NATIONAL INCOME ACCOUNTING

The national income and product accounts (NIPA) let economists judge our nation’s economic performance, compare U.S. income and output to that of other nations, and track the economy’s condition over the course of the business cycle. Many economists would say that these accounts represent one of the greatest inventions of the 20th century.3

3 William Nordhaus and Edward Kokkelenberg (eds.), Nature’s Numbers: Expanding the National Economic Accounts to Include the Environment (Washington, D.C. National Academy Press), 1999, p. 12.

Before World War I, estimating the output of various sectors of the economy—

In 1933 Congress directed the Department of Commerce (DOC) to develop estimates of “total national income for the United States for each of the calendar years 1929, 1930, and 1931, including estimates of the portions of national income originating from [different sectors] and estimates of the distribution of the national income in the form of wages, rents, royalties, dividends, profits and other types of payments.” This directive was the beginning of the NIPA.

In 1934 a small group of economists working under the leadership of Simon Kuznets and in collaboration with the NBER produced a report for the Senate. The report defined many standard economic aggregates still in use today, including gross national product, gross domestic product, consumer spending, and investment spending. Kuznets was later awarded a Nobel Prize for his lifetime of work in this area.

Work continued on the NIPA through World War II, and by 1947 the basic components of the present day income and product accounts were in place. Over the years, the DOC has modified, improved, and updated the data it collects. These data are released on a quarterly basis, with preliminary data being put out in the middle of the month following a given quarter. By the end of a given quarter, the DOC will have collected about two-

The Core of the NIPA

The major components of the NIPA can be found in either of two ways: by adding up the income in the economy or by adding up spending. A simple circular flow diagram of the economy shows why either approach can be used to determine the level of economic activity.

SIMON KUZNETS (1901–1985)

NOBEL PRIZE

Simon Kuznets was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1971 for devising systematic approaches to the compilation and analysis of national economic data. Kuznets is credited with developing gross national product as a measurement of economic output.

Kuznets developed methods for calculating the size and changes in national income known as the national income and product accounts (NIPA). Caring little for abstract models, he sought to define concepts that could be observed empirically and measured statistically. Thanks to Kuznets, economists have had a large amount of data with which to test their economic theories.

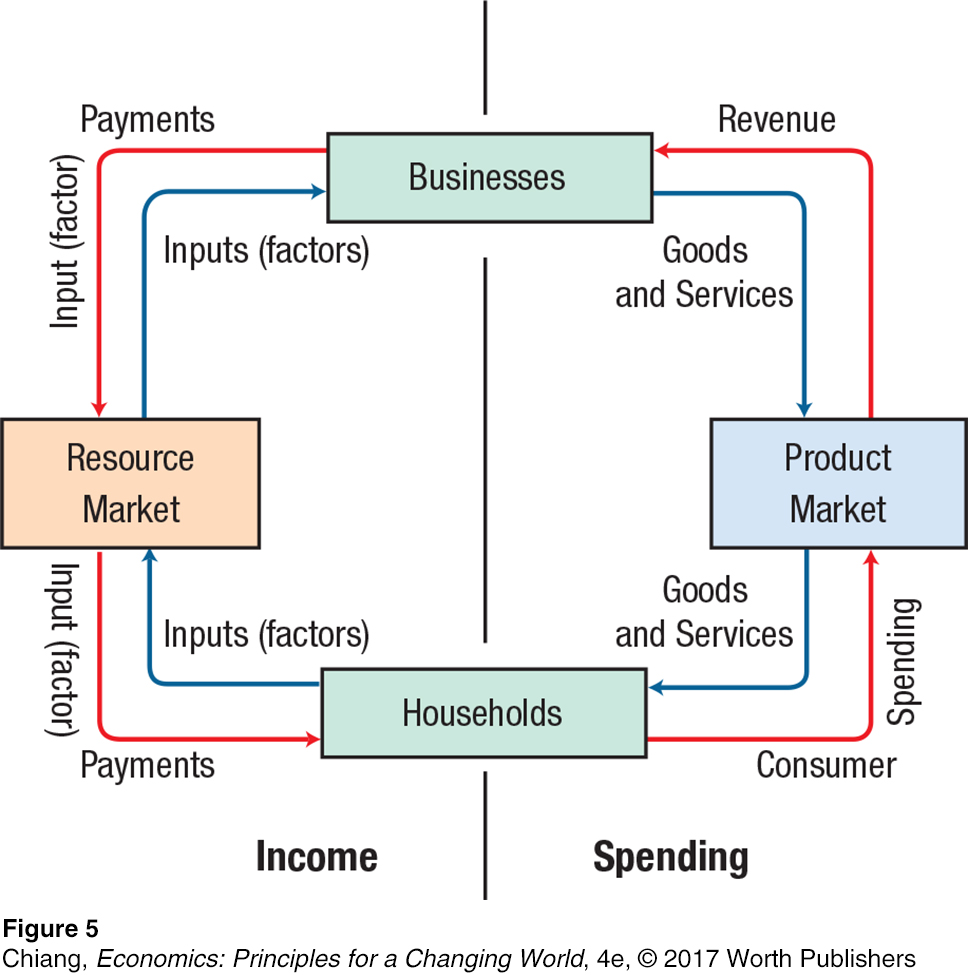

circular flow diagram Illustrates how households and firms interact through product and resource markets and shows that economic aggregates can be determined by examining either spending flows or income flows to households.

The Circular Flow Diagram Figure 5 is a simple circular flow diagram that shows how businesses and households interact through the product and resource markets.

Let us first follow the arrows that point in a clockwise direction. Begin at the bottom of the diagram with households. Households supply labor (and other inputs or factors of production) to the resource market; that is, they become employees of businesses. Businesses use this labor (and other inputs) to produce goods and services that are supplied to the product markets. Such products in the end find their way back into households through consumer purchases. The arrows pointing clockwise show the flow of real items: hours worked, goods and services produced and purchased.

The arrows pointing counterclockwise, in contrast, represent flows of money. Businesses pay for inputs (factors) of production: land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship. Factors are paid rents, wages, interest, and profits. These payments become income for the economy’s households, which use these funds to purchase goods and services in the product market. This spending for goods and services becomes sales revenues for the business sector.

Spending and Income: Looking at GDP in Two Ways The circular flow diagram illustrates why economic aggregates in our economy can be determined in either of two ways. The spending in the economy accrues on the right side of the diagram. In this simple diagram, all spending is assumed to be consumer spending for goods and services. We know, however, that businesses spend money on investment goods such as equipment, plants, factories, and specialized vehicles to increase their productivity. Also, government buys goods and services, as do foreigners. This spending shows up in the NIPA, although it is not included in our simple circular flow diagram.

Second, similar income is generated equal to the spending in the product market. This is shown on the left side of the diagram. Wages and salaries constitute the bulk of income in our economy (roughly two-

The main idea of a circular flow diagram is that every dollar spent in an economy becomes a dollar of income to someone else. For example, suppose you spend $5 on a smoothie, and suppose this $5 goes to the following:

$1 to rent and equipment = income to landlord and equipment makers

$1 to fruits and juices = income to farmers

$1 to wages for store workers and managers = income to labor

$1 to taxes = income to government

$1 to profit = income to investors

Therefore, regardless of whether economic activity is measured by the $5 in spending by the consumer or the $5 in income generated to various parties, the resulting measurement is the same.

Gross Domestic Product

gross domestic product (GDP) A measure of the economy’s total output; it is the most widely reported value in the national income and product accounts (NIPA) and is equal to the total market value of all final goods and services produced by resources in a given year.

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a measure of the economy’s total output; it is the most widely reported value in the NIPA. Technically, the nation’s GDP is equal to the total market value of all final goods and services produced by resources in the United States in a given year. A few points about this definition need to be noted.

First, GDP reflects the final value of goods and services produced. Therefore, measurements of GDP do not include the value of intermediate goods used to produce other products. This distinction helps prevent what economists call “double counting,” because a good’s final value includes the intermediate values going into its production.

To illustrate, consider a box of toothpicks. The firm producing these toothpicks must first purchase a supply of cottonwood, let’s say for $0.22 a box. The firm then mills this wood into toothpicks, which it puts into a small box purchased from another company at $0.08 apiece. The completed box is sold to a grocery store wholesale for $0.65. After a markup, the grocery store sells the box of toothpicks for $0.89. The sale raises GDP by $0.89, not by $1.84 (0.22 + 0.08 + 0.65 + 0.89), because the values of the cottonwood, the box, and the grocery store’s services are already included in the final sales price of a box of toothpicks. Thus, by including only final prices in GDP, double counting is avoided.

A second point to note is that, as the term gross domestic product implies, GDP is a measure of the output produced by resources in the United States. It does not matter whether the producers are American citizens or foreign nationals as long as the production takes place within the country’s borders. GDP does not include goods or services produced abroad, even if the producers are American citizens or companies.

In contrast to GDP is gross national product (GNP), the standard measure of output the Department of Commerce used until the early 1990s. GNP reflects the market value of all goods and services produced domestically and abroad using resources supplied by U.S. citizens, while excluding the value of goods and services produced in the United States by foreign-

Third, whenever possible, the NIPA uses market values, or the prices paid for products, to compute GDP. Therefore, even if a firm must sell its product at a loss, the product’s final sales price is what figures into GDP, not the firm’s production cost or the original retail price.

Fourth, the NIPA accounts focus on market-

The Expenditures (Spending) Approach to Calculating GDP

Again, GDP can be measured using either spending or income. With the expenditures approach, all spending on final goods and services is added together. The four major categories of spending are personal consumption expenditures, gross private domestic investment (GPDI), government spending, and net exports (exports minus imports).

personal consumption expenditures Goods and services purchased by residents of the United States, whether individuals or businesses; they include durable goods, nondurable goods, and services.

Personal Consumption Expenditures Personal consumption expenditures are goods and services purchased by residents and businesses of the United States. Goods and services are divided into three main categories: durable goods, nondurable goods, and services. Durable goods are products that have an average useful life of at least three years. Automobiles, major appliances, books, and musical instruments are all examples of durable goods. Nondurable goods include all other tangible goods, such as canned soft drinks, frozen pizza, toothbrushes, and underwear (all of which should be thrown out before they are three years old). Services are commodities that cannot be stored and are consumed at the time and place of purchase, for example, legal, barber, and repair services. Table 2 gives a detailed account of U.S. personal consumption spending in 2016. Notice that personal consumption is almost 70% of GDP, by far the most important part of GDP, and services constitute the largest portion of personal consumption.

| TABLE 2 | THE EXPENDITURES APPROACH TO GDP (2016) | ||||

| Category | Billions of $ | % of GDP | |||

| Personal Consumption Expenditures | 12,429.0 | 68.5 | |||

| Durable goods | 1,347.6 | 7.4 | |||

| Nondurable goods | 2,663.3 | 14.7 | |||

| Services | 8,418.1 | 46.4 | |||

| Gross Private Domestic Investment | 3,019.2 | 16.7 | |||

| Fixed nonresidential | 2,311.6 | 12.8 | |||

| Fixed residential | 631.8 | 3.5 | |||

| Change in inventories | 75.8 | 0.4 | |||

| Government Purchases of Goods and Services | 3,206.5 | 17.7 | |||

| Federal | 1,235.6 | 6.8 | |||

| State and local | 1,970.9 | 10.9 | |||

| Net Exports | –526.5 | –2.9 | |||

| Exports | 2,214.7 | 12.2 | |||

| Imports | 2,741.2 | 15.1 | |||

| Gross Domestic Product | 18,128.20 | 100.0 | |||

Data from U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, www.bea.gov.

gross private domestic investment (GPDI) Investments in such things as structures (residential and nonresidential), equipment, and software, and changes in private inventories.

Gross Private Domestic Investment The second major aggregate listed in Table 2 is gross private domestic investment (GPDI), which, at 16.7% of GDP, refers to fixed investments, or investments in such things as structures (residential and nonresidential), equipment, and software. It also includes changes in private inventories.

Residential housing represents about one-

A “change in inventories” refers to a change in the physical volume of the inventory a private business owns, valued at the average prices over the period. If a business increases its inventories (whether intentionally or unintentionally due to weak sales volumes), this change is treated as an investment because the business is adding to the stock of products it has ready for sale. This type of investment is generally the least desirable, because excess inventory does not increase productivity and could fall in value if the goods become outdated or if the market price falls.

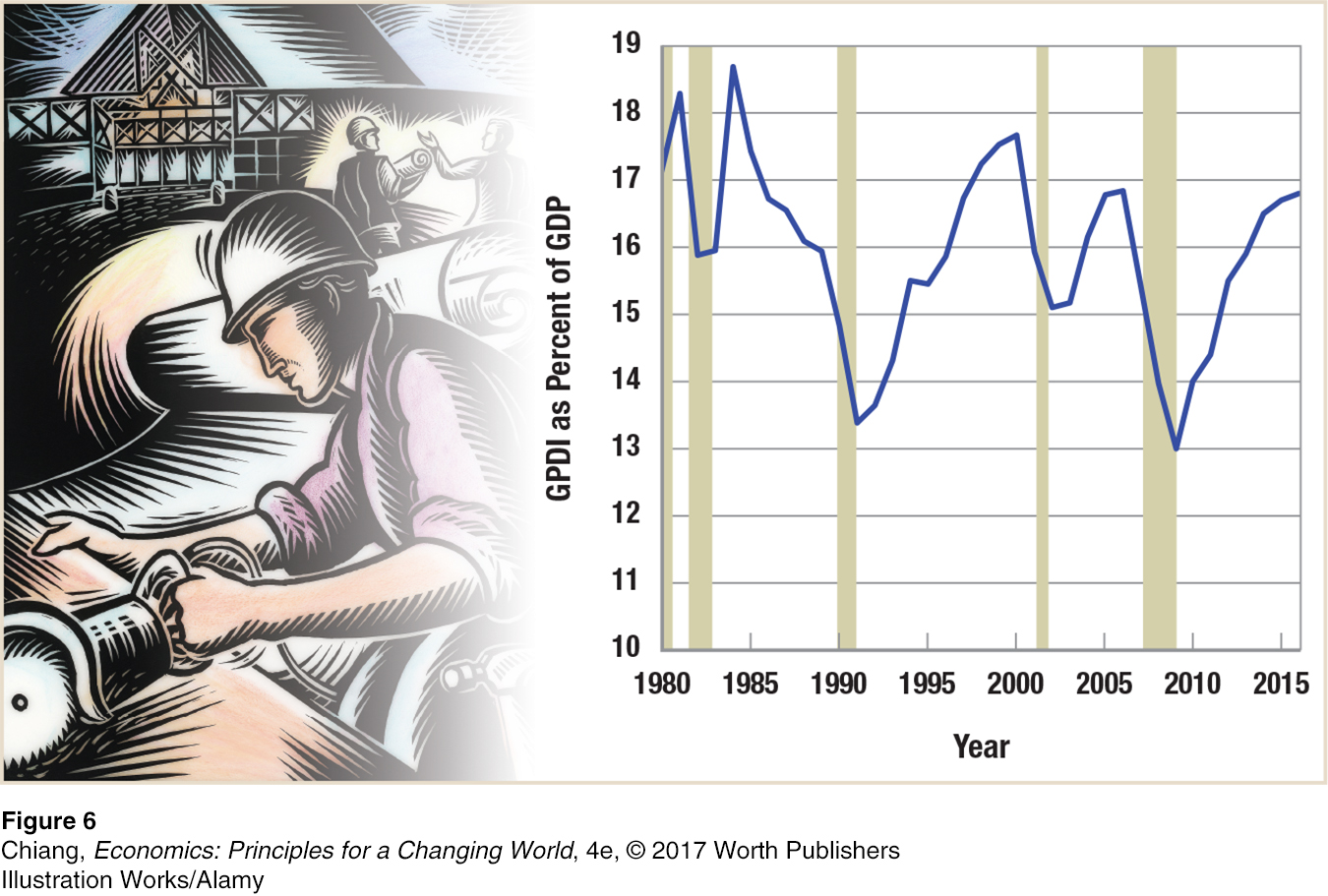

Private investment is a key factor driving economic growth and an important determinant of swings in the business cycle. Figure 6 tracks GPDI as a percentage of GDP since 1980. Recessions are represented by the vertical shaded columns. Notice that during each recession, GPDI turns down, and when the recession ends, GPDI turns up. Investment is, therefore, an important factor shaping the turning points of the business cycle, especially at the troughs, and an important determinant of how severe recessions will be.

government spending Includes the wages and salaries of government employees (federal, state, and local); the purchase of products and services from private businesses and the rest of the world; and government purchases of new structures and equipment.

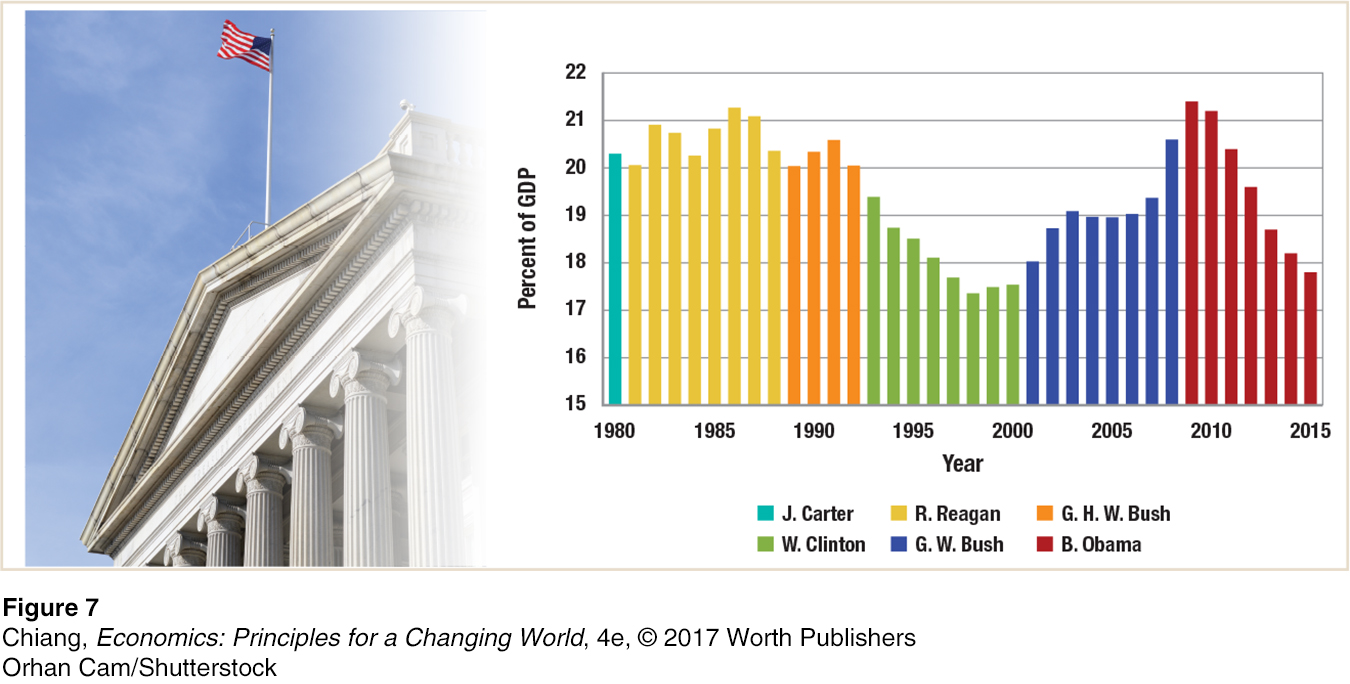

Government Purchases The government component of GDP measures the impact that government spending has on final demand in the economy. As Figure 7 illustrates, at 17.7% of GDP, government spending is a relatively large component of GDP. It includes the wages and salaries of government employees (federal, state, and local) and the purchase of products and services from private businesses and the rest of the world. Government spending also includes the purchase of new structures and equipment.

net exports Exports minus imports for the current period. Exports include all goods and services we sell abroad, while imports include all goods and services we buy from other countries.

Net Exports of Goods and Services Net exports of goods and services are equal to exports minus imports for the current period. Exports include all the items we sell overseas, such as agricultural products, movies, pharmaceutical drugs, and military equipment. Our imports are all those items we bring into the country, including vegetables from Mexico, clothing from India, and cars from Japan. Most years our imports exceed our exports, and therefore net exports are a negative percentage of GDP.

Summing Aggregate Expenditures The four categories just described are commonly abbreviated as C (consumption), I (investment), G (government spending), and X – M (net exports; exports minus imports). Together, these four variables constitute GDP. We summarize this by the following equation:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

Using the information from Table 2, we can calculate GDP for 2016 (in billions of dollars) as

18,128.2 = 12,429.0 + 3,019.2 + 3,206.5 + (–526.5)

The Income Approach to Calculating GDP

As we have already seen, spending that contributes to GDP provides an income for one of the economy’s various inputs (factors) of production. And in theory, this is how this process works. In practice, however, the national income accounts need to be adjusted to fully account for GDP when we switch from the expenditures to the income approach. Let’s work our way through the income side of the NIPA, which Table 3 summarizes.

| TABLE 3 | THE INCOME APPROACH TO GDP (2016) | ||||

| Category | Billions of $ | % of GDP | |||

| Compensation of Employees | 9,852.6 | 54.3 | |||

| Wages and salaries | 7,994.8 | 44.1 | |||

| Supplements to wages and salaries | 1,857.8 | 10.2 | |||

| Proprietors’ Income | 1,412.8 | 7.8 | |||

| Corporate Profits | 1,667.9 | 9.2 | |||

| Rental Income | 670.6 | 3.7 | |||

| Net Interest | 676.8 | 3.8 | |||

| Miscellaneous Adjustments | 1,202.7 | 6.6 | |||

| National Income | 15,483.4 | 85.4 | |||

| Adjustments to National Income | 2,644.8 | 14.6 | |||

| Consumption of fixed capital | 2,856.7 | 15.8 | |||

| Statistical discrepancy | –211.9 | –1.2 | |||

| Gross Domestic Product | 18,128.2 | 100.0 | |||

Data from U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, www.bea.gov.

Compensation of Employees Compensation to employees refers to payments for work done, including wages, salaries, and benefits. Benefits include the social insurance payments made by employers to various government programs, such as Social Security, Medicare, and workers’ compensation and unemployment insurance. Some other benefits that count as labor income are employer-

Proprietors’ Income Proprietors’ income represents the current income of all sole proprietorships, partnerships, and tax-

Corporate Profits Corporate profits are defined as the income that flows to corporations, adjusted for inventory valuation and capital consumption allowances. Most corporations are private enterprises, although this category also includes mutual financial institutions, Federal Reserve banks, and nonprofit institutions that mainly serve businesses. Despite the huge profit figures often reported in the news media, corporate profits are less than 10% of GDP.

Rental Income Rental income, at 3.7% of GDP, is the income that flows to individuals engaged in renting real property (calculated as rent collected less depreciation, property taxes, maintenance and repairs, and mortgage interest). It does not include the income of real estate agents or brokers, but it does include the imputed rental value of homes occupied by their owners (again, less depreciation, taxes, repairs, and mortgage interest), along with royalties from patents, copyrights, and rights to natural resources.

Net Interest Net interest is the interest paid by businesses less the interest they receive, from this country and abroad, and is 3.8% of GDP. Interest expense is the payment for the use of capital. Interest income includes payments from home mortgages, home improvement loans, and home equity loans.

Miscellaneous Adjustments Both indirect business taxes (sales and excise taxes) and foreign income earned in the United States are part of GDP, but must be backed out of payments to factors of production in this country. Neither is paid to U.S. factors of production, and therefore appear in a separate category for measurement purposes.

national income All income, including wages, salaries and benefits, profits (for sole proprietors, partnerships, and corporations), rental income, and interest.

Summing Up Income Measures To this point, we have described different measures of income including wages, salaries, and benefits; profits (for sole proprietors, partnerships, and corporations); rental income; and interest. Summing each of these measures along with the miscellaneous adjustments equals the national income. But be careful—

In order to complete the calculation of GDP using the income approach, two additional measures need to be included. First, an allowance for the depreciation (or consumption) of fixed capital is added. This is the amount of capital or infrastructure that a country needs to undertake in order to maintain its productivity. Second, a small statistical discrepancy is included because like all macroeconomic measurements, it is difficult to be exactly precise, especially in a country as large as the United States. Once these factors are included, GDP is the same whether it is derived from spending or income.

We have now seen how the national income and product accounts determine the major macroeconomic aggregates. But what does the NIPA tell us about the economy? When GDP rises, are we better off as a nation? Do increases in GDP correlate with a rising standard of living? What impact does rising GDP have on the environment and the quality of life? We conclude this chapter with a brief look at some of these questions.

CHECKPOINT

NATIONAL INCOME ACCOUNTING

The circular flow diagram shows how households and firms interact through product and resource markets.

GDP can be computed as spending or as income.

GDP is equal to the total market value of all final goods and services produced by labor and property in an economy in a given year.

Personal consumption expenditures are goods and services purchased by individual and business residents of the United States.

Gross private domestic investment (GPDI) refers to fixed investments such as structures, equipment, and software.

GDP is equal to consumer expenditures, investment expenditures, government purchases, and exports minus imports. In equation form, GDP = C + I + G + (X – M).

GDP can also be computed by adding all of the payments to factors of production. This includes compensation to employees, proprietors’ income, rental income, corporate profits, and net interest, along with some statistical adjustments.

QUESTIONS: Each individual has a sense of how the macroeconomy is doing based on his or her own experience. How might individual experiences lead one astray in thinking about what is happening in the overall economy? How might it help?

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

In general, it is probably a bad idea to interpret how the aggregate economy is doing by using your personal situation. Just because you are having trouble finding a job does not mean that everyone else is. Downsizing by Bank of America and Citigroup in recent years meant that bank workers had problems, even though the rest of the economy may have been growing steadily. There might be times when your situation (such as a layoff in an important industry) may be a leading indicator of what is coming for the economy as a whole. In general, anecdotal evidence is not particularly helpful in forecasting where the aggregate economy is going. When times are uncertain, anecdotal evidence may mislead. Even in recessions, some firms do well; therefore, anecdotal evidence is suspect. This is why the NIPA was created.