1.3 Psychology’s History

Thus far in this chapter, we have focused on the present: today’s psychological science. Now let’s look back in time. Understanding psychology’s past can enrich your understanding of the contemporary science.

When reviewing psychology’s history, it is hard to know where to start. Humans have been asking psychological questions about humans—

Psychologists in the Ancient World: Aristotle and the Buddha

Preview Question

How were Aristotle and the Buddha like and not like modern psychologists?

How were Aristotle and the Buddha like and not like modern psychologists?

The first systematic psychological theories are ancient. Psychology’s history began more than 2400 years ago.

ARISTOTLE. Many foundations of Western civilization were established in a relatively short period of time by the people of a relatively small city—

The Athenians also explored psyche—in Greek, “the soul or mind.” Athens’s greatest “psyche-

Aristotle was not a psychologist in the contemporary sense of the word. He didn’t answer questions by using scientific methods—

Aristotle was interested in classification. To classify something is to identify it as a member of a category. For instance, if Fido strolls by and you call him a “dog,” you’ve classified him, placing him into the category “dog.” Aristotle classified different types of mental capacities, that is, the variety of things that the human mind is able to do. Remarkably, his ancient classification scheme seems modern; it resembles classifications found in twenty-

Perception: The ability of people and animals to become aware of objects in the environment.

Memory: Aristotle not only classified memory as a distinct ability, but also recognized variations among different types of memory. Some memories, he noted, “pop” into mind (e.g., while reading this, you might suddenly think of something a friend said recently), whereas others come to mind only with effort (e.g., during an exam, it might take effort to remember the name of the ancient Greek who classified different mental abilities).

Desire, rational thought, and action: Aristotle discussed differences between humans and animals. Both, he said, have desires that motivate behavior. But unlike animals, humans also have rational thought, that is, careful, logical thinking. Human action, then, has two distinct causes that frequently conflict: desire and rational thinking.

We’ll say more about Aristotle in a moment. But first, let’s look at the ideas of someone who lived at about the same time as Aristotle, but in a different part of the world.

When was the last time rational thinking conflicted with desire in determining your behavior?

THE BUDDHA. In northern India, in the sixth to fifth century bce, the son of a wealthy ruler decided to seek wisdom rather than wealth. History tells us that he found it. He became known as the Buddha.

You may think of the Buddha as a religious figure, which certainly is correct. Yet he posed questions that were purely psychological. In particular, he asked about the causes of emotion: Why, despite their intelligence, are people so prone to experiencing negative emotions—

Do you think the Buddha was correct in his belief concerning the cause of suffering?

The Buddha suggested a cure for suffering; in contemporary psychological language, he proposed a “therapy” to reduce negative emotion. It was meditation. Meditating on the nature of self and the causes of suffering, he said, could bring insight that eliminates emotional distress.

Like Aristotle, the Buddha did not employ scientific methods; he was not a psychologist in the contemporary sense of the term. Yet his ideas seem contemporary. Researchers today, like the Buddha, study how thinking processes create emotional distress (Chapters 10 and 14). They also explore the effects of meditation on brain functioning (Chapter 9).

LEARNING FROM THE ANCIENTS. Our look at Aristotle and the Buddha teaches us two lessons. The first concerns the question of what is, and is not, “new” in contemporary psychological science.

Although many questions asked in contemporary psychology are new, what is striking is that so many have been asked for ages. Ancient questions—

The second lesson concerns the goals of psychology, that is, the aims of all this thinking about people, the mind, and the brain. Aristotle’s and the Buddha’s goals differed. Aristotle pursued knowledge for knowledge’s sake: “He wished to understand men for the sake of that understanding” (Watson, 1963, p. 44). The Buddha pursued a practical goal: He was “not motivated by theoretical curiosity” but by “the overriding practical aim … of deliverance from suffering” (Bodhi, 1993, p. 4); he wanted to help people live happier lives (Dalai Lama & Cutler, 1998). The differences mirror those found in psychology today. Many psychologists are researchers whose goal is to expand scientific knowledge about people, the mind, and the brain. But thousands of others, like the Buddha, work on a practical goal. They apply psychological knowledge—

What do you think is the value of seeking knowledge for knowledge’s sake?

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?

Question 8

In what way(s) was Aristotle like a modern psychologist? Which statements in the following list apply?

He systematically formulated ideas about the mind–

body connection. He answered questions using scientific methods.

He was interested in classification.

He was interested in the causes of emotional suffering.

He proposed a therapeutic technique for reducing emotional suffering.

Question 9

In what way(s) was the Buddha like a modern psychologist? Which statements in the preceding (same) list apply?

Jumping Ahead 2000 Years: Locke, Kant, and “Nature Versus Nurture”

Preview Question

How did the philosophers Locke and Kant believe that humans acquire knowledge?

How did the philosophers Locke and Kant believe that humans acquire knowledge?

We’re now going to jump ahead by two millennia from the time of Aristotle and the Buddha. It’s quite a jump—

“NATURE VERSUS NURTURE.” The distinction between nature and nurture pertains to the origin of psychological characteristics. Where did our beliefs, our abilities, and our likes and dislikes come from? Two possibilities are:

Nature: Nature (used in this context) refers to a biological origin of psychological characteristics. Characteristics that you have thanks to nature are ones you inherit; they are part of your genetic makeup. Colloquially, one says that they are “hard wired.”

Nurture: Nurture, which means “to educate or bring up” (think “nursery school”), refers to the development of abilities through experiences in the world. Abilities that come from nurture are those you learn rather than inherit.

Nature undoubtedly is the source of some behaviors: coughing, sneezing, putting your hand out in a fraction of a second to break your fall if you slip on ice. Nobody had to teach you these things. Nurture clearly is the source of other actions: driving, cooking, riding a bicycle. You acquired these skills through experience. But many other cases are less clear. The relative significance of nature and nurture has been debated since the seventeenth century, when it was explored by John Locke.

What are some things you’re engaged in right now that could only have been learned by experience (nurture)? Which ones are “hard wired” (by nature)?

LOCKE. John Locke was a British philosopher who produced his major work in the late 1600s, a remarkable time in world history. In the prior two centuries, Europe had experienced an intellectual rebirth—

By the time of Locke, scholars became optimistic that their era could unravel not only the mysteries of the physical world, but also the mysteries of the human mind. Locke took up the question “Where do people get their ideas; that is, what is the origin of concepts in the mind?”

Locke said that we get our ideas from experience; he argued for nurture, not nature. Ideas, he claimed, originate in our perceptions of the world. When we experience events, vision, hearing, and other senses bring information from the world into our minds. This experience-

At birth, one hasn’t yet had any experiences in the world. According to Locke, then, the mind at birth is a “blank slate”: a blackboard on which nothing has yet been written. It has the capacity to be written upon; nature provides the ability to learn. But nurture—

This conception of how we acquire ideas seems so obvious that you might wonder if anyone would question it. Someone did: a philosopher in eighteenth-

KANT. Kant knew that people learned from experience. But he did not think of the mind as a blank slate. Some ideas, he believed, are present in the mind from birth, thanks to nature.

Kant would acknowledge that, yes, experience teaches that if you decide to plunge your hand into a space occupied by a brick wall, your decision will cause pain a short time later. But, Kant would ask, how did you learn the concept of “time,” and the idea that some things happen “after” (later in time than) others? You can’t see time. It’s unlikely that, in childhood, your parents gave you a lecture on the nature of time. Yet concepts of time, and “before” and “after,” seem to be part of the mind at an early age.

Similarly, Kant would ask, where did you learn the concept of “space”—that objects are located in three-

Kant claimed that ideas such as space, time, and causality are innate: products of nature, not nurture. Kant, then, thought Locke got it wrong. The mind is not a blank slate. It contains some ideas at birth.

Had you ever before considered that the concept of time is innate?

Today, scientists continue to debate the nature–

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?

Question 10

When speaking of his son’s pitching talent, Steve brags he was “born with a golden arm.” Is Steve’s thinking more in line with Locke or with Kant?

Moving Into the Modern Era: Wundt and James

Preview Question

Why are Wundt and James considered the founders of scientific psychology?

Why are Wundt and James considered the founders of scientific psychology?

When discussing Aristotle, the Buddha, Locke, and Kant, we said that each was not a psychologist, in the contemporary sense of the term. Now let’s turn to the genuine article: psychological scientists.

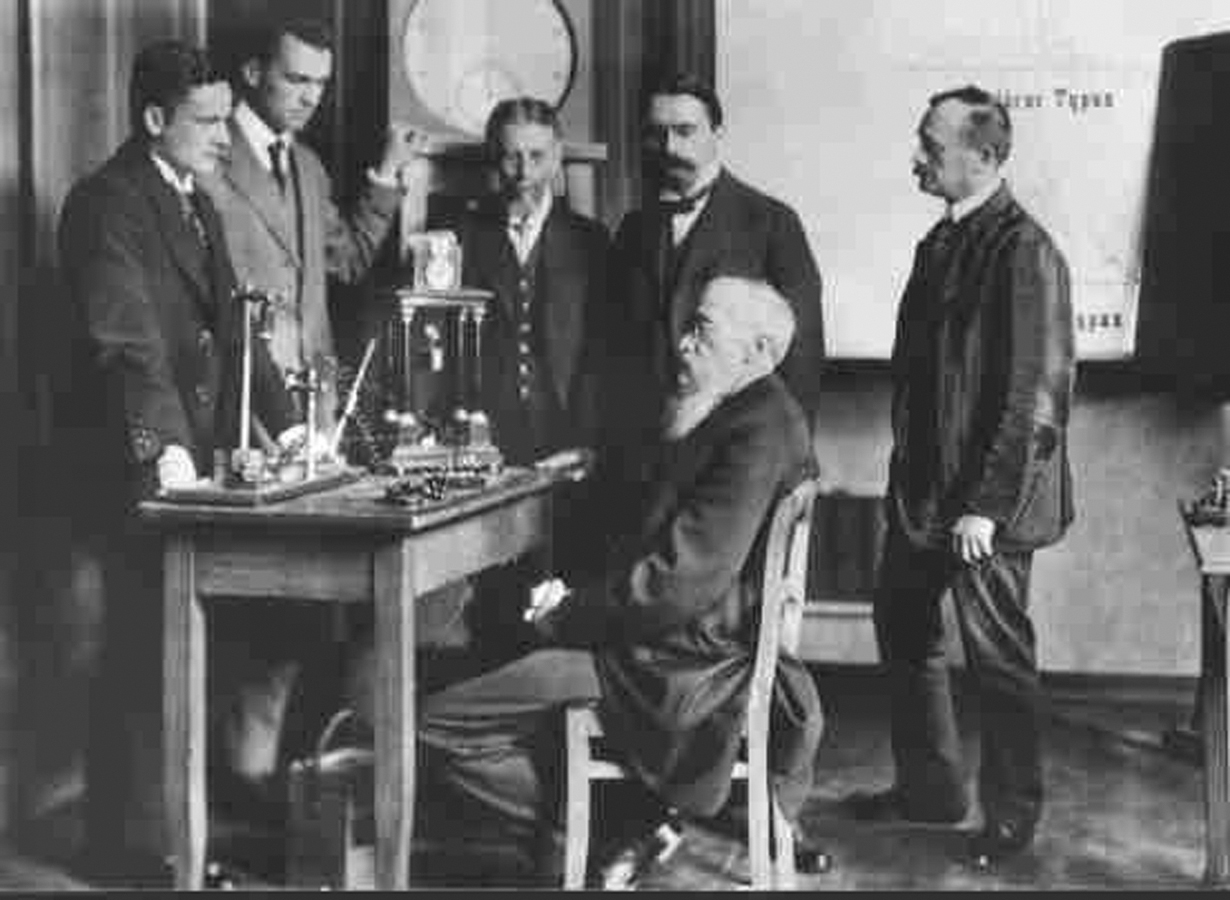

WUNDT. Scientific psychology has a definitive starting point: 1875, when Wilhelm Wundt arrived at the University of Leipzig as a professor and started the experimental research laboratory that was formalized as the Institute of Experimental Psychology in 1879 (Bringmann & Ungerer, 1980; Harper, 1950).

As a student, Wundt studied biology and earned a medical degree. But three factors turned his attention to psychology. One was sheer interest; studying the mind, he thought, was more interesting than treating patients (Wertheimer, 1970). A second was his knowledge of technical advances in science and medicine. Wundt recognized that newly invented devices for observing parts of the body (e.g., the interior of the eye, the vocal cords) could be used to study psychological functions (seeing, speaking). The third was Wundt’s knowledge of advances in the study of the nervous system. German scientists had developed experimental methods to study how the cells of the body’s nervous system work. Because, as Wundt knew, the brain and nervous system are the biological bases of the mind, the advances in biology held the promise of a successful experimental psychology (Watson, 1963).

Wundt, then, initiated this new field. To do so, he took two critical steps. He wrote Principles of Physiological Psychology, a book that combined biological knowledge with analyses of the mind. In particular, he explored the mind’s capacity for consciousness, that is, the capacity to perceive events in the world and to have feelings (Chapter 9). His second big step was to open his laboratory at the University of Leipzig (Harper, 1950). In his laboratory work, Wundt established procedures that would become standard throughout experimental psychology. He systematically varied the circumstances in which people performed tasks. He precisely measured aspects of their performance, such as the length of time it took them to solve problems (Robinson, 2002). In so doing, he pioneered the experimental methods we’ll discuss in Chapter 2.

Wundt’s lab attracted students from both Europe and the United States. When they returned home with their degrees, they spread knowledge of the new science of psychology. Wundt, deservedly called “the father of experimental psychology,” thus planted the seeds of today’s global psychological science community.

JAMES. Wundt was not the only person to open a psychological laboratory in 1875. Another opened in the United States, at Harvard University (Boring, 1929; Harper, 1950). In terms of research activities, it was more modest in scope. But its director was an intellectual giant: William James.

James suffered from a problem that plagues few of us. He had such a wide range of talents that he had trouble deciding what to do for a living. In the 1860s, he switched “from science to painting to science to painting again, then to chemistry, anatomy, natural history, and finally medicine” (Menand, 2001, p. 75). After earning his medical degree, he switched to psychology and began writing an introductory psychology book. (After finishing it, he changed fields again and became one of America’s greatest philosophers.)

James began his introductory psychology book in 1878. He thought he would finish it by 1880, but was off by a decade (Watson, 1963). The book grew “to a length,” James remarked, “which no one can regret more than the writer himself” (James, 1890, p. xiii). When published in 1890, it proved worth the wait. Many view James’s The Principles of Psychology as the greatest comprehensive volume in the history of the field (see Austin, 2013).

James’s book not only introduced the field, but defined it. In 1890 psychology’s scope was unclear; people didn’t know exactly what the field was, or could be. By perceptively analyzing a vast range of topics—

In his book’s final chapter, James addressed nature, nurture, and the views of Locke and Kant. He sided with Kant more than Locke, concluding that the mind at birth has a “native structure” (James, 1890, p. 889). Of particular importance, however, is not the content of James’s conclusion but how he reached it. James explained that the way to resolve the age-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?

Question 11

Wundt’s practice of systematically varying the circumstances in which people performed tasks and precisely measuring their outcomes marked him as the “father of psychology.” James’s agreement with Kant on the nature–

CULTURAL OPPORTUNITIES

Psychology Goes Global

In its early days, scientific psychology was a European and North American enterprise; the first laboratories and academic departments were established in western Europe and the United States. The field’s nineteenth-

It turned out not to be quite as global as one might have hoped. Of the approximately 400 people in attendance, three were from the United States, four from England, and three from Germany; the vast majority were from the home country of France (Benjamin & Baker, 2012). The early twentieth century saw greater interaction among American and European psychologists. However, the field was slow to expand beyond its European and North American base; psychology’s largest international convention, the International Congress of Psychology, was not held outside of Europe and the United States until 1972. Throughout much of its history, scientific psychology was not well informed by the scholars and cultural traditions of Asia, Africa, South America, and the Pacific (Berry, 2013).

Fortunately, matters have substantially changed in the twenty-

This global scope brings great opportunities—

You will see these advances throughout this book, most notably in each chapter’s Cultural Opportunities feature.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?

Question 12

What are two cultural opportunities afforded by an increase in the global scope of psychological science?

Schools of Thought

Preview Question

What characterizes six of the most prominent schools of thought in psychology?

What characterizes six of the most prominent schools of thought in psychology?

Most scientific activity in psychology today is problem-

Psychologists provided diverse answers to these questions. The field thus contained alternative schools of thought, that is, general approaches to building a psychological science. Let’s review six of them. The first two, which we will consider together, are structuralism and functionalism.

STRUCTURALISM AND FUNCTIONALISM. The distinction between structuralism and functionalism in psychology is best understood through an analogy to biology (Titchener, 1898). Biologists can study the body in either of two ways. Dissection reveals the body’s structures (bones, soft tissue, fluids). Study of the body in action reveals its functions, that is, what it does (digestion, respiration, and so forth). A similar distinction can be drawn in psychology.

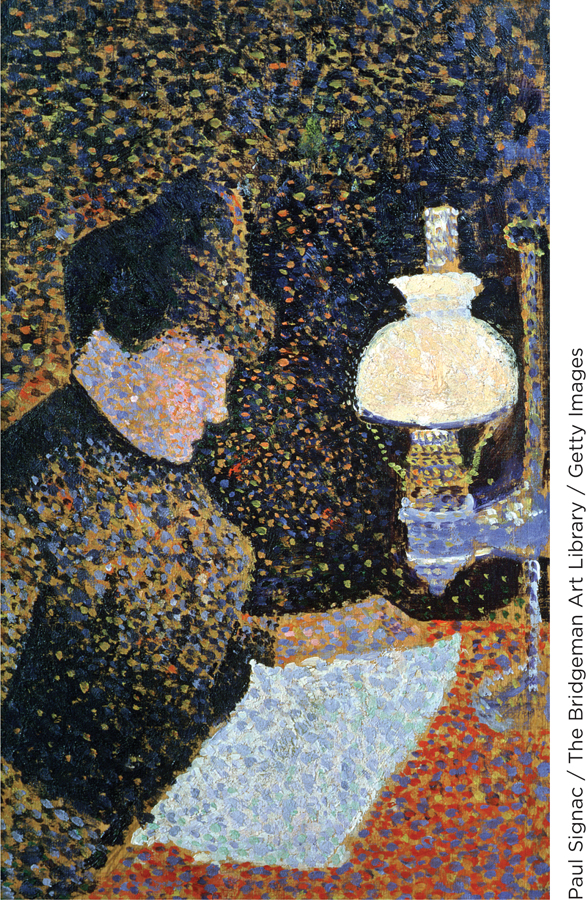

Structuralism is a school of thought that emphasized study of the mind’s basic components, or structures. Structuralists said that complex mental experiences were made up of simple, elementary components of the mind (Titchener, 1898). Like ingredients combined in a cake recipe, components of the mind combine to form an overall mental experience. Suppose, for example, that you look at a painting. You have one overall mental experience (“Hey, I like that weird smile on Mona Lisa”). This experience, structuralists would say, combines basic mental elements such as perception (you perceive patterns of light and color) and feelings (you like the picture). Perception and feeling, then, would be basic structures of the mind.

Functionalism emphasizes study of the mind in action. Functionalists were interested in what the mind does—what it’s good for—

Proponents of structuralism and functionalism recognized that both schools of thought would contribute to psychology’s growth (Watson, 1963). Their differences, then, were merely differences in emphasis. People disagreed on where psychologists should devote most of their efforts when forging the new field.

PSYCHOANALYSIS. Structuralism and functionalism developed in psychology departments in European and American universities. A third school of thought developed in the late nineteenth century outside of academia—

Sigmund Freud developed a school of thought known as psychoanalysis. As we detail in Chapter 13, psychoanalysis claims that the mind contains different parts (Freud, 1900, 1923). The parts are in conflict with one another. For example, one part contains sexual impulses, whereas another contains social rules that prohibit people from acting on their sexual impulses. Freud claimed that people are not fully aware of these conflicts; much of mental life occurs outside of awareness, or is unconscious.

Freud developed a theory of human nature and a therapy for treating psychological disorders, both of which had enormous impact on society. Yet within the science of psychology, Freud’s work was—

BEHAVIORISM. Behaviorism differed strikingly from structuralist, functionalist, and psychoanalytic approaches to studying the mind. The big difference was that, according to behaviorism’s founder, John Watson, psychologists shouldn’t study the mind at all. Watson (1913) declared behaviorism to be a school of thought whose sole focus is the “prediction and control of behavior” (p. 158). By behavior, Watson meant observable actions—

The psychologist B. F. Skinner (1953) developed a slightly different version of behaviorism. Like Watson, Skinner emphasized the study of behavior, but he defined “behavior” to include thinking and feeling. Skinner’s behaviorism thus analyzed the full range of psychological experiences. In Skinner’s analysis, the ultimate cause of all behavior—

Behaviorists believed that the processes through which the environment shapes behavior are universal—

Behaviorism added scientific rigor to psychology. But many felt it had a second influence that was detrimental: By studying rats, behaviorism deflected attention from the unique qualities of human beings. This critique motivated a school of thought known as humanistic psychology.

HUMANISTIC PSYCHOLOGY. Humanistic psychology is an intellectual movement which argues that the everyday personal experiences of human beings—

To you, early in your first course in psychology, this point might seem obvious. Aren’t all psychologists interested in people’s experiences? But when humanistic psychologists surveyed psychology in the mid-

Humanistic psychologists addressed multiple challenges. Carl Rogers developed a humanistic theory of personality that centered on people’s experiences of themselves, or self-

An intellectual movement in the twenty-

Humanistic psychology is consistent with something else you can find in psychology today: this book. Humanistic psychologists argued that the experiences of people, who live complex lives and contemplate the lives they live, are psychology’s ultimate target of investigation. They were right. Throughout this book, we strive to show how each of the diverse areas of psychological science illuminates the lives and experiences of people. Our primary tool to accomplish this is the book’s person-

The latter decades of the twentieth century witnessed scientific advances that enabled psychologists to combine knowledge of people with information about the workings of the mind and brain. Many of these advances were spurred by the final school of thought to be discussed here, information-

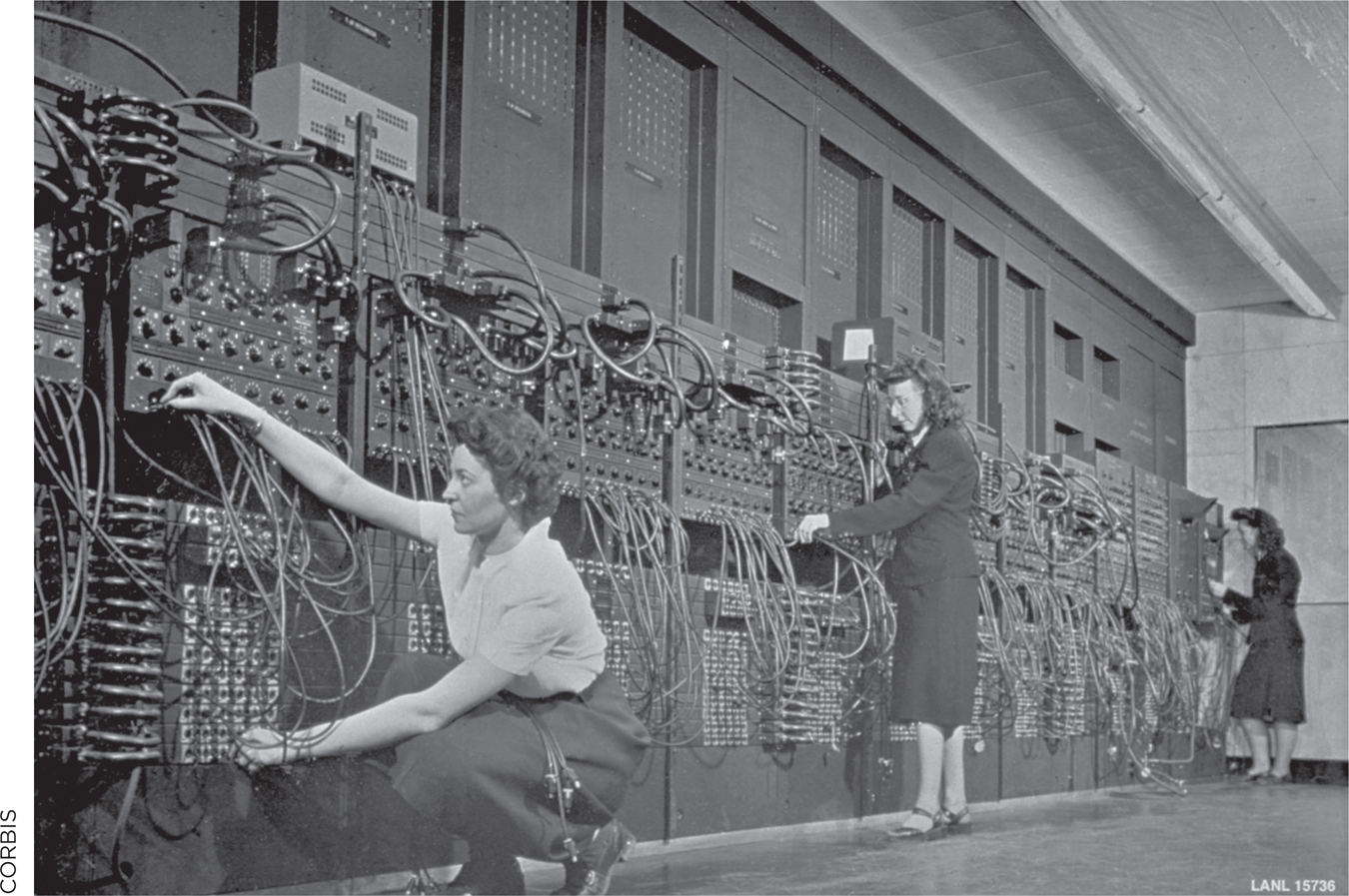

INFORMATION PROCESSING AND THE COGNITIVE REVOLUTION. Behaviorists cautioned against studying the mind. They asserted that any analysis of thinking processes—

This reasoning launched an intellectual revolution in psychology in the late 1950s (McCorduck, 2004; Miller, 2003). The cognitive revolution argued that the mind’s ability to acquire, retain, and draw on knowledge could, and should, be central to psychological science.

But how, exactly, could the mind be studied? Many researchers during the cognitive revolution studied the mind by treating it as an information-

Today, psychologists recognize that the human mind and brain do not work exactly like a computer. For example, the physical brain changes when you repeatedly practice a thinking skill (Chapter 3), but the physical electronics of your computer do not change when you repeatedly run the same computer program. Nonetheless, the information-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?

Question 13

Match the school of thought with its major idea or area of interest.

Structuralism Functionalism Psychoanalysis Behaviorism Humanistic psychology Cognitive revolution | Psychologists should focus on the mind’s hidden conflicts. Psychologists should study what the mind does, rather than its isolated parts. Psychologists should study how different components of the mind come together to form mental experiences. The mind should be understood as an information- Psychology should be built on the study of observable behaviors. Psychologists should study the person as a whole. |

The computer is a member of an important family of artifacts called symbol systems. … Another important member of the family is the human mind and brain.

—Herbert Simon (1996, p. 21)