Monetary and Fiscal Policy in an Open Economy

How monetary and fiscal policy is affected by international trade and finance depends on the type of exchange rate system in existence. There are several ways that exchange rate systems can be organized. We will discuss the two major categories: fixed and flexible rates.

Fixed and Flexible Exchange Rate Systems

fixed exchange rate Each government determines its exchange rate, then uses macroeconomic policy to maintain the rate.

flexible or floating exchange rate A country’s currency exchange rate is determined in international currency exchange markets, given the country’s macroeconomic policies.

A fixed exchange rate system is one in which governments determine their exchange rates, then adjust macroeconomic policies to maintain these rates. A flexible or floating exchange rate system, in contrast, relies on currency markets to determine the exchange rates consistent with macroeconomic conditions.

Before the Great Depression, most of the world economies were on the gold standard. According to Peter Temin, the gold standard was characterized by “(1) the free flow of gold between individuals and countries, (2) the maintenance of fixed values of national currencies in terms of gold and therefore each other, and (3) the absence of an international coordinating organization.”1

Under the gold standard, each country had to maintain enough gold stocks to keep the value of its currency fixed to that of others. If a country’s imports exceeded its exports, this balance of payments deficit had to come from its gold stocks. Because gold backed the national currency, the country would have to reduce the amount of money circulating in its economy, thereby reducing expenditures, output, and income. This reduction would lead to a decline in prices and wages, a rise in exports (which were getting cheaper), and a corresponding drop in imports (which were becoming more expensive). This process would continue until imports and exports were again equalized and the flow of gold ended.

In the early 1930s, the U.S. Federal Reserve pursued a contractionary monetary policy intended to cool off the overheated economy of the 1920s. This policy reduced imports and increased the flow of gold into the United States. With France pursuing a similar deflationary policy, by 1932 these two countries held more than 70% of the world’s monetary gold. Other countries attempted to conserve their gold stocks by selling off assets, thereby spurring a worldwide monetary contraction. As other monetary authorities attempted to conserve their gold reserves, moreover, they reduced the liquidity available to their banks, thereby inadvertently causing bank failures. In this way, the Depression in the United States spread worldwide.

As World War II came to an end, the Allies met in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to design a new and less troublesome international monetary system. Exchange rates were set, and each country agreed to use its monetary authorities to buy and sell its own currency to maintain its exchange rate at fixed levels.

The Bretton Woods agreements created the International Monetary Fund to aid countries having trouble maintaining their exchange rates. In addition, the World Bank was established to loan money to countries for economic development. In the end, most countries were unwilling to make the tough adjustments required by a fixed rate system, and it collapsed in the early 1970s. Today, we operate on a flexible exchange rate system in which each currency floats in the market.

Pegging Exchange Rates Under a Flexible Exchange Rate System

Although most currencies fluctuate in value based on their relative demand and supply on the foreign exchange market, a number of countries use macroeconomic policies to peg their currency (maintain a fixed exchange rate) to another currency, most commonly the U.S. dollar or the euro.

A common reason for a country to peg its currency to another is to maintain a close trade relationship, because fixed exchange rates prevent fluctuations in prices due to changes in the exchange rate. For example, most OPEC nations peg their currencies to the U.S. dollar as a result of their dependency on oil exports, a significant portion of which goes to the United States. Many Caribbean nations that depend on tourism and trade with the United States also peg their currencies to the U.S. dollar.

Some countries do not maintain a strict fixed exchange rate with the U.S. dollar, but will intervene to control the exchange rate. For example, China has intervened in foreign exchange markets for strategic purposes, propping up the value of the U.S. dollar by holding dollars instead of exchanging them on the foreign exchange market. By keeping the U.S. dollar strong, the price of Chinese exports is kept low for American consumers, allowing China to continue expanding their export volume.

Another reason for maintaining a fixed exchange rate is to improve monetary stability and to attract foreign investment. For example, several countries in western Africa peg their unified currency, the CFA franc, to the euro. By maintaining a fixed exchange rate, a country is essentially giving up its ability to conduct independent monetary policy. However, some countries such as Mexico and Argentina, both of which had pegged their currencies to the U.S. dollar in the past, were forced to abandon their efforts due to high inflation, which made their products too expensive in world markets.

dollarization Describes the decision of a country to adopt another country’s currency (most often the U.S. dollar) as its own official currency.

Finally, some countries chose to abandon their currency altogether by adopting another country’s currency as their own. Panama, Ecuador, and El Salvador all chose to adopt the U.S. dollar as their official currency, a process known as dollarization. Not only did they give up their ability to use monetary policy, they also eliminated the risk of being unable to maintain fixed exchange rates with their original currencies.

There clearly are many approaches to foreign exchange used. But how does a fixed versus a flexible exchange rate system affect each country’s ability to use fiscal and monetary policy? We answer this question next.

Policies Under Fixed Exchange Rates

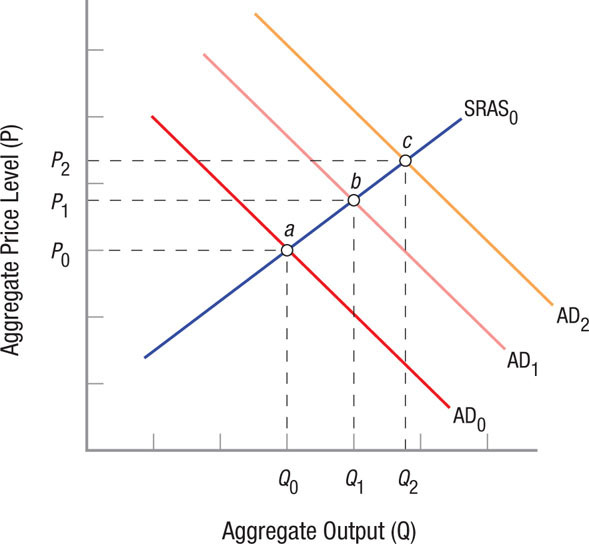

When the government engages in expansionary policy, aggregate demand rises, resulting in output and price increases. Figure 5 shows the result of such a policy as an increase in aggregate demand from AD0 to AD1, with the economy moving from equilibrium at point a to point b in the short run and the price level rising from P0 to P1. A rising domestic price level means that U.S. exports will decline as they become more expensive. As incomes rise, imports will rise. Combined, these forces will worsen the current account, moving it into deficit or reducing a surplus, as net exports decline.

FIGURE 5

Monetary and Fiscal Policy in an Open Economy When the government engages in expansionary policy, aggregate demand rises, resulting in output and price increases. A rising domestic price level reduces exports while rising incomes increases imports, worsening the current account.An expansionary monetary policy (holding fiscal policy constant), increases the money supply and reduces interest rates. Lower interest rates result in capital outflow, pushing the money supply back down and moving aggregate demand back toward AD0.

An expansionary fiscal policy (holding monetary policy constant), increases interest rates, leading to capital inflow, pushing aggregate demand further to the right to AD2.

An expansionary monetary policy, combined with a fiscal policy that is neither expansionary nor contractionary, will result in a rising money supply and falling interest rates. This causes aggregate demand to rise to AD1 as shown in Figure 5. Lower interest rates result in capital flowing from the United States to other countries. This reduces the U.S. money supply.

The greater the capital mobility, the more the money supply is reduced, and the more aggregate demand moves back in the direction of AD0. With perfect capital mobility, monetary policy would be ineffective. The amount of capital leaving the United States would be just equal to the increase in the money supply to begin with, and interest rates would be returned to their original international equilibrium.

Keeping exchange rates fixed and holding the money supply constant, an expansionary fiscal policy will produce an increase in interest rates. As income rises, there will be a greater transactions demand for money, resulting in higher interest rates. Higher interest rates mean that capital will flow into the United States.

As more capital flows into U.S. capital markets, interest rates will be reduced, adding to the expansionary impact of the original fiscal policy. Expansionary fiscal policy is reinforced by an open economy with fixed exchange rates as aggregate demand increases to AD2.

Policies Under Flexible Exchange Rates

Expansionary monetary policy under a system of flexible exchange rates, again holding fiscal policy constant, results in a growing money supply and falling interest rates. Lower interest rates lead to a capital outflow and a balance of payments deficit, or a declining surplus. With flexible exchange rates, consumers and investors will want more foreign currency; thus, the exchange rate will depreciate. As the dollar depreciates, exports increase; U.S. exports are more attractive to foreigners as their currency buys them more. The net result is that the international market works to reinforce an expansionary policy undertaken at home.

Permitting exchange rates to vary and holding the money supply constant, an expansionary fiscal policy produces a rise in interest rates as rising incomes increase the transactions demand for money. Higher interest rates mean that capital will flow into the United States, generating a balance of payments surplus or a smaller deficit, causing the exchange rate to appreciate as foreigners value dollars more. As the dollar becomes more valuable, exports decline, moving aggregate demand back toward AD0 in Figure 5. With flexible exchange rates, therefore, an open economy can hamper fiscal policy.

NOBEL PRIZE ROBERT MUNDELL

Awarded the Nobel Prize in 1999, Robert Mundell is best known for his groundbreaking work in international economics and for his contribution to the development of supply-side economic theory. Born in Canada in 1932, he attended the University of British Columbia as an undergraduate and earned his Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1956. For a year, he served as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Chicago, where he met the economist Arthur Laffer, his collaborator in the development of supply-side theory.

Supply-side economists advocated reductions in marginal tax rates and stabilization of the international monetary system. This approach was distinct from the two dominant schools of economic thought, Keynesianism and monetarism, although it shared some ideas with both. Mundell’s work had a major influence on the economic policies of President Ronald Reagan and Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker, whose tight money policies helped curb inflation.

Mundell’s early research focused on exchange rates and the movement of international capital. In a series of papers in the 1960s that proved to be prophetic, he speculated about the impacts of monetary and fiscal policy if exchange rates were allowed to float, emphasizing the importance of central banks acting independently of governments to promote price stability. At the time, his work may have seemed purely academic. Within ten years, however, the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates tied to the dollar broke down, exchange rates became more flexible, capital markets opened up, and Mundell’s ideas were borne out.

In another feat of near prophecy, Mundell wrote about the potential benefits and disadvantages of a group of countries adopting a single currency, anticipating the development of the European currency, the euro, by many years. Since 1974, Mundell has taught at Columbia University.

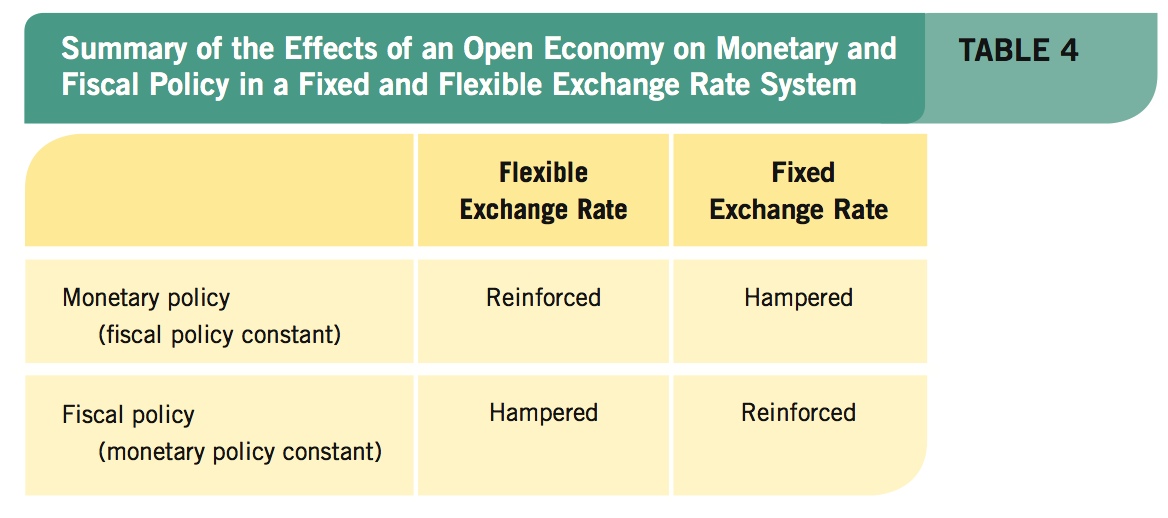

These movements are complex and go through several steps. Table 4 summarizes them for you. The key point to note is that under our flexible exchange rate system now, an open economy reinforces monetary policy and hampers fiscal policy. No wonder the Fed has become more important.

Several decades ago, presidents and Congress could adopt monetary and fiscal policies without much consideration of the rest of the world. Today, economies of the world are vastly more intertwined, and the macroeconomic policies of one country often have serious impacts on others. Today, open economy macroeconomics is more important, and good macroeconomic policymaking must account for changes in exchange rates and capital flows.

Would Flexible Exchange Rates in OPEC Nations Affect Oil Markets?

For several decades, many OPEC nations have pegged their currencies to the U.S. dollar as a way to facilitate trade of crude oil, their largest export, to the world market and especially the United States, one of their largest customers.

However, in the past decade, several OPEC nations, such as Kuwait, have moved off of the peg, choosing to let their currencies fluctuate and also to trade oil in other currencies including the euro. How would a move to flexible exchange rates affect international trade of goods and services, particularly oil?

The price of a barrel of crude oil is determined on world markets, typically in U.S. dollars. When the value of the dollar changes, the value of OPEC currencies pegged to the dollar remains the same, thereby preventing dramatic changes in oil prices resulting from exchange rate changes in the supplying country.

However, in recent years many countries, such as India and China, have increased their demand for oil. If the U.S. dollar depreciates against the Chinese yuan or Indian rupee, oil becomes cheaper for Indians and Chinese, all else equal. Therefore, a depreciation of the dollar would increase the demand for oil on world markets, pushing up prices that all consumers must pay. In sum, fluctuations in the value of the dollar affect oil prices from the demand side.

What would happen if more OPEC nations removed their currency peg? Initially, oil prices would likely not change too much as long as the value of the U.S. dollar does not deviate much. However, if the U.S. dollar faces a significant depreciation, the price of oil will rise because of its reduced purchasing power. This is what Kuwait wants.

In sum, the existence of fixed and flexible exchange rates carries important implications for the prices of imported and exported goods, which constitute a large percentage of economic activity in nearly all countries. Fixed exchange rates tend to stabilize the prices of traded goods as long as economies face similar levels of economic and monetary growth. Flexible exchange rates allow countries to adjust their policies to correct deficits or surpluses in their current accounts; however, the effect on the prices of traded goods, such as oil, can be more unpredictable.

During the financial crisis and recession of 2007–2009, the implications of monetary policy on exchange rates became important, as countries throughout the world were eager to use expansionary monetary policy to curtail the severity of the crisis. However, taking such action unilaterally can lead to adverse effects in other countries due to its effect on exchange rates, which affect trade and current accounts.

Therefore, in October of 2008, six central banks including the Fed and the European Central Bank took a rare action of coordinated monetary policy, in which the central banks jointly announced a reduction in their target interest rates. As a result, countries engaging in a similar level of expansionary policy would prevent instability in exchange rates. As Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke put it, “the coordinated rate cut was intended to send a strong signal to the public and to markets of our resolve to act together to address global economic challenges.”2 The coordinated efforts of central banks continued over several years, especially when the Eurozone crisis intensified in 2011.

The global economy is connected not only through trade and currency exchanges. Nearly all economic decisions have effects that extend beyond our country’s borders, from the types of goods that consumers purchase, to the goods firms produce and where they produce them, to how governments set policies that affect their citizens and those in other countries. As you complete your degree and prepare for your career, keep in mind the statement from Chapter 1 that has been illustrated throughout this book: Economics is all around us.

MONETARY AND FISCAL POLICY IN AN OPEN ECONOMY

- A fixed exchange rate is one in which governments determine their exchange rates and then use macroeconomic policy to maintain these rates.

- Flexible exchange rates rely on markets to set the exchange rate given the country’s macroeconomic policies.

- Some countries peg their currency to another to facilitate trade, to promote foreign investment, or to maintain monetary stability.

- Fixed exchange rate systems hinder monetary policy, but reinforce fiscal policy.

- Flexible exchange rates hamper fiscal policy, but reinforce monetary policy.

QUESTION: The United States seems to rely more on monetary policy to maintain stable prices, low interest rates, low unemployment, and healthy economic growth. Does the fact that the United States has really embraced global trade (imports and exports combined are over 30% of GDP) and has a flexible (floating) exchange rate help explain why monetary policy seems more important than fiscal policy?

As noted in this section, monetary policy is reinforced when exchange rates are flexible, while fiscal policy is hindered. This is probably only a partial explanation, because fiscal policy today seems driven more by “events” and other priorities, and less by stabilization issues.

The recent deep recession required heavy doses of both monetary and fiscal policy to keep the economy from a devastating downturn. Additional government spending, while huge, didn’t seem to pack the punch many thought it would. Maybe flexible exchange rates kept it from being as effective as anticipated.