Friends and Relatives

Many of the older adults in Video: Active and Healthy Aging: The Importance of Community frequent senior centers for continual social contact, and some benefit from volunteering.

Companions are particularly important in old age. As socio-

For most of the elderly, however, negative relationships have been abandoned, and positive ones remain. Bonds formed over the years allow people to share triumphs and tragedies with others who understand and appreciate. Siblings, old friends, and spouses are ideal convoy members.

Long-Term Partnerships

For many of the current cohort of elders, their spouse is the central convoy member, a buffer against the problems of old age. Even more than other social contacts, including friends and children, a spouse is protective of health (Wong & Waite, 2015). All the research finds that married older adults are healthier, wealthier, and happier than unmarried people their age.

Mutual interaction is crucial: Each healthy and happy partner improves the other’s well-

A lifetime of shared experiences—

Older couples have learned how to disagree, considering conflicts to be discussions, not fights. I know one example personally.

Irma and Bill are both politically active, proud parents of two adult children, devoted grandparents, and informed about current events. They seem happily married and they cooperate admirably when caring for their 2-

However, they vote for opposing candidates for president. I was puzzled until Irma explained: “We sit together on the fence, seeing both perspectives, and then, when it’s time to vote, Bill and I fall on opposite sides.” I can predict who will fall on which side, but for them, the discussion is productive. Their long-

Outsiders might judge many long-

One crucial factor is coping with challenges of child rearing, home ownership, economic crises, and so on. The importance of past sharing, rather than each living independent lives, is suggested by research that finds that older husbands and wives with mutual close friends are more likely to help each other if special needs arise (Cornwell, 2012).

Given the importance of relationship building over the life span, it is not surprising that elders who are disabled (e.g., have difficulty walking, bathing, and so on) are less depressed and anxious if they are in a close marital relationship (Mancini & Bonanno, 2006). A couple together can achieve selective optimization with compensation.

For example, I know a man whose memory is fading. He is married to a woman whose legs are so weak that she has difficulty getting out of bed. If either had been alone, he or she would need extensive care. However, the husband helps the wife move, and she keeps track of what needs to be done—

Relationships with Younger Generations

In past centuries, many adults died before their grandchildren were born. For 10-

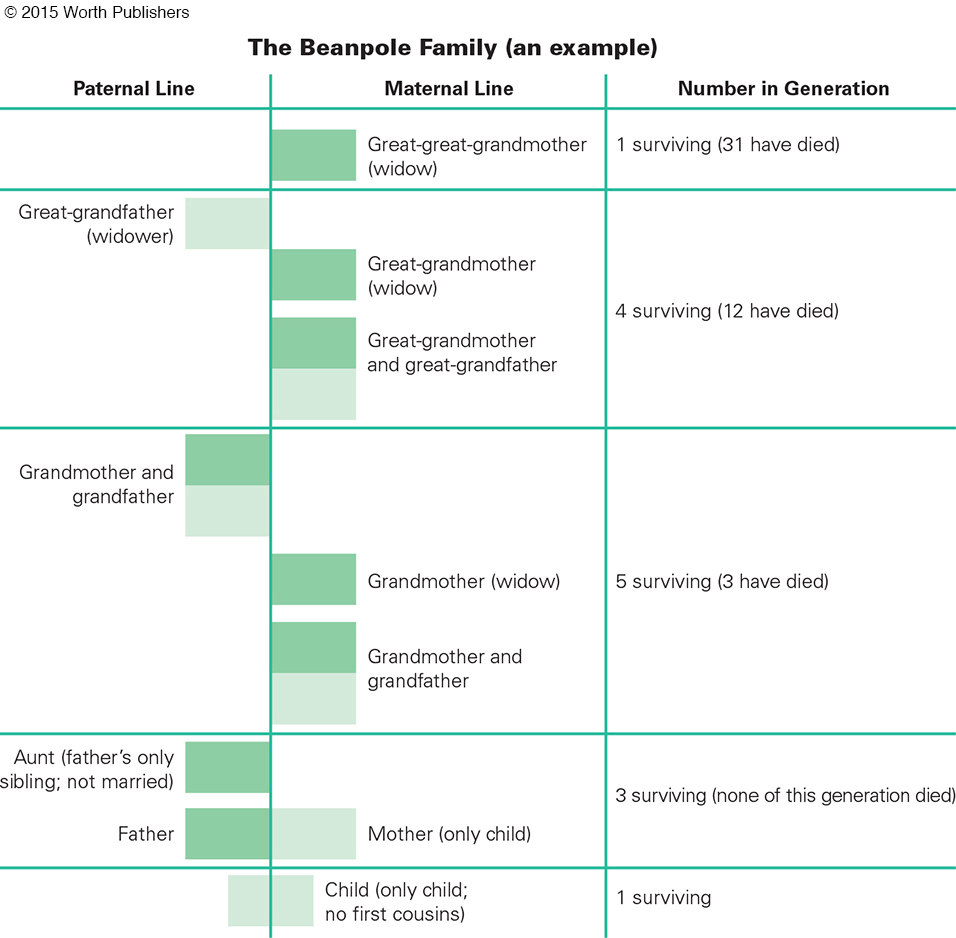

Since the average couple now has fewer children, the beanpole family, with multiple generations but with only a few members at each level, is becoming more common (Murphy, 2011) (see Figure 15.8). Some children have no cousins, brothers, or sisters but a dozen elderly relatives.

filial responsibility

The obligation of adult children to care for their aging parents.

INTERGENERATIONAL RELATIONSHIPS As you remember, familism prompts family caregiving among all the relatives. One norm is filial responsibility, the obligation of adult children to care for their aging parents. This is a value in every nation, with some variation by culture (Saraceno, 2010).

As a value, filial responsibility is strongest in Asia, but in practice, some scholars find Asians less likely to care for elderly parents than in Western cultures. For example, a survey in China found that half of adult children saw their parents only once a year or less (Kim et al., 2015).

Familism works down the generations, not just up. Many elders believe the older generations should help the younger ones. Specifics vary by culture. When the government provides more help for the aged (housing, pensions, and so on), the generations are more involved with each other, not less (Herlofson & Hagestad, 2012). The reason is that emotional support flows most easily when basic care is less crucial.

As you also remember, older adults do not want to move in with younger generations, doing so only if poverty and frailty require it. Especially in the United States, every generation values independence. That is why, after midlife and especially after the death of their own parents, elders are less likely to agree that children should provide substantial care for their parents and more likely to strive to be helpful to their children.

Complications and surprises regarding parent–

Although elderly people’s relationships with members of younger generations are usually positive, they can also include tension and conflict. In some families intergenerational respect and harmony abound; whereas in others, family members refuse to see each other. Each culture and each family has patterns and expectations regarding interactions between generations (Herlofson & Hagestad, 2011).

A good relationship with successful grown children enhances a parent’s well-

Some conflict is common, as is some mutual respect. Indeed, both within families and within cultures, ambivalence is becoming recognized as a common intergenerational pattern (Connidis, 2015), with mixed feelings in every generation.

Extensive research finds many factors that affect intergenerational relationships:

Assistance arises from both need and ability to provide.

Frequency of contact is more dependent on geographical proximity than affection.

Love is influenced by childhood memories.

Sons feel stronger obligation; daughters feel stronger affection.

National norms and policies can nudge family support, but they do not create it.

GRANDPARENTS AND GREAT-

As with parents and children, specifics of the grandparent–

Brian and Brianna are twins and are turning 13 years old this coming June. Over the spring break my family celebrated my grandmother’s 80th birthday and I overheard the twins’ talking about how important it was for them to still have grandma around because she was the only one who would give them money if they really wanted something their mom wasn’t able to give them. . . . I lashed out . . . how lucky we were to have her around and that they were two selfish little brats. . . . Now that I am older, I learned to appreciate her for what she really is. She’s the rock of the family and “the bank” is the least important of her attributes now.

[Giovanna, personal communication]

Grandparents fill one of four roles:

Remote grandparents (sometimes called distant grandparents) are emotionally distant from their grandchildren. They are esteemed elders who are honored, respected, and obeyed, expecting to get help whenever they need it.

Page 559Companionate grandparents (sometimes called “fun-

loving” grandparents ) entertain and “spoil” their grandchildren—especially in ways that the parents would not. Involved grandparents are active in the day-

to- day lives of their grandchildren. They live near them and see them often. Surrogate parents raise their grandchildren, usually because the parents are unable or unwilling to do so.

Currently, in developed nations, most grandparents are companionate, partly because all three generations expect them to be companions, not authorities. Contemporary elders usually enjoy their own independence. They provide babysitting and financial help but not advice or discipline (May et al., 2012).

As you remember from Chapter 13, in skipped generation families, grandparent health and happiness are sometimes sacrificed when the grandparent takes on the stresses and responsibilities of the parent role. Usually such grandparents are relatively young, far more often age 50 than 70. Often full parental responsibility ages them quickly.

A middle ground is best. Just as too much responsibility impairs health and happiness, too little may be harmful as well. One Australian study focused on grandparents whose children prevented contact with the grandchildren.

For example, one reported this conversation with her daughter:

She said: “You’ve never been a good mother, only when I was little”. I said: “now that is ridiculous and you know that is ridiculous”. She said: “you be quiet and listen to what I have to say, what I have to tell you now. . . I never want to see or hear from you the rest of your life” . . . I said: “I have fought hard. I have provided for both of your children. I’ve done all that I can to help you and [son-

[Sims & Rofail, 2014, p. 3]

Another grandmother in the same study first was thrilled with her grandchildren and then despondent when she could no longer see them.

It was so enjoyable and now to think about it brings me to tears . . . this breaks our hearts , , , the consequence of this is that I have had issues of anxiety and depression, none of which I had previously and now I have been diagnosed with a severe heart problem, cardiomyopathy . . . this is more than I can bear—

[Sims & Rofail, 2014, pp. 4–

In Video: Grandparenting, several individuals discuss their close, positive attachments to their grandchildren.

Sometimes past parent–

Adults change over time, even in late adulthood. A grandparent can become less, or more, strict, following parental rules that differ from past practices. As with every human relationship, mutual compromise and explicit communication is essential.

Relationships with the younger generation promote the emotional and physical well-

being of the older generation. Not only heart problems, high blood pressure, and sleepless nights, but even life itself is affected by social interaction (Paúl, 2014).

One of the realities of human development that appears in study after study is that family connections are pivotal for optimal growth, from pregnancy (when relatives help keep the expectant mother healthy and drug-

Friendship

Friendship networks typically are reduced with each decade. Emerging adults tend to have the most friends on average. By late adulthood, the number of people considered friends is notably smaller (Wrzus et al., 2013). Added to this normal shrinkage are two circumstances: Some older friends die, and retirees usually lose contact with work friends.

Family friends tend to be the most loyal. Elders are healthiest if some family friends are among their closest social circle. Yet if the circle includes only relatives, and not several non-

As explained in Chapters 11 and 13, each younger cohort is more often unmarried. In the United States, the never-

Further, more middle-

Not necessarily. Recent data find that elders who never married are usually quite content, not lonely. Some of them have partners, of the same sex or other sex, and are cohabiting or living apart together, seemingly just as happy as traditionally married people (Brown & Kawamura, 2010). Further, having a smaller friendship circle is not a problem if a person has at least a few close friends—

People who have spent years without a romantic partner usually have close friendships, meaningful activities, and social connections that keep them busy and happy. The crucial factor is having friends—

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 15.18

1. What is the usual relationship between older adults who have been partners for decades?

Outsiders might judge many long-

Question 15.19

2. Who benefits most from relationships between older adults and their grown children?

Familism prompts family caregiving among all the relatives. One manifestation is filial responsibility, the obligation of adult children to care for their aging parents. This is a value in every nation, stronger in some cultures than in others. As family size shrinks, many older parents continue to feel responsible for their grown children. Both generations benefit from their relationship.

Question 15.20

3. Which type of grandparenting seems to benefit both generations the most?

Companionate grandparents, who are fun, kind, and generous playmates for grandchildren and who provide babysitting and financial support for the family while still having their own independent lives, seem to benefit both generations the most.

Question 15.21

4. Why do older people tend to have fewer friends as they age?

Some older friends die, and retirement usually means losing contact with most work friends.

Question 15.22

5. Why are people who have never married not likely to be lonely and sick?

Recent data find that elders who never married are usually quite content, not lonely. Some of them have partners, of the same sex or other sex, and are cohabiting or living apart together, seemingly just as happy as traditionally married people. Further, having a smaller friendship circle is not a problem if a person has at least a few close friends—

Question 15.23

6. How do demographic changes affect family relationships?

When demographics change, filial responsibility is impacted. Some people still romanticize elder care, believing that frail older adults should live with their caregiving children. That assumption worked when the demographic pyramid meant that each surviving elder had many descendants, but it may overburden beanpole families.