15.3 Antipsychotic Drugs

Milieu therapy and token economy programs helped improve the gloomy outlook for patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, but it was the discovery of antipsychotic drugs in the 1950s that truly revolutionized treatment for schizophrenia. These drugs eliminate many of its symptoms and today are almost always a part of treatment.

antipsychotic drugs Drugs that help correct grossly confused or distorted thinking.

antipsychotic drugs Drugs that help correct grossly confused or distorted thinking.

The discovery of antipsychotic medications dates back to the 1940s, when researchers developed the first antihistamine drugs to combat allergies. The French surgeon Henri Laborit soon discovered that one group of antihistamines, phenothiazines, could also be used to help calm patients about to undergo surgery. After experimenting with several phenothiazine antihistamines and becoming most impressed with one called chlorpromazine, Laborit reported, “It provokes not any loss of consciousness, not any change in the patient’s mentality but a slight tendency to sleep and above all ‘disinterest’ for all that goes on around him.”

BETWEEN THE LINES

Treatment Delay

The average length of time between the first appearance of psychotic symptoms and the initiation of treatment is two years.

(Brunet & Birchwood, 2010)

Laborit suspected that chlorpromazine might also have a calming effect on people with severe psychological disorders. Psychiatrists Jean Delay and Pierre Deniker (1952) tested the drug on six patients with psychotic symptoms and did indeed observe a sharp reduction in their symptoms. In 1954, chlorpromazine was approved for sale in the United States as an antipsychotic drug under the trade name Thorazine (Adams et al., 2014).

Since the discovery of the phenothiazines, other kinds of antipsychotic drugs have been developed. The ones developed throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s are now referred to as “conventional” antipsychotic drugs in order to distinguish them from the “second-

neuroleptic drugs Conventional antipsychotic drugs, so called because they often produce undesired effects similar to the symptoms of neurological disorders.

neuroleptic drugs Conventional antipsychotic drugs, so called because they often produce undesired effects similar to the symptoms of neurological disorders.

How Effective Are Antipsychotic Drugs?

Research has shown that antipsychotic drugs reduce symptoms in at least 65 percent of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia (Advokat et al., 2014; Ellenbroek, 2011; Geddes et al., 2011). Moreover, in direct comparisons the drugs appear to be a more effective treatment for schizophrenia than any of the other approaches used alone, such as psychotherapy, milieu therapy, or electroconvulsive therapy.

For patients helped by the drugs, the medications bring about clear improvement within a period of weeks and maximum improvement within six months (Rabinowitz et al., 2014). However, symptoms may return if the patients stop taking the drugs too soon (Razali et al., 2014; Barnes & Marder, 2011). In one study, when the antipsychotic medications of people with chronic schizophrenia were changed to a placebo after 5 years, 75 percent of the patients relapsed within a year, compared with 33 percent of similar patients who continued to receive medication (Sampath et al., 1992).

As you read in Chapter 14, antipsychotic drugs, particularly the conventional ones, reduce the positive symptoms of schizophrenia (such as hallucinations and delusions) more completely, or at least more quickly, than the negative symptoms (such as restricted affect, poverty of speech, and loss of volition) (Millan, et al., 2014; Stroup et al., 2012). Correspondingly, people whose symptoms are largely positive generally have better rates of recovery from schizophrenia than those with predominantly negative symptoms.

Although antipsychotic drugs are now widely accepted, patients often dislike the powerful effects of the drugs—

The Unwanted Effects of Conventional Antipsychotic Drugs

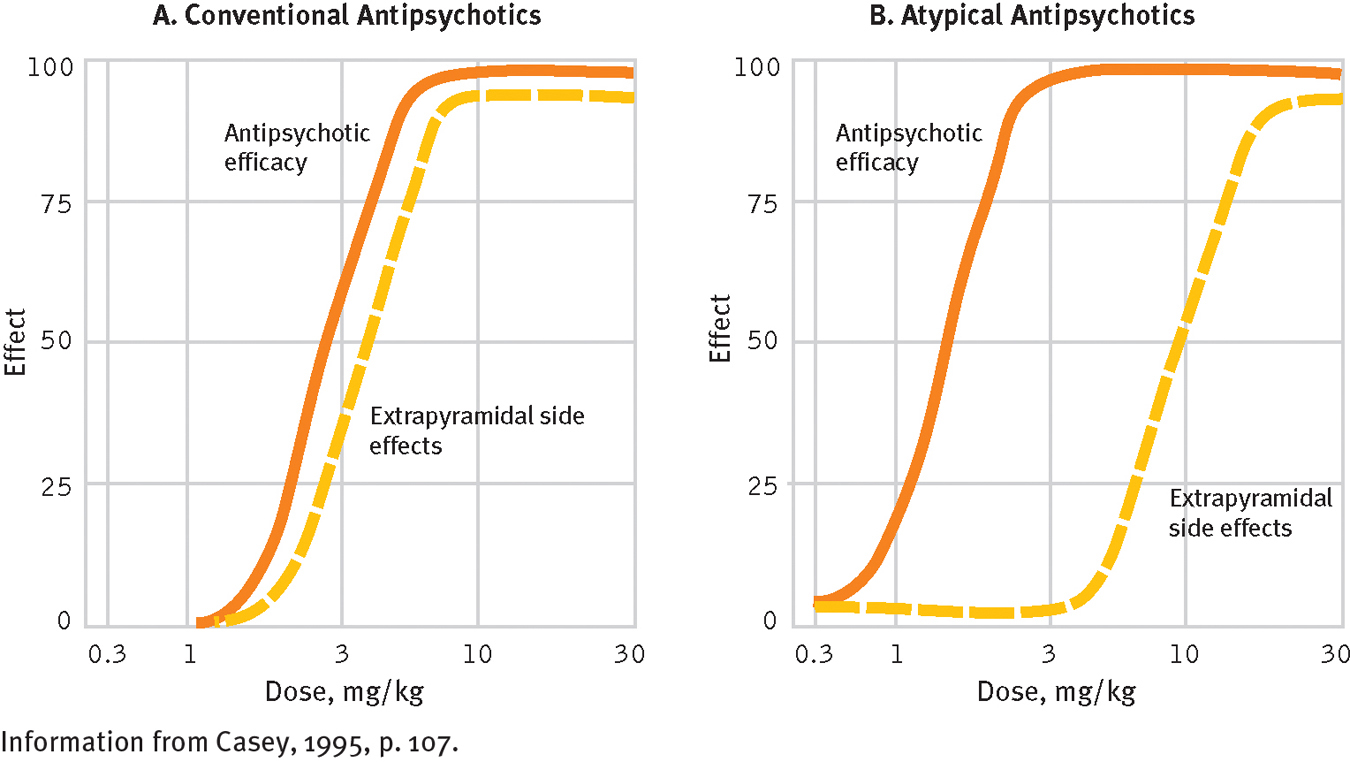

In addition to reducing psychotic symptoms, the conventional antipsychotic drugs sometimes produce disturbing movement problems (Advokat et al., 2014; Stroup et al., 2012). These effects are called extrapyramidal effects because they appear to be caused by the drugs’ impact on the extrapyramidal areas of the brain, areas that help control motor activity. These undesired effects include Parkinsonian and related symptoms, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and tardive dyskinesia.

extrapyramidal effects Unwanted movements, such as severe shaking, bizarre-

extrapyramidal effects Unwanted movements, such as severe shaking, bizarre-

Parkinsonian and Related SymptomsThe most common extrapyramidal effects are Parkinsonian symptoms, reactions that closely resemble the features of the neurological disorder Parkinson’s disease. At least half of patients on conventional antipsychotic drugs have muscle tremors and muscle rigidity at some point in their treatment; they may shake, move slowly, shuffle their feet, and show little facial expression (Geddes et al., 2011; Haddad & Mattay, 2011). Some also have related symptoms such as movements of the face, neck, tongue, and back; and a number experience significant restlessness and discomfort in their limbs, which causes them to move their arms and legs continually in search of relief.

The Parkinsonian and related symptoms seem to be the result of medication-

Neuroleptic Malignant SyndromeIn as many as 1 percent of patients, particularly those who are elderly, conventional antipsychotic drugs produce neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a severe, potentially fatal reaction consisting of muscle rigidity, fever, altered consciousness, and improper functioning of the autonomic nervous system (Haddad & Mattay, 2011). If a person is identified as having the syndrome, he or she is immediately taken off the drug and each neuroleptic symptom is treated medically. In addition, the patient may be given dopamine-

Tardive DyskinesiaWhereas most undesired drug effects appear within days or weeks, a reaction called tardive dyskinesia (meaning “late-

tardive dyskinesia Extrapyramidal effects involving involuntary movements that some patients have after they have taken conventional antipsychotic drugs for an extended time.

tardive dyskinesia Extrapyramidal effects involving involuntary movements that some patients have after they have taken conventional antipsychotic drugs for an extended time.

Most cases of tardive dyskinesia are mild and involve a single symptom, such as tongue flicking; however, some are severe and include such features as continual rocking back and forth, irregular breathing, and grotesque twisting of the face and body. It is believed that more than 10 percent of the people who take conventional antipsychotic drugs for an extended time develop tardive dyskinesia to some degree, and the longer the drugs are taken, the higher the risk becomes (Achalia, 2014; Advokat et al., 2014). Patients over 50 years of age seem to be at greater risk.

Tardive dyskinesia can be difficult, sometimes impossible, to eliminate (Combs et al., 2008). If it is discovered early and the conventional drugs are stopped immediately, it eventually disappears in most cases. Early detection, however, is elusive because some of the symptoms are similar to psychotic symptoms. Clinicians may easily overlook them, continue to administer the drugs, and unintentionally create a more serious case of tardive dyskinesia. Researchers do not fully understand why conventional antipsychotic drugs cause tardive dyskinesia; however, they suspect that, once again, the problem is related to the drugs’ effect on dopamine receptors in the basal ganglia and substantia nigra (Advokat et al., 2014).

Why did psychiatrists in the past keep administering high dosages of antipsychotic drugs to patients who had adverse effects from the medications?

How Should Conventional Antipsychotic Drugs Be Prescribed?Today clinicians are more knowledgeable and more cautious about prescribing conventional antipsychotic drugs than they were in the past (see Table 15-1). Previously, when patients did not improve with such a drug, their clinician would keep increasing the dose; today a clinician will typically add an additional drug to achieve a synergistic effect (called polypharmacy), stop the drug and try an alternative one, or stop all medications (Li et al., 2014; Roh et al., 2014; Leucht, Correll, & Kane, 2011). Today’s clinicians also try to prescribe the lowest effective doses for each patient and to gradually reduce medications weeks or months after the patient begins functioning normally (Barnes & Marder, 2011). Research indicates that, for many such patients, reductions of this kind do not lead to a return of symptoms (Takeuchi et al., 2014). For others, however, only small reductions in dosage are possible, and treatment for these patients typically involves the long-

|

Class/Generic Name |

Trade Name |

|---|---|

|

Conventional antipsychotics |

|

|

Chlorpromazine |

Thorazine |

|

Triflupromazine |

Vesprin |

|

Thioridazine |

Mellaril |

|

Mesoridazine |

Serentil |

|

Trifluoperazine |

Stelazine |

|

Fluphenazine |

Prolixin, Permitil |

|

Perphenazine |

Trilafon |

|

Acetophenazine |

Tindal |

|

Chlorprothixene |

Taractan |

|

Thiothixene |

Navane |

|

Haloperidol |

Haldol |

|

Loxapine |

Loxitane |

|

Molindone hydrochloride |

Moban, Lidone |

|

Pimozide |

Orap |

|

Second- |

|

|

Risperidone |

Risperdal |

|

Clozapine |

Clozaril |

|

Olanzapine |

Zyprexa |

|

Quetiapine |

Seroquel |

|

Ziprasidone |

Geodon |

|

Aripiprazole |

Abilify |

|

Iloperidone |

Fanapt |

|

Lurasidone |

Latuda |

|

Paliperidone |

Invega |

Newer Antipsychotic Drugs

BETWEEN THE LINES

Easy Targets

Adults with schizophrenia are at far greater risk of dying by homicide than other people.

In the United States, more than one-

third of adults with schizophrenia are victims of violent crime. In the United States, adults with schizophrenia are 14 times more likely to be victims of violent crime than to be arrested for committing such a crime.

(Kooyman & Walsh, 2011; Cuvelier, 2002; Hiroeh et al., 2001)

Chapter 14 noted that second-

Second-

The side effect advantage

Conventional antipsychotic drugs are much more likely than second-

Given such advantages, more than half of all medicated patients with schizophrenia now take the second-

Yet the second-

agranulocytosis A life-

agranulocytosis A life-