10.4 Emotion and the Brain

Now that you’ve learned about the psychology of emotion and mood, let’s move down a level of analysis to the biology. What systems in the brain enable humans to have a mind filled not only with thoughts, but also feelings? This question has been addressed since the dawn of experimental psychology. We’ll begin by looking back to the late nineteenth century.

Classic Conceptions of Body, Brain, and Emotion

Preview Questions

Question

Do we first have to experience bodily arousal in order to experience an emotion?

Do we first have to experience bodily arousal in order to experience an emotion?

Are all emotions produced via the same process, and according to a step-

Are all emotions produced via the same process, and according to a step-

JAMES–

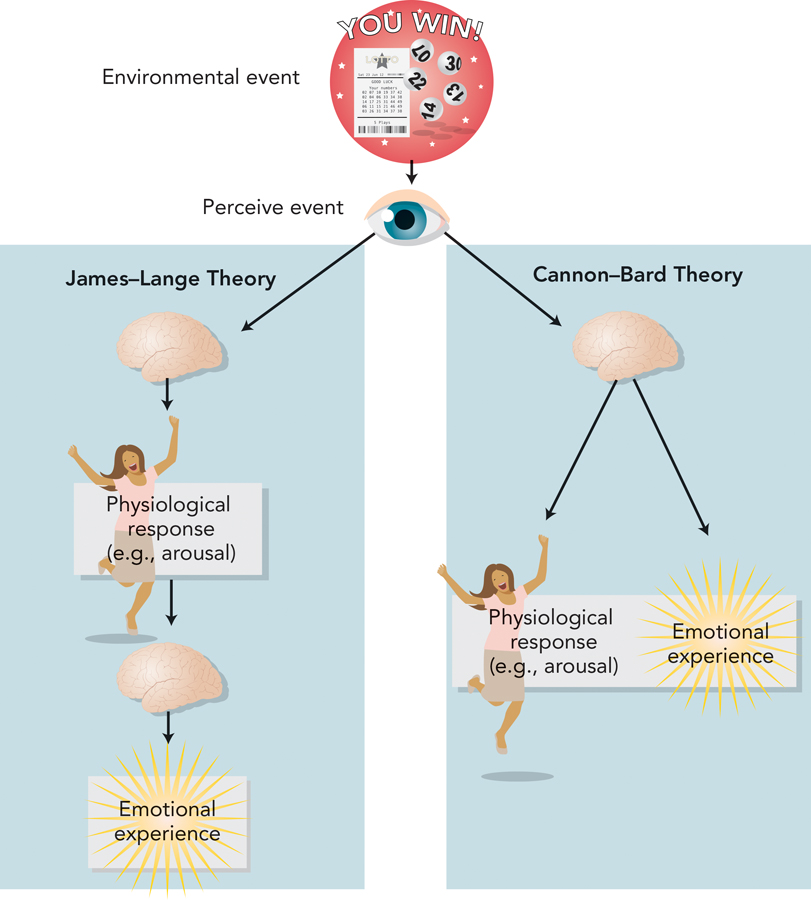

Intuitively, it seems that emotions cause physiological arousal: You experience an emotion (e.g., fear), which causes your bodily arousal to increase. But James and Lange thought this conception was backwards. The James–

The James–

Years later, two psychologists added a component to the James–

CANNON–

According to the Cannon–

Cannon and Bard rejected the James–

THINK ABOUT IT

Is one of these theories of emotion (James–

CONTEMPORARY STATUS OF THE CLASSIC THEORIES. James, Lange, Cannon, and Bard’s contributions were significant in their days. Those days, however, were long ago. Contemporary advances highlight two main limitations of both the James–

Both theories tried to identify the way in which emotion is generated. But there may be no one way in which emotion is generated. Some emotions may arise through one type of psychological process, whereas others arise through some other process. Contemporary researchers recognize that multiple processes contribute to emotional experience (LeDoux, 1994; Pessoa & Adolphs, 2010).

A second limitation is that both theories depict a step-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 12

True or False?

One criticism of the James–

Lange and Cannon– Bard theories of emotion is that they treat all emotions as if they arise through the same processes. A. B. Another criticism of the James–

Lange and Cannon– Bard theories of emotion is that they are not sequential enough; rather, they assume that brain events leading to emotional experiences happen simultaneously. A. B.

The Limbic System and Emotion

Preview Question

Question

What subcortical brain structures are key to emotional life? How do we know?

What subcortical brain structures are key to emotional life? How do we know?

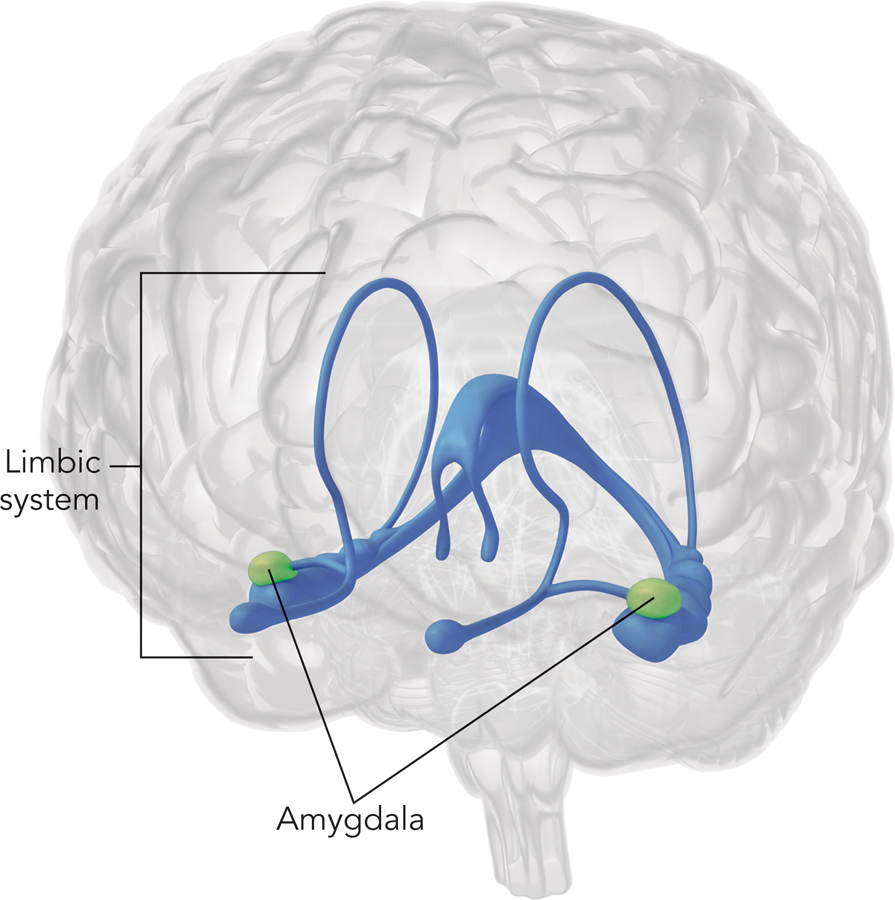

One region of brain that is key to emotional life is the limbic system. The limbic system is a set of brain structures residing below the cortex and above the brain stem (see Chapter 3). Limbic system structures are involved in the processing of rewarding, punishing, and threatening stimuli whose presence generates emotional reactions.

THE AMYGDALA. A structure within the limbic system that is particularly important to emotional response is the amygdala (Gallagher & Chiba, 1996; Hamann, 2011; Figure 10.14). The amygdala plays multiple roles in emotional experience and is particularly active in processing events that have the power to generate negative emotions such as fear.

One function of the amygdala is to detect stimuli that might be threatening to the organism. These stimuli often involve novelty; in general, familiar people and places are less threatening than novel ones. Brain-

Research on people with damage to the amygdala provides further evidence of its role in processing emotional information. Such people can recognize the identity of others but have difficulty identifying emotions expressed in others’ faces (Adolphs et al., 1994).

THE CASE OF SM. The amygdala plays a role not only in recognizing threatening stimuli, but also in generating the emotion of fear. Evidence of this comes from a remarkable case—

SM is a woman who has experienced bilateral amygdala damage, that is, damage to the amygdala on both the left and right sides of her brain. To learn about her experience of fear, experimenters (Feinstein et al., 2011) exposed her to stimuli that would scare almost anybody: handling a snake and a tarantula in a pet store; going to a haunted house; watching a scary movie. Other people found these stimuli quite scary—

What would your life be like without fear?

SM was not emotionless, however. When she saw the snakes and tarantulas, she showed interest. When she saw funny movies, she laughed. The deficit produced by her amygdala damage was highly specific: It eliminated only one emotion, fear. When researchers asked her to complete surveys of her emotions during daily life, she reported a full range of emotion—

Does SM’s case mean that the amygdala, by itself, produces the emotion of fear? No, not at all. Consider this analogy. If the thermostat in your home is damaged, you can’t control your home’s temperature. But the thermostat, by itself, does not produce the hot or cool air that maintains a home’s temperature. It’s just one component in a large system of parts. Analogously, if the amygdala in your brain is damaged, your emotional life is altered. Yet the amygdala is just one component in a large system of brain structures involved in emotional experience.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 13

The workings of the limbic system are better understood thanks to SM, a person with bilateral damage. She did not find snakes and tarantulas , as most would; as a result, she didn’t experience the emotion of .

The Cortex and Emotion

Preview Question

Question

How can we explain the psychologically complex phenomenon of emotional experience at the biological level of analysis?

How can we explain the psychologically complex phenomenon of emotional experience at the biological level of analysis?

If you think back to what you learned earlier in this chapter, you can figure out for yourself that emotion must involve brain structures beyond the amygdala. You learned that the psychology of emotion includes the following:

Thinking processes: Cognitive appraisals shape emotional experience.

Motor movements: Movements of facial muscles communicate emotions to others.

Consequences for motivation and decision making: Emotions affect our behavior and decisions.

In addition, you saw that these psychological components of emotion are highly coordinated. Your thoughts, feelings, facial expressions, and motives are synchronized. If you think you were insulted, you immediately feel angry; anger is immediately displayed on your face; and you immediately are motivated to act against the person who insulted you.

EMOTION AND INTERCONNECTED BRAIN SYSTEMS. These psychological facts have biological implications. The biological systems of emotion must be capable of explaining the psychological phenomena that you learned about. This means that the biology of emotion must include the following:

Brain structures involved in emotion-

related thoughts, motor movements, motivation, and decision making . It is known that many of the brain structures underlying thought, decision making, and behavior are not in the limbic system, but in the brain’s highest region, the cortex (see Chapter 3). The cortex, then, must play a big role in emotion.Interconnections among these brain structures. Brain structures in the limbic system and cortex must be highly interconnected. If they weren’t, then there couldn’t be such a high degree of synchronization among the various psychological components of emotion (thoughts, feeling, motivations, and facial expressions).

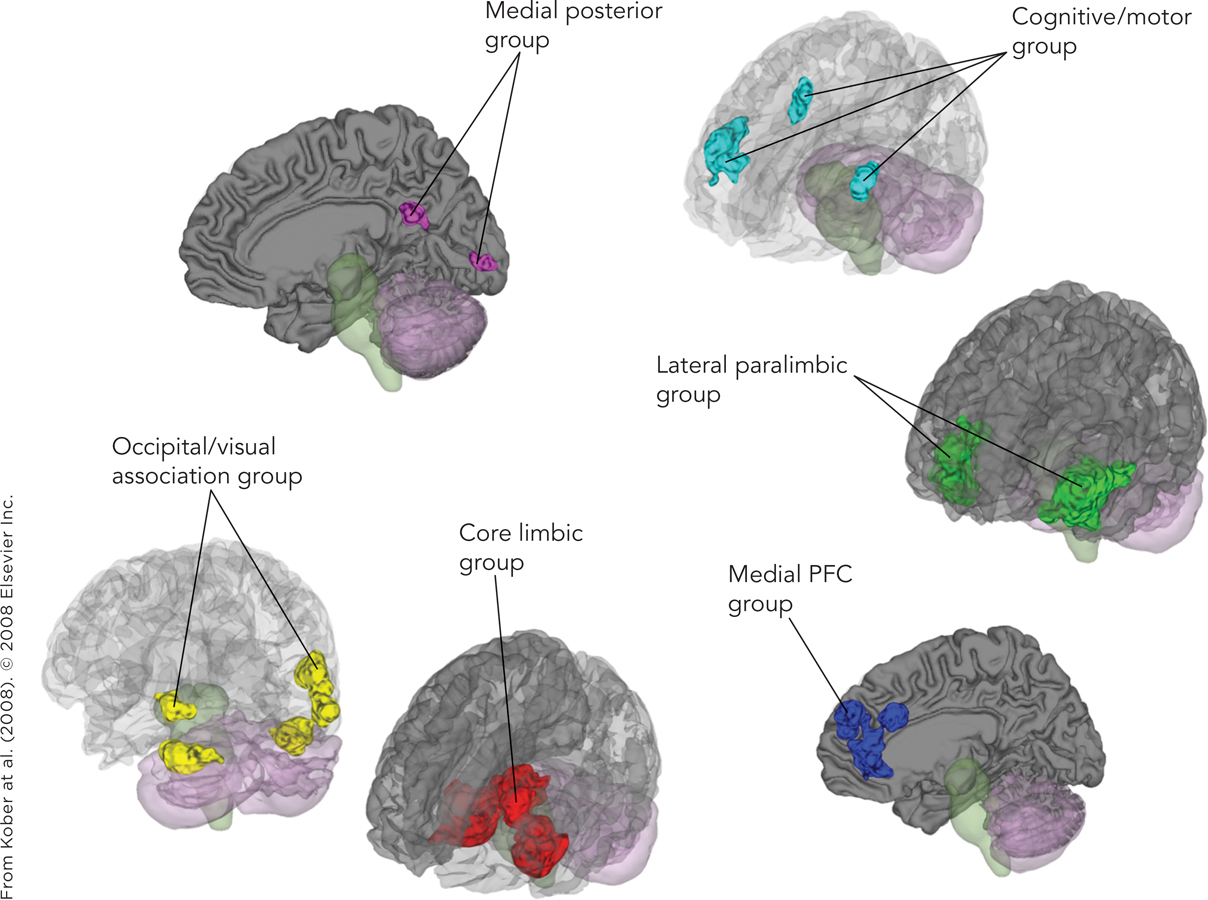

EVIDENCE FROM BRAIN-

Their results show that a complex network of brain structures contributes to emotion (Figure 10.15). Specifically, six interconnected groups of neural systems are involved. Two of them are in the limbic system, and the others are in the brain’s cortex. The latter include regions of the cortex that play a role in paying attention to stimuli, processing visual information, controlling motor movement, and planning one’s actions.

Furthermore, just as you’d expect from what you learned about the psychology of emotion, these brain systems of emotion were found to be highly interconnected. Activation in one region of the brain tended to co-

Research at a biological level of analysis, then, complements findings at a psychological level of analysis. Psychologically, emotions consist of a number of distinct components. These include both high-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 14

Match the fact about emotional experience on the left with its biological component on the right.

1. Emotional experience is complex and includes lots of different kinds of activities. 2. Cognitive appraisals shape emotional experiences. 3. There is synchronization among thoughts, feelings, motivations, and facial expressions. | One of the areas of the brain that is active during emotional experience is its highest region, the cortex, an area associated with thinking. The brain systems that are activated during emotional processing are highly interconnected. When people experience emotions, not one, but at least six neural systems are involved. |