GRAMMAR AS RHETORIC AND STYLE Cumulative, Periodic, and Inverted Sentences

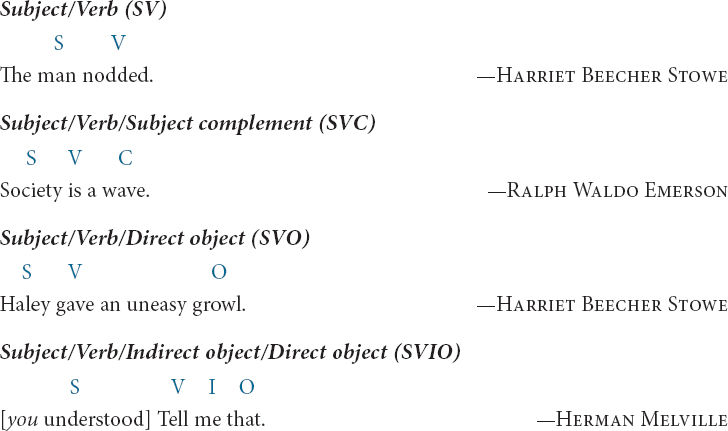

Printed Pages 810-814Most of the time, writers of English use the following standard sentence patterns:

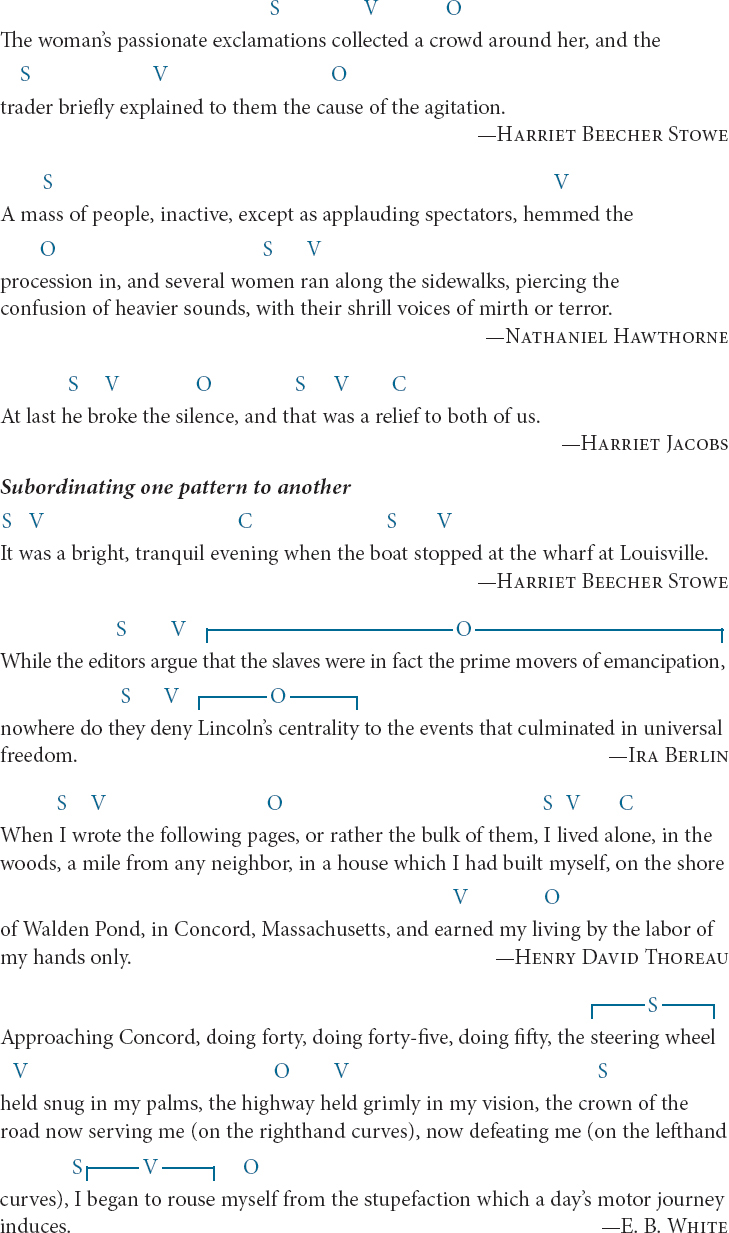

To make longer sentences, writers often coordinate two or more of the standard sentence patterns or subordinate one sentence pattern to another. To make longer sentences, writers often coordinate two or more of the standard sentence patterns using a coordinating conjunction such as and, but, or so, or subordinate one sentence pattern or another. (See the grammar lesson about subordination on p. 336.) Here are examples of both techniques.

Coordinating patterns

One disadvantage of sticking with standard sentence patterns, coordinating them or subordinating them, is that several standard sentences in a row become monotonous. So writers break out of the standard patterns now and then by using a more unusual pattern, such as the cumulative sentence, the periodic sentence, or the inverted sentence. When you use one of these sentence patterns, you call attention to that sentence because its pattern contrasts significantly with those of the sentences surrounding it. You can use unusual sentence patterns to emphasize a point, as well as to control sentence rhythm, increase tension, or create a dramatic impact. In other words, using an unusual pattern helps you avoid monotony in your writing.

Cumulative Sentence

The cumulative, or “loose,” sentence begins with a standard sentence pattern (shown here in blue) and adds multiple details after it. The details can take the form of subordinate clauses or different kinds of phrases. These details accumulate, or pile up—hence, the name cumulative.

He now roamed desperately, and at random, through the town, almost ready to believe that a spell was on him, like that, by which a wizard of his country, had once kept three pursuers wandering, a whole winter night, within twenty paces of the cottage which they sought. —Nathaniel Hawthorne

It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth. —Abraham Lincoln

We ended up on an island along the coast of Florida, in a place by the sea where I leave the doors flung open to the sound of the waves, where early in the morning pelicans flap through the salted fog and dolphins spew their breath beyond the jetty. —Sue Monk Kidd

In the cumulative sentence from Sue Monk Kidd, the independent clause focuses on place, an island in Florida. Then the sentence accumulates a string of modifiers that describe that place with sensory details. Using a cumulative sentence allows Kidd to include all of these modifiers in one smooth sentence rather than use a series of shorter sentences that repeat “island.” Furthermore, this accumulation of modifiers takes the reader into the scene just as the writer experiences it: one detail at a time.

Periodic Sentence

The periodic sentence begins with multiple details and holds off a standard sentence pattern—the subject and predicate (shown here in blue)—until the end.

In the following periodic sentence, Henry David Thoreau begins with several modifiers that detail his thoughts of John Brown. The independent clause comes at the end.

When I think of him, and his six sons, and his son-in-law,—not to enumerate the others,—enlisted for this fight, proceeding coolly, reverently, humanely to work, for months, if not years, sleeping and waking upon it, summering and wintering the thought, without expecting any reward but a good conscience, while almost all America stood ranked on the other side, I say again, that it affects me as a sublime spectacle. —Henry David Thoreau

In the following periodic sentence, Herman Melville packs the front of the sentence with phrases providing elaborate detail. His modifiers describe the circumstances that propel him to “go to sea,” with the independent clause containing the subject and the predicate coming at the end.

Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off—then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can. —Herman Melville

The vivid descriptions and figurative language engage us, so that by the end of the sentence we can feel (or at least imagine) what Ishmael, Melville’s narrator, feels about going to sea. By placing the descriptions at the beginning of the sentence, Melville demonstrates how a series of impressions and circumstances can lead to a decision to act. Could Melville have written this as a cumulative sentence? He probably could have by moving things around—“I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can whenever…”—and then providing the details. The impact of the descriptive detail would be similar in some ways but not exactly the same. Clearly, Melville preferred the periodic to the cumulative in this case.

Whether you choose to place detail at the beginning or the end of a sentence often depends on the surrounding sentences. Unless you have a good reason, though, you probably should not put one cumulative sentence after another or one periodic sentence after another. Instead, by shifting sentence patterns, you can vary sentence length and change the rhythm of your sentences.

Finally, perhaps the most famous example of the periodic sentence in modern English prose is the fourth sentence in paragraph 14 of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” It can be found on page 1345.

Inverted Sentence

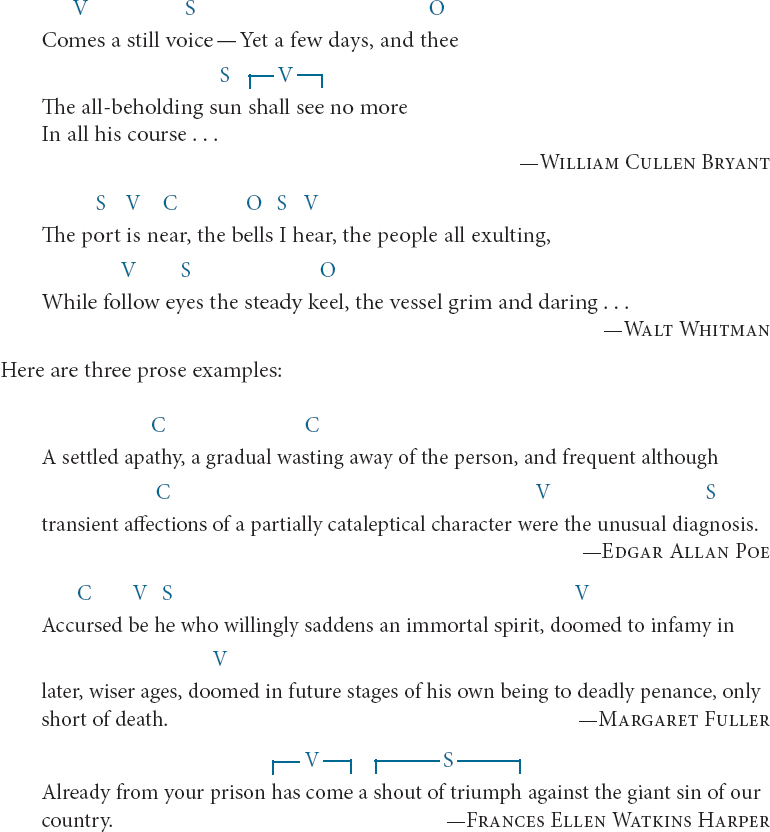

In every standard English sentence pattern, the subject comes before the verb (SV). But if a writer chooses, he or she can invert the standard sentence pattern and put the verb before the subject (VS) or the object before the subject or verb (OVS). This is called an inverted sentence. Inversion is more common in poetry than prose, as the following examples illustrate:

The inverted sentence pattern slows the reader down because it is simply more difficult to comprehend inverted word order. Take this example from Ralph Waldo Emerson.

High be his heart, faithful his will, clear his sight, that he may in good earnest be doctrine, society, law to himself, that a simple purpose may be to him as strong as iron necessity is to others. —Ralph Waldo Emerson

In this example, Emerson calls attention to the adjectives (the subject complements “high, “faithful,” and “clear”) that describe his subject’s condition, placing attention on those features while avoiding beginning with the repetitive “his.” Consider the difference had he written the following:

His heart is high, his will faithful, his sight clear…

This “revised” version is easier to read quickly, and even though the meaning is essentially the same, the emphasis is different. In fact, to understand the full impact, we need to consider the sentence as a whole. The virtues extolled at the beginning (loftiness, faith, and loyalty, clarity of vision) are those necessary for strength of purpose and self-reliance. The emphasis on the virtues that the inversion provides, rather than on the hypothetical man whom they describe, serves Emerson’s purpose.

A Word about Punctuation

It is important to follow the normal rules of comma use when punctuating unusual sentence patterns. In a cumulative sentence, the descriptors that follow the main clause generally need to be set off from it and one another with commas, as in the examples from Hawthorne and Kidd on page 811. Likewise, in a periodic sentence, the series of clauses or phrases that precede the subject should be set off from the subject and one another by commas, as in the example from Thoreau on page 812. When writing an inverted sentence, you may be tempted to insert a comma between the verb and the subject because of the unusual order—but do not the comma insert!