Prejudice and Predictions

ageism

A prejudice whereby people are categorized and judged by their chronological age.

Ageism is the idea that age determines whom a person is, and therefore everyone should “act their age.” Age restricts what we do, usually to our detriment. That makes ageism “a social disease, much like racism and sexism” causing “needless fear, waste, illness, and misery” (Palmore, 2005, p. 90).

Believing the Stereotype

Ageism becomes a self-

If people of any age treat older people as if they are frail and confused, that treatment might make them become more dependent on others.

If people believe that the norms for young adults should apply to everyone, they may try to fix the old. If they fail, they give up.

Many older people themselves are ageist. For example, most people older than 70 say they are doing better than other people their age—

If the elderly attribute their problems to their age, they may not try to change themselves or the situation. For example, if they forget something, they laugh it off as a “senior moment,” not realizing the ageism of that reaction. The research confirms that many of the elderly are ageist—

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

I’m Not Like Those Other Old People

My mother, in her 80s, was reluctant to enter an assisted-

Asked how old they feel, most 80-

This same phenomenon is apparent for every aspect of functioning in late adulthood. One study asked people to estimate trajectories over the life span of six cognitive functions and four social ones (Riediger et al., 2014). People of all age groups estimated declines, usually by age 60 and clearly by age 80. That is accurate: Many declines occur.

However, on every measure, older people were most likely to estimate that their own functioning was better than the average older person (see table). This was particularly true for memory, speed, and making new friends—

| 9- |

13- |

21- |

70- |

|

| Memory | Better | Same | Worse | Better |

| Cognitive speed | Same | Worse | Worse | Better |

| Mental math | Better | Same | Worse | Better |

| Concentration | Same | Same | Worse | Better |

| New friends | Same | Worse | Worse | Better |

| Self- |

Better | Same | Same | Better |

Adapted from Riediger et al., 2014.

THINK CRITICALLY: How do you compare to other people your age?

In an ageist culture, feeling younger and better than others of your chronological age is understandable. As one commentator noted, “feeling youthful is more strongly predictive of health than any other factors including commonly noted ones like chronological age, gender, marital status and socioeconomic status” (Barrett, 2012, p. 3).

Indeed, how a person thinks of old age affects recovery from major illness (Levy et al., 2012). One study began with 598 healthy people age 70 or older. They were asked, “When you think of old persons, what are the first five words or phrases that come to mind?” Answers ranged from very negative (e.g., decrepit, demented) to very positive (e.g., wise, active).

Over the next decade, many of those 598 experienced disabilities. Some temporarily could not walk, feed themselves, go to the toilet, or even get out of bed. Many had surgery or were hospitalized, requiring intensive care. Then most got better. How quickly and completely they recovered from each episode was affected by many expected factors, such as SES, other illnesses, and age.

However, when those known factors were taken into account, recovery was strongly affected by earlier attitudes. Among those who experienced serious disabilities, the ones who had listed positive words about aging became completely independent again 44 percent more often than those who had been very negative (Levy et al., 2012).

Stereotype threat—

Of course, health conditions and slower movement are not simply the result of ageism. Without the distortions of ageism, changes need to be understood for what they are, with adjustment and accommodation, not with despair or desperation.

Elders must find “a delicate balance . . . knowing when to persist and when to switch gears . . . some aspects of aging are out of one’s control” (Lachman et al., 2011, p. 186). Recognition of the reality of age, without ageism, is needed.

What’s the Harm?

One expert contends that

there is no other group like the elderly about which we feel free to openly express stereotypes and even subtle hostility. . . . most of us . . . believe that we aren’t really expressing negative stereotypes or prejudice, but merely expressing true statements about older people when we utter our stereotypes . . .

[Nelson, 2011, p. 40]

Many people think they are protective and kind toward older people. Is there any harm in that? Yes. Let us now consider elderspeak, hearing aids, sleep, and exercise.

elderspeak

A condescending way of speaking to older adults that resembles baby talk, with simple and short sentences, exaggerated emphasis, repetition, and a slower rate and a higher pitch than used in normal speech.

AGEIST TALK Utterances that seem benign (“so cute,” “second childhood,” “all her marbles”) are part of a general infantilizing of the elderly, treating them as if they were children (Albert & Freedman, 2010). Ostensible kindness is actually harmful. A specific example is elderspeak—the way people talk to the old (Nelson, 2011).

Like baby talk, elderspeak uses simple and short sentences, slower talk, higher pitch, louder volume, and frequent repetition. Elderspeak is especially patronizing when people call an older person “honey” or “dear,” or use a nickname instead of a surname (“Billy,” not “Mr. White”).

Health professionals are particularly likely to use elderspeak and consider it appropriate (Lombardi et al., 2014). They tend to judge everyone based on their experience with elders who are sick and failing and who may need louder voices and simpler explanations. If that becomes their stereotype, then their prejudice is hard to remove (Williams et al., 2009).

Ironically, elderspeak reduces communication. Higher frequencies are harder for the elderly to hear, stretching out words makes comprehension worse, shouting causes anxiety, and simplified vocabulary reduces precise communication.

If older people often are addressed with simple, loud speech, they begin to believe that everyone is annoyed at them. Worse, since the mind is stimulated by new ideas that are explained, disputed, and elaborated with nuanced vocabulary and complex sentences, elderspeak reduces cognition.

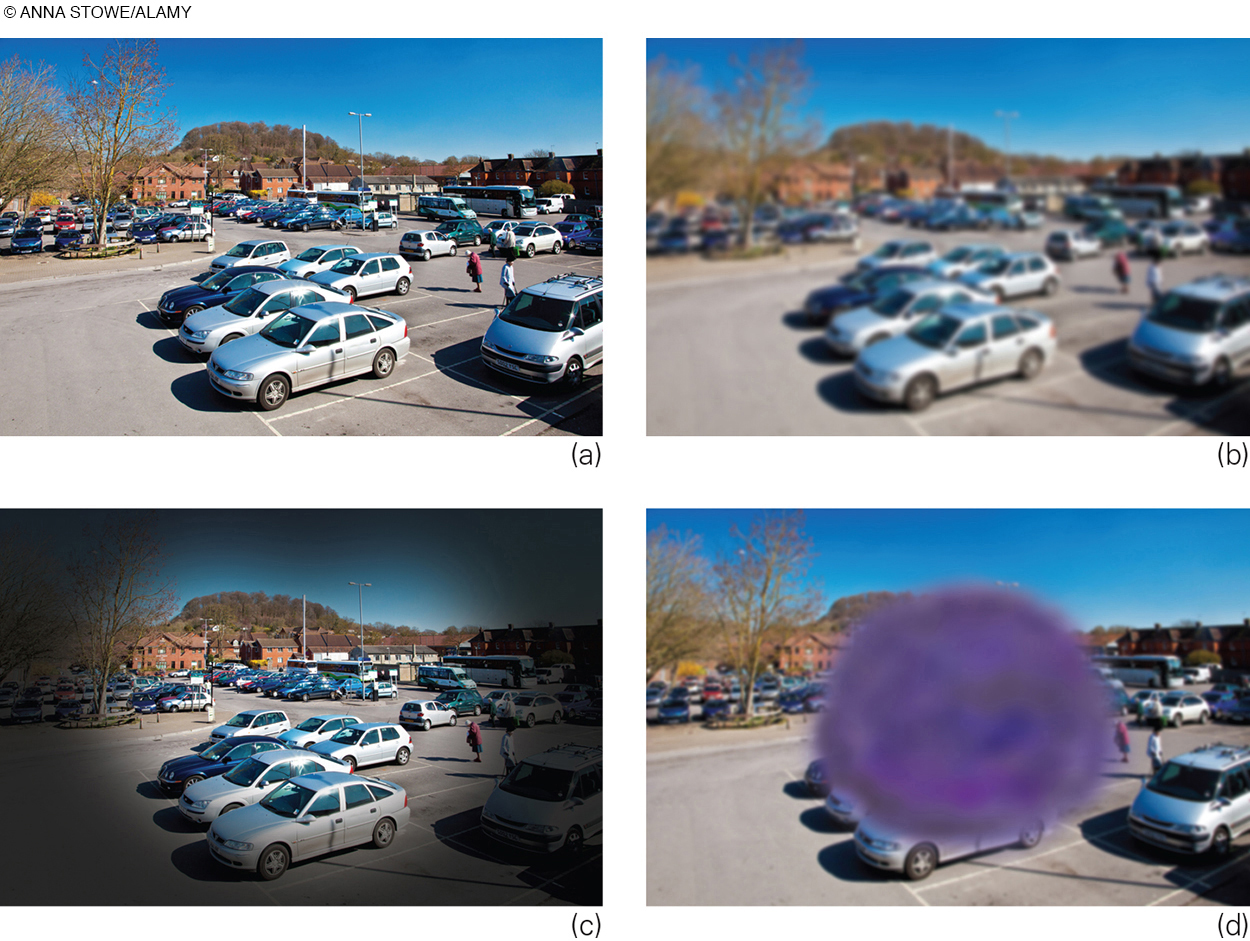

SENSORY LOSS AND AGEISM Another cognitive loss occurs when sensory loss leads to isolation, immobility, and reduced intellectual stimulation. It is true that all the senses fade with age. This is true for touch (particularly in fingers and toes), taste (particularly for sour and bitter), and smell (is that burning?), as well as for the two senses that are most crucial, sight and hearing.

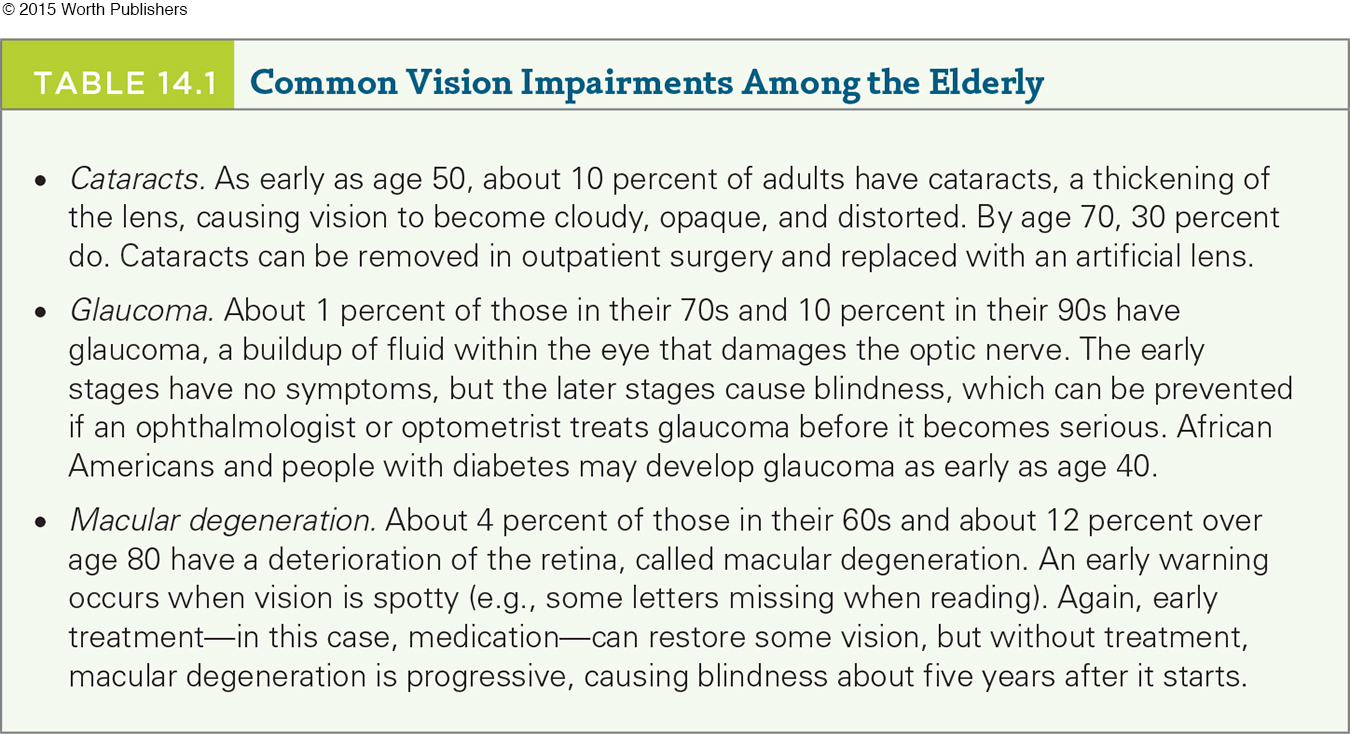

Only 10 percent of people over age 65 see well without glasses. Many suffer from specific vision problems (see Table 14.1). A minority (about 12 percent) report vision problems even with corrective lenses (National Center for Health Statistics, 2014).

Hearing is most acute at about age 15 and fades slowly from then on, with men twice as likely to lose hearing as women. The Gallaudet Research Institute says that 29 percent of those over age 65 have serious hearing problems; a scholar who examined U.S. Census records suggests about half that, 16 percent (Mitchell, 2006).

Sensory loss is real, but ageism makes it worse. Not only do people yell at older people who can hear well, but if elders need hearing aids they may refuse them for fear they will appear old. Consequently, their own ageism makes them miss half of what people say. Because of that, other people may exclude them, which increases isolation, decline, and depression.

universal design

The creation of settings and equipment that can be used by everyone, whether or not they are able-

Thus, sensory loss may lead to cognitive decline. Disability advocates seek universal design, which is the creation of settings and equipment that can be used by everyone, whether able-

SLEEP AND EXERCISE How exactly does ageism harm health? Again and again the research concludes that physical exercise and adequate sleep are the foundation for wellness. Both are undercut by ageism.

Consider sleep. The day–

However, ageism leads everyone to expect the old to sleep like the young. That expectation leads to distress. That may be why frequent night waking correlates with depression, why doctors prescribe narcotics, or why people drink alcohol to put themselves to sleep. Drugs seem to be a quick fix, but they often overwhelm an aging body, causing heavy sleep, confusion, nausea, and unsteadiness.

What can be done if ageism does not interfere? In one study, older adults complaining of sleep problems were mailed six booklets (one each week) (K. Morgan et al., 2012). The booklets described normal patterns for people their age and gave suggestions to relieve insomnia.

Compared to a control group of older people with sleep complaints who did not get the booklets, six weeks later the informed elders used less sleep medication and reported better sleep. Those benefits were still apparent six months after the last booklet. No nightcaps needed.

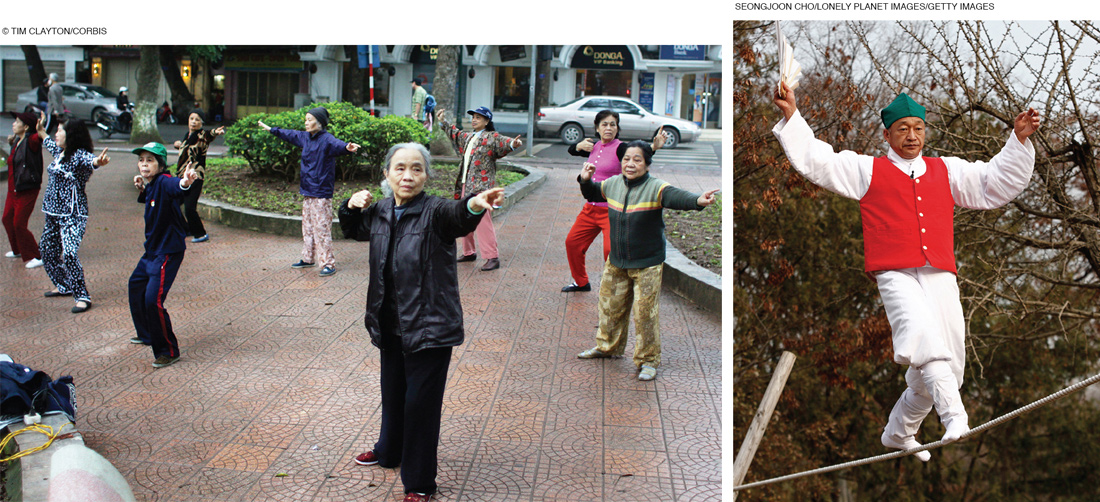

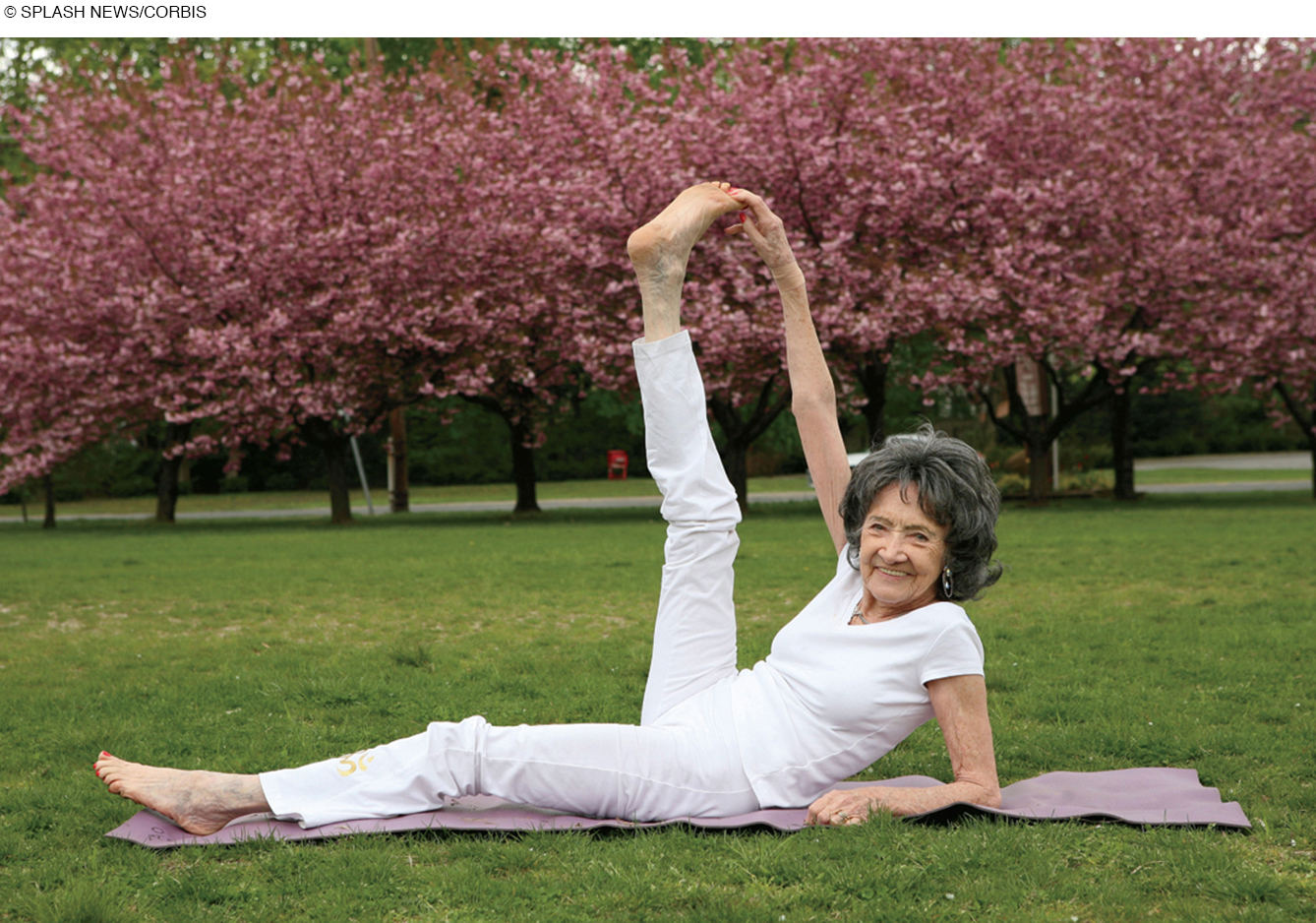

A similar phenomenon is apparent with regard to exercise. Sports leagues, exercise classes, and athletic shoes are designed for young bodies. Picture the reaction if an old man tries to join a neighborhood pick-

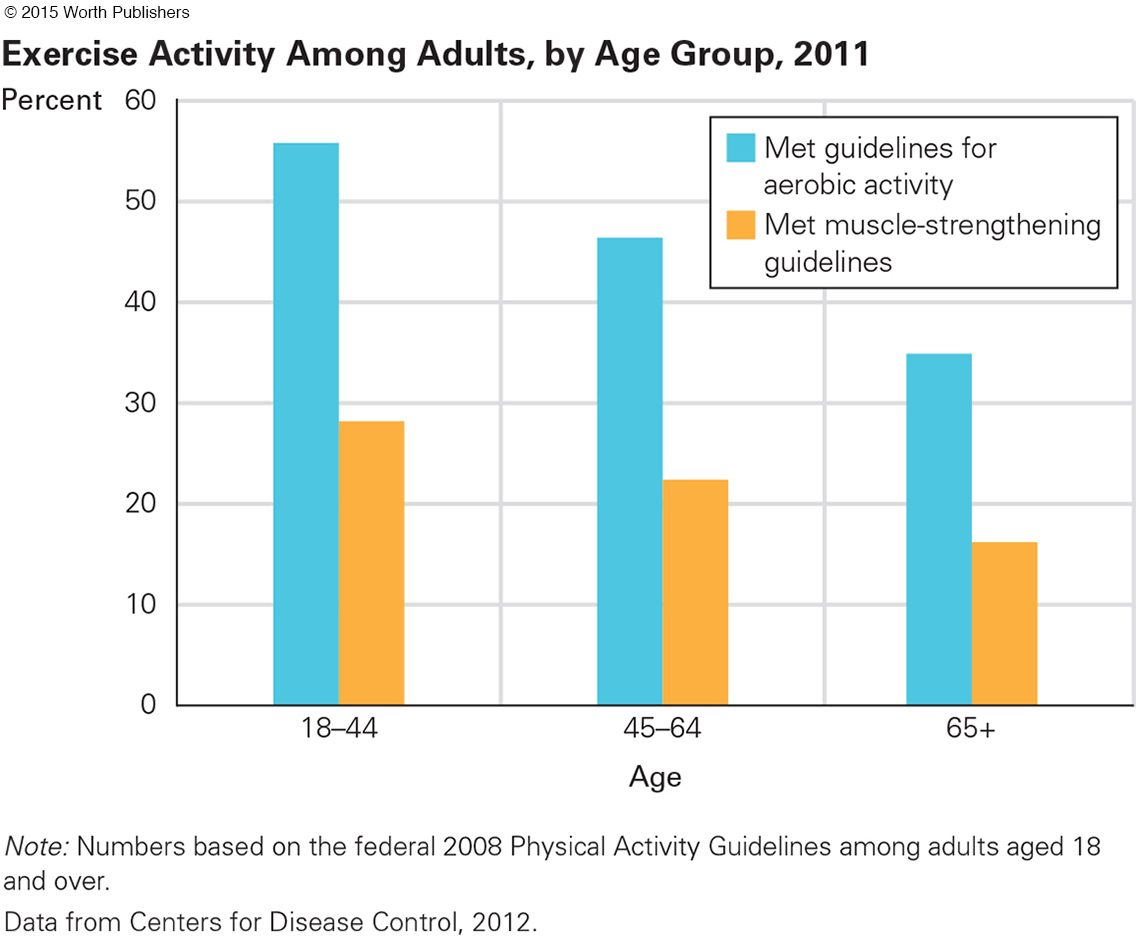

As a result, the elderly conclude that exercise is not for them. In the United States, of those over age 65, only 35 percent meet the recommended guidelines for aerobic exercise, compared with 56 percent for adults aged 18 to 44 (National Center for Health Statistics, 2013) (see Figure 14.1). Meeting the guidelines for muscle strengthening was worse; only 16 percent of the aged did so. Blame ageism.

Advertisements induce younger adults to buy medic-

Instead, younger adults could go hiking or biking with their older relatives. Lest you think that bikes are only for children, a study of five nations (Germany, Italy, Finland, Hungary, and the Netherlands) found that 15 percent of Europeans older than 75 ride their bicycles every day (Tacken & van Lamoen, 2005).

Other accommodations—

The Demographic Shift

demographic shift

A shift in the proportions of the populations of various ages.

Demography is the science that describes populations, including population by cohort, age, gender, or region. Demographers describe “the greatest demographic upheaval in human history” (Bloom, 2011, p. 562), a demographic shift in the proportions of the population of various ages.

In earlier centuries, there were 20 times more children than older people, and a mere 50 years ago the world had 7 times more people under age 15 than over age 64. In 2015, U.N. estimates are 3-

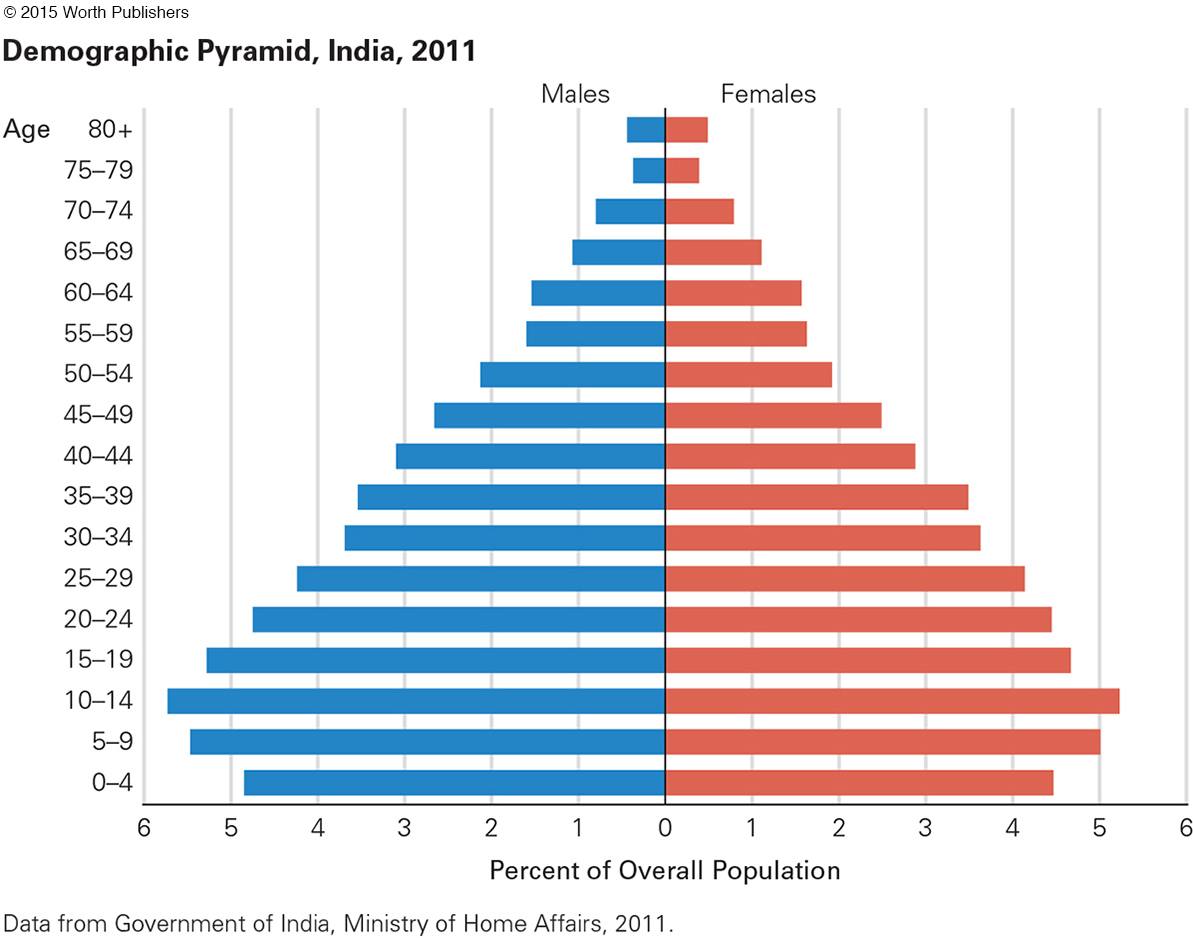

Visual evidence for this comes from what has been called the demographic pyramid. For centuries, each younger group has been larger than the next older one, for two reasons: (1) Most families had many children, and (2) deaths occurred at every age. The demographic pyramid is still evident in some developing nations (see Figure 14.2).

Question 14.1

OBSERVATION QUIZ

Does India have more males or more females?

More males, except for the very old. Why is that?

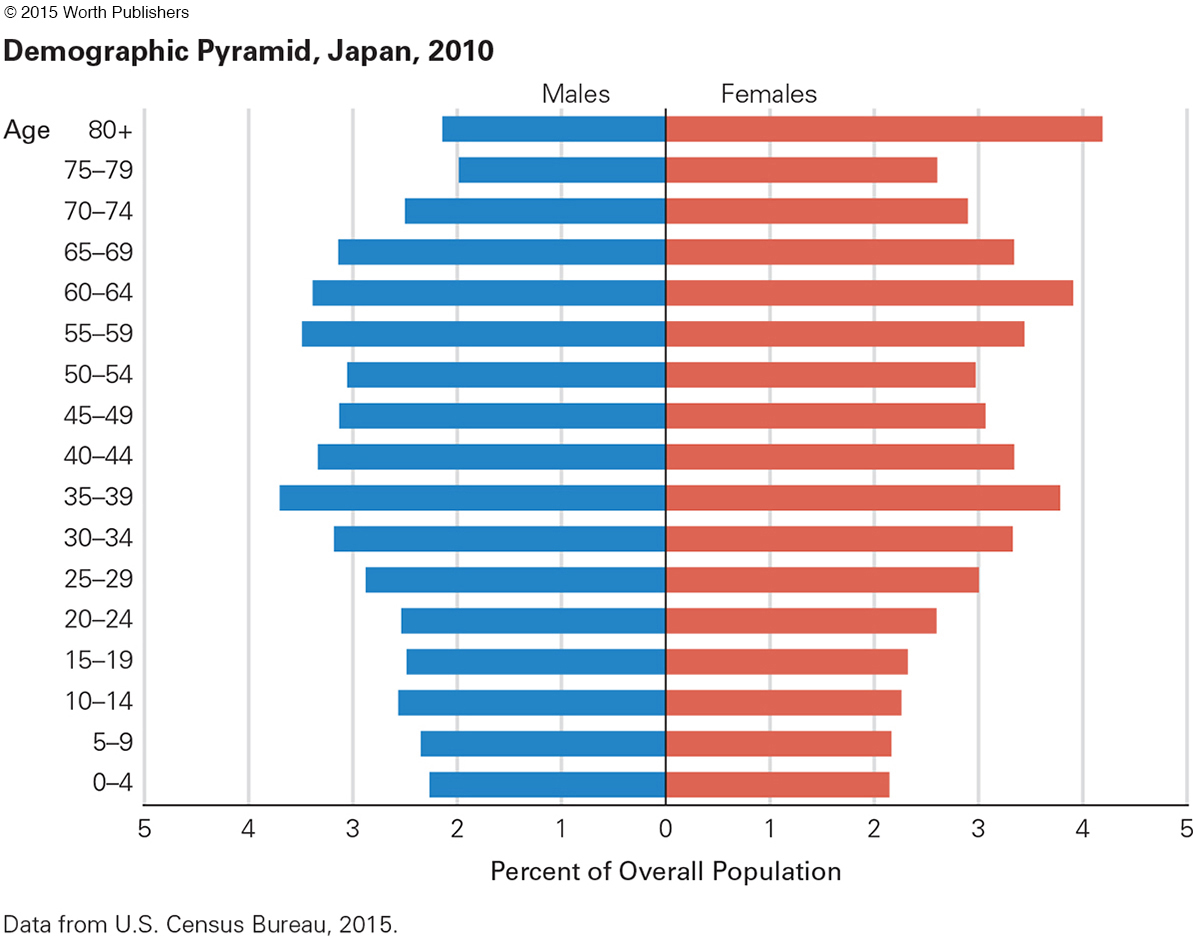

If every nation produced an average of 2.1 children per family, and if few people died before old age, the demographic shape would look more like a square than a pyramid. That is true now in several nations (see Figure 14.3).

Indeed, if most families continue to have fewer than two children (true in about 80 nations now), if almost everyone survives until old age (increasingly true in developed nations), and if restrictions in many nations limit immigration, then the pyramid will be upside down, as is projected for Japan.

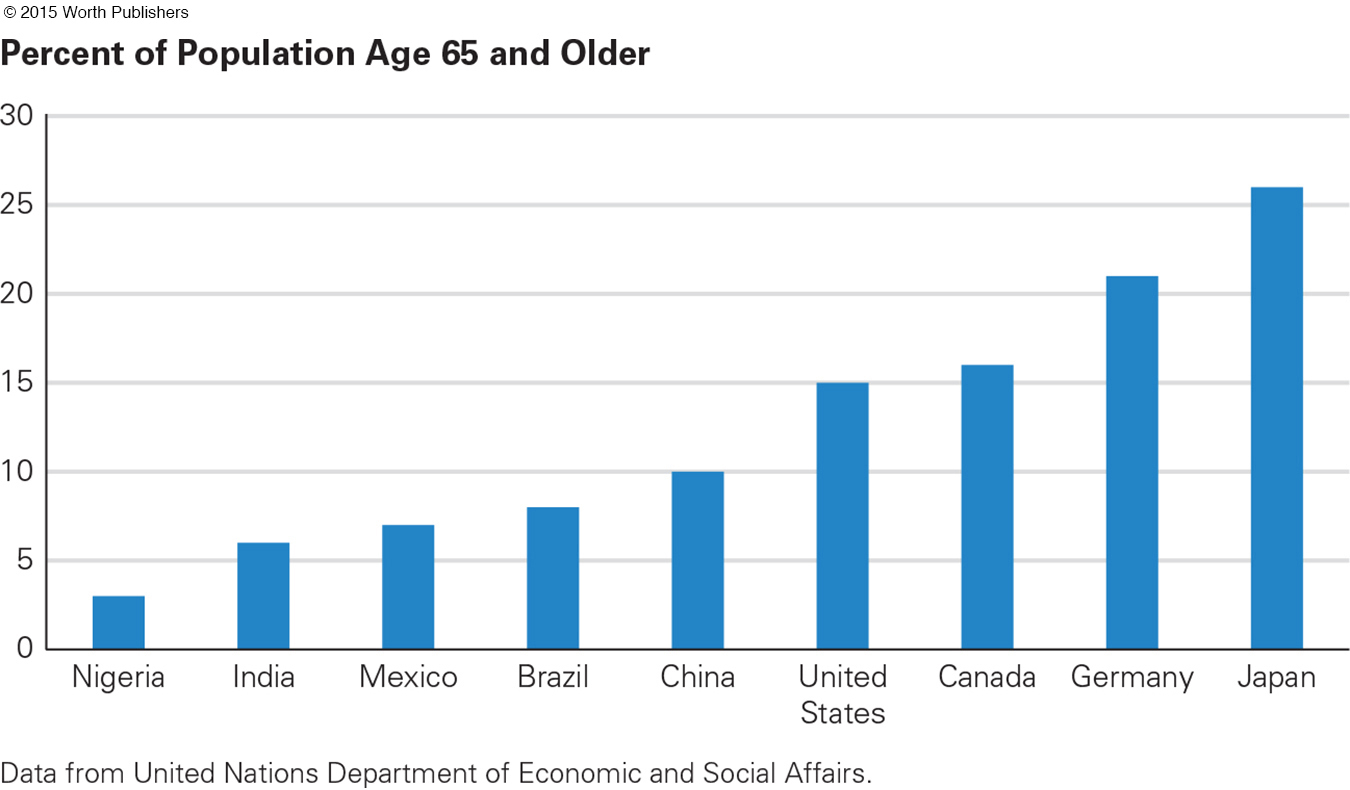

In 2015 an estimated 8 percent of the world’s population is 65 or older, compared with only 2 percent a century earlier. This number is expected to double by the year 2050. Proportions of the population over age 65 vary markedly by nation (see Figure 14.4.)

Worldwide, children (under age 15) outnumber elders (65+) more than 3-

Unfortunately, demographic data are sometimes reported in ways designed to alarm, and ageism makes people ready to believe the worst. For instance, have you heard that people aged 80 and older are the fastest-

Stating the facts that way triggers ageist fears of hungry hordes of frail and confused elders. Pensions will bankrupt nations. The haunting specter is of crowded hospitals and nursing homes, costing taxpayers billions of dollars.

But consider the facts. We use the United States as an example. In 2015 there were more than four times as many people over age 80 than 50 years earlier (12.0 million compared with 2.7 million). But the population has also grown. The percentage of the population aged 80 and older has doubled, not quadrupled (from 1.6 percent to 3.7 percent, 1965–

Theories of Aging

Underlying our study of aging is a fundamental question: Why do people age? If we could stop senescence, or even slow down the aging process, we could decrease the rate of cancer, heart diseases, strokes, and every frailty that undermines the body and brain.

Video: Portrait of Aging: Mary

Hundreds of theories and thousands of scientists have tried to understand the biology of aging, with the hope that understanding will lead to ways to slow the process. To simplify, these theories are grouped in three clusters: wear and tear, genetic adaptation, and cellular aging.

wear and tear

A view of aging as a process by which the human body wears out because of the passage of time and exposure to environmental stressors.

STOP MOVING? STOP EATING? The oldest, most general theory of aging is known as wear and tear. The idea is that the body wears out, part by part, after years of use. Organ reserve and repair processes are exhausted as the decades pass (Gavrilov & Gavrilova, 2006).

This theory begins by recognizing that some body parts suffer from overuse. Athletes who put repeated stress on their shoulders or knees may have chronically painful joints by middle age; workers who inhale asbestos and smoke cigarettes damage their lungs; hockey, football, and boxing stars who suffer repeated blows to the head may destroy their brains.

In addition, sometimes the body wears out because of weather, or harmful food, or pollution, or radiation. For instance, skin cancer is caused partly by too much sun, clogged arteries are caused partly by too much animal fat, and some cancer tumors result from too much pollution and radiation.

Every older person’s hands and face are wrinkled, often with discolorations known as “age spots.” By contrast, the skin on the torso may be smooth and clear, even at age 80. The reason is wear and tear via daily sun, wind, and cold to the face, but almost never to the stomach.

However, most scientists have rejected wear and tear as a general theory of aging, because other body functions benefit from activity. Exercise improves heart and lung functioning; tai chi improves balance; weight training increases muscle mass; sexual activity stimulates the sexual-

calorie restriction

The practice of limiting dietary energy intake (while consuming sufficient quantities of vitamins, minerals, and other important nutrients) in hopes of slowing down the aging process.

An astonishing finding from lower animals suggests an application of wear and tear. If an adult reduced wear and tear on digestion, metabolism, and so on by eating 1,800 calories a day instead of the usual 3,000, would that slow all aging processes? Calorie restriction—a drastic reduction in calories consumed—

The most dramatic evidence comes from fruit flies, which can live three times as long if they eat less. Many other species benefit from calorie restriction, but not all. Some research on monkeys, mice, and other animals reports that calorie restriction extends life, but other research does not (Mattison et al., 2012).

Results may depend on small genetic differences between one species (or strain of mice) and another, or on details of the diet. Some research suggests that a high-

Regarding humans, thousands of members of the Calorie Restriction Society voluntarily undereat (Roth & Polotsky, 2012). They give up some things that many people cherish, not just cake and hot dogs but also a strong sex drive and high energy. As a result, they have lower blood pressure, fewer strokes, less cancer, and almost no diabetes. But that does not convince most scientists, in part because they are a self-

THINK CRITICALLY: Do people want the comforts of daily life—

In several places (e.g., Okinawa, Denmark, and Norway), wartime occupation forced severe calorie reduction for almost everyone. People ate local vegetables, and not much else, and they were often hungry. But they were less likely to die of disease (Fontana et al., 2011).

Similar results were reported from Cuba, already mentioned in Chapter 12. Because the United States led an embargo of Cuban products, that nation experienced food and gas shortages from 1991 to 1995. People ate local fruits and vegetables, walked more, and lost weight. Death, particularly due to heart disease and diabetes, was reduced (Franco et al., 2013).

In all these examples, populations benefited when everyone ate less, particularly less meat; but in all these nations, once more food was available, people eagerly ate more. Disease deaths rose again. Apparently, most humans choose some wear and tear in order to live the life they want.

IT’S ALL GENETIC A second cluster of theories focuses on genes, both genes of the entire species and genes that vary from one person to another (Sutphin & Kaeberlein, 2011). About one-

maximum life span

The oldest possible age that members of a species can live under ideal circumstances. For humans, that age seems to be 122 years.

Every species has a maximum life span, defined as the oldest possible age that members of that species can attain (Wolf, 2010). Genes determine the maximum: for rats, 4 years; rabbits, 13; tigers, 26; house cats, 30; brown bats, 34; brown bears, 37; chimpanzees, 55; Indian elephants, 70; finback whales, 80; humans, 122; lake sturgeon, 150; giant tortoises, 180.

average life expectancy

The number of years the average person in a particular population group is likely to live.

Maximum life span is quite different from average life expectancy, which is the average life span of individuals in a particular group. In human groups, average life expectancy varies a great deal, depending on historical, cultural, and socioeconomic factors (Sierra et al., 2009).

The average human life expectancy has more than doubled in the past century and continues to rise. Worldwide, in 2015, the average is about 71 (69 for men, 73 for women). In the United States, in 2015, average life expectancy at birth is 80 (77 for men, 82 for women), eight years more than half a century ago, and projected to be six years longer by 2065 (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2015).

Average life expectancy is increasing primarily because public health measures (clean water, immunization, nutrition, newborn care) prevented many infant and child deaths, and recent medical measures have decreased midlife death from heart disease and cancer.

genetic clock

A mechanism in the DNA of cells that regulates the aging process by triggering hormonal changes and cellular death and repair.

Eventually, however, a genetic clock regulates life, growth, and aging. Just as genes trigger puberty at a certain age, genes may switch on to cause gray hair, slower movement, and, eventually, death. That is true for each species.

In addition, some genes cause unusually fast or slow aging. Children born with Hutchinson-

Other genes seem to program a long and healthy life. People who reach age 100 usually have alleles that other people do not (Govindaraju et al., 2015).

Two alleles of the ApoE gene prove the point. ApoE2 is found in 12 percent of men in their 70s and 17 percent of men over age 85. Those numbers make it apparent that ApoE2 aids survival. However, another allele of the same gene, ApoE4, increases the rate of death by heart disease, stroke, neurocognitive disorders, and—

THINK CRITICALLY: For the benefit of the species as a whole, why would genes promote aging?

Almost every disease is partly genetic, so disease rates vary among people with ancestors from particular parts of the world. For instance, many genes for type 2 diabetes are shared across ethnic groups, but some are more common among African Americans than other U.S. groups (Palmer et al., 2012). For genetic reasons, people with Asian ancestors develop diabetes at younger ages and lower weights than Europeans (Chan et al., 2009; Hsu et al., 2015).

cellular aging

The ways in which molecules and cells are affected by age. Many theories aim to explain how and why aging causes cells to deteriorate.

CELLS QUIT REPRODUCING The third cluster of theories examines cellular aging, focusing on molecules and cells. Remember, cells duplicate many times over the life span, duplicating and reproducing. Minor errors in copying accumulate. Early in life, the immune system repairs such errors, but eventually, the immune system itself becomes less adept.

When the organism can no longer repair every cellular error, senescence occurs. This process is first apparent in the skin, an organ that replaces itself often, particularly if damage occurs (such as peeling skin with sunburn). Cellular aging also occurs inside the body, notably in cancer, as the aging immune system is increasingly unable to control abnormal cells.

Hayflick limit

The number of times a human cell is capable of dividing. The limit for most human cells is approximately 50 divisions, an indication that the life span is limited by our genetic program.

Even without specific infections or stresses, healthy cells stop replicating at a certain point. This point is referred to as the Hayflick limit, named after the scientist who discovered it. Hayflick believes that aging is caused primarily by a natural loss of molecular fidelity—

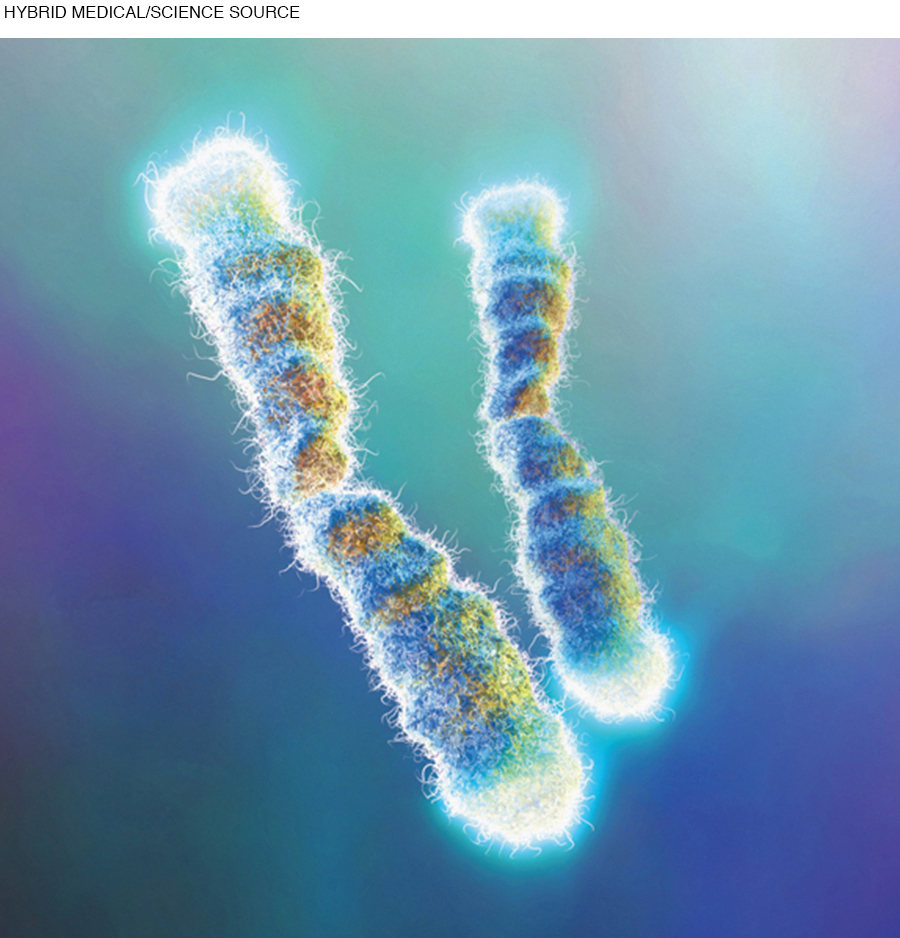

telomeres

The area of the tips of each chromosome that is reduced a tiny amount as time passes. By the end of life, the telomeres are very short.

One cellular change occurs with telomeres—material at the ends of the chromosome that becomes shorter with each duplication. Telomeres are longer in children (except those with progeria) and shorter in older adults. Eventually, at the Hayflick limit, the telomere is gone, duplication stops, and the creature dies (Aviv, 2011).

The length of telomeres is related to both genes and stress. The more stress a person experiences, from childhood on, the shorter their telomeres are in late adulthood and the sooner they will die (J. Lin et al., 2012).

Telomere length is about the same in newborns of both sexes and all ethnic groups, but by late adulthood telomeres are longer in women than in men, and longer in European Americans than in African Americans (Aviv, 2011). There are many possible causes, but cellular-

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Stop the Clock?

Many scientists, as well as older people, seek to extend life. Those who restrict their calories may be extreme, but millions eat special foods (blueberries, red wine, fish oil?) or take certain drugs (sirtuins, rapamycin, resveratrol?) to extend life.

All the theories of aging, and all the research on genes, cells, calorie restriction, foods, drugs, antioxidants, and so on, have not yet led to any sure way to postpone death. Scientists are following numerous leads because many are convinced that something will slow aging.

For instance, a team of researchers traces about half of all adult cognitive decline to three specific diseases (Alzheimer’s disease, vascular disease, and Lewy body disease—

But the opposing perspective is that anti-

For example, the oldest well-

Further, is it ethical to strive for increased longevity for wealthy 80-

Many worry that by extending life, nations are adding medical costs to society. Currently, the U.S. health benefit for the aged of any income—

THINK CRITICALLY: Are anti-

Further, unconscious prejudice may be fueling the efforts to extend life. Compared to the average U.S. resident, older Americans tend to be more often of European than African ancestry, more often native-

Or is it ageist and prejudiced to suggest such a thing? Opposing perspectives.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 14.2

1. How is ageism similar to racism?

Ageism (the idea that age determines who you are) and racism (the idea that race determines who you are) are both forms of prejudice and stereotyping, which makes them social diseases that cause groups to treat each other based on superficial cues rather than on personal qualities. They both can lead to members of the stereotyped group accepting the stereotypes, to their own detriment. That can produce self-

Question 14.3

2. How is benevolent ageism harmful?

Ageism often seems complimentary or solicitous. However, the effects of ageism, whether benevolent or not, are insidious, seeping into and eroding the older person’s feelings of competence. The resulting self-

Question 14.4

3. What is elderspeak and how is it used?

Elderspeak, like baby talk, uses simple, short sentences, slower talk, higher pitch, louder volume, and frequent repetition. It may include patronizing terms such as “honey” and “dear,” or may use nicknames (e.g., Billy) instead of surnames (e.g., Mr. White).

Question 14.5

4. What is encouraging about the research on calorie restriction?

In several places, e.g., Okinawa, Denmark, Norway, Cuba, wartime occupation or other circumstances forced calorie reduction for almost everyone. While people were often hungry, fewer people died of disease.

Question 14.6

5. What is discouraging about the research on calorie restriction?

In the examples in the text, populations benefited when everyone ate less, particularly less meat; but in all these nations, once more food was available, people eagerly ate more and disease deaths rose again. Apparently, most humans choose some wear and tear in order to live the life they want.

Question 14.7

6. Regarding maximum and average life span, should both, neither, or only one be extended?

Answers will vary, but one might question whether it is ethical to strive for increased longevity for wealthy 80-

Question 14.8

7. What is the connection between telomeres and the Hayflick limit?

The Hayflick limit is the point at which the telomere (which becomes shorter with each cell duplication) is gone, duplication stops, and the creature dies.

Question 14.9

8. Why might a society consider it harmful for people to live past a certain age?

Many worry that by extending life, nations are adding medical costs to society and that any lengthening of life will result in less public money for schools, colleges, and health care for those under age 65. Further, the effort to extend life spans may disproportionately favor European American, Protestant Christian, higher-