of their social world, they develop an internal working model, a cognitive framework that is comprised of mental representations for interpreting their world, self, and others. So, how the situation will be evaluated, what is expected, and what infants will do are guided by the internal working model. Simply put, Bowlby (1969) believed that their first relationship (primary caregiver) will act as the prototype for future relationships.

Mary Ainsworth first developed a way of studying Bowlby’s attachment theory by conducting experiments that identified different types of attachment that infants might have with their caregivers. Based on Ainsworth’s work, attachment is now classified into four types, A, B, C, and D (see TABLE 4.1).

| Type | Name of Pattern | In Playroom | Mother Leaves | Mother Returns | Toddlers in Category (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Insecure- |

Child plays happily. | Child continues playing. | Child ignores her. | 10– |

| B | Secure | Child plays happily. | Child pauses, is not as happy. | Child welcomes her, returns to play. | 50– |

| C | Insecure- |

Child clings, is preoccupied with mother. | Child is unhappy, may stop playing. | Child is angry; may cry, hit mother, cling. | 10– |

| D | Disorganized | Child is cautious. | Child may stare or yell; looks scared, confused. | Child acts oddly— |

5– |

151

Infants with secure attachment (B) feel comfortable and confident because their parents are generally responsive and sensitive to their needs. “Responsive” and “sensitive” are terms that need to be distinguished because they describe two different types of behaviour. If a baby cries and a parent immediately goes over to the baby to see what the matter is, this is responsive behaviour. However, does the parent know why the baby is crying? Is the baby hungry? Does the baby’s diaper need to be changed? Does the baby want to be held? That is when parents need to be sensitive to the needs of their infants (and later on, to those of their children). When parents are responsive and sensitive, infants learn that they can trust their parents to protect them and to ensure their well-

By contrast, insecure attachment (A and C) is characterized by fear, anxiety, anger, or indifference in children whose parents are not consistently sensitive or responsive to their needs. Some insecure children play independently without maintaining contact; this is insecure-avoidant attachment (A). The opposite reaction is also insecure: some children are unwilling to leave the caregiver’s lap, which is insecure-resistant/ambivalent attachment (C).

Ainsworth’s original schema identified only A, B, and C types of attachment. Later researchers discovered a fourth category (D), disorganized attachment. Type D infants may shift from hitting to kissing their mothers, from staring blankly to crying hysterically, or from pinching themselves to freezing in place.

Among the general population (not among infants with special needs), almost two-

About one-

152

Measuring AttachmentAinsworth (1973) developed a now-

- Exploration of the toys. A secure toddler plays happily.

- Reaction to the caregiver’s departure. A secure toddler notices when the caregiver leaves and shows some sign of missing him or her.

- Reaction to the caregiver’s return. A secure toddler welcomes the caregiver’s reappearance, usually seeking contact, and then plays again.

In this procedure, the infant’s behaviour in response to these situations indicates the quality or security of the child’s attachment.

Attachment is not always measured via the Strange Situation. Instead, surveys and interviews are also used. Sometimes parents answer 90 questions about their children’s characteristics, and sometimes adults are interviewed extensively (according to a detailed protocol) about their relationships with their own parents, again with various specific measurements (Fortuna & Roisman, 2008).

Research measuring attachment has revealed that some behaviours that might seem normal are, in fact, a sign of insecurity. For instance, an infant who clings to the caregiver and refuses to explore the toys in the new playroom might be type A. Likewise, adults who say their childhood was happy and their mother was a saint, especially if they provide few specific memories, might be insecure. And young children who are immediately friendly to strangers may never have formed a secure attachment (Tarullo et al., 2011). A new diagnostic category in DSM-

Assessments of attachment, developed and validated for middle-

Insecure Attachment and Social Setting

At first, developmentalists expected secure attachment to “predict all the outcomes reasonably expected from a well-

Securely attached infants are more likely to become secure toddlers, socially competent preschoolers, high-

Secure attachment (type B) is more likely if:

Insecure attachment is more likely if:

|

153

Harsh contexts, especially the stresses of poverty, reduce the incidence of secure attachment (Seifer et al., 2004; van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-

Many aspects of low SES make low school achievement, hostile children, and fearful adults more likely. The underlying premise—

Insights From RomaniaNo scholar doubts that close human relationships should develop in the first year of life and that the lack of such relationships has dire consequences. Unfortunately, thousands of children born in Romania are proof. When Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausesçu outlawed birth control and abortions in the 1980s, illegal abortions became the leading cause of death for Romanian women aged 15 to 45 (Verona, 2003), and more than 100 000 children were abandoned to crowded, impersonal, state-

In the two years after Ceausesçu was ousted and executed in 1989, thousands of those children were adopted by North American, western European, and Australian families. Those who were adopted before 6 months of age fared best; synchrony was established via play and caregiving. Most of them developed normally.

For those adopted after 6 months, and especially after 12 months, early signs were encouraging: skinny infants gained weight and grew faster than other 1-

154

These children are now young adults, many with serious emotional or conduct problems. The cause is more social than biological. Even those who were relatively well nourished at adoption, or who caught up to normal growth, often became impulsive and angry teenagers. Apparently, the stresses of adolescence and emerging adulthood exacerbated the cognitive and social strains on these children and their families (Merz & McCall, 2011).

Romanian infants are no longer available for international adoption, but some are still abandoned. Research confirms that early emotional deprivation, not genes or nutrition, is their greatest problem. Romanian infants develop best in their own families, second best in foster families, and worst in institutions (Nelson et al., 2007). To the best of our knowledge, this applies to infants everywhere: Families usually care for their babies better than strangers do.

Fortunately, institutions have improved somewhat; more recent adoptees are not as impaired as those 1990 Romanian orphans (Merz & McCall, 2011). However, some infants in every nation are still deprived of healthy interactions, and the early months seem to be a sensitive period for emotional development. Children need parents, biological or not (McCall et al., 2011).

Preventing ProblemsAll infants need love and stimulation; all seek synchrony and then attachment—

Since synchrony and attachment develop over the first year, and since more than one-

If biological parents cannot care for their newborns, foster or adoptive parents need to be found quickly so synchrony and attachment can develop (McCall et al., 2011). Sometimes children are placed in kinship care, especially with their grandparents. In Canada, provincial governments have begun to emphasize using the least intrusive form of intervention when placing a child in foster care. This means they are now providing financial support for kinship care through their foster care systems. As a result, the number of children under 18 years in Canada who were living with grandparents instead of parents increased by 20 percent from 1991 to 2001. When grandparents serve as a child’s primary caregivers, this is known as a “skipped generation household.” By 2001, there were 56 700 Canadian grandparents in skipped generation households (Fuller-

This trend is especially evident among First Nations, whose children, according to Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, are four to six times more likely than other Canadian children to come into the care of child welfare agencies (Fuller-

155

If high-

Social Referencing

Social referencing refers to infants seeking emotional responses or information from other people. You may see this when you approach a toddler and she starts looking back and forth between her parent and you. She is looking for facial and body cues from her parent to see if she should be afraid. A parent’s reassuring glance or cautionary words, a facial expression of alarm, pleasure, or dismay—

After age 1, when infants can walk and are little scientists, their need to consult others becomes urgent. Social referencing is constant, as toddlers search for clues in gazes, faces, and body position, paying close attention to emotions and intentions. They focus especially on their familiar caregivers, but they also use relatives, other children, and even strangers to help them assess objects and events. They are remarkably selective: even at 16 months, they recognize which strangers are reliable references and which are not (Poulin-

Social referencing has many practical applications. Consider mealtime. Caregivers the world over smack their lips, pretend to taste, and say “yum-

Fathers as Social Partners

Fathers enhance their children’s social and emotional development in many ways (Lamb, 2010). Synchrony, attachment, and social referencing are all apparent with fathers, sometimes even more than with mothers. This was doubted until researchers found that some infants are securely attached to their fathers but not to their mothers (Bretherton, 2010). Further, fathers elicit more smiles and laughter from their infants than mothers do.

Close father–

In some cultures and ethnic groups, fathers spend much less time with infants than mothers do (Parke & Buriel, 2006; Tudge, 2008). Culture and parental attitudes are influential: Some women believe that child care is their special domain (Gaertner et al., 2007), while some fathers think it unmanly to dote on an infant. This is not equally true everywhere. For example, Denmark has high rates of father involvement. At birth, 97 percent of Danish fathers are present, and five months later, most Danish fathers say that every day they change diapers (83 percent), feed their infants (61 percent), and play with them (98 percent) (Munck, 2009).

156

BRITTA KASHOLM-

Research on ethnic minority fathers in North America has increased in recent years, particularly on fathers in immigrant families (Chuang & Moreno, 2011; Chuang & Tamis-

To illustrate, studies on immigrant Chinese-

Less rigid sex roles seem to be developing among parents in many nations. One example of historical change is the number of married mothers with children under age 6 who are employed in Canada. The employment rate in 2009 for this population was 64.4 percent, as compared to 27.6 percent in 1976 (Statistics Canada, 2010a). Note the reference to “married” mothers: About half the mothers of infants in Canada are not married, and their employment rates are even higher. As detailed later in this chapter, often fathers—

One sex difference seems to endure: Mothers engage in more caregiving and comforting, and fathers in more high-

157

Since the 1970s, father–

- Can men provide the same care as women?

- Is father–

infant interaction different from mother– infant interaction? - How do fathers and mothers interact to provide infant care?

Many studies over the years have answered yes to the first two. On the third question, the answer depends on the family (Bretherton, 2010). Usually mothers are caregivers and fathers are playmates, but not always—

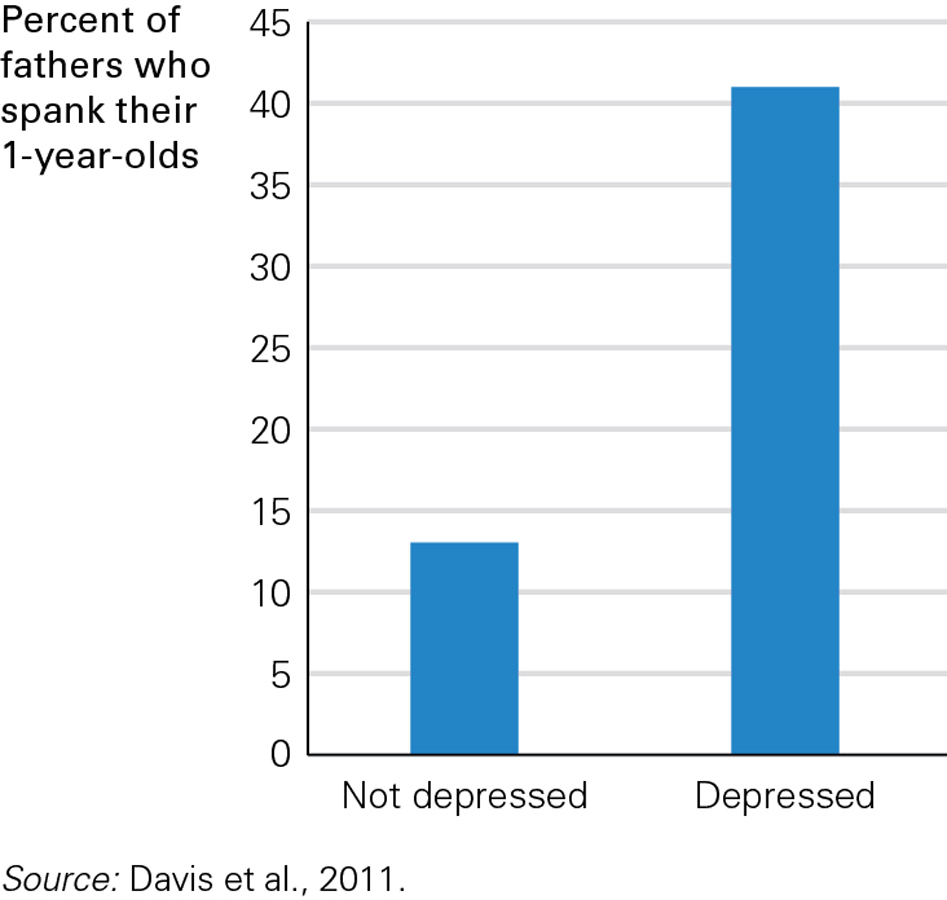

A constructive parental alliance is not guaranteed, whether or not the parents are legally wed. Sometimes neither parent is happy with their infant, with themselves, or with each other. One study reported that 7 percent of fathers of 1-

Family members are affected by each other’s moods: Paternal depression correlates with maternal depression, and with sad, angry, and disobedient toddlers. Cause and consequence are intertwined. When infants are depressed, or anxious, or hostile, the family triad (mother, father, baby) all need help.

KEY Points

- Caregivers and young infants engage in split-

second interaction, evidence of synchrony. - Attachment between people is universal, apparent in infancy with contact-

maintaining and proximity- seeking as 1- year- olds play. - Toddlers use other people as social references, to guide them in their exploration.

- Fathers are as capable as mothers in social partnerships with infants, although they may favour physical, creative play more than mothers do.