Developmental Psychopathology

developmental psychopathology

The field that uses insights into typical development to understand and remediate developmental disorders.

Developmental psychopathology links the study of usual development with the study of children with unusual brain or behavior patterns (Cicchetti, 2013b; Hayden & Mash, 2014). Every topic already described, including “genetics, neuroscience, developmental psychology, . . . must be combined to understand how psychopathology develops and can be prevented” (Dodge, 2009, p. 413).

At the outset, four general principles should be emphasized.

Abnormality is normal. Most children sometimes act oddly. At the same time, children with serious disorders are, in many respects, like everyone else.

Disability changes year by year. Most disorders are comorbid, which means that more than one problem is evident in the same person. Which particular disorder is most disabling at a particular time changes, as does the degree of impairment.

Life may get better or worse. Prognosis is difficult. Many children with severe disabilities (e.g., blindness) become productive, happy adults. Conversely, some conditions (e.g., conduct disorder) may become more disabling.

Diagnosis and treatment reflect the social context. Each individual interacts with the surrounding setting—

including family, school, community, and culture— which modify, worsen, or even create psychopathology.

Measuring the Mind

At every age, people with disorders often have unusual brain patterns, which means that understanding the functioning of their brains might help them thrive among people with more typical neurological development. During middle childhood, school learning is crucial. For that reason, we focus first on intellect.

aptitude

The potential to master a specific skill or to learn a certain body of knowledge.

APTITUDE, ACHIEVEMENT, AND IQ In theory, aptitude is the potential to master a specific skill or subject, such as the potential to become an accomplished musician, engineer, or student. Learning aptitude is usually measured by answers to a series of questions. The assumption is that there is one general intelligence, called g (for general). An IQ (intelligence quotient) test consists of questions that, taken together, measure g, thought to be learning potential.

achievement test

A measure of mastery or proficiency in reading, mathematics, writing, science, or some other subject.

In theory, achievement is what has actually been learned, distinct from aptitude. School achievement tests compare scores to norms established for each grade. For example, children of any age who read as well as the average third-

The words in theory precede the definitions of aptitude and achievement above because, although potential and accomplishment are supposed to be distinct, the data find substantial overlap. IQ and achievement scores are strongly correlated.

Flynn effect

The rise in average IQ scores that has occurred over the decades in many nations.

It was once assumed that aptitude was a fixed characteristic, present at birth. Longitudinal data show otherwise. Young children with a low IQ can become above-

Because changes in cohort and education produced intellectual growth in children, IQ tests need to be revised, updated, and renormed to keep the average score at 100—

Psychologists now agree that the brain is like a muscle, affected by mental exercise—

CRITICISMS OF IQ TESTING Since scores change over time, some scientists doubt whether any test can measure the complexities of the human intellect, especially if the test is designed to measure g, general aptitude. According to some experts, children inherit many abilities, some high and some low (e.g., Q. Zhu et al., 2010).

multiple intelligences

The idea that human intelligence is comprised of a varied set of abilities rather than a single, all-

A leading developmentalist, Howard Gardner, contends that humans have multiple intelligences, not just one. Gardner originally described seven intelligences: linguistic, logical-

Although every normal person has some of all nine intelligences, Gardner believes each individual excels in particular ones. For example, someone might be gifted spatially but not linguistically (a visual artist who cannot describe her work) or might have interpersonal but not naturalistic intelligence (an insightful clinical psychologist whose houseplants die).

Gardner’s concepts regarding multiple intelligences influence the curriculum in many primary schools. For instance, children might be allowed to demonstrate their understanding of a historical event via a poster with drawings instead of writing a paper with a bibliography.

Many other scholars (including Robert Sternberg, whose ideas are explained in Chapter 12) find that cultures and families dampen or accelerate particular intelligences. What would happen, for instance, if two children were born with equal creative, musical ability but one child’s parents were musicians and the other child’s parents were tone-

A multi-

But IQ tests also are affected by culture. Some experts try to use culture-

Yet culture may still drag IQ scores down. Perhaps a child is told “never talk to strangers.” That child might not answer the tester’s questions.

Might measuring the brain directly avoid cultural bias? Yes, in theory, but not in practice. Variation is vast in children’s brains: Experts are hesitant to judge intelligence via any brain scan (e.g., Goddings & Giedd, 2014). Furthermore, plasticity makes the results of brain scans, like IQ scores, likely to change.

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

True Grit

Thousands of social scientists—

Many scientists agree that executive control processes with many names (grit, emotional regulation, conscientiousness, resilience, executive function, effortful control) develop over the years of middle childhood and are crucial for cognitive growth. Over the long term, these aspects of character predict achievement in high school, college, and adulthood.

Developmentalists disagree about exactly which qualities are crucial for achievement, with grit considered crucial by some and not others (Ivcevic & Brackett, 2014; Duckworth & Kern, 2011). No one denies that success depends on personality, not just on intellect.

For instance, one of the best longitudinal studies we have (the Dunedin study of an entire cohort of children from New Zealand) found that measures of self-

Among the many influences on children, a pivotal one is having at least one adult who encourages accomplishment. For many children, that adult is their mother, although, especially when parents are neglectful or abusive, a teacher, a religious leader, a coach, or someone else can be the mentor and advocate who helps a child overcome adversity (Masten, 2014).

Why is this an opposing perspective rather than a simple fact? Because grit itself may reflect cultural values that work against low-

The advocates of grit reply that they know that many social forces—

Special Needs in Middle Childhood

Developmental psychopathology is relevant lifelong because “[e]ach period of life, from the prenatal period through senescence, ushers in new biological and psychological challenges, strengths, and vulnerabilities” (Cicchetti, 2013b, p. 458). Turning points, opportunities, and past influences are always apparent.

In middle childhood, the challenge for every child is to learn basic skills. Some children find that mastering academic skills is much more difficult than other children do. Fortunately, most learning problems can be mitigated if treatment is early and properly targeted.

Therein lies the crux of the issue: Although early treatment is best, early and accurate diagnosis is difficult, not only because many disorders are comorbid but also because symptoms differ by age. As you learned in Chapter 4, infants have temperamental differences that might or might not become problems, and in Chapter 6, that aggression and shyness are sometimes normal but sometimes ominous. Difference is not necessarily deficit, but some differences signal that intervention is needed. Which is which?

multifinality

A basic principle of developmental psychopathology which holds that one cause can have many (multiple) final manifestations.

Two basic principles of developmental psychopathology complicate diagnosis and treatment (Hayden & Mash, 2014; Cicchetti, 2013b). First is multifinality, which means that one cause can have many (multiple) final manifestations. For example, an infant who has been flooded with cortisol may become quick to cry or rage or the opposite, unusually placid.

equifinality

A basic principle of developmental psychopathology that holds that one symptom can have many causes.

The second principle is equifinality (equal in final form), which means that one symptom can have many causes. For instance, a nonverbal first-

The complexity of diagnosis is evident in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), often referred to as DSM-

Perhaps. Both multifinality and equifinality make early diagnosis complex: Some children are considered pathological when really they are not, while other children are not diagnosed when early diagnosis and intervention would help. The following three examples are a beginning, because everyone needs to know something about children with special needs. Teachers, counselors, doctors, and nurses need to know much more.

attention-

A condition in which a person not only has great difficulty concentrating for more than a few moments but also is inattentive, impulsive, and overactive.

ATTENTION-

Some impulsive, active, and creative actions are quite normal. However, children with ADHD “are so active and impulsive that they cannot sit still, are constantly fidgeting, talk when they should be listening, interrupt people all the time, can’t stay on task, . . . accidentally injure themselves.” They are “difficult to parent or teach” (Nigg & Barkley, 2014, p. 75).

There is no biological marker for ADHD. Current research, nonetheless, suggests the origin of the disorder is in brain regulation, because of genes, complications of pregnancy, or toxins (such as lead) (Nigg & Barkley, 2014).

Download the DSM-5 Appendix to learn more about the terminology and classification of childhood psychopathology.

ADHD is often comorbid. Explosive rages, later followed by deep regret, are typical for children with many disorders, including ADHD. One surprising comorbidity is deafness: Children with severe hearing loss often are affected in balance and activity, and that seems to make them prone to developing ADHD (Antoine et al., 2013). In this way, ADHD is an example of equifinality; many causes produce one disorder.

U.S. rates of ADHD among children were about 5 percent in 1980. Currently, rates are 7 percent of 4-

Misdiagnosis. If ADHD is diagnosed when another disorder is the problem, treatment might make the problem worse, not better (Miklowitz & Cicchetti, 2010). Many psychoactive drugs alter moods, so a child with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (formerly called childhood-

onset bipolar disorder) might be harmed by drugs that help children with ADHD. Drug abuse. Some adolescents may fake ADHD in order to obtain amphetamines with a doctor’s prescription. Are 15 percent of U.S. teenagers really hyperactive?

Normal behavior considered pathological. In young children, high activity, impulsiveness, and curiosity are normal. If a normal child is diagnosed with ADHD, might that harm the child’s self-

concept? Could normal boy behavior be one reason ADHD is at least twice as common in boys as in girls?

Many adults (71 percent in one study) who were diagnosed with ADHD as children say they no longer have the condition (Barbaresi et al., 2013). Do people overcome or outgrow ADHD, do adults minimize symptoms, or were these adults misdiagnosed? All are possible.

Treatment for ADHD involves: (1) training for the family and child, (2) special education for teachers, and (3) medication. Each of these three is complicated. As equifinality posits, causes vary, so treatment that helps one child may be wrong for another (Mulligan et al., 2013).

specific learning disorder

A marked deficit in a particular area of learning that is not caused by an apparent physical disability, or by an unusually stressful home environment.

Video: Dyslexia: Expert and Children

SPECIFIC LEARNING DISORDER The DSM-

Disabilities in reading, writing, and math undercut academic achievement, destroy self-

dyslexia

Unusual difficulty with reading; thought to be the result of some neurological underdevelopment.

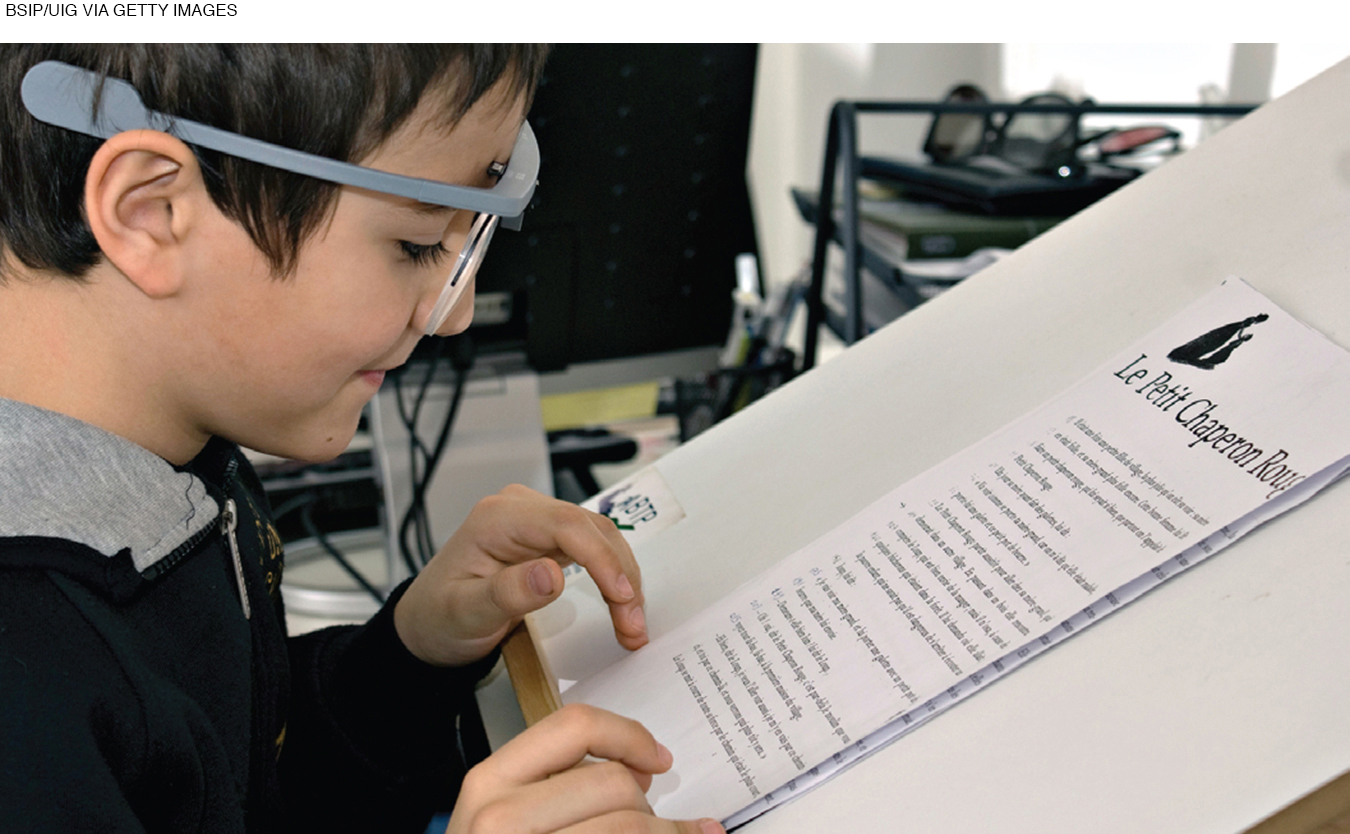

The most common type of specific learning disorder is dyslexia—-unusual difficulty with reading. Dozens of types and causes of dyslexia have been identified, so no single strategy helps every child (O’Brien et al., 2012).

Early theories hypothesized that visual difficulties—

dyscalculia

Unusual difficulty with math, probably originating from a distinct part of the brain.

Another specific learning disorder is dyscalculia—unusual difficulty with math. For example, when asked to estimate the height of a normal room, second-

For specific learning disorders, the problem may originate in the brain, but plasticity allows early remediation to improve brain connections before the young child’s eagerness to learn has been crushed by failure. Almost everyone can learn basic skills if they are given extensive and targeted teaching, encouragement, and practice.

autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

Any of several conditions characterized by inadequate social skills, impaired communication, and unusual play.

AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER Of all the children with special needs, those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are probably the most troubling. Their problems are severe, but both causes and treatments are hotly disputed. As a result, as Thomas Insel, director of the National Institute of Mental Health says, parents and advocates of children with autism spectrum disorder are “the most polarized, fragmented community” (quoted in Solomon, 2012, p. 280).

Video: Current Research into Autism Spectrum Disorder explores why the causes of ASD are still largely unknown.

Many children with ASD show symptoms in the first year of life, but some seem normal and then suddenly regress at about age 2 or 3, perhaps because a certain level of brain development, or a particular medical insult, occurs (Klinger et al., 2014). Most are diagnosed at age 4 or later (MMWR, March 28, 2014), although earlier intervention is best.

Autism spectrum disorder has three characteristics: (1) poor social understanding, (2) impaired language, and (3) unusual play patterns, such as fascination with trains, lights, or spinning objects. In the past, children who developed slowly were usually diagnosed as having a “pervasive developmental disorder” or as “mentally retarded.” (The term “mental retardation,” used in DSM-

Much has changed. Far more children are diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, and far fewer with intellectual disability. In the United States, among 8-

The DSM-

Often children with autism spectrum disorder have a hypersensitive sensory cortex: They are unusually upset by noise, light, and other sensations. Hundreds of genes and dozens of brain abnormalities are more common in people with ASD than in the general population.

Why are far more children diagnosed with ASD in 2015 than in 1990? Has the incidence really increased or are children diagnosed who would not have been earlier (Klinger et al., 2014). Children who once were diagnosed with Asperger syndrome are now said to have “autism spectrum disorder without language or intellectual impairment” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, p. 32). Is that more accurate?

neurodiversity

The idea that people have diverse brain structures, with each person having neurological strengths and weaknesses that should be appreciated, in much the same way diverse cultures and ethnicities are welcomed.

As more is understood, many people wonder whether ASD is a disorder needing cure or an indication that parents and society foolishly expect everyone to be fluent talkers, gregarious, and flexible—

Equifinality certainly applies to ASD: A child can have symptoms for many reasons; no single gene causes the disorder. That makes treatment difficult; an intervention that helps one child is worthless for another.

It is known that biology is crucial (genes, copy number abnormalities, birth complications, prenatal injury, perhaps chemicals during fetal or infant development) and that family nurture does not cause ASD but may modify it. Social and language engagement of the child early in life seems the most promising treatment.

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Drug Treatment for Children

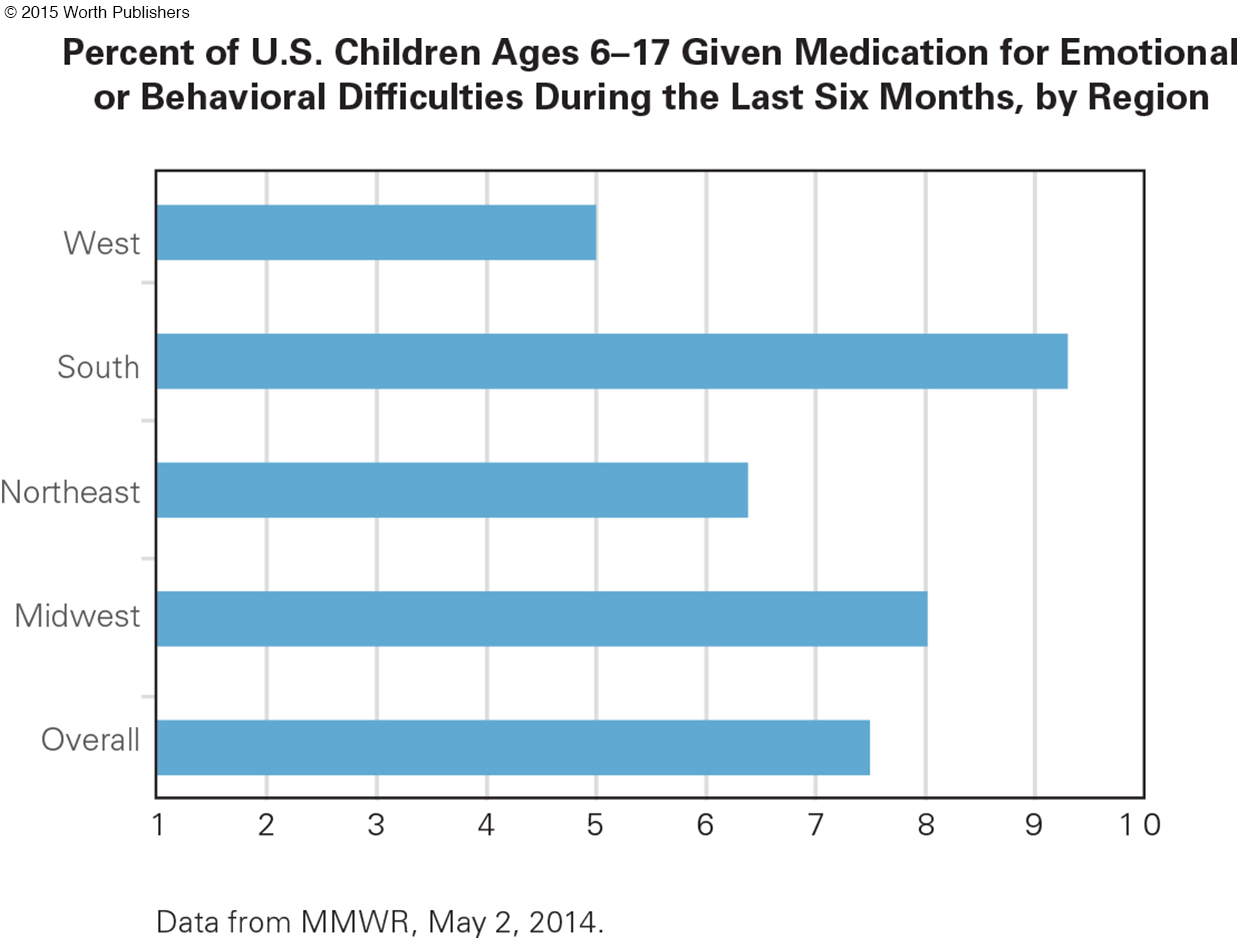

In the United States, more than 2 million people younger than 18 take prescription drugs to regulate their emotions and behavior (see Figure 7.6). The rates are about 14 percent for teenagers (Merikangas et al., 2013), about 10 percent for 6-

Drug treatment for children poses a dilemma. Many adults are upset by normal child behavior. Since any physician can prescribe a drug to quiet a child, thousands of children may be overmedicated. But because many parents are suspicious of drugs, refusing to believe that their child needs help (Moldavsky & Sayal, 2013; Rose, 2008), thousands of children may suffer without the drugs they need to learn, make friends, and so on.

Sometimes drugs are helpful, although not a cure. In one careful study, when children with ADHD were given appropriate medication, carefully calibrated, they were more able to concentrate. However, eight years later, many children on and off medication still had learning difficulties (Molina et al., 2009). Many other studies also find that children with ADHD are likely to have academic and vocational difficulties lifelong (Molina et al., 2013).

THINK CRITICALLY: What are several possible explanations for the ethnic differences in use of ADHD medication?

Ethnic differences are found in parent responses, teacher responses, and treatment for children. In the United States, it seems that when children are diagnosed with ADHD, African American and Hispanic parents are less likely that European American parents to give them medication (Morgan et al., 2013). Why?

Drugs are also controversial for adults. Medication seems to help adolescents and adults with ADHD (Surman et al., 2013), but most psychologists believe that drugs should never be the first, or the only, treatment for any disorder. In China, psychoactive medication is rarely used. A Chinese child with ADHD symptoms is thought to need correction, not medication (Yang et al., 2013). Wise or cruel?

International comparisons raise many questions. For instance, one study asked 158 child psychologists—

Parents say Lynda has been hyperactive, with poor boundaries and disinhibited behavior since she was a toddler. . . Lynda has taken several stimulants since age 8. She is behind in her school work, but IQ normal. . . . Psychological testing, age 8, described frequent impulsivity, tendencies to discuss topics unrelated to tasks she was completing, intermittent expression of anger and anxiety, significantly elevated levels of physical activity, difficulties sitting still, and touching everything. Over the past year Lynda has become very angry, irritable, destructive and capricious. She is provocative and can be cruel to pets and small children. She has been sexually inappropriate with peers and families, including expressing interest in lewd material on the Internet, Play Girl magazine, hugging and kissing peers. She appears to be grandiose, telling her family that she will be attending medical school, or will become a record producer, a professional wrestler, or an acrobat. Throughout this period there have been substantial marital difficulties between the parents.

[Dubicka et al., 2008, appendix p. 3]

Most (81 percent) of the clinicians diagnosing Lynda thought she had ADHD, and most thought she had another disorder as well. The Americans were likely to suggest a second and third disorder, with 75 percent of them specifying bipolar disorder (now called disruptive mood dysregulation disorder). Only 33 percent of the British psychologists said bipolar (Dubicka et al., 2008).

Lynda’s parents thought she had ADHD since toddlerhood; a pediatrician agreed, and at age 8 put her on drugs. Now, at age 11, she seemed to be getting worse, not better, while her parents were increasingly hostile to each other.

Unfortunately, when psychopathology is evident, parental responses vary from irrational hope to deep despair, from blaming doctors and chemical additives to feeling guilty for what they did wrong. Many parents sue schools, or doctors, or the government; many subject their children to drugs and other biological “cures.”

Andrew Solomon (2012) writes about one child with autism, medicated with

Abilify, Topamax, Seroquel, Prozac, Ativan, Depakote, trazodone, Risperdal, Anafranil, Lamictal, Benadryl, melatonin, and the homeopathic remedy, Calms Forté. Every time I saw her, the meds were being adjusted again . . . . [he also describes] physical interventions—

[pp. 229, 270]

For every problem, from ADHD to specific learning disorder to autism spectrum disorder, developmentalists believe that family interactions and school context are crucial, even though the easiest intervention is to prescribe drugs. Parents are not the cause of child psychopathology, but they may be crucial for treatment.

Special Education

The overlap of the biosocial, cognitive, and psychosocial domains means that parents, teachers, therapists, and researchers need to work together to help each child. However, deciding whether or not a child should receive special education, and what that education should be, is complex. Parents and educators often disagree.

LABELS, LAWS, AND LEARNING In the United States, recognition that the distinction between normal and abnormal is not clear-

Consequently, children with special needs usually learn in regular classes. Sometimes a class is an inclusion class, which means that children with special needs are “included” in the general classroom, with “appropriate aids and services” (ideally from a trained teacher who works with the regular teacher).

response to intervention (RTI)

An educational strategy that uses early intervention to help children who demonstrate below-

A more recent educational strategy is called response to intervention (RTI) (Fletcher & Vaughn, 2009; Shapiro et al., 2011; Ikeda, 2012). All children are taught specific skills—

individual education plan (IEP)

A document that specifies educational goals and plans for a child with special needs.

Only when repeated, focused intervention does not work are children referred for testing and observation to understand why they did not respond to the extra help. Then the school may propose an individual education plan (IEP), which is supposed to remedy the problem.

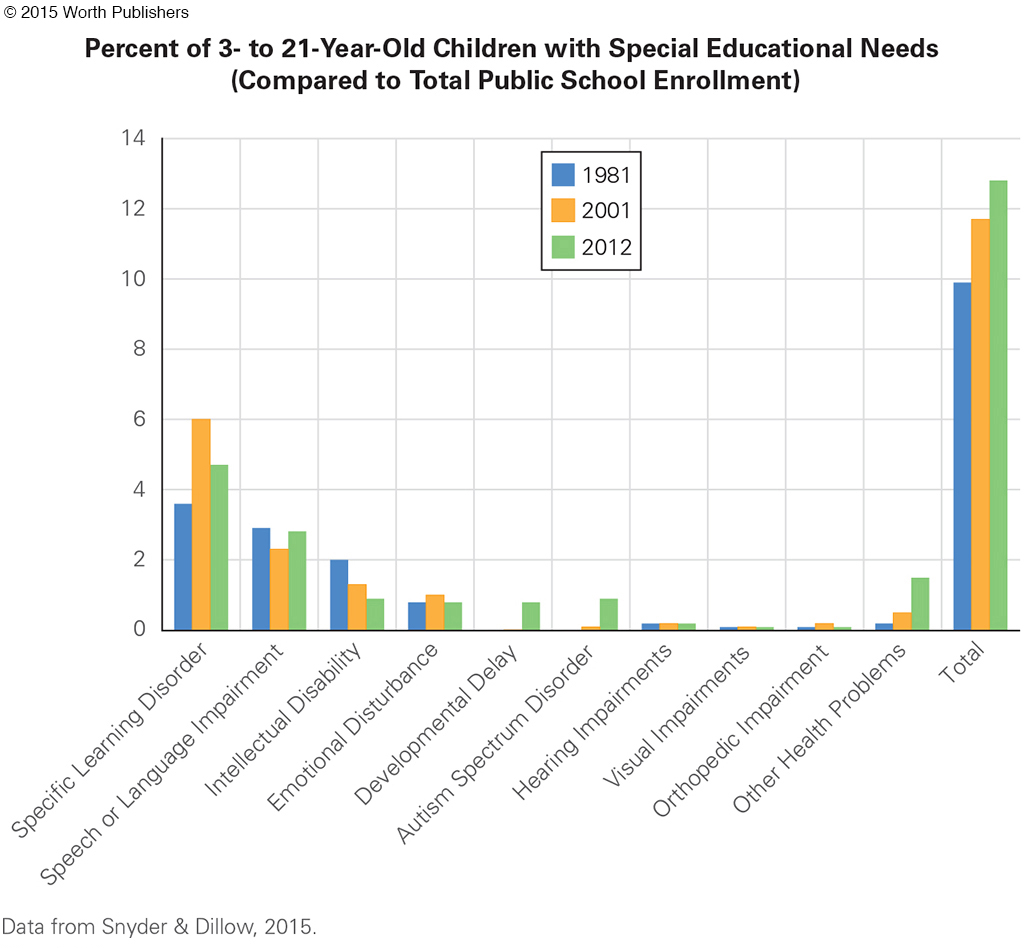

Unfortunately, much is unknown about which remediation is best. The special needs that attract most research are not the more common ones (see Figure 7.7). One example: In the United States, “research funding in 2008–

Internationally, the connection between special needs and education varies, for cultural and historical reasons more than child-

GIFTED AND TALENTED Children who are unusually gifted may have special educational needs, but they are not covered by federal laws in the United States. Instead, each U.S. state selects and educates gifted and talented children in a particular way. Educators, political leaders, scientists, and everyone else argue about who is gifted and what should be done about them.

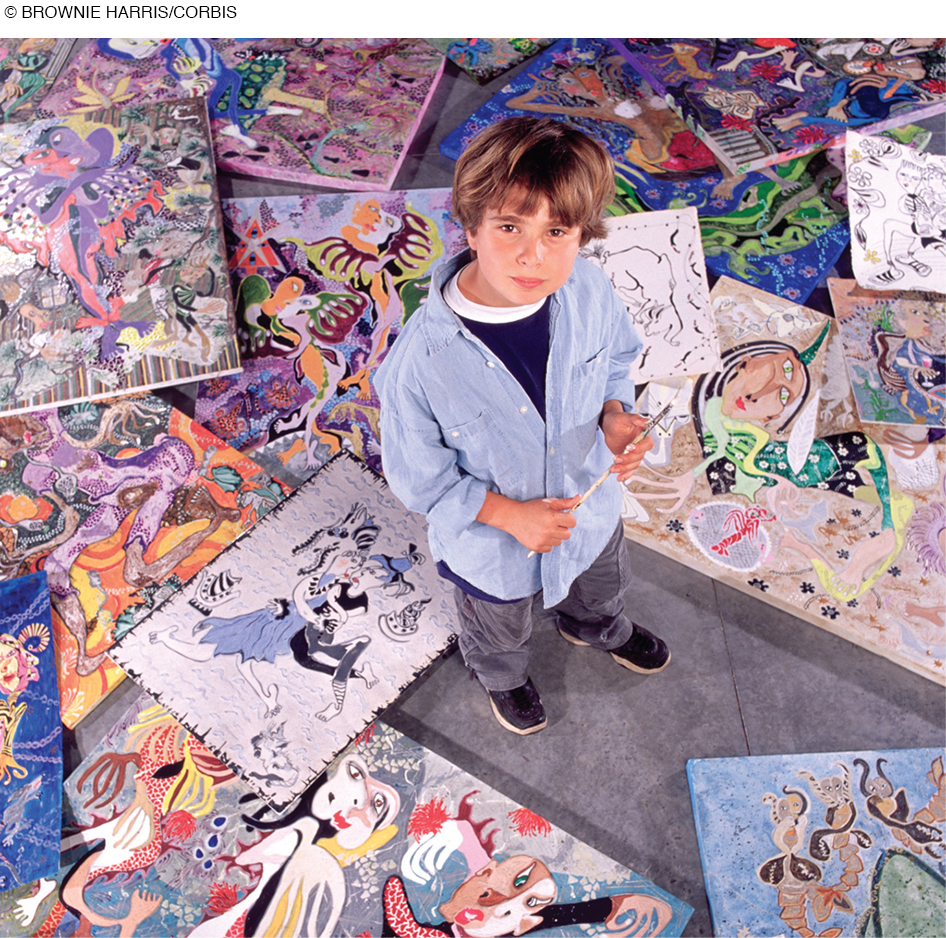

A hundred years ago, the definition was simple: high IQ. A famous longitudinal study followed a thousand “genius” children (Terman, 1925). Even today, some school systems define “gifted” as having an IQ of 130 or above (attained by 1 child in 50). Other children are unusually talented, perhaps recognized by their parents at a young age but not usually by their teachers. Mozart composed music at age 3; Pablo Picasso created works of art at age 4.

A hundred years ago, school placement was simple, too: The gifted were taught with children who were their mental age, not their chronological age. Today that is rarely done because many such children missed social skills and friendship. One woman remembers:

Nine-

[Rachel, quoted in Freeman, 2010, p. 27]

Calling herself a weed suggests that she never overcame her conviction that she was less cherished than the other children.

Historically, many famous musicians, artists, and scientists were child prodigies whose fathers recognized their talent (often because the father was talented) and taught them. Often they did not attend regular school. Mozart’s father transcribed his earliest pieces and toured Europe with his gifted son. Picasso’s father removed him from school in second grade so he could create all day.

That solution also had pitfalls. Although intense early education at home nourishes talent, neither Mozart nor Picasso had happy adult lives or learned basic skills. Picasso said he never learned to read or write, and Mozart had a poor understanding of math and money. Similar problems are evident in gifted young singers, film stars, and athletes.

Neuroscience has recently discovered that children who develop their musical talents with extensive practice in early childhood grow specialized brain structures, as do child athletes and mathematicians. Since plasticity means that children learn whatever their context teaches, special talents may be enhanced with special education, an argument for elementary school classes that are designated for gifted and talented children where their talents can develop while they learn basic social and academic skills.

A related kind of child is the one who is unusually creative (Sternberg et al., 2011). The child may be a divergent thinker, finding many solutions and questions for every problem. Such children joke in class, resist drudgery, ignore homework, and bedevil their teachers. They may become innovators, inventors, and creative forces.

They refuse to be convergent thinkers, who choose the correct answer on school exams. One divergent thinker was Charles Darwin, whose “school reports complained unendingly that he wasn’t interested in studying, only shooting, riding, and beetle-

THINK CRITICALLY: If you were the parent of a gifted child, what would you have your child forgo to develop his or her talent?

As you can see, all three types of children—

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 7.32

1. How do aptitude and achievement differ in theory and practice?

In theory, aptitude is the potential to master a specific skill or subject, such as the potential to become an accomplished musician, engineer, or student. Learning aptitude is usually measured by answers to a series of questions (such as on an IQ test). In theory, achievement is what has actually been learned, distinct from aptitude. School achievement tests compare scores to norms established for each grade.

Question 7.33

2. Why might teachers need to know the theory of multiple intelligences?

Teachers need to be able to recognize their students’ strengths and weaknesses. For example, a student who is gifted spatially but not linguistically may be allowed to demonstrate his understanding of a historical event via a poster with drawings instead of writing a paper with footnotes.

Question 7.34

3. How might a child’s culture affect the results of an IQ test?

Culture may drag IQ scores down. Perhaps a child is told “never talk to strangers.” That child might not answer the tester’s questions. Some experts try to use culture-

Question 7.35

4. Why might a child with ADHD have difficulty learning?

Children with ADHD are so active and impulsive that they cannot sit still, are constantly fidgeting, talk when they should be listening, interrupt people all the time, and can’t stay on task.

Question 7.36

5. How should specific learning disorders be recognized and remedied?

Children with specific learning disorders have difficulty mastering skills that most children acquire easily. For specific learning disorders, the problem may originate in the brain, but plasticity allows early remediation to improve brain connections before the young child’s eagerness to learn has been crushed by failure. Almost everyone can learn basic skills if they are given extensive and targeted teaching, encouragement, and practice.

Question 7.37

6. What are three signs of autism spectrum disorder?

Autism spectrum disorder has three characteristics: (1) poor social understanding; (2) impaired language; and (3) unusual play patterns, such as fascination with trains, lights, or spinning objects.

Question 7.38

7. How and when should children with special needs have special education?

According to the 1975 Education of All Handicapped Children Act, children with special needs must be educated in the “least restrictive environment.” The law has been revised, but the goal remains that children with special needs should not be segregated unless efforts to remediate problems within the regular classroom have failed.

Question 7.39

8. Why might gifted children benefit, or be harmed, by special education?

All three types of gifted children—

Question 7.40

9. When is it better for children with special needs to be in a regular class?

Children with special needs usually learn in regular classes. Sometimes a class is an inclusion class, which means that children with special needs are included in the general classroom, with appropriate aids and services.