The Aging Brain

As just explained, superficial changes in appearance need not be devastating, diseases usually are not fatal until old age, and sex can be satisfying throughout adulthood. However, decline in brain functioning cannot be so easily dismissed. Descartes famously said, “I think, therefore I am.” Loss of brain power is equated with loss of self. Is that what adulthood brings?

Pathological Changes

Video: Brain Development Animation: Middle Adulthood

Like every other part of the body, the brain slows down with age. Neurons take longer to fire, and messages sent from the axon of one neuron are not picked up as quickly by the dendrites of other neurons. Reaction time lengthens.

However, major neurocognitive disorder (formerly called dementia), when thinking is so erratic or memory so impaired that normal life is impossible, rarely occurs until after age 70 or so—

For most adults under age 65, brain changes do not correlate with intellectual depth (Greenwood & Parasuraman, 2012). To use a metaphor, adult brains cannot sprint but they can run a marathon—

A leading researcher on adult intellect wrote, “Decline prior to 60 years of age is almost inevitably a symptom or precursor of pathological age changes” (Schaie, 2005/2013, p. 497). Pathological means disease-

Drug abuse. All psychoactive drugs harm the brain, especially prolonged, excessive use of alcohol, which can cause Wernicke-

Korsakoff syndrome (“wet brain”). Poor circulation. Everything that impairs blood flow—

such as hypertension (high blood pressure) and heavy cigarette smoking— also impairs cognition. Viruses. The blood–

brain barrier keeps most viruses away, but a few— including HIV and the prion that causes mad cow disease— can destroy neurons. Genes. About 1 in 1,000 people inherits a dominant gene for Alzheimer’s disease, which destroys memory. Other uncommon genes also affect the brain.

Intelligence in Adulthood

Video Activity: Research Methods and Cognitive Aging explores how various research methods have been employed to study how intelligence changes with age.

Brains and intelligence vary as much as humans do. Intellectual abilities can rise, fall, zigzag, or stay the same, depending on genes and on the specifics of each life. This again illustrates the life-

You read in Chapter 7 that IQ correlates with school achievement in childhood. But what about achievement over the years of adulthood?

general intelligence (g)

The idea that intelligence is one basic trait, underlying all cognitive abilities. According to this concept, people have varying levels of this general ability.

One leading theoretician, Charles Spearman (1927), proposed that there is a single entity that he called general intelligence (g), which each adult has to some degree. Although g cannot be measured directly, it can be inferred from various abilities, such as vocabulary, memory, and reasoning. Measuring those abilities produces an IQ score. That score correlates with health and wealth in adulthood.

Once a person reaches adulthood, an IQ score indicates whether that adult is a genius, average, or slow, no matter what the person’s age. As you remember, in childhood, a person’s score depends not only on items correct, with different items for preschoolers and older children, but also on the child’s age. That it not true for adults. The same IQ tests are usually given to people aged 18 to 88, and they are scored the same way.

Question 12.23

OBSERVATION QUIZ

In addition to intellectual ability, what two aspects of this test situation might affect older men differently than younger ones?

Older adults might be more stressed by the proctors, and might find it uncomfortable to sit on the floor while writing.

The belief that g exists still influences thinking and testing on intelligence. Many neuroscientists seek genetic underpinnings for the intellect. Efforts to find specific genes or abilities that comprise g have not succeeded (Deary et al., 2010; Haier et al., 2009), but some aspects of brain function, particularly in the prefrontal cortex, hold promise (Barbey et al., 2013; Roca et al., 2010). Other scientists believe that g may arise from prenatal brain development, experiences in infancy, or physical health.

Still others question whether a single entity, g, exists. They emphasize the role of experience, noting that national and ethnic differences in average IQ scores suggest that context is crucial. Some aspects of this controversy were explored by a famous researcher, K. Warner Schaie, as the following explains.

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Adult IQ

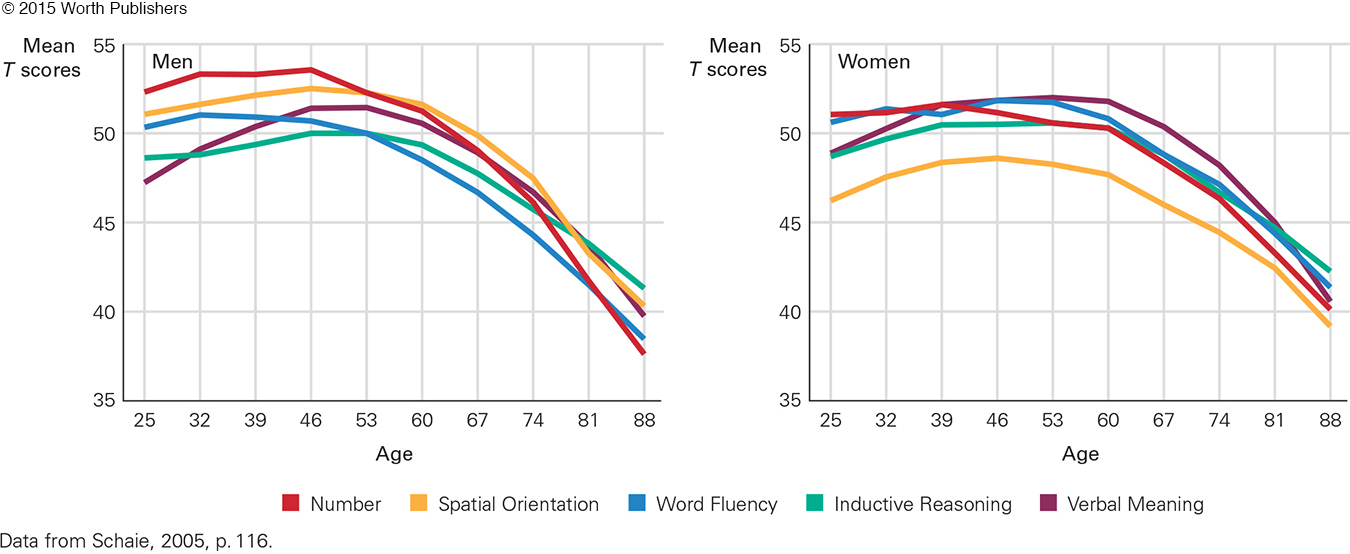

At the University of Washington in 1956, K. Warner Schaie tested a cross section of 500 adults, aged 20 to 50, on five standard primary mental abilities considered to be the foundation of intelligence: (1) verbal meaning (vocabulary), (2) spatial orientation, (3) inductive reasoning, (4) number ability, and (5) word fluency (rapid verbal associations).

His cross-

As mentioned briefly in Chapter 1, Schaie then had a brilliant idea, to combine longitudinal and cross-

Seattle Longitudinal Study

The first cross-

Schaie did so over his entire career, retesting and adding a new group every seven years. Known as the Seattle Longitudinal Study, this was the first cross-sequential study of adult intelligence. Schaie confirmed and extended what others had found: Cross-

As Figure 12.6 shows, Schaie found that each ability at each age has a distinct pattern. Men are initially better at number skills and women at verbal skills, but the two sexes grow closer over time.

You can see that some abilities increase over the years of adulthood. As many other scientists have found, vocabulary is particularly likely to increase. Schaie found that everyone declined by age 60 in at least one of their basic abilities, but not until age 88 did everyone decline from their own earlier scores in all five skills.

Other researchers from many nations find similar trends, although specifics differ (Hunt, 2011). IQ scores typically increase, or are at least maintained, in adulthood. Individuals may show marked intellectual ups or downs year by year. Some people and some abilities fall by middle age, but others not until decades later (W. Johnson et al., 2014; Kremen et al., 2014). Such marked individual variation is one argument against g.

Schaie confirmed the Flynn effect (mentioned in Chapter 7): IQ rises when nations improve childhood nutrition and education. He also discovered more detailed cohort changes than had been recognized before.

Each successive cohort (born at seven-

School curricula influenced these differences: By the mid-

Other cohort effects are that women have increased in IQ since they entered the labor market, and age-

Many studies using sophisticated designs and statistics have supplanted early cross-

Schaie found “virtually every possible permutation of individual profiles” (Schaie, 2005/2013, p. 497) of intelligence over adulthood. Although average scores on subtests decline, especially on timed tests, overall intellectual ability is usually maintained. Nature and nurture interact—

Components of Intelligence: Many and Varied

Developmentalists study patterns of cognitive gain and loss. They contend that, because virtually every pattern is possible, it is misleading to ask whether adult intelligence either increases or decreases; it does not move in lockstep. “Vast domains of cognitive performance . . . may not follow a common, age-

Consequently, many researchers focus on specific intellectual abilities, finding that each component has its own pattern. One proposal, Howard Gardner’s multiple intelligences, was described in Chapter 7. Here we consider two more: One that posits two distinct abilities and another that posits three.

TWO CLUSTERS OF INTELLIGENCE Broadly speaking, tests of intellectual abilities can be sorted into two clusters, those that measure raw learning potential and those that measure accumulated knowledge. The first group is called fluid and the second, crystallized.

fluid intelligence

Those aspects of basic intelligence that make learning of all sorts quick and thorough. Short-

As its name implies, fluid intelligence is like water, flowing to its own level no matter where it happens to be. Fluid intelligence is quick and flexible, enabling people to learn anything, even abstractions that are neither familiar nor connected to what they already know. Curiosity, learning for the joy of it, solving puzzles, and the thrill at discovering something new are marks of fluid intelligence (Silvia & Sanders, 2010).

The kinds of questions that test fluid intelligence among Western adults might be:

Question 12.24

What comes next in each of these two series?

4 9 1 6 2 5 3

V X Z B D

The correct answers are 6 and F. The clue is to think of multiplication (squares) and the alphabet; some series are much more difficult to complete.

Puzzles are often used to measure fluid intelligence, with speedy solutions given bonus points (as on many IQ tests). Immediate recall—

Since fluid intelligence appears to be disconnected from past learning, it may seem impractical. Not so. A study of adults aged 34 to 83 found that people high in fluid intelligence were more exposed to stress but were less likely to suffer from it. They used their intellect to turn stresses into positive experiences (Stawski et al., 2010).

The ability to detoxify stress may be one reason that high fluid intelligence in emerging adulthood leads to longer life and higher IQ later on. Fluid intelligence is associated with openness to new experiences and overall brain health (Batterham et al., 2009; Silvia & Sanders, 2010).

crystallized intelligence

Those aspects of intellectual ability that reflect accumulated learning. Vocabulary and general information are examples. Crystallized intelligence increases with age, while fluid intelligence declines.

By contrast, facts, information, and knowledge as a result of education and experience comprise crystallized intelligence. The size of a person’s vocabulary, the knowledge of chemical formulas, and the long-

Question 12.25

What does eleemosynary mean?

A charitable institution or donation

Question 12.26

Who was Descartes?

A 17th-

Question 12.27

Explain the difference between a tangent and a triangle.

A triangle is three lines that enclose a shape; a tangent is a line that touches a curve

Question 12.28

Why does the city of Peking no longer exist?

Peking has been renamed Beijing, the capital city of China

Although such questions seem to measure achievement more than aptitude, these two are connected, especially in adulthood. Intelligent adults read widely, think deeply, and remember what they learn, so achievement reflects aptitude. Thus, crystallized intelligence is an outgrowth of fluid intelligence (Nisbett et al., 2012).

Vocabulary, for example, improves with reading. Using the words joy, ecstasy, bliss, and delight—each appropriately, with distinct nuances (quite apart from the drugs, perfumes, or yogurts that use these names)—is a sign of intelligence. Remember the knowledge base (Chapter 7): As people know more, they learn more. That explains why a person’s years of education are considered a rough indicator of adult IQ (Nisbett et al., 2012).

To know the whole of a person’s intelligence, both fluid and crystallized intelligence must be measured. Age complicates the IQ calculation because scores on items measuring fluid intelligence decrease with age, whereas scores on crystallized intelligence increase.

Thus total IQ is often fairly steady from ages 30 to 70. Although brain slowdown begins early in adulthood, it is rarely apparent until massive declines in fluid intelligence affect crystallized intelligence. Only then do overall IQ scores fall.

This suggests that it is foolish to try to find g, a single omnibus intelligence, because components need to be measured separately. In testing for g, real developmental changes will be masked because fluid and crystallized abilities cancel each other out.

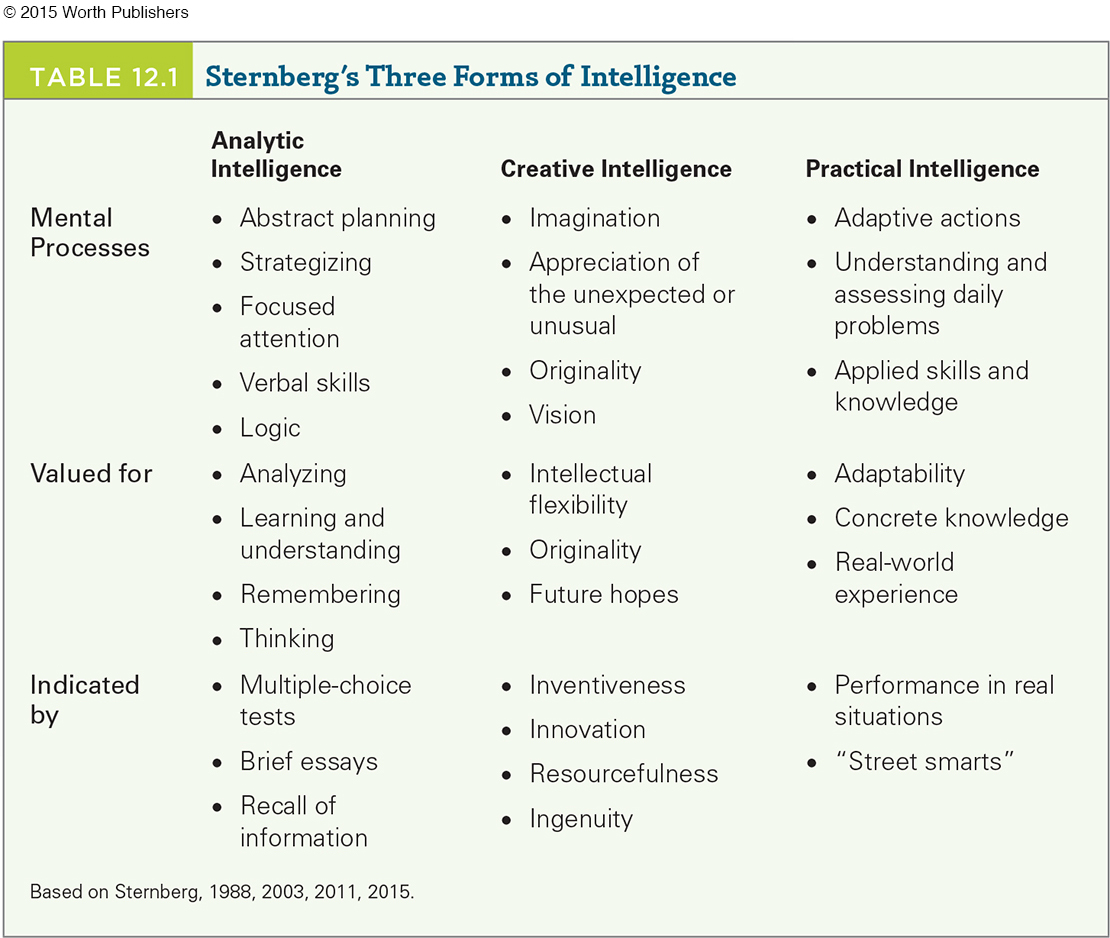

THREE FORMS OF INTELLIGENCE: STERNBERG Robert Sternberg (1988, 2003, 2011, 2015) agrees that a single intelligence score is misleading. He believes that successful intelligence is not simply the ability to do well in school (the focus of early IQ tests) but the ability to adapt to various cultural contexts, learning from experience (Sternberg, 2015).

Obviously, the years of adulthood bring many experiences, which provide opportunities for intelligence to grow. Sternberg proposed three fundamental intelligences: analytic, creative, and practical, each of which can be tested (see Table 12.1).

analytic intelligence

Intelligence that involves logic, planning, strategy selection, focused attention, and information processing.

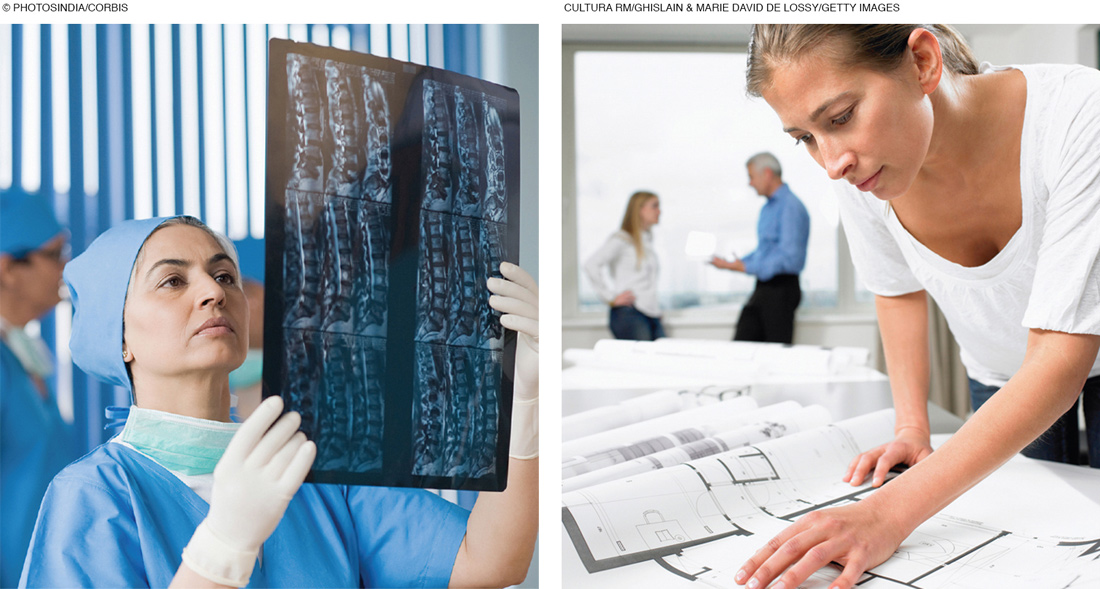

Analytic intelligence includes all the mental processes that foster academic proficiency by making efficient learning, remembering, and thinking possible. Analytic strengths are valuable in emerging adulthood, particularly in college, in graduate school, and in job training. Multiple-

creative intelligence

Intelligence that involves the capacity to be flexible and innovative, thinking unusual ideas.

Creative intelligence involves intellectual flexibility and innovation. Creative thinking is divergent rather than convergent, valuing the unexpected, imaginative, and unusual rather than standard and conventional answers. Sternberg developed tests of creative intelligence that include writing a short story titled “The Octopus’s Sneakers” or planning an advertising campaign for a new doorknob. Those with many unusual ideas earn high scores.

practical intelligence

The intellectual skills used in everyday problem solving. (Sometimes called tacit intelligence.)

Practical intelligence involves adapting to the demands of a given situation, including understanding the expectations and needs of other people. This form of intelligence is particularly needed in adulthood.

Sternberg emphasizes that everyone should deploy the strengths and guard against the limitations of each type of intelligence. Choosing which intelligence to use takes wisdom, which Sternberg considers a fourth ingredient of successful intelligence:

One needs creativity to generate novel ideas, analytical intelligence to ascertain whether they are good ideas, practical intelligence to implement the ideas and persuade others of their value, and wisdom to ensure that the ideas help reach a common good.

[Sternberg, 2012, p. 21]

INTELLIGENCE IN DAILY LIFE Practical intelligence is sometimes called tacit intelligence because it is not obvious on tests. Instead it comes from “the school of hard knocks” and may be “street smarts,” not “book smarts.” Experience advances practical intelligence, and thus adults who are able to learn from their past may gain in practical intelligence every year.

The benefits of practical intelligence in adult life are obvious. Few adults need to define obscure words or deduce the next element in a number sequence (analytic intelligence); and few need to compose new music, restructure local government, or invent a useful gadget (creative intelligence). Ideally, those few have already found a niche for themselves and rely on people with practical intelligence to implement their analytic or creative ideas.

Almost every adult, however, must solve real-

Without practical intelligence, analytic intelligence in adulthood is ineffective because people resist academic brilliance as unrealistic and elite, as the term ivory tower implies. Similarly, a stunningly creative idea may be rejected as ridiculous and weird rather than seriously considered—

For example, imagine a business manager, or a school principal, or a political leader, or a parent without practical intelligence trying to change routine practices. Some routines should be changed, of course, but that does not mean that they will be.

Perhaps that manager, principal, leader, or parent used analytic intelligence to determine that the old way was destructive and then used creative intelligence to find a better way. But practical intelligence is essential. If innovation does not take into account human views and needs, then the workers, teachers, voters, or family members may resist, misinterpret, and predict failure. The innovator would be frustrated; the people stuck to their old ways.

No abstract test can assess practical intelligence because context is crucial. Instead, adults need to be observed coping with daily life. In hiring a new employee, the interviewer might describe an actual situation and ask how the applicant would handle it. Many companies use such situational tests to hire managers. The prospective employee may be asked:

You assign a new project to one of your subordinates, who protests, saying it cannot be done without more resources and time. Rank your possible responses, from best to worst. Explain your reasoning.

You find someone else to do the job.

You ask your subordinate to figure out how it can be done with current constraints.

You reallocate work, to give your subordinate more time.

You fire the subordinate.

You ask your supervisor what to do.

You postpone the new task until you find more resources.

(from Salter & Highhouse, 2009)

Situational tests are used so often in the medical professions that review books have been made available for those preparing for such exams (e.g., Varian & Cartwright, 2013). Because practical intelligence is crucial on the job, probationary periods, internships, apprentices, and so on are common.

LEARNING IN NATIONS Difficult as it is to determine which adults are truly intelligent, it is even more difficult to judge nations, in part because each culture has its own concept of intelligence based partly on tradition and partly on current needs. Earl Hunt, a psychologist who studies intelligence, contends that the nations with the most advanced economies and greatest national wealth are those that make the best use of cognitive artifacts—that is, ways to amplify and extend general cognitive ability (Hunt, 2012).

cognitive artifacts

Intellectual tools, such as writing, invented by one generation and then passed down from generation to generation to foster learning within societies.

Historically, written language, the number system, universities, and the scientific method were cognitive artifacts. Each of these artifacts extended human intellectual abilities by helping people interact to learn more.

Sheer survival (in earlier centuries, more newborns died than lived) and longer life (few people survived past age 65) resulted from cognitive artifacts. One example is the germ theory of disease, a cognitive artifact developed from other artifacts such as the scientific method that enabled doctors to do research and learn from each other (Hunt, 2011).

In more recent times, universal education, immunization, clean water, electricity, global travel, and the Internet have resulted in advanced societies. According to this idea, smart people are better able to use the cognitive artifacts of their society to advance their own intelligence. Then they develop more cognitive artifacts, and the whole community benefits.

For instance, most developed nations provide free preschool and kindergarten to all children. That increases learning in the young, eventually advancing the nation. By contrast, other nations value fertility more than health, choose profit instead of education, educate one gender more than the other, and forbid some expressions of knowledge. That undercuts intellectual development (Hunt, 2011).

THINK CRITICALLY: If an adult lived in another nation, would he or she be smarter? And, because of that, would that adult live longer and healthier?

A recent meta-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 12.29

1. How is the brain affected by aging during adulthood?

Like every other part of the body, the brain slows down with age. Neurons take longer to fire, and messages sent from the axon of one neuron are not picked up as quickly by the dendrites of other neurons. Reaction time lengthens.

Question 12.30

2. How successful have neuroscientists been in finding g?

Many neuroscientists search for genetic underpinnings of intellectual capacity, although they have not yet succeeded in finding g. Some aspects of brain function, particularly in the prefrontal cortex, hold promise. Many other scientists also seek one common factor that undergirds IQ—

Question 12.31

3. What are the age-

Crystallized intelligence increases with age, while fluid intelligence declines.

Question 12.32

4. Why would someone want greater crystallized intelligence than fluid intelligence?

Crystallized intelligence is the accumulation of facts, information, and knowledge as a result of education and experience. Intelligent adults read widely, think deeply, and remember what they learn, so their achievement reflects their aptitude. Greater vocabulary, knowledge base, and memory for important facts are all extremely important for practical intelligence.

Question 12.33

5. Why would someone want greater fluid intelligence than crystallized intelligence?

Fluid intelligence is quick and flexible, allowing people to learn anything, even things that are unfamiliar and unconnected to what they already know. People high in fluid intelligence can draw inferences, understand relationships between concepts, and readily process new ideas and facts in part because their working memory is large and flexible.

Question 12.34

6. When would analytic intelligence be particularly useful?

Analytic strengths are valuable in emerging adulthood, particularly in college, in graduate school, and in job training.

Question 12.35

7. Would you like to be an adult high in one of Sternberg’s three intelligences but low in the other two? Why or why not?

Answers will vary.

Question 12.36

8. How might cognitive artifacts affect the economic wealth of a nation?

Educated people are better able to use the cognitive artifacts of their society to advance their own intelligence. Then they develop more cognitive artifacts, and the whole community benefits. For instance, most developed nations provide free preschool and kindergarten to all children. That increases learning in the young, eventually advancing the nation.