Selecting and Protecting

Aging neurons, cultural pressures, historical conditions, and past education all affect adult cognition. None of these can be controlled directly by an individual. Nonetheless, many researchers believe that each adult has the power to make crucial choices about his or her intellectual development.

For example, if adults decided to discard their calculators, their math skills might improve. Of course, most adults would consider that strange: Spending more time on math might help number intelligence, but few modern adults want to do double-

Similarly, memory would improve if a person never relied on their smart phone or e-

A theme of the first half of this chapter is that choices and perceptions affect adult health. That applies to intellectual development as well. As you have seen, adult IQ is variable, sometimes increasing and sometimes falling. We now look at some factors that influence this, a combination of individual choices and social pressures.

Stressors and Thought

Video Activity: The Effects of Psychological Stress outlines the explanations for and causes of stress, and then it allows you to evaluate the stress in your own life.

Many health decisions that adults make, as seen earlier in this chapter, prioritize immediate comfort over long-

Moreover, harmful choices increase stress, which impairs brain functioning (Prenderville et al., 2015). Stress does not merely correlate with illness of all kinds—

Sometimes people are told “it’s all in your head” when they complain of physical ailments. That is neither fair nor accurate. A recent comparison between stress-

Chronic stress increases depression and other psychological illnesses that impair thinking, and it attacks the brain itself (Marin et al., 2011; McEwen & Gianaros, 2011). The psychological disorder posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is recognized as harming a person long after an initial trauma. Avoiding all stress is impossible, but people can choose to reduce stress, reinterpreting problems that arise, and to care for themselves so that coping is easier.

stressor

Any situation, event, experience, or other stimulus that causes a person to feel stressed. Many circumstances become stressors for some people but not for others.

THE STRESS OF MODERN LIFE All the demands of modern life increase the stress on each adult. Some of those stresses become stressors. A stressor is an experience, circumstance, or condition that affects a person. Thus, a stress is external; some stresses are internalized, becoming stressors.

Drug abuse, obesity, lack of exercise, cigarette smoking, high-

Perhaps adults must cope with more stressors than was true earlier, although certainly some stresses are reduced. Deaths in war and revenge for crimes are decreasing (Pinker, 2011), so fewer people must cope with a premature death of a parent or child. However, the rate and scope of disasters—

To be specific, the World Health Organization defines disasters as unexpected events—

Moreover, globalization and high-

In addition, personal events that are stressful—

COPING Throughout history adults have used various ways to cope with stress. Some of these are effective; others are not.

avoidant coping

Responding to a stressor by ignoring, forgetting, or hiding it.

The worst coping is avoidant coping, which averts dealing with the problem. All the bad habits described earlier in the chapter—

Avoidant reactions cause yet more stressors. An effective way to gain perspective on stress is to help other people, yet some people in avoidant coping isolate themselves. For instance, parents of disabled children need help from each other and from relatives, but such parents have higher rates of divorce than the average parent. Similarly, some people diagnosed with serious illness do not tell their friends, some LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning) individuals stay “in the closet,” some people with serious addictions hide from other people.

problem-

A strategy to deal with stress by tackling a stressful situation directly.

emotion-

A strategy to deal with stress by changing feelings and interpretations about the stressor rather than changing the stressor itself.

Psychologists distinguish two positive strategies. In problem-

Of course, natural disasters, such as earthquakes, and personal tragedies, such as the death of a loved one, are always stressful immediately and cannot be erased. However, reinterpretation may be possible. Instead of dwelling on their misfortune, they emphasize their good fortune—

For example, although Hurricane Katrina occurred years ago, survivors continue to cope with the aftermath, and social scientists continue to study them. One team considered religious beliefs before and after the disaster. Victims who believed in a vengeful and punishing God continued to suffer, but those who believed that God is caring and benevolent coped well, experiencing posttraumatic growth, not PTSD (posttraumatic stress disorder) (Chan & Rhodes, 2013).

This study confirms a general trend. Some people use religion to cope with stress, especially when unexpected illness or disaster occurs (in the United States, church attendance was up after 9/11), which may either bring solace or make things worse (Burke et al., 2013; Thuné-Boyle et al., 2013).

Are there gender differences in preferred coping styles? Men may be problem-

Females, however, may be emotion-

This distinction appeared among 634 mothers and fathers who had lost a baby, either stillborn at birth or dying within the first days and months of life (D. Christiansen et al., 2014). The women were more likely to anxiously seek social support from other people (sometimes overprotecting another child), and men were more likely to avoid attachment (sometimes spending hours away from home).

Gender differences should not be exaggerated. Both problem-

CHOOSING METHODS Not only do adults of both sexes need to find the best strategy for each particular problem, but they also need to decide who will help, how and when (Aldwin, 2009). Getting social support is generally a good strategy—

weathering

The gradual accumulation of stressors over a long period of time, wearing down a person’s resilience and resistance.

Related to social support is the overall social context, which may diminish stress or may increase it. A U.S. study of 65,000 adults compared biomedical signs of poor health, such as hypertension and insulin resistance, which collectively are called weathering. In this study, weathering happened faster among African Americans—

One explanation is that something within African Americans (their genes? their diet? their personal coping style?) causes faster weathering. However, the authors of this study blame the “chronic stress” of living in a “race-

Ideally, with age and experience adults learn to respond wisely, and social supports are in place so that trauma—

Optimization with Compensation

selective optimization with compensation

The theory that people specialize in some abilities and to ameliorate any physical and cognitive losses they may experience.

Paul and Margret Baltes (1990) developed a theory called selective optimization with compensation to describe the “general process of systematic functioning” (P. Baltes, 2003, p. 25). They believe that people seek to optimize their development, selecting the best way to compensate for physical and cognitive losses, becoming more proficient at activities they want to perform well and deciding to avoid other tasks.

Selective optimization with compensation applies to every aspect of life, from choosing friends to playing baseball. Each adult seeks to maximize gains and minimize losses, practicing some abilities and ignoring others. Such choices are critical, because any ability can be enhanced or diminished, depending on how, when, and why a person uses it. It is possible to “teach an old dog new tricks,” but adults need to choose to learn those new tricks.

Research on adult cognition finds that, when adults are motivated, few age-

As Baltes and Baltes (1990) explain, selective optimization means that each adult selects certain aspects of intelligence to optimize and neglects the rest. If the ignored aspects happen to be the ones measured on intelligence tests, then IQ scores will fall, even if the adult’s selection improves (optimizes) other aspects of intellect. The brain is plastic over the life span, developing new dendrites and activation sequences, adjusting to whatever the person chooses to learn (Karmiloff-

For example, suppose someone is highly motivated to learn about a particular area of the world, perhaps East Timor, a tiny independent nation since 2002. That someone goes to the library, selecting key articles and the two dozens books in English about East Timor, ignoring other interesting topics (selection).

Then suppose that aging vision makes it hard to read the fine print of some news articles about East Timor. Time for compensation—new glasses, a magnifier, increased font size. Some bits of knowledge may be pivotal: Note-

If the expert on East Timor takes an IQ test that includes tamarind as a vocabulary word, that person might score high in vocabulary but fail questions of general knowledge. Thus, knowledge increases in depth but decreases in breadth.

Expert Cognition

Another way to describe gains and losses, or selective optimization with compensation, is to say that every adult is an expert in something. Each adult specializes in whatever is personally meaningful, anything from car repair to gourmet cooking, from illness diagnosis to fly fishing. One of my students said she was an expert in makeup; she always looked beautiful.

As people develop expertise in some areas, they pay less attention to others. For example, everyone watches only a few television channels or none at all, ignoring vast realms of experience. Each person has no interest in attending certain events for which others wait in line for hours. I wish my beautiful student had wanted to be an expert in developmental psychology, but adulthood has taught me that my passions are not shared by everyone.

Culture and context guide us in selecting areas of expertise. Many adults born 60 years ago are much better than more recent cohorts at penmanship, which was taught by their teachers in childhood. Those students practiced, became experts, and now maintain expertise.

Today’s adults make other choices for children. Reading, for instance, is currently considered crucial, unlike a century ago when adult illiteracy was common. Parents buy blocks with letters on them for babies and read books to toddlers. Teachers and parents are pleased when kindergartners can read, unlike 50 years ago when reading began in first grade. Schools are closed down if too many third-

Experts, as cognitive scientists define them, are not necessarily people with rare and outstanding proficiency. Nor are they simply people who are competent at a particular skill (Tracey et al., 2014). Although sometimes the term expert connotes an extraordinary genius, to researchers it means more—

Video: Expertise in Adulthood: An Expert Discusses His Work In this video, Kenneth Davis discusses his research on how the neurotransmitter acetylcholine affects memory.

INTUITIVE Novices follow formal procedures and rules. Experts rely more on past experiences and immediate contexts; their actions are therefore more intuitive and less stereotypic than those of the novice. The role of experience and intuition is evident in every vocation, from surgeons to musicians, from teachers to truck drivers.

One study compared psychotherapists, both experienced and new—

This conclusion needs to be qualified, however. A review of expertise and therapy found that, although they generally improve the lives of their clients, few therapists become genuine experts. Needed is more feedback and readjustment based on the eventual outcomes of their clients—

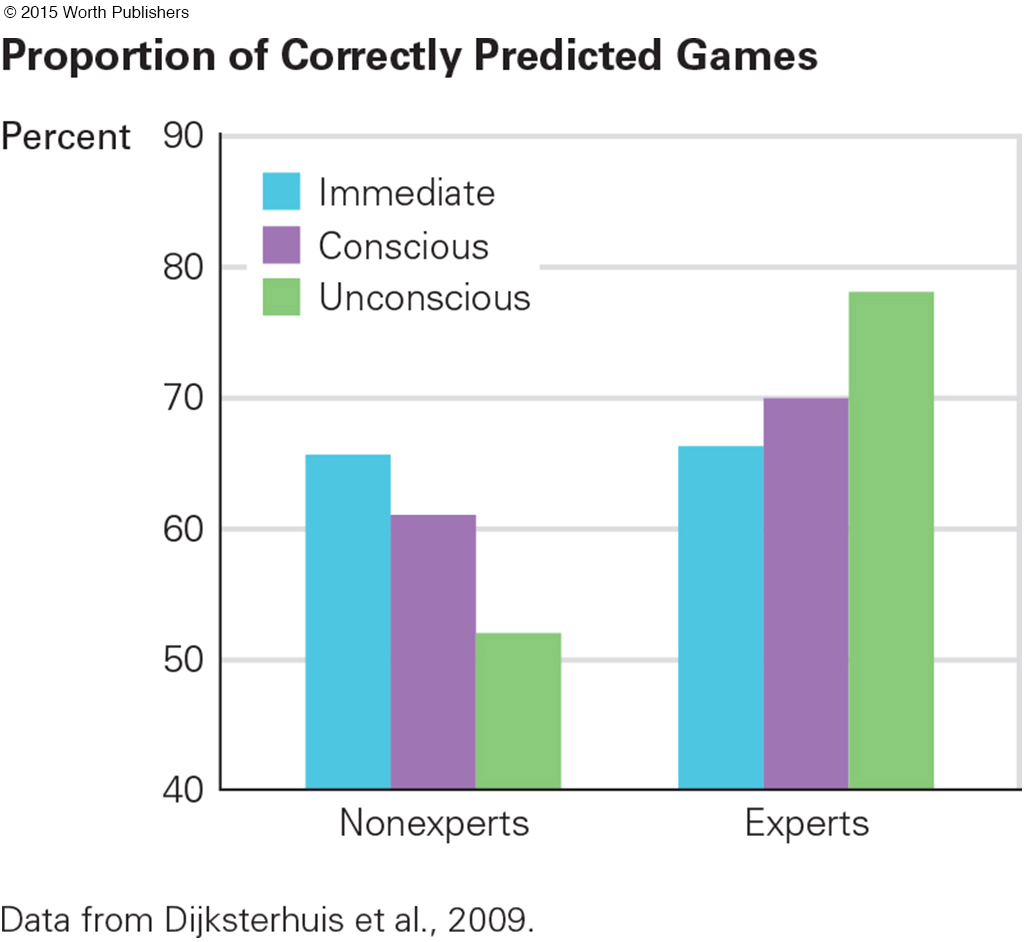

An experiment involved 486 Dutch college students, asked to predict the winners of four World Cup soccer matches soon to be played. The students who were avid fans (the experts) made better predictions when they had two minutes of unconscious thought (when they could not think about soccer because they had to solve a difficult math problem) than when they had time to mull over their choice (see Figure 12.7).

Those who didn’t care much about soccer (the nonexperts) did poorly overall, but they did worse when they had time to use unconscious intuition (Dijksterhuis et al., 2009). Intuition works for experts, but not for others.

AUTOMATIC This experiment with soccer experts and nonexperts also confirms that many elements of expert performance are automatic; that is, the complex, time-

This is apparent if you have tried to teach someone to drive. Excellent drivers who are inexperienced instructors do not recognize or verbalize automatic knowledge—

This may explain why, despite powerful motivation, quicker reactions, accurate knowledge of road rules, and better vision, teenagers’ rate of fatal car accidents is three times that of adults (Insurance Institute, 2012). Sometimes they take risks (speeding, running a red light, drinking, and so on), but often they simply misjudge and misperceive conditions that a more experienced driver would automatically notice.

The same gap between knowledge and instruction occurs when a computer expert tries to teach a novice what to do, as I know myself when my daughters try to help me with the finer points of Excel. They are unable to verbalize what they know, although they can do it very well on my computer. It is much easier to click the mouse or do the keystroke oneself than to teach someone else what has become automatic.

The fact that such skill is automatic, not the result of increased motivation or practice, was evident in EEGs of the brain activity in musicians and non-

automatic processing

Thinking that occurs without deliberate, conscious thought. Experts process most tasks automatically, saving conscious thought for unfamiliar challenges.

Automatic processing is thought to explain why expert chess and Go players are much better than novices. They see a configuration of game pieces and automatically encode it as a whole, rather than analyzing it bit by bit. A study of expert chess players (aged 17 to 81) found minor age-

This was particularly apparent for speedy recognition that the king was threatened: Older experts did that in a fraction of a second, almost as quickly as younger adults who knew the game well, despite the elders’ steep, age-

When something—

STRATEGIC Experts have more and better strategies, especially when problems are unexpected. Indeed, strategy may be the most pivotal difference between a skilled and an unskilled person, as the skilled person has sufficient experience to be able to have alternate strategies available when new problems arise.

Determining how people choose strategies is a complex question (Marewski & Schooler, 2011), and it is difficult to compare experts and novices except to note that experience prevents panic. Expert chess players have general strategies for winning and dozens of specific strategies that prevent quitting too readily, or continuing to play when checkmate is inevitable (Bilalić et al., 2009).

Scientists seek to understand the variations and origins of cognitive strategies needed to sort through the many bits of information that are accumulated over the years. Experts use their cognitive reserve (a special form of organ reserve) to develop appropriate strategies (Barulli & Stern, 2013).

Expertise has been demonstrated in the following areas: “computer programing, chess playing, teaching . . . playing bridge, solving algebra word problems, solving economic problems, and judicial decision making” (Tracey et al., 2014, p. 220). Considering those, you can see that effective strategies are essential—

Another example, familiar to everyone, is teaching. Think about your most expert professor. He or she institutes routines and policies early in the semester, which are strategies for avoiding problems later. If a sudden student outburst occurs, the expert calms the student and uses that to teach; the novice professor might be unnerved and make things worse.

Question 12.37

OBSERVATION QUIZ

What two sets of skills are needed for this nurse?

Medical expertise and interpersonal skills. Puncturing the finger to draw blood must be automatic, but her response to the patient must be intuitive and flexible—

FLEXIBLE Finally, perhaps because they are intuitive, automatic, and strategic, experts are also flexible. The expert artist, musician, or scientist is creative and curious, deliberately experimenting and enjoying the challenge when unexpected things occur (Csikszentmihalyi, 2013). Remember Pavlov (Chapter 1). He already had won the Nobel Prize when he noticed his dogs’ unexpected reaction to being fed. His expertise made him notice, then investigate, and eventually develop insights that opened a new perspective in psychology.

Experts in all walks of life adapt to individual cases and exceptions—

In the field of education, best practices for the educator emphasize flexibility and strategy, as each group of students has distinct and often erroneous assumptions. It is not helpful to simply teach the right answers; flexibility requires matching the instruction to the individual students, discovering what learning is needed (Ford & Yore, 2012).

A review of expertise finds that flexibility includes understanding which particular skills are necessary to become an expert in each profession. For example, repeated practice is needed in typing, sports, and games; collaboration skills are needed for leadership; and task management strategies are needed for aviation (Morrow et al., 2009). Practice is not merely rote repetition; it must be deliberate, allowing learning from experience (Ericsson, 2006).

EXPERTISE AND AGE The relationship between age and expertise is not straightforward. Much depends on the task: The young have an advantage when speed is needed, but they are less adept at vocabulary. Further, they have less experience, which may be crucial for some tasks, and they have had less time to practice—

An interesting example of age and practice comes from perfumers. For that profession, an acute sense of smell is essential as they seek to develop new scents. Usually the sense of smell is reduced with age, but this does not seem true for perfumers. One study found that older experts outdid younger nonexperts at detecting smells, because parts of the professionals’ brains were better developed for smell (Delon-

This illustrates a general conclusion from research on cognitive plasticity: Experienced adults often use selective optimization with compensation, becoming expert. This is apparent in many workplaces. The best employees may be the older, more experienced ones—

Complicated work requires more cognitive practice and expertise than routine work; as a result, such work may have intellectual benefits for the workers themselves. In the Seattle Longitudinal Study, the cognitive demands of the occupations of more than 500 workers were measured, including the complexities involved in the interactions with other people, with things, and with data. In all three occupational challenges, older workers maintained their intellectual prowess (Schaie, 2005/2013).

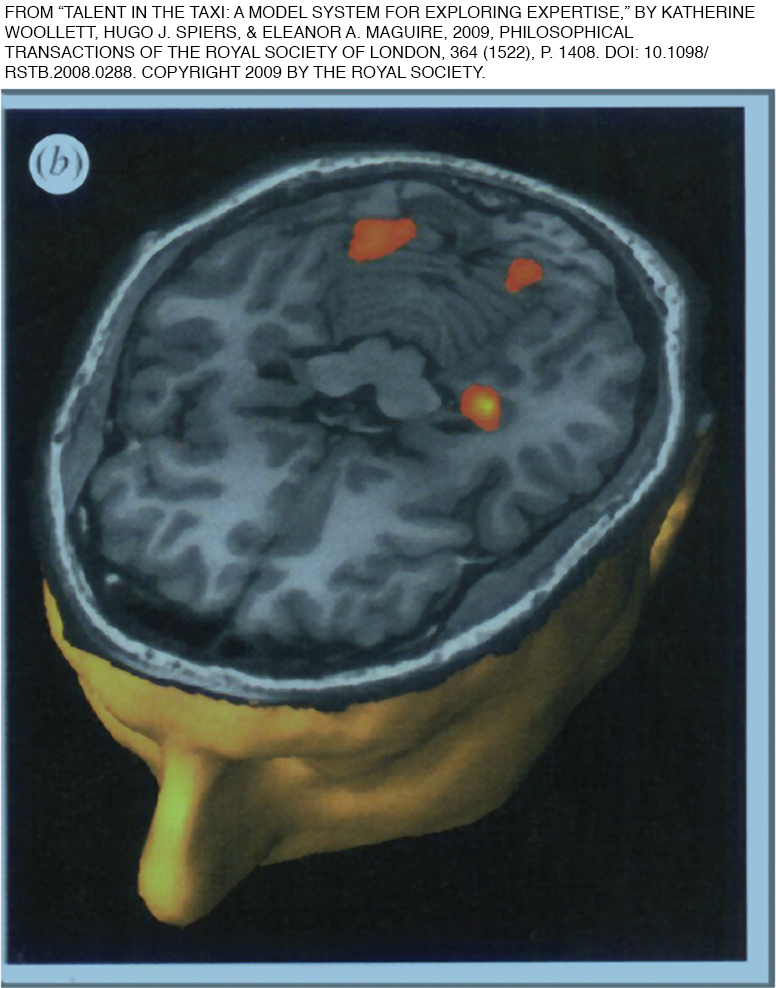

One final example of the relationship between age and job effectiveness comes from an occupation familiar to all of us: driving a taxi. In major cities, taxi drivers must find the best route (factoring in traffic, construction, time of day, and many other details). They also must know where and when new passengers are likely to be and who wants to talk, who wants silence, and how to respond when the passenger has opinions the driver finds narrow and wrong. Expert drivers earn far more in tips than novices; they have learned from experience.

Research in England—

Other studies also show that people become more expert, and their brains adapt, as they practice various skills (Park & Reuter-

Now we return to Jenny, who left my office decades ago. As I wrote, she came to me because I am an expert in human development, but over the years I have realized that her expertise regarding her life contexts was far ahead of mine.

A CASE TO STUDY

Jenny, Again

A dispassionate analysis of Jenny’s situation when she consulted me would conclude that another baby—

But those statistics do not reflect Jenny’s intelligence, creativity, and practical expertise. She already had a habit of gathering social support, evident by her seeking me out. She was not daunted by her poverty; remember, she found many free activities for her children to enjoy, including sending them on vacation in the country. She was exceptional, but not unique: Some low-

Jenny used her knowledge well. She asked Billy to be tested for sickle-

When she was 8 months pregnant, she interviewed for a city job tutoring children in her home. She hoped to earn money while caring for her newborn (a full-

I brought baby clothes to her railroad apartment on the eighth floor of the projects. I noticed that her framed Bronx Community College diploma was not displayed. She explained that she feared that the city investigator, who would come to her house to see whether it was adequate for tutoring, might decide she was overqualified. That was expertise: She got the job.

When her baby was a little older, Jenny headed back to college, earning a BA on a full scholarship. Her peers and professors recognized her intelligence: She gave the student speech at graduation. The two orphaned nephews reached age 18 and moved out.

She then found work as a receptionist in a city hospital, a job that provided day care and health benefits for her and her three children. That allowed her to move to a better neighborhood of the Bronx (Co-

Billy continued to visit Jenny and the daughter he had not wanted. His wife became suspicious and hired a detective to follow him—

At that point, I realized that Jenny had some insight into human relations that I did not recognize in my office years earlier: Billy chose divorce and married Jenny. Within a few years, they moved to Florida, where Jenny earned a master’s degree (she phoned to say she was assigned my textbook) and then worked as a supervisor in a public school. Their young daughter graduated from high school in Florida.

The last time I saw her, I learned that she bikes, swims, and gardens every day. I met her speech-

Not everyone becomes an expert in human relations; Jenny is exceptional in many ways. But one lesson from this chapter is that health, intelligence, and even wisdom may improve over the years of adulthood. As further explained in Chapter 13, choices and relationships affect how lives unfold, true for Jenny and for us all.