Theories of Infant Psychosocial Development

Theories of Infant Psychosocial Development

Consider again the theories discussed in Chapter 2. As you will see, theories lead to insight and applications that are relevant for the final topic of this chapter, infant day care.

Psychoanalytic Theory

Psychoanalytic theory connects biosocial and psychosocial development. Sigmund Freud and Erik Erikson each described two distinct stages of early development, one in the first year and one beginning in the second.

Freud: Oral and Anal Stages

According to Freud (1935, 1940/1964) the first year of life is the oral stage, so named because the mouth is the young infant’s primary source of gratification. In the second year, with the anal stage, pleasure comes from the anus—

Freud believed that the oral and anal stages are fraught with potential conflicts. If a mother frustrates her infant’s urge to suck—

Especially for Nursing Mothers You have heard that if you wean your child too early he or she will overeat or become an alcoholic. Is it true?

Response for Nursing Mothers: Freud thought so, but there is no experimental evidence that weaning, even when ill-

Similarly, if toilet training is overly strict or if it begins before the infant is mature enough, then the toddler’s refusal—

Erikson: Trust and Autonomy

trust versus mistrust Erikson’s first crisis of psychosocial development. Infants learn basic trust if the world is a secure place where their basic needs (for food, comfort, attention, and so on) are met.

According to Erikson, the first crisis of life is trust versus mistrust, when infants learn whether or not the world can be trusted to satisfy basic needs. Babies feel secure when food and comfort are provided with “consistency, continuity, and sameness of experience” (Erikson, 1963, p. 247). If social interaction inspires trust, the child (later the adult) confidently explores the social world.

autonomy versus shame and doubt Erikson’s second crisis of psychosocial development. Toddlers either succeed or fail in gaining a sense of self-

The second crisis is autonomy versus shame and doubt, beginning at about 18 months, when self-

Erikson was aware of cultural variations. He knew that mistrust and shame could be destructive or not, depending on local norms and expectations. Westerners expect toddlers to go through the stubborn and defiant “terrible twos”; that is a sign of the urge for autonomy. Parents elsewhere expect toddlers to be docile and obedient, and “shame is a normative emotion that develops as parents use explicit shaming techniques” to encourage children’s loyalty and harmony within their families (Mascolo et al., 2003, p. 402).

Behaviorism

From the perspective of behaviorism, emotions and personality are molded as parents reinforce or punish a child. Behaviorists believe that parents who respond joyously to every glimmer of a grin will have children with a sunny disposition. The opposite is also true:

Failure to bring up a happy child, a well-

[Watson, 1928, pp. 7, 45]

social learning The acquisition of behavior patterns by observing the behavior of others.

Later behaviorists recognized that infants’ behavior also has an element of social learning, as infants learn from other people. Albert Bandura conducted a famous experiment (Bandura, 1977) in which young children were frustrated by being told they could not play with some attractive toys. They were then left alone with a mallet and a rubber clown (Bobo) after seeing an adult hit Bobo. Both boys and girls pounded and kicked Bobo as the adult had done, indicating that they had learned from observation.

Since that experiment, developmentalists have demonstrated that social learning occurs throughout life (Morris et al., 2007; Rendell et al., 2011). Toddlers express emotions in various ways—

For example, a boy might develop a hot temper if his father’s outbursts seem to win his mother’s respect; a girl might be coy, or passive-

Parents often unwittingly encourage certain traits in their children. This is evident in the effects of proximal versus distal parenting, explained below.

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Proximal and Distal Parenting

Should parents carry infants most of the time, or will that spoil them? Should babies have many toys, or will that make them too materialistic?

proximal parenting Caregiving practices that involve being physically close to the baby, with frequent holding and touching.

distal parenting Caregiving practices that involve remaining distant from the baby, providing toys, food, and face-

Answers to these questions refer to the distinction between proximal parenting (being physically close to a baby, often holding and touching) and distal parenting (keeping some distance—

The research finds notable variation in parenting approach (Keller et al., 2010). For example, in a longitudinal study (H. Keller et al., 2004) comparing child-

Especially for Statisticians Note the sizes of the samples: 78 mother–

Response for Statisticians: Probably not. These studies are reported here because the results were dramatic (see Table 73) and because the two studies pointed in the same direction. Nevertheless, replication by other researchers is needed.

| Cameroon | Athens, Greece | |

|---|---|---|

| I. Infant- |

||

| Percent of time held by mother | 100% | 31% |

| Percent of time playing with objects | 3% | 40% |

| II. Toddler behavior at 18 months | ||

| Self- |

3% | 68% |

| Immediate compliance with request | 72% | 2% |

| Source: Adapted from Keller et al., 2004. | ||

The researchers hypothesized that proximal parenting would result in toddlers who were less self-

Especially for Pediatricians A mother complains that her toddler refuses to stay in the car seat, spits out disliked foods, and almost never does what she says. How should you respond?

Response for Pediatricians: Consider the origins of the misbehavior—

The predictions were accurate. At 18 months, these same infants were tested on self-

The researchers then reanalyzed all their data, child by child. They found that, even apart from culture, proximal or distal play at 3 months was highly predictive: Greek mothers who, unlike most of their peers, were proximal parents had more obedient toddlers. Further research in other nations confirmed these conclusions (Borke et al., 2007; Kärtner et al., 2011).

Cultural attitudes shape every aspect of infant care. Is independence valued over dependence? Is autonomy more important than compliance? Cultures differ because values differ. If toddlers are asked to put away toys that they did not use (a task measuring compliance), and they do so without protest, is that wonderful or disturbing?

Should you pick up your crying baby (proximal) or give her a pacifier (distal)? Should you breast-

Cognitive Theory

Cognitive theory holds that ideas, concepts and assumptions determine a person’s perspective. Early experiences are important because beliefs, perceptions, and memories make them so, not because they are buried in the unconscious (psychoanalytic theory) or burned into the brain’s patterns (behaviorism).

working model In cognitive theory, a set of assumptions that the individual uses to organize perceptions and experiences. For example, a person might assume that other people are trustworthy and be surprised by an incident in which this working model of human behavior is erroneous.

According to many cognitive theorists, early experiences help infants develop a working model, which is a set of assumptions that become a frame of reference for later life (Johnson et al., 2010). It is a “model” because early relationships form a prototype, or blueprint; it is “working” because, although it is used, it is not necessarily fixed or final.

Ideally, infants develop “a working model of the self as valued, loved, and competent” and “a working model of parents as emotionally available, loving, sensitive and supportive” (Harter, 2006, p. 519). However, reality does not always conform to this ideal. A 1-

The crucial idea, according to cognitive theory, is that an infant’s early experiences themselves are not necessarily pivotal, but the interpretation of those experiences is (Olson & Dweck, 2009). Children may misinterpret their experiences, or parents may offer inaccurate explanations, and these form ideas that affect later thinking and behavior.

In this way, working models formed in childhood echo lifelong. A hopeful message from cognitive theory is that people can rethink and reorganize their thoughts, developing new models. Our mistrustful girl might marry a faithful and loving man and gradually develop a new working model.

Humanism

Remember from Chapter 2 that Maslow described a hierarchy of needs (physiological, safety/security, love/belonging, success/esteem, and self-

Humanism reminds us that caregivers also have needs and that their needs influence how they respond to infants. Self-

For example, while all experts endorse breast-

For example, one mother of a 1-

My son couldn’t latch so I was pumping and my breasts were massive and I’m a pretty small woman with big breasts and they were enormous during pregnancy. It has always been a sore spot for me and I’ve never loved my breasts. And that has been hard for me in not feeling good about myself. And I stopped pumping in January and slowly they are going back and I’m beginning to feel some confidence again and that definitely helps. Because I felt overweight, your boobs are not your own and you are exhausted and your body is strange it’s just really hard to want to share that with someone. They think you are beautiful, they love it and love you the way you are but it is not necessarily what you feel.

[quoted in Shapiro, 2011, p. 18]

This woman’s need for self-

Her personal needs may have been unmet since puberty (she says, “I’ve never loved my breasts”). She blames her husband for not understanding her feelings and her son who “couldn’t latch.” Since all babies learn to latch with time and help, this woman’s saying that her son couldn’t latch suggests something amiss in synchrony and attachment—

By contrast, some parents understand their baby’s need for safety and security (level 2) even if they themselves are far beyond that stage. Kevin is an example.

Kevin is a very active, outgoing person who loves to try new things. Today he takes his 11-

[Lerner & Dombro, 2004, p. 42]

Evolutionary Theory

Remember that evolutionary theory stresses two needs: survival and reproduction. Human brains are extraordinarily adept at those tasks. However, it takes about 20 years of maturation before the human brain is fully functioning. A child must be nourished, protected, and taught by adults much longer than offspring of any other species. Infant and parent emotions ensure this lengthy protection (Hrdy, 2009).

Emotions for Survival

Infant emotions are part of the evolutionary mandate. All the reactions described in the first part of this chapter—

For example, newborns are extraordinarily dependent, unable to walk or talk or even sit up and feed themselves for months after birth. They must attract adult devotion—

Adults call their hairless, chinless, round-

If humans were motivated merely by financial reward, no one would have children. Yet evolution has created adults who find parenting worth every sacrifice. The costs are substantial: food (even breast milk requires the mother to eat more), diapers, clothes, furniture, medical bills, toys, and child care (whether paid or unpaid) are just a start. Before a child becomes independent, many parents have paid for a bigger home, for education, for vacations, and much more. These are just the financial costs; the emotional costs are even greater.

Reproductive nurturance depends on years of self-

Evolutionary theory holds that, over human history, attachment, with proximity-

As explained in Chapter 4, human bonding is unlike that of goats and sheep—

Allocare

allocare The care of children by people other than their biological parents.

Evolutionary social scientists note that if mothers were the exclusive caregivers of each child until children were adults, a given woman could rear only one or two offspring—

Compared with many other species, human mothers have evolved to let other people help with child care, and other people are usually eager to do so (Kachel et al., 2011). Throughout the centuries, the particular person to provide allocare has varied by culture and ecological conditions.

Often fathers helped but not always: Some men were far away, fighting, hunting, or seeking work; some had several wives and a dozen or more children. In those situations, other women (daughters, grandmothers, sisters, friends) and sometimes other men provided allocare (Hrdy, 2009).

Infant Day Care

TOM SALYER/STOCK CONNECTION WORLDWIDE/NEWSCOM

Cultural variations in allocare are vast, and each theory just described can be used to justify or criticize certain variations. This makes infant day care a controversial topic. No theory directly endorses any particular position. Nonetheless, theories are made to be useful, so we will include some discussion about the day-

It is estimated that about 134 million babies will be born each year from 2010 to 2021 (United Nations, 2013). Most newborns will be cared for primarily or exclusively by their mothers, and then allocare will increase as the baby gets older. Fathers and grandmothers are usually the first nonmaternal caregivers; only about 15 percent of infants (birth to age 2) receive daily care from a nonrelative who is paid and trained to provide it.

Statistics on the precise incidence and consequences of various forms of infant care in each nation are difficult to find or interpret because “informal in-

Many people believe that the practices of their own family or culture are best and that other patterns harm either the infant or the mother. This is another example of the difference-

International Comparisons

Center-

High-

|

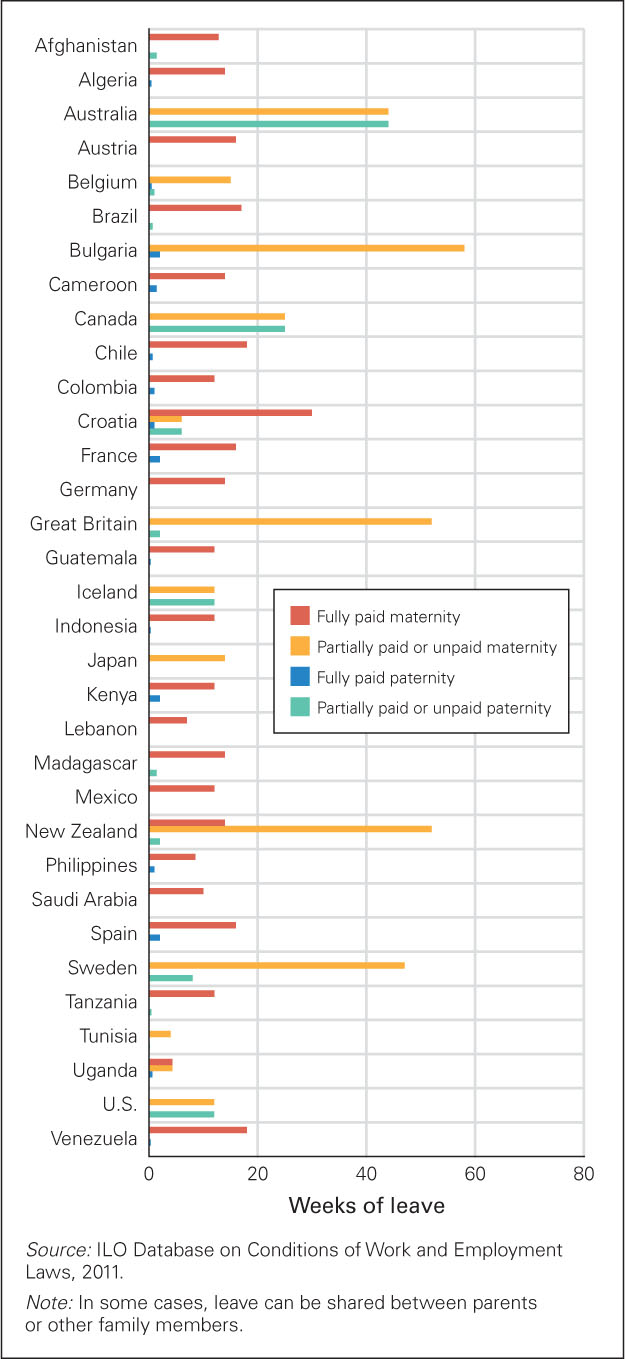

Involvement of relatives also varies. Worldwide, fathers increasingly take part in baby care. Most nations provide some paid leave for mothers; some also provide paid leave for fathers; and several nations provide paid family leave that can be taken by either parent or shared between them. The length of paid leave varies from a few days to about 15 months (see Figure 7.3).

FIGURE 7.3

A Changing World No one was offered maternity leave a century ago because the only jobs that mothers had were unregulated ones. Now, virtually every nation has a maternity leave policy, revised every decade or so. As of 2012 only Australia, Iceland, and Canada offered policies reflecting gender equality. That may be the next innovation in many nations.Note: In some cases, leave can be shared between parents or other family members.

When all the developed nations are considered, the United States is one of the few without paid leave. Note, however, practices do not necessarily align with policies. In many nations, parents have unregulated employment and take off only a day or two for birth, although national policy is more generous. The reverse is also true: some fathers and mothers hesitate to take allowed parental leave, because it may undercut their advancement.

Underlying every national policy and private practices are theories about what is best for infants. When nations mandate paid leave, the belief is that infants need maternal care and that employers should encourage such care to occur.

In the United States, marked variations are apparent by state and by employer, with some employers far more generous than the law requires. Federal policy mandates that a job be held for a parent who takes unpaid leave of up to 12 weeks unless the company has fewer than 50 employees. Almost no company pays for paternal leave, with one exception: The U.S. military allows 10 days of paid leave for fathers.

Observation Quiz What three cultural differences do you see in the pictures to the left?

Answer to Observation Quiz: The Bangladeshi children are dressed alike, are the same age, and are all seated around toy balls in a net—

© DOLI AKTER/AGE FOTOSTOCK

In the United States, only 20 percent of infants are cared for exclusively by their mothers (i.e., no other relatives or babysitters are involved in baby care) throughout their first year. This is in contrast to Canada, which is similar to the United States in ethnic diversity but has lower rates of maternal employment: in the first year of life, 60 percent of Canadians are cared for only by their mothers (Babchishin, et al., 2013). Obviously, these differences are affected by culture more than by the universal psychosocial needs of babies and parents. Changes occur through economic and political pressures—

One might hope that centuries of maternal care, paternal care, and allocare would provide clear conclusions about the best practices. Unfortunately, the evidence is mixed. In most nations and centuries, infants were more likely to survive if their grandmothers were nearby, especially during the time immediately after weaning (Sear & Mace, 2008). This is thought to have been because the grandmothers provided essential nourishment and protection.

However, in at least one community (northern Germany, 1720–

Evidence on the effects of early nonmaternal care suggests that national policies, cultural expectations, and family income are at least as significant as the actual hours in care and who provides it (Côté et al., 2013; Solheim et al., 2013).

No matter what form of care is chosen or what theory is endorsed, responsive, individualized care with stable caregivers seems best (Morrissey, 2009). Caregiver change is especially problematic for infants because each simple gesture or sound that a baby makes not only merits an encouraging response but also requires interpretation by someone who knows that particular baby well.

For example, “baba” could mean bottle, baby, blanket, banana, or some other word that does not even begin with b. This example is an easy one, but similar communication efforts—

Some babies seem far more affected than others by the quality of their care (Phillips et al., 2011; Pluess & Belsky, 2009). In fact, if the home environment is poor—

As one review explained: “This evidence now indicates that early nonparental care environments sometimes pose risks to young children and sometimes confer benefits” (Phillips et al., 2011). Differential sensitivity is evident: For genetic and familial reasons, the choice about how best to provide care for an infant varies from case to case.

Maternal Employment in Infancy

Especially for Day-

Response for Day-

Closely tied to the issue of infant day care is the issue of maternal employment. Until recent history it was assumed that mothers should stay home with their children. That is the recommendation of both psychoanalytic and behaviorist theory. That assumption has been challenged, partly by the idea that mothers have needs that merit attention (humanism) and by historical evidence that allocare was typical over the centuries (evolutionary theory).

A summary of the longitudinal outcomes of nonmaternal infant care finds “externalizing behavior is predicted from a constellation of variables in multiple contexts…and no study has found that children of employed mothers develop serious emotional or other problems solely because their mothers are working outside the home” (McCartney et al., 2010, pp. 1, 16).

Indeed, research from the United States indicates that children generally benefit if their mothers are employed (Goldberg et al., 2008). The most likely reasons are that maternal income reduces parental depression and increases family wealth, both of which correlate with happier and more successful children.

That is a comforting conclusion for employed mothers, but again, other interpretations are possible. It may be that the women who were able to find worthwhile work were also more capable of providing good infant care than women who were unemployed.

Marital relationships benefit from shared activities, so couples who rarely spend time together are likely to be less dedicated to each other. Sharing child care—

As you see, every study reflects many variables, just as every theory has a different perspective on infant care. Given that, and given divergent cultural assumptions, it is not surprising that researchers find mixed evidence on infant care and caregivers. Many factors are relevant: infant gender and temperament, family income and education, and especially the quality of care at home and elsewhere.

Thus, as is true of many topics in child development, questions remain. But one fact is without question: Each infant needs personal responsiveness—

SUMMING UP

All theories recognize that infant care is crucial: Psychosocial development depends on it. Psychoanalytic theory stresses early caregiving routines, developing oral or anal characteristics according to Freud and trust and autonomy according to Erikson. Behaviorists emphasize early learning, with parents’ reinforcing or punishing infant reactions. Cognitive theories emphasize working models. In all these theories, lifelong patterns are said to begin in infancy, but later change is possible. Culture is crucial.

Humanists consider the basic needs of adults as well as infants. Consequently, they acknowledge the parental side of the parent–

The psychosocial impact of infant day care depends on many factors, including the culture. Although many nations pay mothers of infants to stay home with their babies, maternal employment does not seem harmful if someone else provides responsive care. Continuity is crucial; mothers, fathers, and others can all be good caregivers.