Theories of Human Development

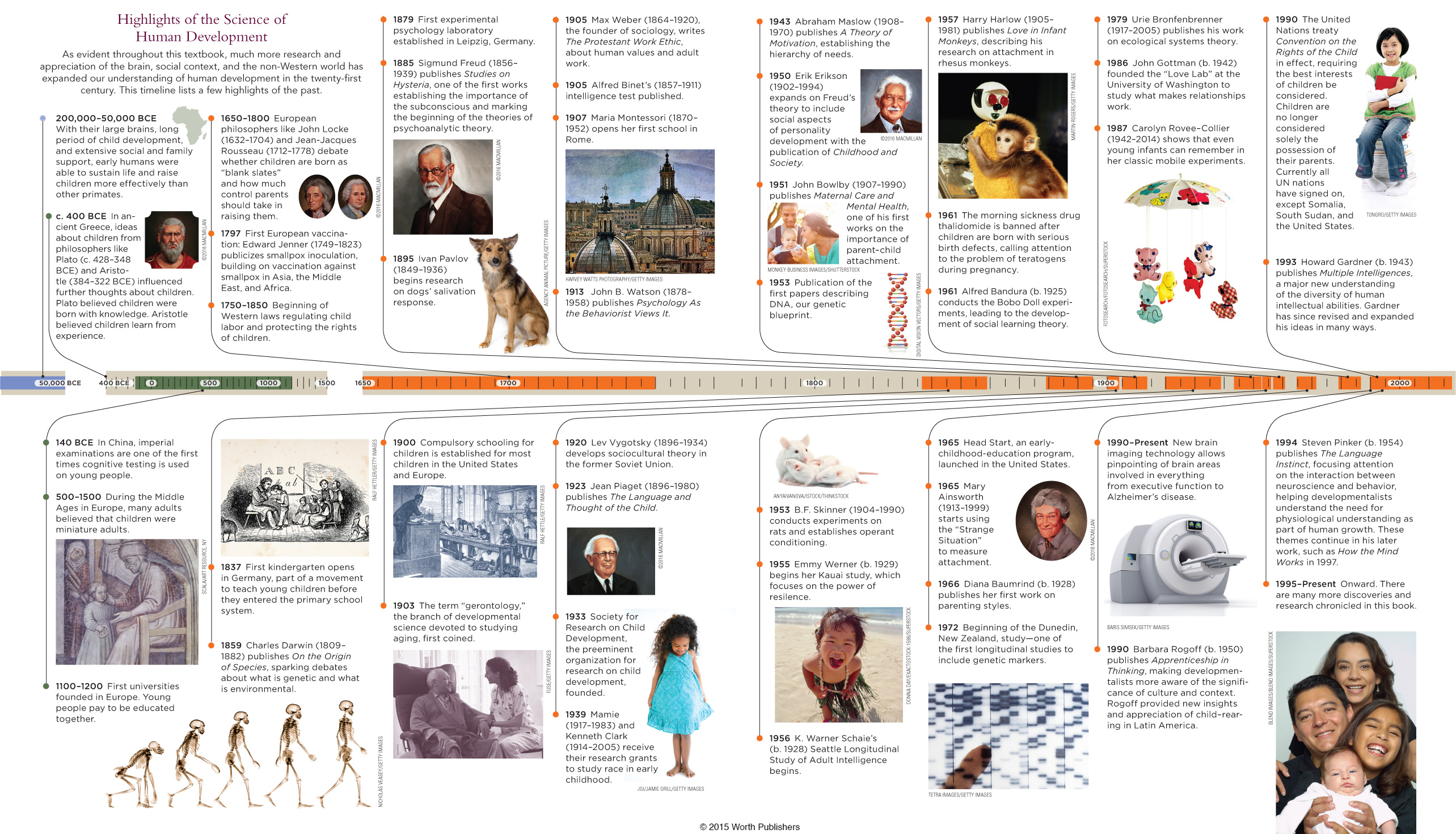

As you read earlier in this chapter, the scientific method begins with observations, questions, and theories (Step 1). That leads to specific hypotheses that can be tested (Step 2). A theory is a comprehensive and organized explanation of many phenomena; a hypothesis is more limited and may be proven false. Theories are generalities; hypotheses are specific.

developmental theory

A group of ideas, assumptions, and generalizations that interpret and illuminate thousands of observations about human growth. A developmental theory provides a framework for explaining the patterns and problems of development.

Theories sharpen perceptions and organize the thousands of behaviors we observe every day. Each developmental theory is a systematic statement of principles and generalizations, providing a framework for understanding how and why people change over the life span.

Imagine building a house from a heap of lumber, nails, and other materials. Without a plan and workers, the heap cannot become a home. Likewise, observations of human development are raw materials, but theories put them together. Kurt Lewin (1943) once quipped, “Nothing is as practical as a good theory.”

Dozens of such theories appear throughout this text. The five theories about to be explained are chosen because each provides a comprehensive, influential, and somewhat distinctive view of human development. Many social scientists are strongly influenced by other theories, as you will see.

Psychoanalytic Theory

psychoanalytic theory

A theory of human development that holds that irrational, unconscious drives and motives, often originating in childhood, underlie human behavior.

Inner drives and motives are the foundation of psychoanalytic theory. These basic underlying forces are thought to influence every aspect of thinking and behavior, from the smallest details of daily life to the crucial choices of a lifetime.

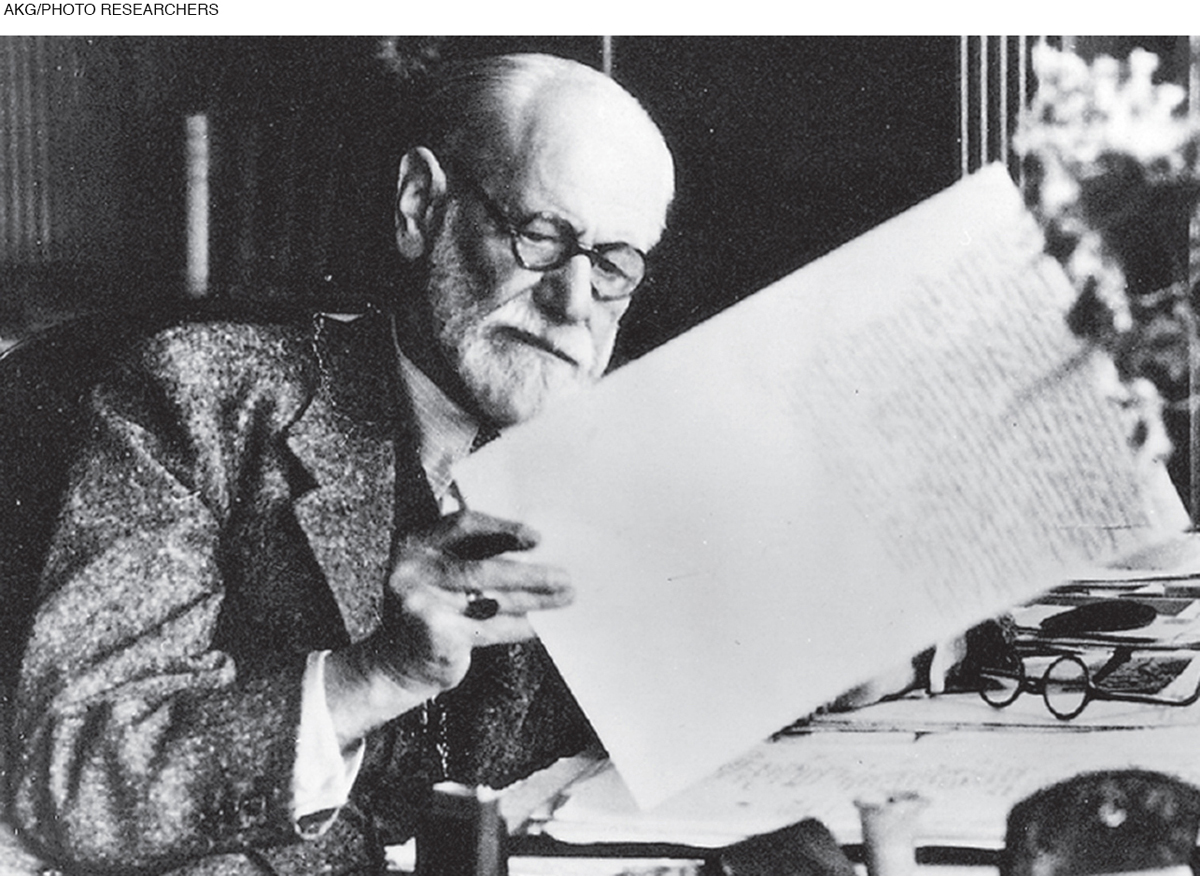

FREUD’S STAGES Psychoanalytic theory originated with Sigmund Freud (1856–

According to Freud, development in the first six years occurs in three stages, each characterized by sexual pleasure centered on a particular part of the body. Infants experience the oral stage because their erotic body part is the mouth, followed by the anal stage in early childhood, with the focus on the anus. In the preschool years (the phallic stage), the penis becomes a source of pride and fear for boys and a reason for sadness and envy for girls.

In middle childhood comes latency, a quiet period that ends with the genital stage at puberty. Freud thought that the genital stage continued throughout adulthood, which makes him the most famous theorist who thought that development stopped after puberty (see Table 1.4). As you remember, this assumption is no longer held by developmentalists.

Freud maintained that at each stage, sensual satisfaction (from the mouth, anus, or genitals) is linked to developmental needs, challenges, and conflicts. How people experience and resolve these conflicts—

ERIKSON’S STAGES Many of Freud’s followers became famous theorists themselves. The most notable for our study of human development was Erik Erikson (1902–

Erikson named two polarities at each stage (which is why the word versus is used in each), but he recognized that many outcomes between these opposites are possible (Erikson, 1993). For most people, development at each stage leads to neither extreme.

For instance, the generativity-

Erikson, like Freud, believed that adult problems echo childhood conflicts. For example, an adult who cannot form a secure, close relationship (intimacy versus isolation) may not have resolved the crisis of infancy (trust versus mistrust). However, Erikson’s stages differ significantly from Freud’s in that they emphasize family and culture, not sexual urges. He called his theory epigenetic, partly to stress that genes and biological impulses are powerfully influenced by the social environment.

| Approximate Age | Freud (Psychosexual) | Erikson (Psychosocial) |

| Birth to 1 year |

Oral Stage The lips, tongue, and gums are the focus of pleasurable sensations in the baby’s body, and sucking and feeding are the most stimulating activities. |

Trust vs. Mistrust Babies either trust that others will care for their basic needs, including nourishment, warmth, cleanliness, and physical contact, or develop mistrust about the care of others. |

| 1– |

Anal Stage The anus is the focus of pleasurable sensations in the baby’s body, and toilet training is the most important activity. |

Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt Children either become self- |

| 3– |

Phallic Stage The phallus, or penis, is the most important body part, and pleasure is derived from genital stimulation. Boys are proud of their penises; girls wonder why they don’t have one. |

Initiative vs. Guilt Children either want to undertake many adultlike activities or internalize the limits and prohibitions set by parents. They feel either adventurous or guilty. |

| 6– |

Latency Not really a stage, latency is an interlude during which sexual needs are quiet and children put psychic energy into conventional activities like schoolwork and sports. |

Industry vs. Inferiority Children busily learn to be competent and productive in mastering new skills or feel inferior, unable to do anything as well as they wish they could. |

| Adolescence |

Genital Stage The genitals are the focus of pleasurable sensations, and the young person seeks sexual stimulation and sexual satisfaction in heterosexual relationships. |

Identity vs. Role Confusion Adolescents try to figure out “Who am I?” They establish sexual, political, and vocational identities or are confused about what roles to play. |

| Adulthood | Freud believed that the genital stage lasts throughout adulthood. He also said that the goal of a healthy life is “to love and to work.” |

Intimacy vs. Isolation Young adults seek companionship and love or become isolated from others, fearing rejection and disappointment. Generativity vs. Stagnation Middle- Integrity vs. Despair Older adults try to make sense out of their lives, either seeing life as a meaningful whole or despairing at goals never reached. |

Behaviorism

behaviorism

A theory of human development that studies observable behavior. Behaviorism is also called learning theory because it describes the laws and processes by which behavior is learned.

Another influential theory, behaviorism, arose in direct opposition to the psychoanalytic emphasis on unconscious, hidden urges (differences are described in Table 1.5). Behaviorists emphasize nurture, the specific responses from other people and the environment to whatever a developing person does.

| Area of Disagreement | Psychoanalytic Theory | Behaviorism |

| The unconscious | Emphasizes unconscious wishes and urges, unknown to the person but powerful all the same | Holds that the unconscious not only is unknowable but also may be a destructive fiction that keeps people from changing |

| Observable behavior | Holds that observable behavior is a symptom, not the cause— |

Looks only at observable behavior— |

| Importance of childhood | Stresses that early childhood, including infancy, is critical; even if a person does not even remember what happened, the early legacy lingers throughout life | Holds that current conditioning is crucial; early habits and patterns can be unlearned, reversed, if appropriate reinforcements and punishments are used |

| Scientific status | Holds that most aspects of human development are beyond the reach of scientific experiment; uses ancient myths, the words of disturbed adults, dreams, play, and poetry as raw material | Is proud to be a science, dependent on verifiable data and carefully controlled experiments; discards ideas that sound good but are not proven |

WATSON Early in the twentieth century, John B. Watson (1878–

Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-

[Watson, 1998, p. 82]

Many other psychologists, especially in the United States, agreed. They found that the unconscious motives and drives that Freud described were difficult (or impossible) to verify via the scientific method (Uttal, 2000). For instance, researchers discovered that, contrary to Freud’s view, the parents’ approach to toilet training did not determine a child’s later personality.

For every individual at every age, from newborn to centenarian, behaviorists have identified laws to describe how environmental responses shape what people do. All behavior—

conditioning

According to behaviorism, the processes by which responses become linked to particular stimuli and learning takes place. The word conditioning is used to emphasize the importance of repeated practice, as when an athlete conditions his or her body by training for a long time.

PAVLOV The specific laws of learning apply to conditioning, the processes by which responses become linked to particular stimuli.

Question 1.21

OBSERVATION QUIZ

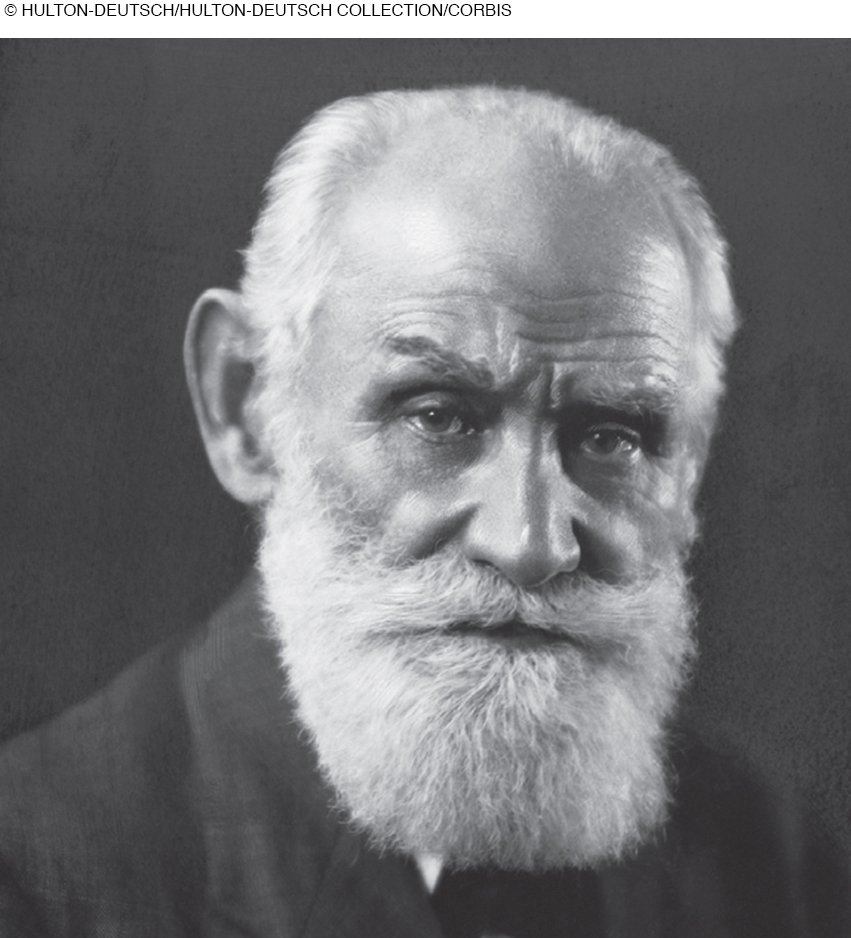

In appearance, how is Pavlov similar to Freud, and how do both look different from the other theorists pictured?

Both are balding, with white beards. Note also that none of the other theorists in this chapter have beards—

More than a century ago, Ivan Pavlov (1849–

Pavlov began by sounding a tone just before presenting food. After a number of repetitions of the tone-

operant conditioning

The learning process by which a particular action is followed by something desired (a reinforcer which makes the person or animal more likely to repeat the action) or by something unwanted (a punishment which makes the action less likely to be repeated). (Also called instrumental conditioning.)

SKINNER One influential North American behaviorist, B. F. Skinner (1904–

In operant conditioning (also called instrumental conditioning), animals (including humans) perform some action and then a response occurs. If the response is useful or pleasurable, the animal is likely to repeat the action; if the response is painful, the animal is not likely to repeat the action. In both cases, the animal has learned.

Pleasant consequences are sometimes called rewards, and unpleasant consequences are sometimes called punishments. Behaviorists hesitate to use those words, however, because what people think of as punishment can actually be a reward, and vice versa.

For example, how should a parent punish a child? Withholding dessert? Spanking? Not letting them play? Speaking harshly? If a child hates that dessert, being deprived of it is actually a reward, not a punishment. Another child might not mind a spanking, especially if he or she craves parental attention. For that child, the intended punishment (spanking) is actually a reward (attention).

Any consequence that follows a behavior and makes the person (or animal) likely to repeat that behavior is called a reinforcement, not a reward. Once a behavior has been conditioned, humans and other creatures will repeat it even if reinforcement occurs only occasionally. Similarly, an unpleasant response makes a creature less likely to repeat a certain action.

Almost all daily behavior, from combing your hair to joking with friends, is a result of past operant conditioning, according to behaviorists. Likewise, things people fear, from giving a speech to eating raw fish, are avoided because of past punishment.

This insight has many practical applications for human development. Early responses are crucial because children learn habits that endure. For instance, if parents want their child to share, and their baby offers them a gummy, half-

Video Activity: Modeling: Learning by Observation features the original footage of Bandura’s famous experiment.

According to behaviorism, people are never too old to learn. If an adult is afraid of speaking in public (a particular kind of social phobia, very common), then repeated reinforcement for talking (such as a professor praising a student’s question) could eventually lead to speeches before an audience.

social learning theory

An extension of behaviorism that emphasizes the influence that other people have over a person’s behavior. Even without specific reinforcement, every individual learns many things through observation and imitation of other people. (Also called observational learning.)

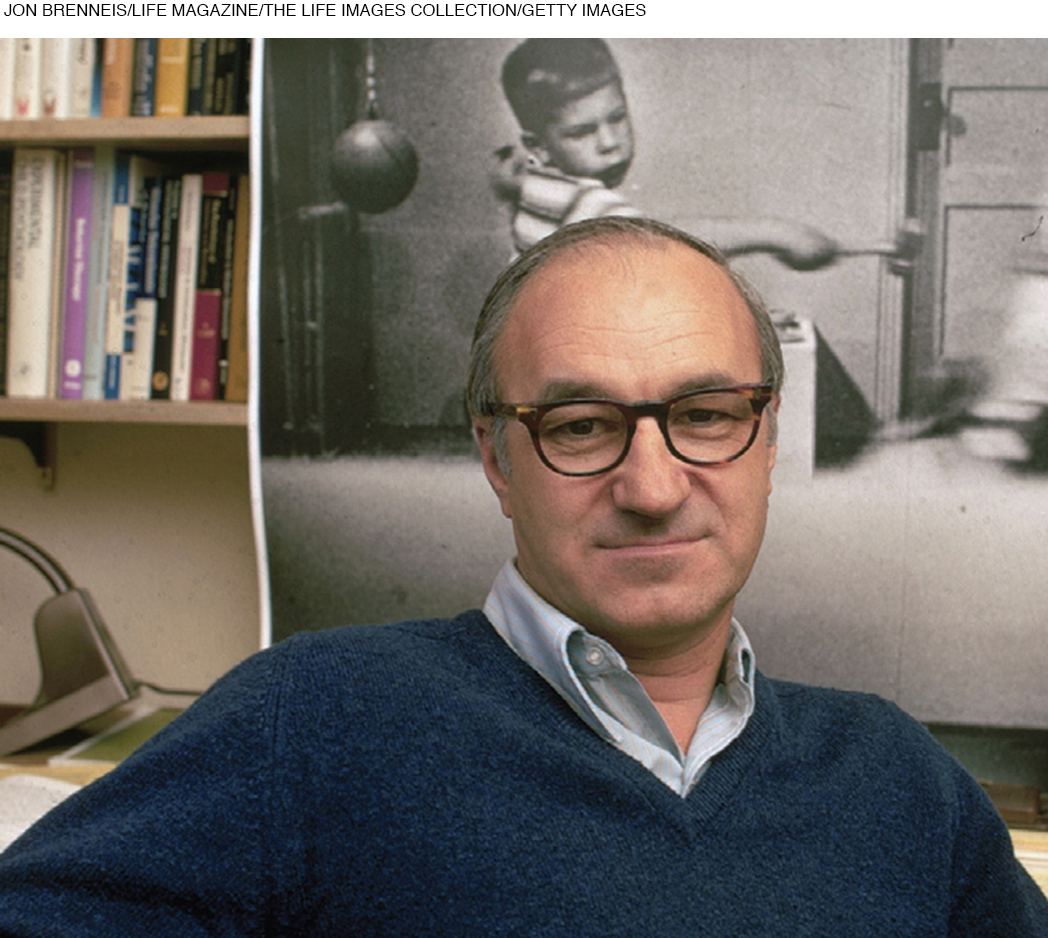

BANDURA A major extension of behaviorism is social learning theory, first described by Albert Bandura (b. 1925). This theory notes that, because humans are social beings, they learn from observing others, even without personally receiving any reinforcement (Bandura, 1977; 2006).

For example, many studies find that most children who witness domestic violence are influenced by it. As differential susceptibility and multi-

Later in adulthood, because of their past social learning, one man might slap his wife and spank his children, while his brother might be fearful and apologetic at home. Social learning taught them opposite lessons. A third brother might be more like a dandelion than an orchid, unaffected by past memories.

Cognitive Theory

cognitive theory

A theory of human development that focuses on changes in how people think over time. According to this theory, thoughts shape attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors.

In cognitive theory, each person’s ideas and beliefs are crucial. This theory has dominated psychology since about 1980 and has branched into many versions. The word cognitive refers not just to thinking but also to attitudes, beliefs, and assumptions.

The most famous cognitive theorist was Jean Piaget (1896–

From this work, Piaget developed the central thesis of cognitive theory: How people think (not just what they know) changes with time and experience, and then human thinking influences actions. Piaget maintained that cognitive development occurs in four major age-

| Age Range | Name of Period | Characteristics of the Period | Major Gains During the Period |

| Birth to 2 years | Sensorimotor | Infants use senses and motor abilities to understand the world. Learning is active; there is no conceptual or reflective thought. | Infants learn that an object still exists when it is out of sight (object permanence) and begin to think through mental actions. |

| 2– |

Preoperational | Children think magically and poetically, using language to understand the world. Thinking is egocentric, causing children to perceive the world from their own perspective. | The imagination flourishes, and language becomes a significant means of self- |

| 6– |

Concrete operational | Children understand and apply logical operations, or principles, to interpret experiences objectively and rationally. Their thinking is limited to what they can personally see, hear, touch, and experience. | By applying logical abilities, children learn to understand concepts of conservation, number, classification, and many other scientific ideas. |

| 12 years through adulthood | Formal operational | Adolescents and adults think about abstractions and hypothetical concepts and reason analytically, not just emotionally. They can be logical about things they have never experienced. | Ethics, politics, and social and moral issues become fascinating as adolescents and adults take a broader and more theoretical approach to experience. |

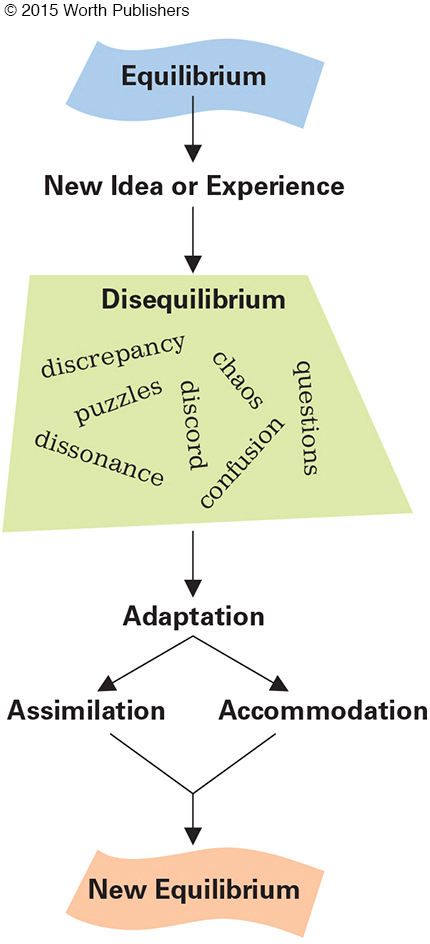

Intellectual advancement occurs lifelong because humans seek cognitive equilibrium, that is, a state of mental balance. An easy way (called assimilation) to achieve this balance is to interpret new experiences through the lens of preexisting ideas. For example, infants discover that new objects can be grasped in the same way as familiar objects; adolescents explain the day’s headlines as evidence that supports their existing worldviews; older adults speak fondly of the good old days as embodying values that should endure.

Sometimes, however, a new experience is jarring and incomprehensible. The resulting experience is one of cognitive disequilibrium, an imbalance that initially creates confusion. As Figure 1.10 illustrates, disequilibrium leads to cognitive growth because it forces people to adapt their old concepts (called accommodation). Current research supports the idea that learning is more likely to occur if it took some effort to achieve (Brown et al., 2014).

Another influential cognitive theory, called information processing, is not a stage theory but rather provides a detailed description of the steps of cognition, with attention to perceptual and neurological processes. This theory is especially useful in understanding thinking processes in middle childhood and late adulthood, as you will see in Chapters 7 and 14.

Many researchers, in addition to those influenced by information-

Humanism

humanism

A theory that stresses the potential of all humans, who have the same basic needs, regardless of culture, gender, or background.

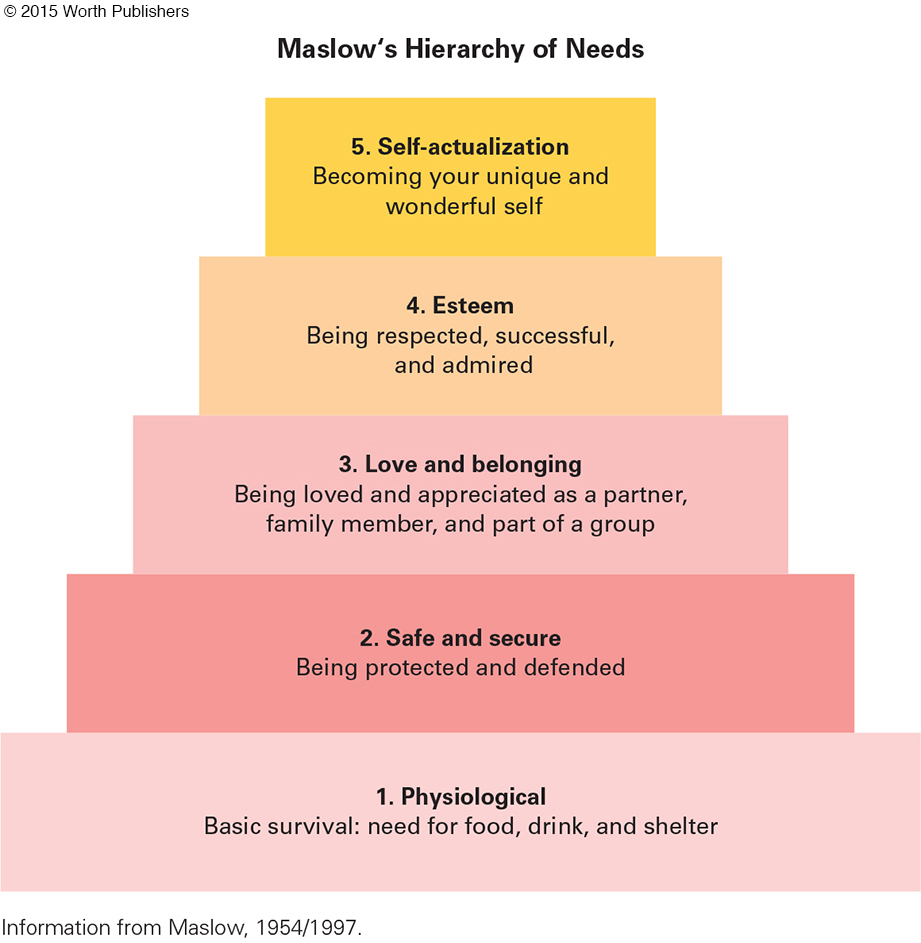

Many scientists are convinced that there is something hopeful, unifying, and noble in the human spirit, something often ignored by psychoanalytic theory and by behaviorism. The limits of those two major theories were especially apparent to Abraham Maslow (1908–

Physiological: needing food, water, warmth, and air

Safety: feeling protected from injury and death

Love and belonging: having loving friends, family, and a community

Esteem: being respected by the wider community as well as by oneself

Self-

actualization: becoming truly oneself, fulfilling one’s unique potential

At the final level, self-

Maslow contended that everyone must satisfy each lower level before moving higher. A starving man, for instance, may risk his life to secure food (level 1 precedes level 2), or an unloved woman might not care about self-

Although humanism does not postulate stages, a developmental application of this theory is that satisfying childhood needs allows later growth. Thus, when babies cry in hunger, someone should feed them because their basic needs (level 1) should be met. People may become thieves or even killers, unable to reach their potential, if they were unsafe (level 2) or unloved (level 3) as children.

This theory is prominent among medical professionals because they realize that pain can be physical (the first two levels) or social (the next two), and they are concerned that their focus on physical health might overlook the person’s higher needs (Brown et al., 2014).

A practicing general practitioner writes that Maslow’s hierarchy is “a useful reference tool,” although he accepts that most of what doctors do is at the lower levels of the pyramid (Dawlatly, 2014). Even the dying need love and belonging (family should be with them) and esteem (the dying need respect).

Evolutionary Theory

Charles Darwin’s basic ideas about evolution were first published 150 years ago (Darwin, 1859), but serious research on human development inspired by evolutionary theory is quite recent. According to this theory, nature works to ensure that each species does two things: survive and reproduce. Consequently, many human impulses, needs, and behaviors evolved to help humans survive and thrive over the past 100,000 years (Konner, 2010).

To understand human development, this theory contends, one needs to recognize what was adaptive thousands of years ago. For example, it is irrational that many people are terrified of snakes (which now cause less than one U.S. death in a million), but virtually no one fears automobiles (which cause more than one death in a hundred). Evolutionary theory suggests that the fear instinct evolved to protect life when snakes killed many people, which was true until quite recently in the history of our species. Fears have not caught up to modern life.

Some of the best human qualities, such as cooperation, spirituality, and self-

One fact that evolutionary theory can explain is that human mothers welcome child-

Evolutionary theory in developmental psychology has intriguing explanations for many phenomena: women’s nausea in pregnancy; 1-

All these interpretations are controversial. The influence of nature versus nurture on male/female differences is particularly controversial and provocative (Chapman, 2015). Nonetheless, this theory provides many hypotheses to be explored.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 1.22

1. What is the role of the unconscious in Freud’s theory?

In Freud’s theory, our unconscious drives and motives influence every aspect of our thinking and behavior.

Question 1.23

2. What are the stages envisioned by Freud?

Oral (birth to 1 year); anal (1 to 3 years); phallic (3 to 6 years); latency (6 to 11 years); genital (adolescence); and adulthood

Question 1.24

3. How do Erikson’s stages differ from Freud’s?

Erikson’s stages differ significantly from Freud’s in that they emphasize family and culture, not sexual urges.

Question 1.25

4. How is behaviorism a reaction to psychoanalytic theory?

Behaviorism arose in direct opposition to the psychoanalytic emphasis on unconscious, hidden urges. Behaviorists emphasize nurture, the specific, observable responses from other people and the environment to whatever a developing person does.

Question 1.26

5. How do classical and operant conditioning differ?

In classical conditioning, one stimulus may be associated with another (tone-

Question 1.27

6. How is social learning connected to behaviorism?

The social learning theory is a major extension of behaviorism because it argues that humans are social beings—

Question 1.28

7. What is the basic idea of cognitive theory?

Cognitive theory focuses on changes in how people think over time. According to this theory, thoughts shape attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors.

Question 1.29

8. How does information processing differ from Piaget’s theory?

Unlike Piaget’s stage theory, information processing provides a detailed description of the steps of cognition, with attention to perceptual and neurological processes.

Question 1.30

9. According to Maslow, what are the needs of a person?

Physiological (needing food, water, warmth, and air); safety (feeling protected from injury and death); love and belonging (having loving friends, family, and a community); esteem (being respected by the wider community as well as by oneself); and self-

Question 1.31

10. Why is humanism particularly relevant for the medical professions?

Medical professionals realize that pain can be physical (the first two levels) or social (the next two), and they are aware that their focus on physical health might overlook the person’s higher needs.

Question 1.32

11. How does evolutionary theory apply to human development?

Evolutionary theory contends that to understand human development, one needs to recognize what was adaptive thousands of years ago. Some of the best human qualities, such as cooperation, spirituality, and self-