Preface

A CONVERSATION WITH A COLLEAGUE LAUNCHED THIS BOOK. She said that, a couple weeks into the semester, a student in her introductory psychology class had asked, “Why are we learning about biology? I signed up for a psychology course.”

This, we realized, was a very good question.

The student understood the biology. But he couldn’t relate the biological facts—

Introductory psychology does not have to be like this. Students do not have to study genetic mechanisms before understanding the psychological qualities that people may inherit. They don’t have to memorize brain structures before learning about the psychological phenomena that researchers try to understand more deeply by studying the brain. Most important, they do not have to wait until their book’s closing chapters to encounter the topic of greatest interest to them: the experiences of people, living in a social world—

Our Pedagogical Strategy

Psychology: The Science of Person, Mind, and Brain was written to execute this strategy, and thereby to improve students’ learning experiences in introductory psychology. The strategy itself is relatively simple; it consists of two steps.

Levels of Analysis

The first step is a levels-

Person: The whole individual, who develops as a member of groups, a society, and a culture

Mind: Mental representations, cognitive processes, and affective processes with which the cognitive processes interact

Brain: The massively interconnected neural systems that make it possible for us to have minds and to be persons

Programs of theory and research conducted at person, mind, and brain levels of analysis are not “competing perspectives.” They are mutually complementary routes to scientific understanding. In combination, they make today’s psychology a multifaceted yet integrated science.

A levels-

A “Person-First” Approach

With three levels of analysis, one has to decide where to start—

Psychology: The Science of Person, Mind, and Brain consistently starts “at the top.” We introduce a person-

Solving Pedagogical Problems

This two-

(1) Enhancing Student Engagement. Students look forward to introductory psychology; it sounds like one of the most interesting courses in the curriculum. But they often come away disappointed. They hope to learn about human experiences but instead find themselves slogging through technical topics they cannot directly relate to questions about people. Many thus become less engaged.

I was one of them. When I took the course in college, I learned relatively little about what I had thought was the field’s main target of investigation: people. It wasn’t just that the research subjects frequently were pigeons, rats, or dogs. The larger problem was that, even when humans came into view, they were so dissected into parts—

Our person-

Greater student engagement, in turn, enhances learning. “Interest,” one researcher explains, “motivates learning about something new and complex…. New knowledge, in turn, enables more things to be interesting” (Silvia, 2008, p. 59). A person-

(2) Maximizing Student Comprehension. Comprehension is highest when readers possess an intellectual framework into which they can “place” new material (Kintsch, 1994). In traditional introductory psychology textbooks, students lack this intellectual framework when encountering some of the field’s most technical content. The course instructor knows, for example, how neurotransmitter functioning bears on emotional experience and how neural interconnections enable conscious experience. The instructor thus can easily place biological facts into a psychological framework. But the student usually cannot. This may impede comprehension and recall of the biological facts.

Comprehension could be enhanced if introductory textbooks revisited the “lower-level” details after presenting “higher-

Psychology: The Science of Person, Mind, and Brain addresses this problem directly. Our person-

(3) Coverage That Is Integrated. A third benefit of our person-

I now understand that psychology is not, in reality, a hodge-

Our levels-

(4) Critical Thinking. We all want our students to think critically—

A person-

(5) Coverage That Is Up-

Today’s hybrid fields—

Another up-

In sum, thanks to our person-

Executing the Person-First Mission

The primary means through which Psychology: The Science of Person, Mind, and Brain executes its pedagogical strategy is through its novel organization of material within chapters.

Organization of Within-Chapter Coverage

Our levels-

Chapters that focus primarily at a mind or brain level of analysis (e.g., Chapter 6: Memory, or Chapter 3: The Brain and the Nervous System) nonetheless begin at a person level. Individual case studies and person-

level research findings provide an introduction to material that is readily understandable and that illustrates the personal and social significance of the information- processing and biological mechanisms covered later in the chapter. Chapters that focus at a person or mind level include coverage of the brain. ( Psychology: The Science of Person, Mind, and Brain does not confine its coverage of neural systems to one chapter of the text.) The brain level of analysis, however, is introduced only after the psychological principals are established—

which enables readers to comprehend the psychological significance of the brain research. Furthermore, the brain- level coverage reinforces the learning of psychological- level material presented previously.

Let’s preview a few chapters to see how the strategy is executed:

Chapter 3: The Brain and the Nervous System Most brain chapters begin with the smallest unit of analysis: the individual neuron. Unfortunately, the introductory student rarely can fathom how the functioning of a neuron relates to the psychological experiences of a person. By contrast, we begin with person-

focused examples that illustrate two features of the brain as a whole: networks (i.e., interconnections within the brain) and plasticity (experience- driven changes in brain matter). Both are the focus of contemporary, cutting- edge research. Yet both make it easier for students to comprehend the brain and its relation to psychology, because they relate directly to everyday psychological experience. Up- to- date coverage thus goes hand- in- hand with student comprehension and engagement. Chapter 4: Nature, Nurture, and Their Interaction Chapters on nature, nurture, and genetics commonly begin by reviewing the gene’s molecular structure. For many students, this is a rehash of high school biology that appears unrelated to questions about psychological experience and social behavior. We begin instead with a study of gene-

by- environment interaction that shows how genes and socioeconomic settings both contribute to a well- known personal quality, intelligence. This personfocused example is scientifically up- to- date yet easily comprehensible. Students quickly grasp the psychological significance of the material in the chapter ahead. Page xxvChapter 11: Motivation All introductory psychology textbooks review motivation and basic biological needs (e.g., hunger). But much of today’s science of motivation encompasses social needs, as well as socially acquired thinking processes through which people can influence their own motivational states. Our person-

level focus brings the full range of motivational processes into view. This simultaneously enhances student interest (everybody is interested in influencing their own level of motivation) and yields coverage that is fully up- to- date. Chapter 14: Development Some chapters on developmental begin with biological content: the biology of conception, fetal development, and brain development in prenatal, childhood, and adolescent periods. In this format, students have difficulty connecting the biological facts to developmental psychology (which they haven’t learned about yet). By contrast, we begin with the psychology, covering cognitive development and the brain only after the psychological principles are established. As a result, the chapter begins with a psychological topic of inherent interest to students; the significance of the subsequent biological material is more readily apparent to them; and material in different sections of the chapter is integrated.

The opening two chapters of Psychology: The Science of Person, Mind, and Brain also advance the book’s unique pedagogical strategy. In Chapter 1, students see how a socially relevant problem (gender stereotypes and math performance) can be addressed at complementary person, mind, and brain levels of analysis. Chapter 2, Research Methods, covers techniques used to study the social behavior of people, the workings of the mind, and the neural and biochemical mechanisms of the brain.

Finally, opening vignettes are one more organizational feature that promotes the person-

Chapter 1’s opening vignette introduces the theme of the book. It shows students how a compelling social phenomenon, stereotype threat, can be understood at person, mind, and brain levels of analysis. As promised, students do not have to wait to encounter the lives of people living in the social world.

Modular Organization

A second means of promoting a person-

The chapters of Psychology: The Science of Person, Mind, and Brain are arranged into four parts. After Introduction (Chapters 1 and 2), they correspond to our three levels of analysis: Brain (Chapters 3–

The parts are modular; after the completion of Chapters 1 and 2, they can be read in any order. Modularity provides flexibility—

A key to the book’s modularity is found in Chapter 2, Research Methods. The chapter introduces not only research designs but also methods of data collection, including methods used in cognitive science and in brain research. This coverage provides readers with background sufficient to understand phenomena and research findings presented in all later chapters of the book.

Visualizing Person, Mind, and Brain Levels of Analysis

Two features visually reinforce our levels-

PMB in Action integrates material found within each chapter of the text. This full-

PMB Connections integrates material between chapters. Readers see how a topic addressed at a given level of analysis in one chapter is also addressed, at different levels of analysis, in other chapters. For example, in our chapter on social psychology, a PMB Connections visual highlights the personal experience of cognitive dissonance and then points to research on memory (the dissonant ideas must be stored and associated) and the brain (neural systems involved in memory and emotion must be connected) that bears on the person-

Enrichment Features

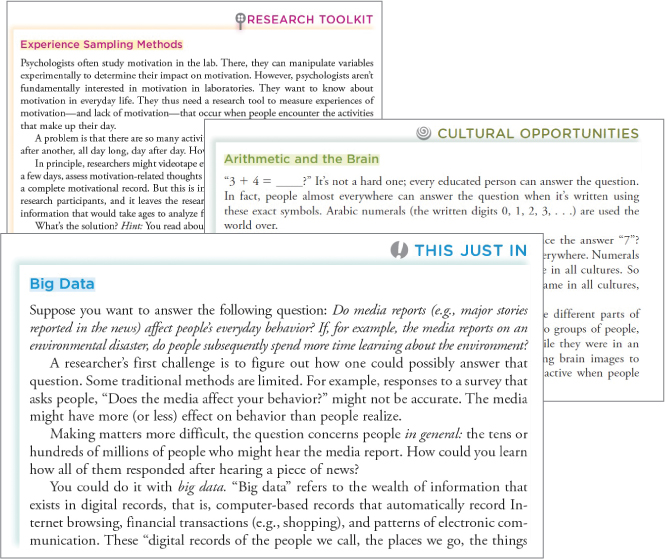

Each chapter contains enrichment features that expose readers to key topics in psychological science. These features are not “boxed” and thereby segregated from the flow of text, where they may be skipped by readers. Instead, they are integrated into the narrative and placed at points where they deepen readers’ understanding of overall chapter material. Our three enrichment features are Research Toolkit, Cultural Opportunities, and This Just In.

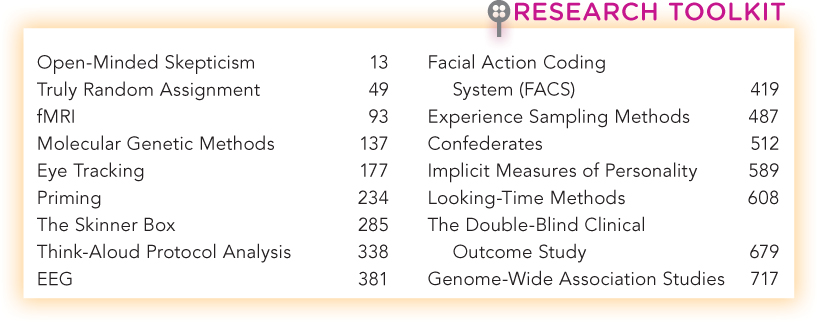

Research Toolkit

In each subfield of psychology, researchers employ specialized data-

Some textbooks compartmentalize research methods, with all discussion of methodology appearing in one early chapter. The drawback is plain to see. Early in the semester, students are unfamiliar with the substantive scientific questions that the methods are designed to answer.

Rather than compartmentalizing methods coverage, Psychology: The Science of Person, Mind, and Brain distributes it throughout the text. In addition to a foundational research methods chapter (Chapter 2), each subsequent chapter of the text presents a research technique germane to that chapter’s topic. This is done in a Research Toolkit feature. Each Research Toolkit describes a scientific challenge, encourages students to think critically about it, and presents a research tool that provides a solution. The Research Toolkit thus covers methods where they can best be understood: within the context of the substantive psychological questions.

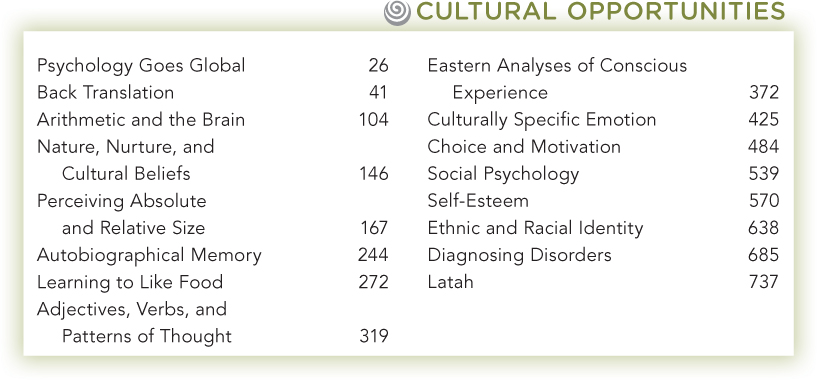

Cultural Opportunities

Some textbooks discuss culture in only one section of the book (e.g., within a social psychology chapter). This compartmentalization conflicts with the findings of today’s psychological science. Cultural beliefs and practices shape the developing person, the mind, and the brain—

In order to capture these scientific advances, each chapter of Psychology: The Science of Person, Mind, and Brain contains an enrichment feature called Cultural Opportunities. It showcases findings from the study of psychology and culture that address fundamental questions in psychological science.

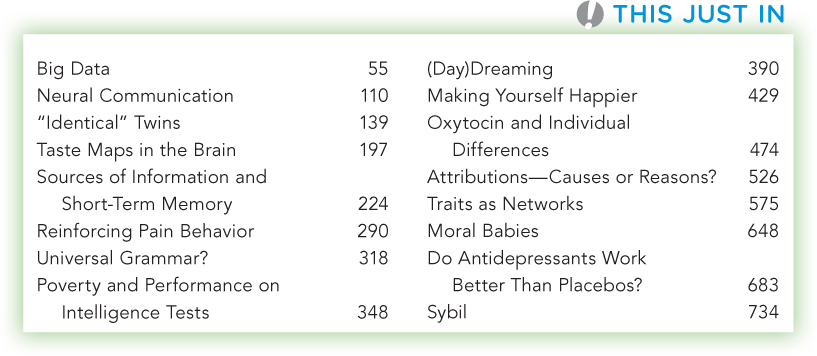

This Just In

We’re bombarded daily—

In addition to providing information about recent findings, This Just In teaches a more general lesson. The introductory student needs to understand not only that psychology is a science, but also that it is a rapidly evolving one. Advances in theory and research—

Integrated Media: Try This!

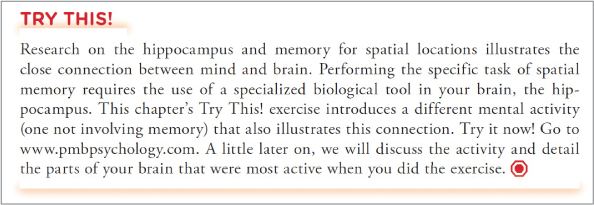

Psychology: The Science of Person, Mind, and Brain uniquely integrates the textbook experience with research experience. Readers take part in the methods of psychological science thanks to a feature called Try This!

In each chapter, readers are directed to our Web site, www.pmbpsychology.com, where they are invited to take part in a Try This! research experience. The Web site provides feedback on users’ own results and compares those results with published research findings. After readers return to the text, they learn more about the research experience in their subsequent reading.

Try This! creates a uniquely active textbook experience. Readers learn—

Pedagogical Program

In some textbooks, the pedagogical program is literally an afterthought—

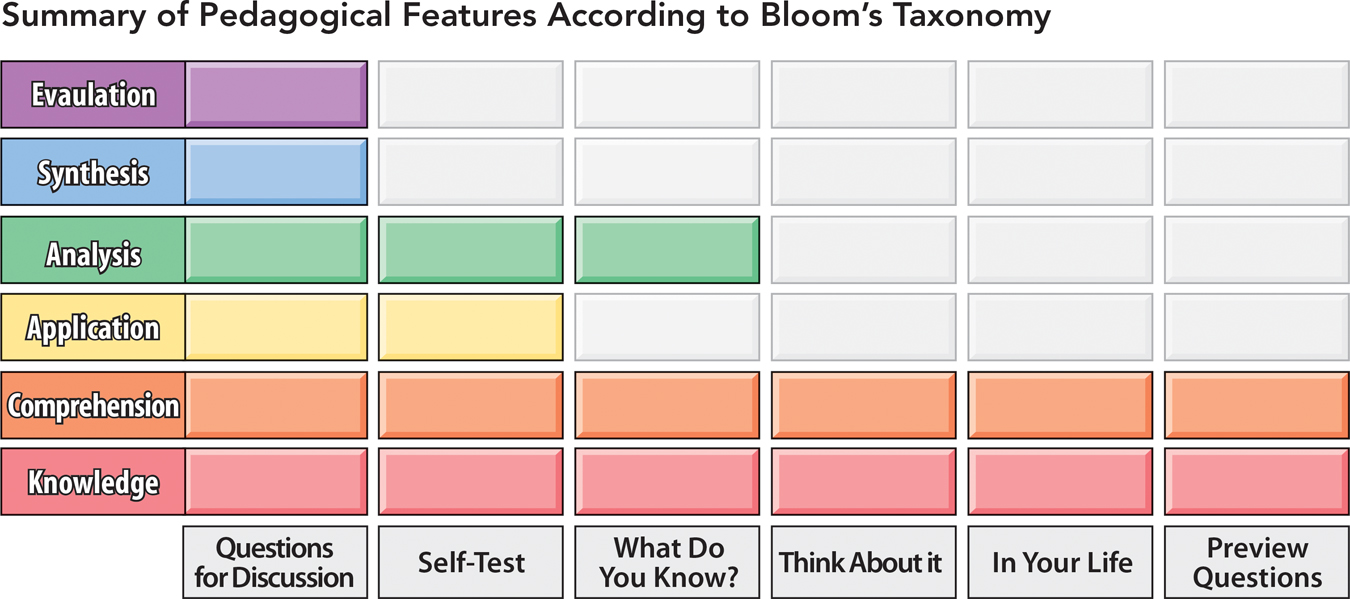

The pedagogy is designed around Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, a systematic enumeration of learning objectives developed by the educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom and revised subsequently by psychologists and education researchers (Krathwohl, 2002; Munzenmaier & Rubin, 2013). The objectives move far beyond the simple first goal of retaining knowledge of basic facts. As Bloom’s Taxonomy recognizes, course instructors want students to acquire deeper intellectual skills: comprehending material (interpreting its meaning and extrapolating beyond information provided), applying knowledge (e.g., using a concept to solve problems), analyzing information (breaking down complex phenomena into constituent parts), synthesizing material (generating a novel intellectual product by relating ideas to one another), and evaluating concepts and findings (judging their relative worth). These learning objectives—

Readers benefit from a range of pedagogical features that pursue various levels in this set of educational objectives:

Preview Questions placed before major chapter subsections pose questions that are answered in the reading. The questions highlight for readers upcoming points that are particularly important for study and comprehension.

Chapter Summaries repeat those questions and provide a set of answers that serve as a synopsis of each chapter as a whole.

Think About It asks students to pause and reflect on topics from the perspective of a psychological scientist —to question theoretical claims, interpretations of research, and the generalizability of research findings across social settings and cultures.

In Your Life questions that appear throughout each chapter help students identify applications of scientific material to their everyday lives. This feature reinforces the book’s consistent aim of showing readers the relevance of psychological science to everyday life.

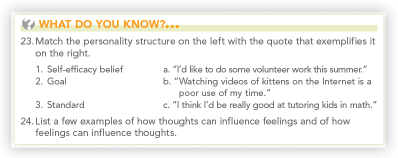

What Do You Know? assessments, which appear at the end of each section, give students an opportunity to immediately test their own learning. What Do You Know? questions typically target the knowledge and comprehension levels and occasionally the analysis level of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives.

Questions for Discussion found in end-

of- chapter material support the achievement of higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy— up through Level 6, Evaluation. The broad, open- ended Questions for Discussion, which can form the basis for class discussion, are a natural springboard to application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation— the critical thinking skills that comprise higher levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy. An end-

of- chapter Self- Test, consisting of 15 multiple-choice questions, is designed to challenge students through the first four Bloom’s Taxonomy levels.

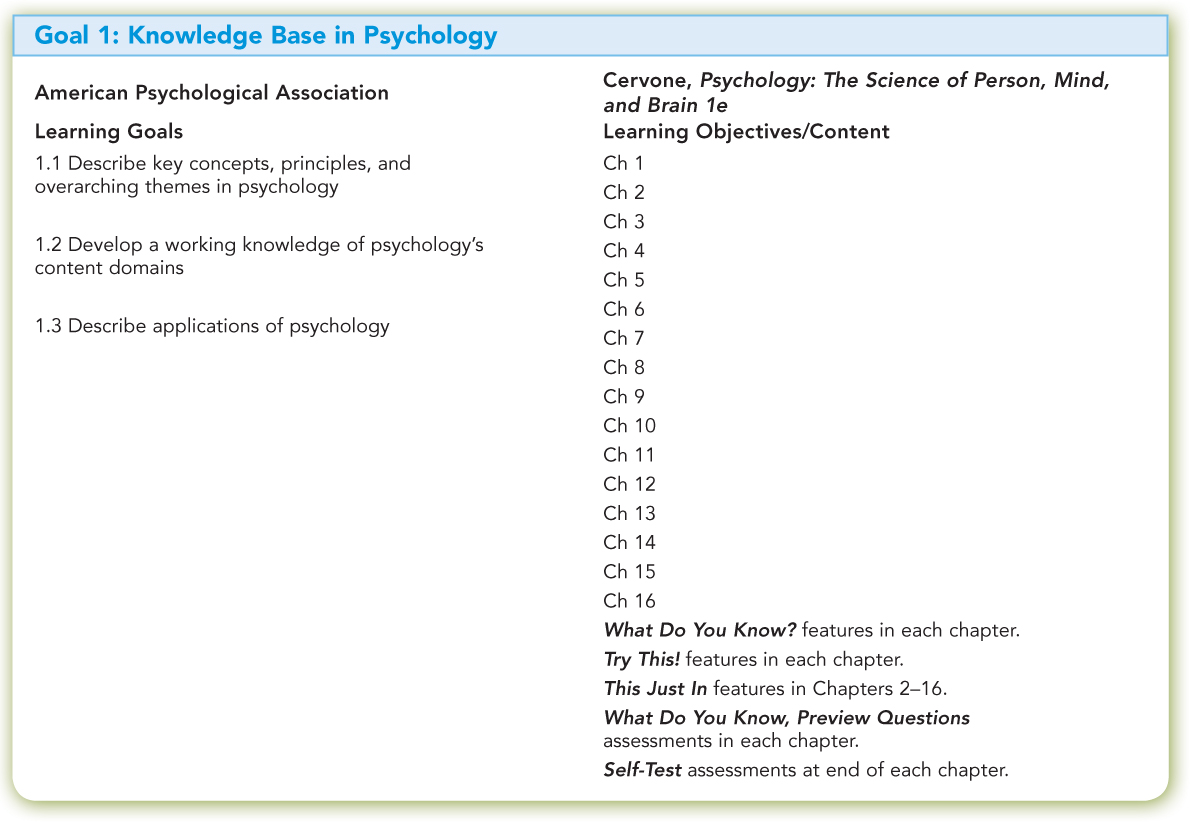

Alignment with APA Guidelines and MCAT 2015

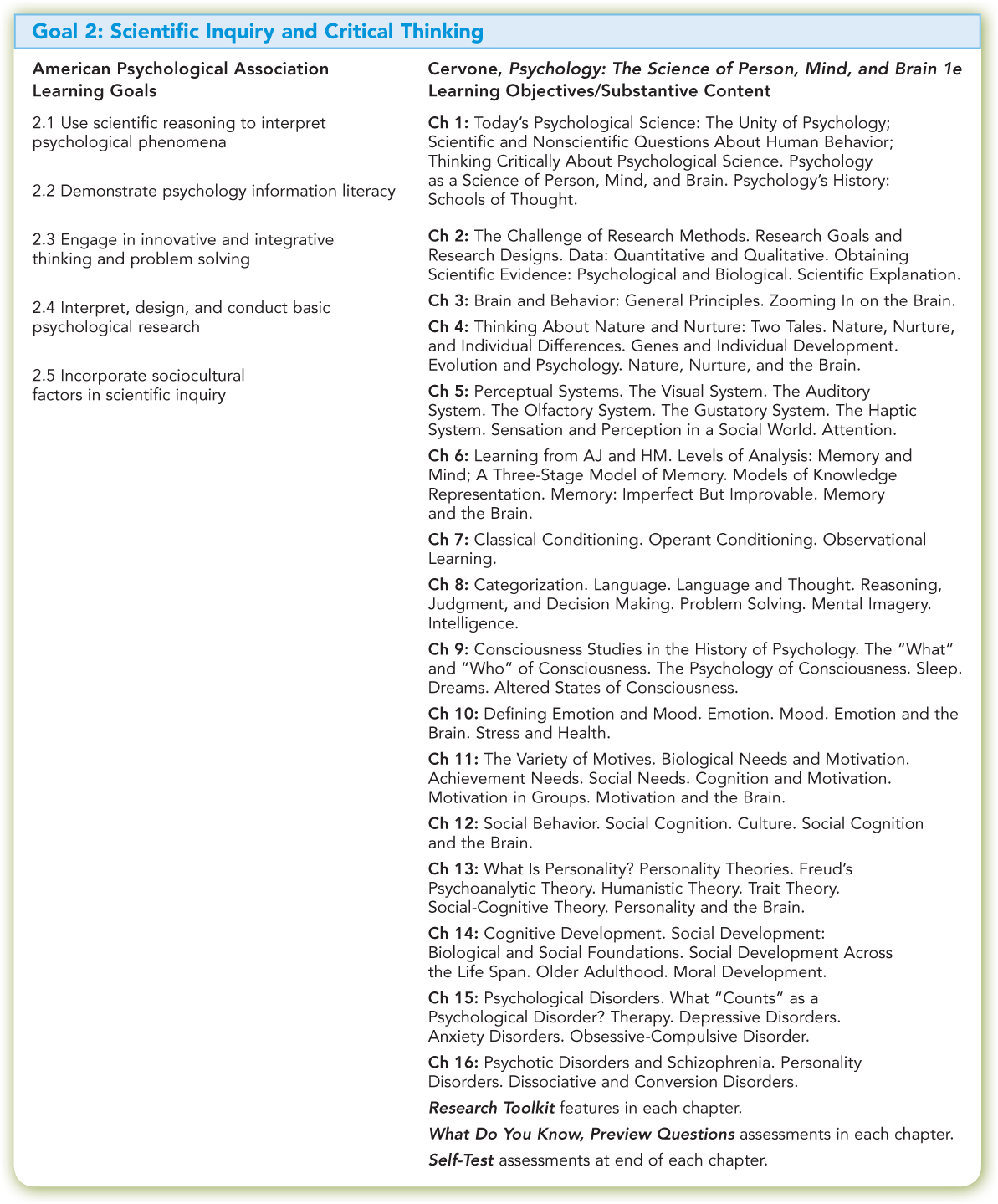

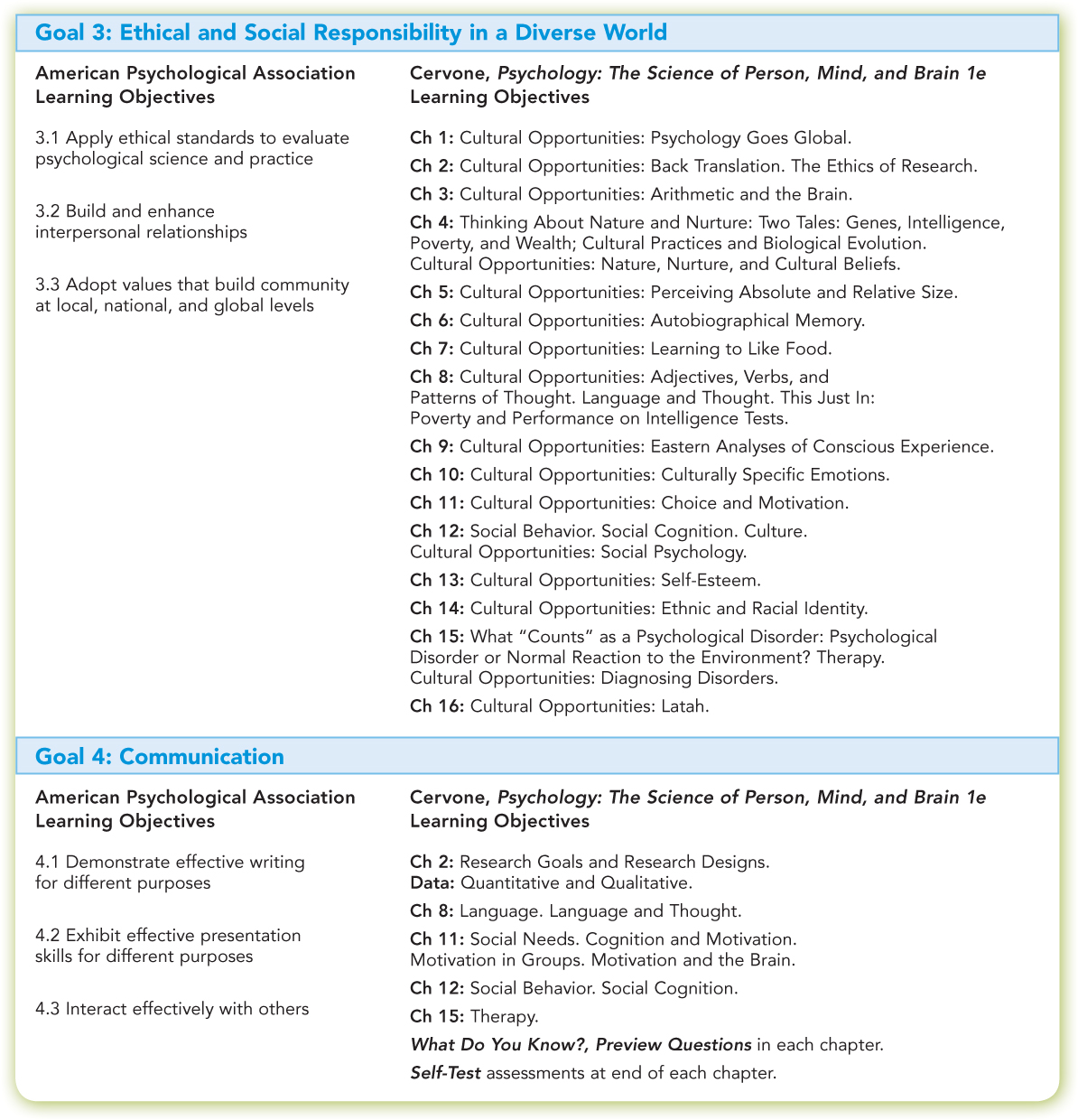

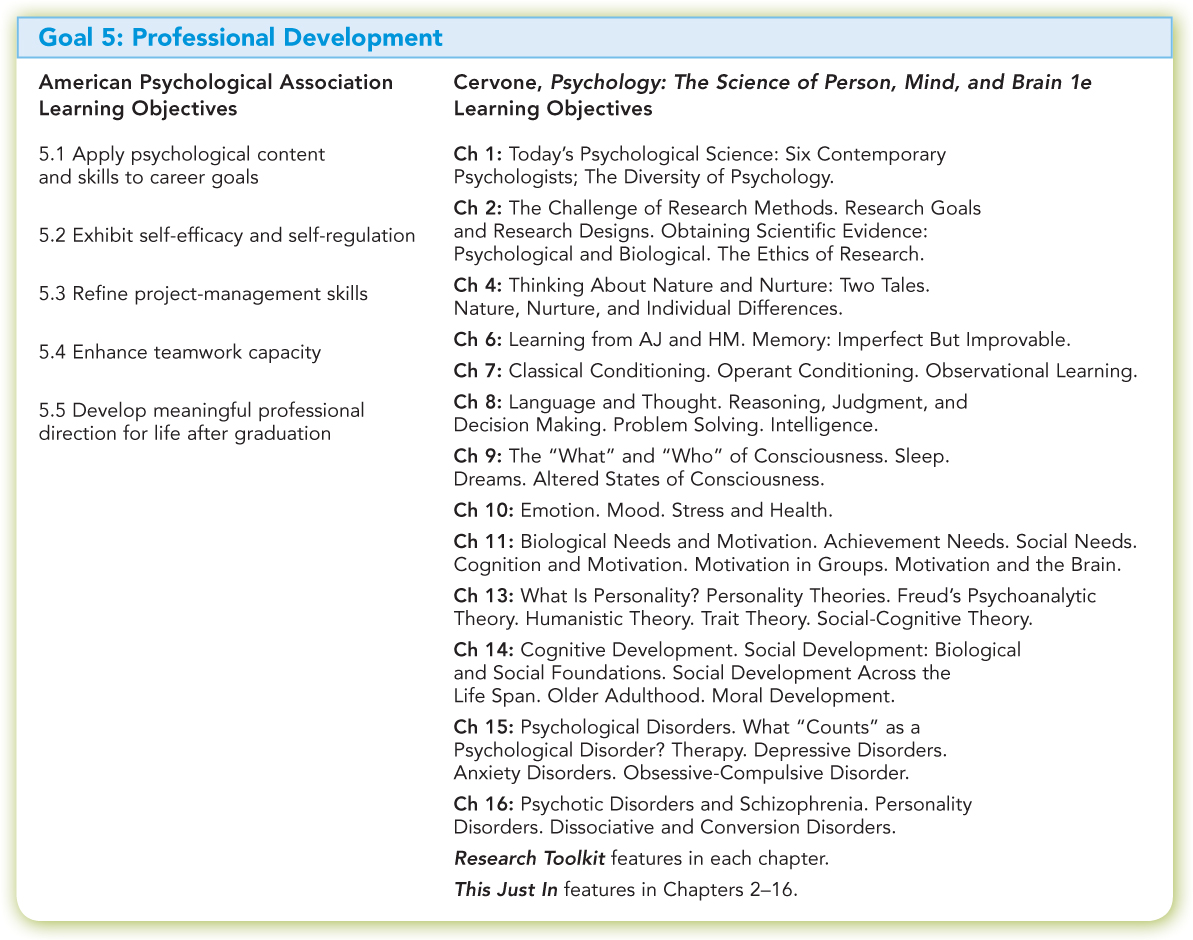

APA Learning Guidelines 2.0

In order to support students’ undergraduate experience in psychology as well as career development, the content in Psychology: The Science of Person, Mind, and Brain is aligned with The APA Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major 2.0. These guidelines present a rigorous standard for what students should gain from foundational courses as well as the complete major. A full concordance to the APA guidelines is posted in the Resources area of LaunchPad at www.macmillanhighered.com/

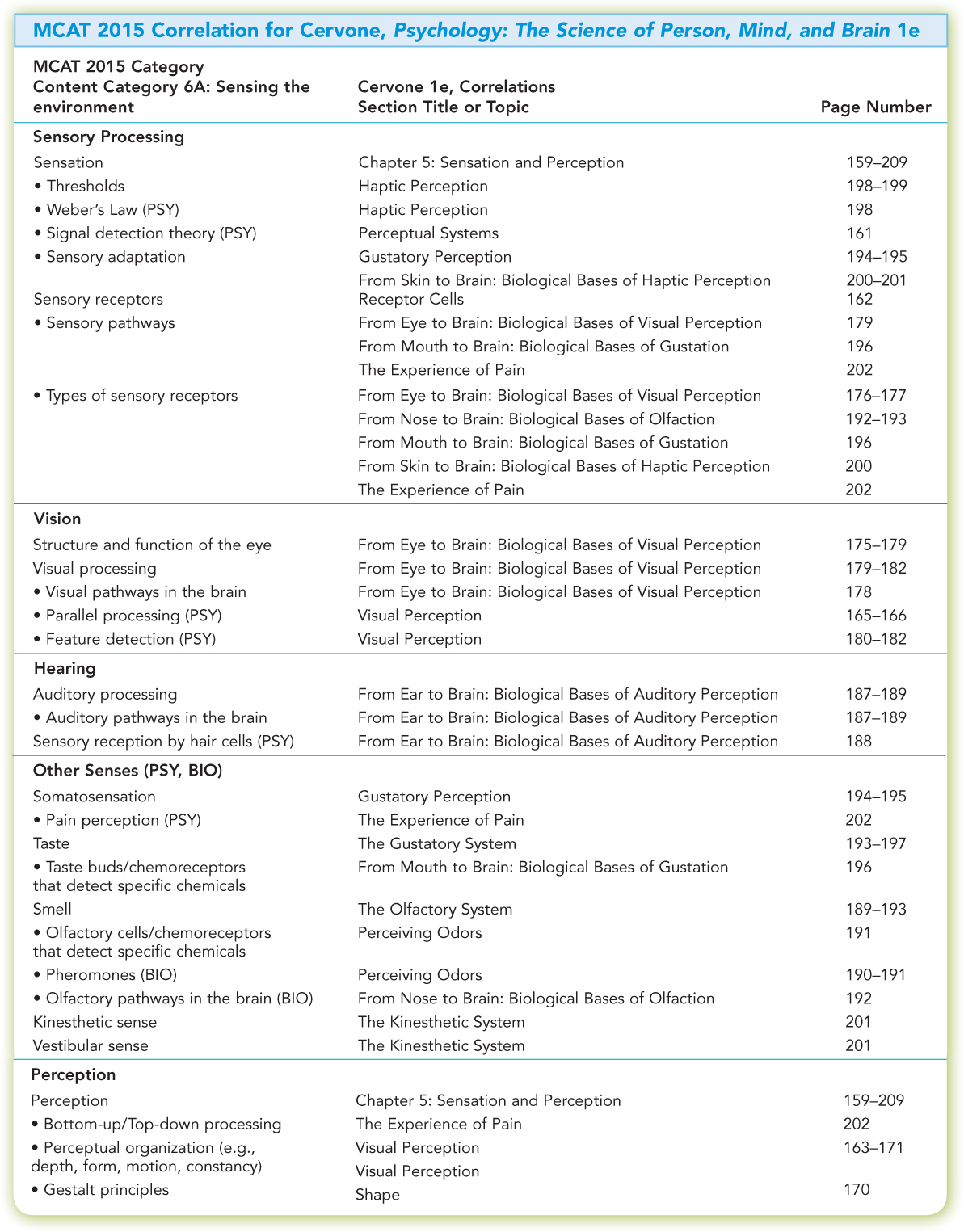

Psychology and MCAT 2015

The Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) began including test items assessing knowledge of psychology in 2015. One-

Thanks!

I once thought I’d employ the phrase “It takes a village” in this thank-

Jenny DeGroot and Nicholas DeGroot Cervone observed years of oddities. Most people don’t bring their work computer on “vacation.” Other parents were not typing rapidly during time-

Thanks also to family in Florida for kindly asking, “How is your book going?” at every holiday season. On a much more serious note, during the course of the writing, our family suffered a tragic loss that was attributable to a psychological disorder. Nothing can lessen the pain of such events. But they do motivate the author to craft a textbook that might inspire some readers to enter into and eventually advance this field in a way that may improve treatments for psychological distress (a motivation reflected in this book’s dedication).

Numerous individuals provided information to the author throughout the years of writing. Colleagues at the Department of Psychology at the University of Illinois at Chicago generously shared their knowledge of topics ranging from neurotransmitters to cognitive science to communities and cultures. Friends outside psychology have kept me up-

My experience teaching introductory psychology at UIC has greatly benefited the present work. Undergraduates’ moments of comprehension and puzzlement, interest and occasional boredom provided clues as to how best to structure material. Remarkably skilled graduate teaching assistants at UIC frequently shared insights into ways of enhancing undergraduate students’ engagement in, and comprehension of, psychological science.

I’d like also to acknowledge earlier academic experiences that placed me in a position to write this book. The faculty at Oberlin College provided an extraordinarily hands-

Four colleagues deserve special thanks. During our years of co-

Throughout the preparation of this book, we benefited from the insights of a large team of chapter reviewers and focus group attendees.

Carol Lynn Anderson

Bellevue College

Jessyca Arthur-

Manhattanville College

Josh Avera

De Anza College

Jeffrey Baker

Monroe Community College

Cynthia Barkley

California State University, East Bay

Dave Baskind

Delta College

Rinad Beidas

Temple University

Danny Benbassat

George Washington University

Joseph Benz

University of Nebraska at Kearney

Garrett Berman

Roger Williams University

Matthew Blankenship

Western Illinois University

John Broida

University of Southern Maine

Michelle Renae Byrd

Eastern Michigan University

Jessica Cail

Pepperdine University

Kevin M. Chun

University of San Francisco

Sheree Conrad

University of Massachusetts

Kristi Cordell-

Angelo State University

Ginean Crawford

Rowan University

Deanna DeGidio

Cuyahoga Community College Eastern Campus

Christopher Dehon

Monroe Community College

Daneen Deptula

Fitchburg State University

Nick Dominello

Penn State University

Dale Doty

Monroe Community College

Curtis Dunkel

Western Illinois University

Frederick Elias

California State University, Northridge

Renee Engeln

Northwestern University

Staussa C. Ervin

Tarrant County College, South

Todd Farris

Los Angeles Valley College

Dan Fawaz

Georgia Perimeter College

Diane Feibel

University of Cincinnati—

Adam Fingerhut

Loyola Marymount University

Donna Fisher Thompson

Niagara University

Claire Ford

Bridgewater State University

Alan Fridlund

University of California, Santa Barbara

Erica Gannon

Clayton State University

Marilyn Gibbons-

Southwest Texas State University

Bryan Gibson

Central Michigan University

Jennifer Gibson

Tarleton State University

Jamie Lynn Goldenberg

University of South Florida

Jennifer Gonder

Farmingdale State College, SUNY

Chris Goode

Georgia State University

Wind Goodfriend

Buena Vista University

Jeffrey Goodman

University of Wisconsin-

Cameron L. Gordon

University of North Carolina Wilmington

Ray Gordon

Bristol Community College

Jonathan Gore

Eastern Kentucky University

Raymond J. Green

Texas A&M University-

LaShonda Greene-

La Salle University

Sheila Greenlee

Christopher Newport University

Robert Guttentag

University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Shawn Haake

Iowa Central Community College

Meara Habashi

University of Iowa

Justin David Hackett

University of Houston-

Sowon Hahn

University of Oklahoma

Carrie Hall

Miami University (OH)

Deletha Hardin

The University of Tampa

Christian L. Hart

Texas Woman’s University

Mark Hauber

Hunter College

Erin Henshaw

Eastern Michigan University

Julie Hernandez

Rock Valley College

Sachi Horback

Bucks County Community College

Allen Huffcutt

Bradley University

Charles Huffman

James Madison University

Jack Kahn

Curry College

Donald Kates

College of DuPage

Julie Kiotas

Pasadena City College

Laura Kirsch

Curry College

Laura Knight

Indiana University of Pennsylvania

Tim Koeltzow

Bradley University

Gordon D. Lamb

Sam Houston State University

Mark Laumakis

San Diego State University

Natalie Lawrence

James Madison University

Marlene Leeper

Tarrant County College, Northeast

Kenneth J. Leising

Texas Christian University

Fabio Leite

The Ohio State University at Lima

Barbara Lewis

Susquehanna University

Christine Lofgren

University of California, Irvine

Nicolette Lopez

University of Texas at Arlington

Ben Lovett

Elmira College

Martha Low

Winston-

Pamela Ludemann

Framingham State University

Margaret Lynch

San Francisco State University

Amy Lyndon

East Carolina University

Jason Lyons

Tarleton State University

Lynda Mae

Arizona State University

Thomas Malloy

Rhode Island College

Michael Mangan

University of New Hampshire

Karen Marsh

University of Minnesota Duluth

Man’Dee Kameron Mason

Tarleton State University

Dawn McBride

Illinois State University

Todd J. McCallum

Case Western Reserve University

Yvonne McCoy

Tarrant County College, Northeast

Ticily Medley

Tarrant County College, South

Ronald Mehiel

Shippensburg University

Diana Milillo

Nassau Community College

Dan Miller

Indiana University—

Dennis Miller

University of Missouri

Robin Morgan

Indiana University Southeast

Laura Naumann

Sonoma State University

Bryan Neighbors

Southwestern University

Todd Nelson

California State University, Stanislaus

Glenda G. Nichols

Tarrant County College, South

Arthur Olguin

Santa Barbara City College

Lynn Olzak

Miami University (OH)

Charles Thomas Overstreet, Jr.

Tarrant County College, South

John Pierce

Villanova University

Thomas G. Plante

Santa Clara University

Laura Ramsey

Bridgewater State University

Heather J. Rice

Washington University in St. Louis

Vicki Ritts

St. Louis Community College, Meramec

Ronald Ruiz

Riverside City College

Shannon Rich Scott

Texas Woman’s University

Sandra Sego

American International College

Gregory Shelley

Kutztown University

Teow-

Sam Houston State University

Jesse Tauriac

Lasell College

Paul Thibodeau

Oberlin College

Felicia Thomas

California State Polytechnic University, Pomona

Donna Thompson

Midland College

Michelle Tomaszycki

Wayne State University

Jan Tornick

University of New Hampshire

Jose Velarde

Tarrant County College, Southeast

Jeffrey Wagman

Illinois State University

Nancy Woehrle

Wittenberg University

Brandy Young

Cypress College

Ryan Zayac

University of North Alabama

Zane Zheng

Lasell College

A huge thank-

A remarkable team of professionals at Worth Publishers is responsible for this book’s production. The energy and creativity of Senior Acquisitions Editor Dan DeBonis were crucial in bringing the project to fruition. Worth Publisher Rachel Losh, Assistant Editor Nadina Persaud, Editorial Assistant Katie Pachnos, and Managing Editor Lisa Kinne provided additional key support. The production process has also benefited from the work of Worth’s Director of Editing, Design, and Media Production for the Sciences and Social Sciences, Tracey Kuehn; Executive Media Editor, Rachel Comerford; and Production Manager, Sarah Segal. Preparation of the manuscript was speeded by the reference-

The writing has benefited from the skills of two exceptional Developmental Editors. Mimi Melek provided critical instructive feedback throughout the book’s early development. The subsequent contributions of Cathy Crow were so extensive, so constructive, and executed so efficiently that I cannot help but wonder if, in reality, a team of professionals was working under the pen name “Cathy Crow.”

Finally, thanks to two Worth professionals without whom we would not be here. Catherine Woods’s confidence in the project at its outset is deeply appreciated. Once under way, the work was nurtured for years by the wisdom and warmth of Kevin Feyen, who contributed immeasurably to the final product.

Acknowledgments

Although the main text of this book is sole-

These communications occurred shortly before Dr. Caldwell joined the faculty at Dominican. Because the assistant-

We jointly thank Worth Publishers for their incredible professionalism and support.

University of Illinois at Chicago