Selective Optimization with Compensation

How does a person cope with senescence without succumbing to ageism? The answer, already mentioned in Chapter 12, is to choose (select) to specialize (optimize), using effective strategies (compensation). Here we stress the varied source of those strategies: from the individual, from the community, or from medicine.

Accordingly, we now provide three examples. In one (sex), personal thinking and behavior is effective; in another (driving), community laws and practices are crucial; and in the third (diseases), medical measures compensate for bodily changes.

Personal Compensation: Sex

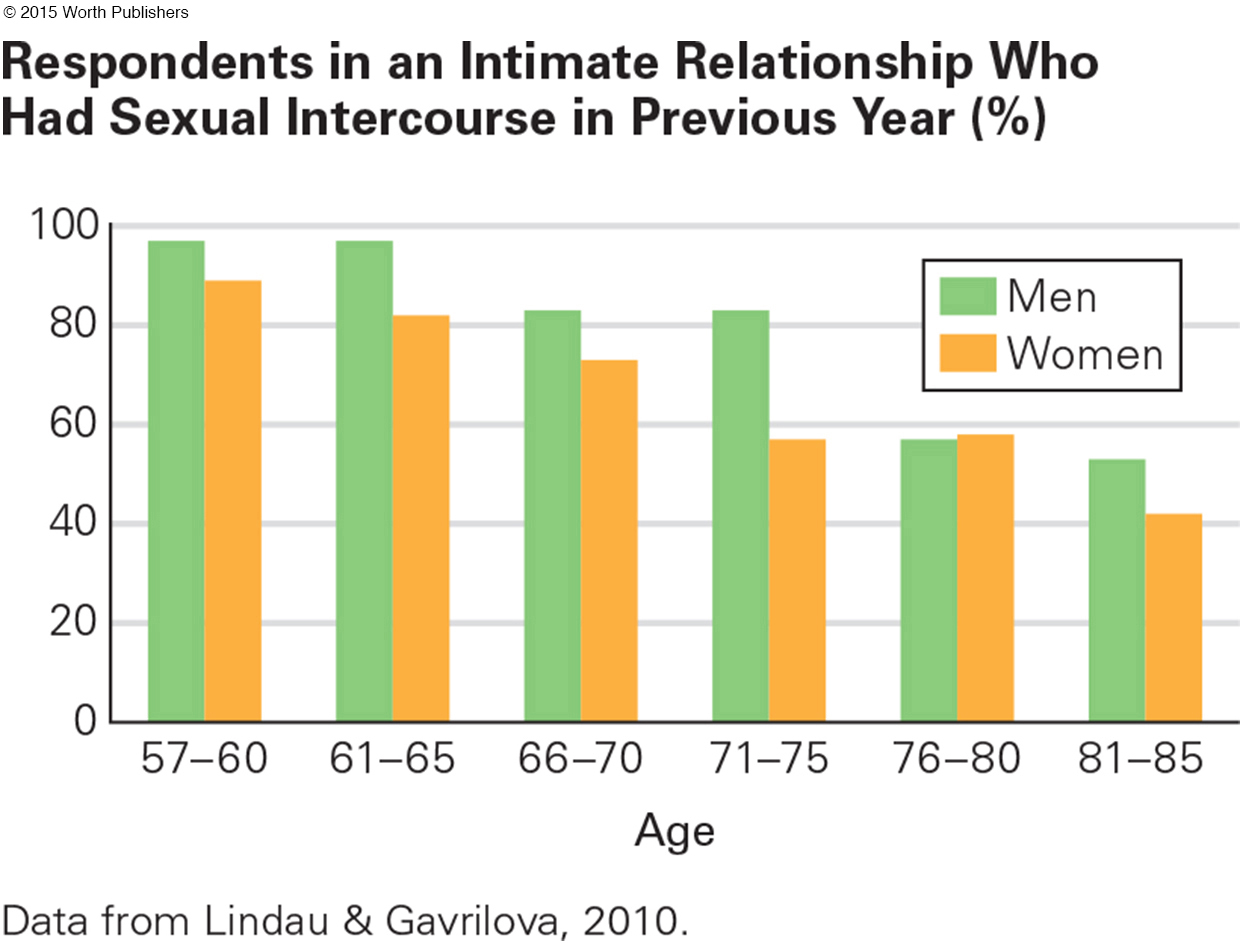

Most people are sexually active throughout adulthood. Some continue to have intercourse long past age 65 (Lindau & Gavrilova, 2010) (see Figure 14.5), but generally intercourse becomes less frequent and sometimes stops completely. Nonetheless, sexual satisfaction often increases after middle age (Heiman et al., 2011). How can that be?

Question 14.10

OBSERVATION QUIZ

What are the male–

Overall, older men are about 15 percent more likely to be sexually active than older women. Why? One explanation is that, among this cohort, brides were about five years younger than grooms, so some of those older married women had partners who were no longer “sexually active.” Another possibility is that, just as the high school students described in Chapter 1, men are still more likely to brag and women to demur—

Compensation for diminished arousal results from both thinking and behavior.

Many older adults reject the idea that intercourse is the only, or best, measure of sexual activity. Instead, cuddling, kissing, caressing, desiring, and fantasizing become more important. To optimize, they do more of these (Chao et al., 2011).

A five-

A CASE TO STUDY

Should Older Couples Have More Sex?

Sexual needs and interactions vary extremely from one person to another, so no single case illustrates general trends. Further, questionnaires and physiological measures designed for young bodies may be inappropriate for the aged. Accordingly, two researchers studied elderly sex using a method called grounded theory.

They found 34 people (17 couples, aged 50 to 86, married an average of 34 years), interviewing each privately and extensively. They read and reread all the transcripts, tallying responses and topics by age and gender (that was the grounded part). Then they analyzed common topics, interpreting trends (that was theory).

They concluded that sexual activity is more a social construction than a biological event (Lodge & Umberson, 2012). All their cases said that intercourse was less frequent with age, including four couples for whom intercourse stopped completely because of the husband’s health. Nonetheless, more respondents said that their sex life had improved than said it deteriorated (44 percent compared to 30 percent).

Surprisingly, those 44 percent were more likely to be over age 65 than middle-

One woman said:

All of a sudden, we didn’t have sex after I got skinny. And I couldn’t figure that out . . . I look really good now and we’re not having sex. It turns out that he was going through a major physical thing at that point and just had lost his sex drive . . . I went through years thinking it was my fault.

[Irene, quoted in Lodge & Umberson, 2012, p. 435]

The authors theorize that “images of masculine sexuality are premised on high, almost uncontrollable levels of penis-

Thus, when middle-

I think the intimacy is a lot stronger . . . more often now we do things like holding hands and wanting to be close to each other or touch each other. It’s probably more important now than sex is.

[Jim, quoted in Lodge & Umberson, 2012, p. 438]

An older woman said her marriage improved because

We have more opportunities and more motivation. Sex was wonderful. It got thwarted, with . . . the medication he is on. And he hasn’t been functional since. The doctors just said that it is going to be this way, so we have learned to accept that. But we have also learned long before that there are more ways than one to share your love.

[Helen, quoted in Lodge & Umberson, 2012, p. 437]

The next cohort of older adults may have other attitudes; the male/female and midlife/older differences evident with these 17 couples may not apply. These cases do suggest, however, that selective optimization with compensation is possible.

Social Compensation: Driving

In a life-

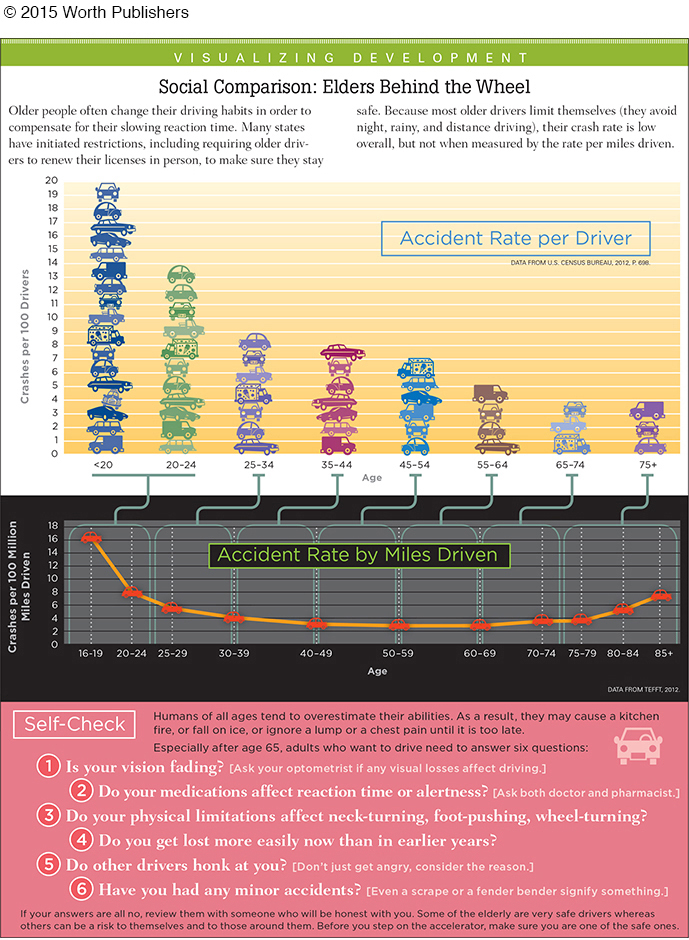

With age, reading road signs takes longer, turning the head becomes harder, reaction time slows, and night vision worsens. The elderly compensate: Many drive slowly and reduce driving in the dark.

However, relying on each older person’s judgment as to whether to stop driving is foolhardy, because the culture connects driving a car with pride and independence. Of course, the elderly hate to quit; it destroys their freedom. Consequently, many older drivers contend that their critics are ageist, not that they are accurate (Satariano et al., 2012). A family conflict occurs when adult children take car keys from an elderly parent.

It is no wonder that many elders insist they are good drivers and resent age-

The problem begins with license renewal. Some jurisdictions require only a mailed form and a check. Others require a written test about stop signs and parking and/or reading large letters on a well-

A national panel recommends every renewal include simulated driving, with the applicant seated with a steering wheel, accelerator, and brakes in front of a video (Staplin et al., 2012). The results of this test allow some 80-

Beyond retesting, there is much else that societies can do. Accidents would be reduced for every driver if larger-

Another society-

Medical Compensation: Survival

primary aging

The universal and irreversible physical changes that occur in all living creatures as they grow older. Primary aging is inevitable, programmed for each species.

secondary aging

The specific physical illnesses or conditions that become more common with aging but are caused by health habits and other influences that vary from person to person.

Gerontologists distinguish between primary aging, which involves universal changes that occur with the passage of time, and secondary aging, which are the consequences of particular inherited weaknesses, chosen health habits, and environmental conditions. Am I sick because I am old, or because of bad choices?

The benefits of modern medicine, based on science not custom, are obvious. In earlier centuries, people avoided hospitals and doctors. Some medical measures made people sicker, such as blood-

One obvious example is in childbirth. For centuries medical intervention (including blood-

Similar, although less dramatic, results occur in late adulthood. Each year in the United States, 16 percent of those age 65 and older are admitted to a hospital. No longer is that usually a death sentence; almost all recover quickly and go back home. The average hospital stay for those age 65 and older is only 6 days (National Center for Health Statistics, 2014).

compression of morbidity

A shortening of the time a person spends ill or infirm before dying, accomplished by postponing illness.

Modern medicine slows down primary aging and prevents secondary aging. That has doubled the life span in the past century. The goal now is compression of morbidity, which means fewer years (compression) of disability (morbidity) before death, adding “life to years, not years to life.” That goal was highlighted by the United Nations in 2002 and endorsed by every developed nation ( Walker, 2015).

Ideally, a person is in good health for decades after age 65, and then, within a few days or months, develops serious illnesses that lead to death. Medical research has discovered which personal habits, drugs, therapies, and/or surgeries reduce frailty for almost every disease and condition until that final episode.

The World Health Organization and many experts recognize that disability is the result of person–

HEART DISEASE Primary aging causes a slowdown of the heart rate as the vascular network becomes less flexible (blood pressure rises). That increases the risk of stroke and heart attack. Secondary aging—

Although medical research, beginning with the Framingham Heart Study, has discovered many aspects of secondary aging that harm the heart, adults overall are probably as vulnerable to heart disease as they were 50 years ago. To be specific, although far fewer adults smoke, far more are obese.

However, medical measures have targeted primary aging with great success. The heart disease death rate is lower for every age and gender group, dramatically apparent in the elderly. For example, cardiovascular deaths of 64-

Some of this reduction is in bypass surgery, pacemakers, and in healthier eating and exercising after a heart attack. Further, one medical measure to halt primary aging and heart deaths is the reduction of hypertension (high blood pressure), a problem for more than two-

Even doctors did not realize the danger of hypertension 50 years ago. Now, about half of all adults (especially older ones) with hypertension refuse treatment.

Men are less likely to take medication for hypertension than women, with rates of uncontrolled hypertension (age-

One reason for their “medication non-

Science continues to find new ways to cure or prevent diseases, discovering age differences in how people respond. Some measures that work for adults are not effective for children, and the very old need particular treatment guidelines. For example, after age 80, medication is not recommended until hypertension reaches 150/90, not 140/90 (Kithas & Supiano, 2015).

osteoporosis

Fragile bones that result from primary aging, which makes bones more porous, especially if a person is at genetic risk.

OSTEOPOROSIS Compression of morbidity is also dramatic in osteoporosis (fragile bones). Primary aging makes bones more porous, as cells that build bone (osteoblasts) are outnumbered by cells that reabsorb bone (osteoclasts) (Rachner et al., 2011). Osteoporosis is especially common in underweight women with European ancestry, although men and people of other ethnic groups experience it.

Because of osteoporosis, a fall that would have merely bruised a young person may result in a broken wrist, hip, or spine, starting a cascade of medical problems. Fractures once led to death for 10 percent of osteoporosis sufferers within a year, with a broken hip “a leading cause of morbidity and excess mortality among older adults” (MMWR, March 31, 2000). Half of those with broken hips never walked again. Immobility causes body systems to deteriorate, spreading, not compressing, morbidity.

Note the 2000 date. A more recent report: “In the 21st century, osteoporosis, a disease once considered an inevitable consequence of aging, is both diagnosable and treatable” (Black et al., 2012, p. 2051). Medical compression of morbidity has occurred.

Early diagnosis via a bone density test (not available a few decades ago) detects bone weakening long before the first fracture. Doctors advise prevention, with weight-

Because a focus on chronic conditions is relatively new and treatment of osteoporosis is newer yet, scientists do not know the consequences of ingesting preventive drugs over many years. The data suggest caution (Black et al., 2012), because drugs that prevent one problem may eventually cause another. Nonetheless, the 44 million people over age 50 in the United States who have weak bones need not experience the disabling breaks that those with osteoporosis once did. That is compression of morbidity.

Hearts and bones are only two examples. For almost every disease and condition, morbidity can be compressed by all three of the types of measures detailed here—

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 14.11

1. How can couples continue to have satisfying sex lives in old age?

Research suggests that couples should do more cuddling, kissing, caressing, desiring, and fantasizing as intercourse becomes less frequent.

Question 14.12

2. What is the age-

Most people are sexually active throughout adulthood. Some continue to have intercourse long past age 65, but generally intercourse becomes less frequent and sometimes stops completely. However, sexual satisfaction often increases after middle age.

Question 14.13

3. How should it be decided whether or not an elderly person should drive?

New tests need to be designed that test judgment, reaction time, and peripheral vision. A national panel recommends simulated driving via a computer and video screen, with the prospective driver seated with a steering wheel, accelerator, and brakes. The results of this test could allow some 80-

Question 14.14

4. How does heart disease illustrate both primary and secondary aging?

Primary aging: With age the heart pumps more slowly and the vascular network is less flexible, increasing the risk of stroke and heart attack. Secondary aging: A high allostatic load can increase the likelihood of heart disease.

Question 14.15

5. What is the continued impact of the Tuskegee study?

One lasting effect of the Tuskegee study is mistrust among African American men of doctors’ prescriptions of medications. That is said to be one reason heart disease kills more African American men, at younger ages, than African American women or men of other ethnic groups.

Question 14.16

6. Why would a broken hip make death more likely?

A fall that would merely bruise a young person may result in a broken hip, starting a cascade of medical problems. Immobility causes body systems to deteriorate, which explains why fractures once led to death for 10 percent of osteoporosis sufferers within a year, with a broken hip “a leading cause of morbidity and excess mortality among older adults.”

Question 14.17

7. How does osteoporosis illustrate compression of morbidity?

Before the twenty-