6.6 Child Maltreatment

We have reserved the most disturbing topic, child maltreatment, for the end of this chapter. The assumption throughout has been that parents and other adults seek the best for young children, and that their disagreements (e.g., what to feed them, how to discipline, what kind of early education to provide) arise from contrasting ideas about what is best.

However, the sad fact is that not everyone seeks the best for children. Sometimes parents harm their own offspring. Often the rest of society ignores the preventive and protective measures that could stop much maltreatment. Lest we become part of the problem, not part of the solution, we first need to recognize child neglect and abuse.

Maltreatment Noticed and Defined

Until about 1960, people thought child maltreatment was a rare, sudden attack by a disturbed stranger. Today we know better, thanks to a pioneering study based on careful observation of the “battered child syndrome” in one Boston hospital (Kempe & Kempe, 1978). Maltreatment is neither rare nor sudden, and the perpetrators are usually one or both of the child’s parents. In these instances, maltreatment is often ongoing, and the child has no protector, which may make the maltreatment more damaging than a single incident, however injurious.

With this recognition came a broader definition: Child maltreatment now refers to all intentional harm to, or avoidable endangerment of, anyone under 18 years of age. Thus, child maltreatment includes both child abuse, which is deliberate action that is harmful to a child’s physical, emotional, or sexual well-

Frequency of Maltreatment

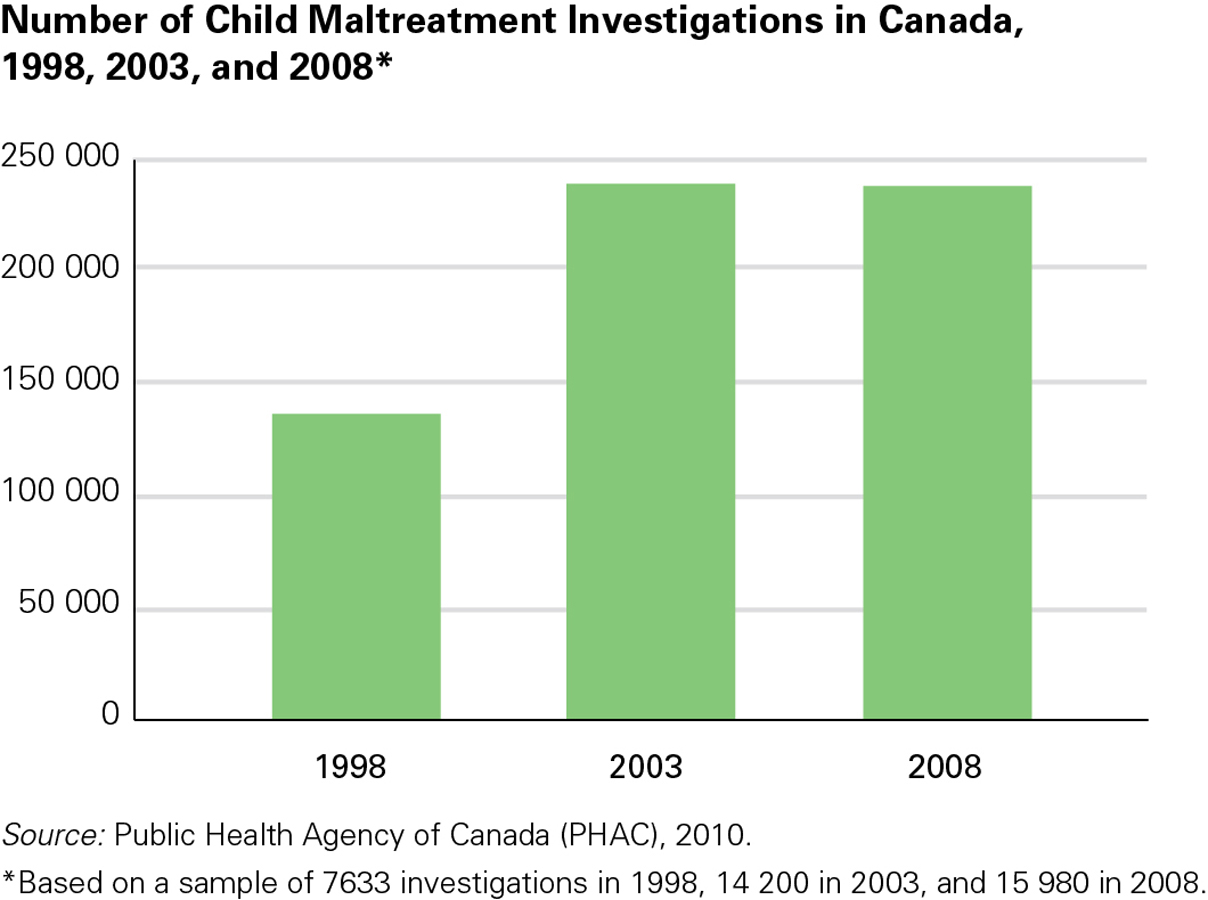

How common is maltreatment? No one knows. Not all cases are noticed; not all noted cases are reported and not all reports are substantiated. The number of investigations for reported cases of child maltreatment in Canada rose sharply in the five-

OBSERVATION QUIZ

How would you explain the changes in rates of maltreatment-

Changes in rates might be due to changes in awareness of the problem, in legislation, in definitions of the problem, and/or in the actual rate of maltreatment.

How maltreatment is defined by legislation and the level of public and professional awareness of the problem can influence the level of reporting. For example, the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect reported that the average annual caseload in 2008 varied among provinces and territories. Based on the child population of 15 years or younger, the territories together had the highest level of reporting (11.67 percent), with British Columbia having the second highest rate (4 percent). The Atlantic provinces had the lowest level of reporting, at 1.54 percent. Generally, Aboriginal children were at greater risk of maltreatment (18 percent) as compared to their non-

240

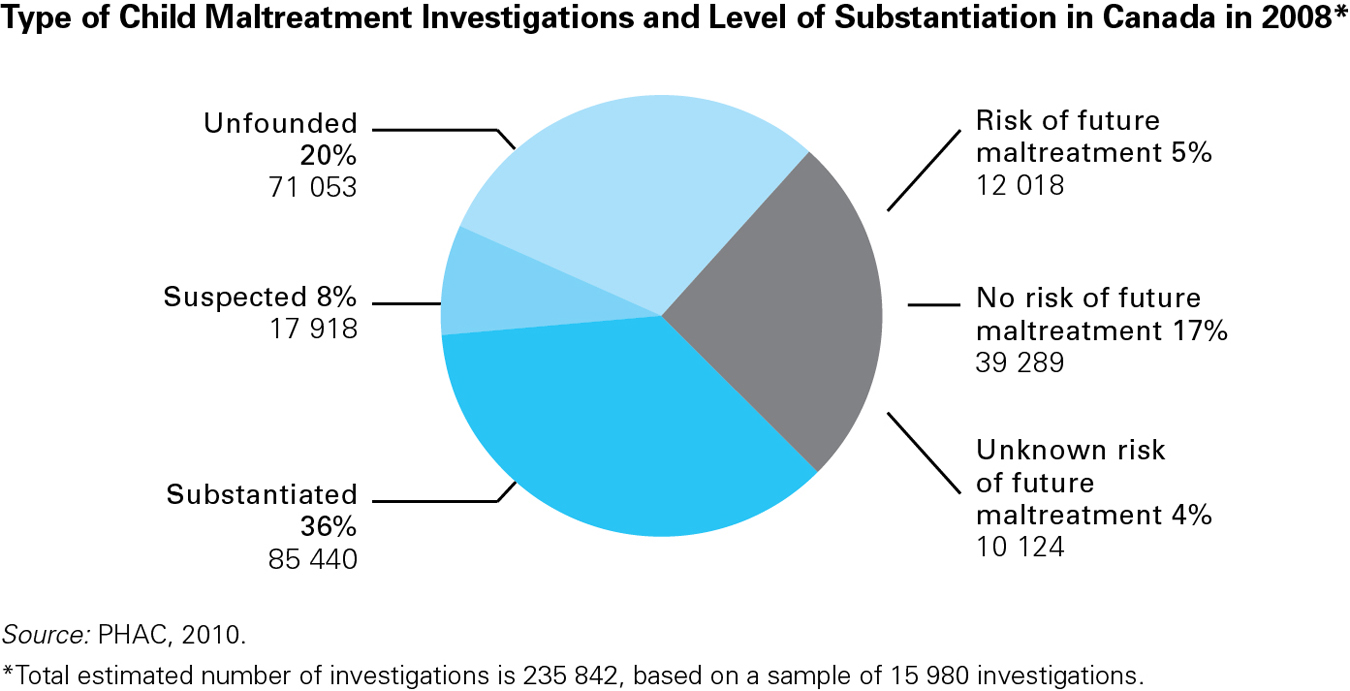

The number of substantiated victims is much lower than the number of reported victims primarily because the same child is often reported several times, leading to one substantiated case. Also, substantiation requires proof—

Often the first sign of maltreatment is delayed development, such as slow growth, immature communication, lack of curiosity, or unusual social interactions. Anyone familiar with child development can observe a young child and notice such problems. Maltreated children often seem fearful, startled by noise, defensive and quick to attack, and confused between fantasy and reality. TABLE 6.3 lists signs of child maltreatment, both neglect and abuse. None of these signs are proof that a child has been abused, but whenever any of them occurs, it signifies trouble.

| Injuries that do not fit an “accidental” explanation, such as bruises on both sides of the face or body; burns with a clear line between burned and unburned skin; “falls” that result in cuts, not scrapes Repeated injuries, especially broken bones not properly tended (visible on X- Fantasy play, with dominant themes of violence or sexual knowledge Slow physical growth, especially with unusual appetite or lack of appetite Ongoing physical complaints, such as stomach aches, headaches, genital pain, sleepiness Reluctance to talk, to play, or to move, especially if development is slow No close friendships; hostility toward others; bullying of smaller children Hypervigilance, with quick, impulsive reactions, such as cringing, startling, or hitting Frequent absence from school Frequent changes of address Turnover in caregivers who pick up child, or caregiver who comes late, seems high Expressions of fear rather than joy on seeing the caregiver |

ESPECIALLY FOR Nurses While weighing a 4-

Any suspicion of child maltreatment must be reported, and these bruises are suspicious. Someone in authority must find out what is happening so that the parent as well as the child can be helped.

Noticing children who are maltreated is only part of the task; we also need to notice the conditions and contexts that make abuse or neglect more likely (Daro, 2009). Poverty, social isolation, and inadequate support (public and private) for caregivers are among them. From a developmental perspective, immaturity of the caregiver is a risk factor: Maltreatment is more common if parents are younger than 20 or if families have several children under age 6.

Consequences of Maltreatment

The impact of any child-

Although culture is always relevant, as more longitudinal research is published, the effects of maltreatment are proving to be devastating and long lasting. The physical and academic impairment from maltreatment is relatively easy to notice—

241

Child neglect is three times more common than overt abuse. Research shows that children who were neglected experience even greater social deficits than abused ones because they were unable to relate to anyone, even in infancy (Stevenson, 2007). The best cure for a mistreated child is a warm and enduring friendship, but maltreatment makes this unlikely.

Adults who were severely maltreated (physically sexually or emotionally) often engage in self-

Finding and keeping a job is a critical aspect of adult well-

242

Three Levels of Prevention, Revisited

Just as with injury control, there are three levels of prevention of maltreatment. The ultimate goal is primary prevention, which focuses on the macrosystem and exosystem. Examples of primary prevention include increasing stable neighbourhoods and family cohesion, and decreasing financial instability, family isolation, and adolescent parenthood.

Secondary prevention involves spotting warning signs and intervening to keep a risky situation from getting worse (Giardino & Alexander, 2011). For example, insecure attachment, especially of the disorganized type (described in Chapter 4), is a sign of a disrupted parent–

Tertiary prevention includes everything that limits harm after maltreatment has already occurred. Reporting and substantiating abuse are only the first steps. Often the caregiver needs help to provide better care. Sometimes the child needs another home. If hospitalization is required, that signifies failure: Intervention should have begun much earlier. At that point, treatment is very expensive, harm has already been done, and hospitalization itself further strains the parent–

Children need caregivers they trust, in safe and stable homes, whether they live with their biological parents, a foster family, or an adoptive family. Whenever a child is legally removed from an abusive or neglectful home and placed in foster care, permanency planning must begin, to find a family to nurture the child until adulthood. Permanency planning is a complex task. Parents are reluctant to give up their rights to the child; foster parents hesitate to take a child who is hostile and frightened; maltreated children need intensive medical and psychological help but foster care agencies are slow to pay for such services.

The most common type of foster care in North America is kinship care (see Chapter 4), in which a relative (most often the grandmother) takes over child-

One tragic case in point involved a young First Nations boy from Norway House in Manitoba. Jordan River Anderson was born with a rare muscular disorder that meant he had very complex medical needs. Realizing they couldn’t care for him themselves, Jordan’s parents placed him with a child welfare agency shortly after his birth, and he was immediately admitted into a Winnipeg hospital. In the meantime, his family and the welfare agency worked to find him a foster home that could meet both his medical needs and give him the benefits of growing up in a positive family environment.

243

Shortly after his second birthday, the doctors were ready to release Jordan from hospital, but at that point the provincial and federal governments, who share jurisdiction for First Nations people, began a dispute over who should pay for Jordan’s foster care. The dispute dragged on for more than two years as officials argued over the cost of installing a special ramp and the price of a showerhead. Shortly after Jordan’s fifth birthday, he accidently pulled out his breathing tube and died in hospital (Lavallee, 2005).

This tragedy led to the establishment of Jordan’s Principle, a measure meant to resolve jurisdictional disputes between the federal and provincial/territorial governments that involve services provided to First Nations children. Under this principle, whenever a dispute arises between two levels of government or between two departments of the same government over which should pay for services for a First Nations child, the government or department of first contact is required to pay until the dispute has been resolved. Under a private member’s motion, Jordan’s Principle was unanimously supported by the House of Commons in 2007 (Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, 2013).

As detailed many times in this chapter, caring for young children—

KEY Points

- The source of child maltreatment is often the family system and the cultural context, not a disturbed stranger.

- Child maltreatment includes both abuse and neglect, with neglect more common and perhaps more destructive.

- Maltreatment can have long-

term effects on cognitive and social development, depending partly on the child’s personality and on cultural values. - Prevention can be primary (laws and practices that protect everyone), secondary (protective measures for high-

risk situations), and tertiary (reduction of harm after maltreatment has occurred).