Chapter Introduction

| CHAPTER |

| 14 |

Schizophrenia

TOPIC OVERVIEW

What Are the Symptoms of Schizophrenia?

What Is the Course of Schizophrenia?

Diagnosing Schizophrenia

Biological Views

Psychological Views

Sociocultural Views

Laura, 40 years old: Laura’s desire was to become independent and leave home … as soon as possible…. She became a professional dancer at the age of 20 … and was booked for … theaters in many European countries….

It was during one of her tours in Germany that Laura met her husband…. They were married and went to live in a small … town in France where the husband’s business was…. She spent a year in that town and was very unhappy…. [Finally] Laura and her husband decided to emigrate to the United States….

They had no children, and Laura … showed interest in pets. She had a dog to whom she was very devoted. The dog became sick and partially paralyzed, and veterinarians felt that there was no hope of recovery…. Finally [her husband] broached the problem to his wife, asking her “Should the dog be destroyed or not?” From that time on Laura became restless, agitated, and depressed….

Later Laura started to complain about the neighbors. A woman who lived on the floor beneath them was knocking on the wall to irritate her. According to the husband, this woman had really knocked on the wall a few times; he had heard the noises. However, Laura became more and more concerned about it. She would wake up in the middle of the night under the impression that she was hearing noises from the apartment downstairs. She would become upset and angry at the neighbors…. Later she became more disturbed. She started to feel that the neighbors were now recording everything she said; maybe they had hidden wires in the apartment. She started to feel “funny” sensations. There were many strange things happening, which she did not know how to explain; people were looking at her in a funny way in the street…. She felt that people were planning to harm either her or her husband…. In the evening when she looked at television, it became obvious to her that the programs referred to her life. Often the people on the programs were just repeating what she had thought. They were stealing her ideas. She wanted to go to the police and report them.

(Arieti, 1974, pp. 165–

Richard, 23 years old: In high school, Richard was an average student. After graduation from high school, he [entered] the army…. Richard remembered [the] period … after his discharge from the army … as one of the worst in his life…. Any, even remote, anticipation of disappointment was able to provoke attacks of anxiety in him…. Approximately two years after his return to civilian life, Richard left his job because he became overwhelmed by these feelings of lack of confidence in himself, and he refused to go look for another one. He stayed home most of the day. His mother would nag him that he was too lazy and unwilling to do anything. He became slower and slower in dressing and undressing and taking care of himself. When he went out of the house, he felt compelled “to give interpretations” to everything he looked at. He did not know what to do outside the house, where to go, where to turn. If he saw a red light at a crossing, he would interpret it as a message that he should not go in that direction. If he saw an arrow, he would follow the arrow interpreting it as a sign sent by God that he should go in that direction. Feeling lost and horrified, he would go home and stay there, afraid to go out because going out meant making decisions or choices that he felt unable to make. He reached the point where he stayed home most of the time. But even at home, he was tortured by his symptoms. He could not act; any motion that he felt like making seemed to him an insurmountable obstacle, because he did not know whether he should make it or not. He was increasingly afraid of doing the wrong thing. Such fears prevented him from dressing, undressing, eating, and so forth. He felt paralyzed and lay motionless in bed. He gradually became worse, was completely motionless, and had to be hospitalized….

Being undecided, he felt blocked, and often would remain mute and motionless, like a statue, even for days.

(Arieti, 1974, pp. 153–

Eventually, Laura and Richard each received a diagnosis of schizophrenia (APA, 2013) (see Table 14-1). People with schizophrenia, though they previously functioned well or at least acceptably, deteriorate into an isolated wilderness of unusual perceptions, odd thoughts, disturbed emotions, and motor abnormalities. In Chapter 15 you will see that schizophrenia is no longer the hopeless disorder of times past and that some sufferers, though certainly not all, now make remarkable recoveries. However, in this chapter let us first take a look at the symptoms of the disorder and at the theories that have been developed to explain them.

schizophrenia A psychotic disorder in which personal, social, and occupational functioning deteriorate as a result of unusual perceptions, odd thoughts, disturbed emotions, and motor abnormalities.

schizophrenia A psychotic disorder in which personal, social, and occupational functioning deteriorate as a result of unusual perceptions, odd thoughts, disturbed emotions, and motor abnormalities.

|

Schizophrenia |

|

|---|---|

|

1. |

For 1 month, individual displays two or more of the following symptoms much of the time: |

|

|

(a) Delusions |

|

|

(b) Hallucinations |

|

|

(c) Disorganized speech |

|

|

(d) Very abnormal motor activity, including catatonia |

|

|

(e) Negative symptoms |

|

2. |

At least one of the individual’s symptoms must be delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech. |

|

3. |

Individual functions much more poorly in various life spheres than was the case prior to the symptoms. |

|

4. |

Beyond this 1 month of intense symptomology, individual continues to display some degree of impaired functioning for at least 5 additional months. |

|

(Information from: APA, 2013.) |

|

Like Laura and Richard, people with schizophrenia experience psychosis, a loss of contact with reality. Their ability to perceive and respond to the environment becomes so disturbed that they may not be able to function at home, with friends, in school, or at work (Harvey, 2014). They may have hallucinations (false sensory perceptions) or delusions (false beliefs), or they may withdraw into a private world. As you saw in Chapter 12, taking LSD or abusing amphetamines or cocaine may produce psychosis (see PsychWatch on page 468). So may injuries or diseases of the brain. And so may other severe psychological disorders, such as major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder (Pearlson & Ford, 2014). Most commonly, however, psychosis appears in the form of schizophrenia. The term schizophrenia comes from the Greek words for “split mind.”

psychosis A state in which a person loses contact with reality in key ways.

psychosis A state in which a person loses contact with reality in key ways.

Actually, there are a number of schizophrenia-

|

Disorder |

Key Features |

Duration |

Lifetime Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Schizophrenia |

Various psychotic symptoms, such as delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, restricted or inappropriate affect, and catatonia |

6 months or more |

1.0% |

|

Brief psychotic disorder |

Various psychotic symptoms, such as delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, restricted or inappropriate affect, and catatonia |

Less than 1 month |

Unknown |

|

Schizophreniform disorder |

Various psychotic symptoms, such as delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, restricted or inappropriate affect, and catatonia |

1 to 6 months |

0.2% |

|

Schizoaffective disorder |

Marked symptoms of both schizophrenia and a major depressive episode or a manic episode |

6 months or more |

Unknown |

|

Delusional disorder |

Persistent delusions that are not bizarre and not due to schizophrenia; persecutory, jealous, grandiose, and somatic delusions are common |

1 month or more |

0.1% |

|

Psychotic disorder due to another medical condition |

Hallucinations, delusions, or disorganized speech caused by a medical illness or brain damage |

No minimum length |

Unknown |

|

Substance/medication- |

Hallucinations, delusions, or disorganized speech caused directly by a substance, such as an abused drug |

No minimum length |

Unknown |

|

(Information from: APA, 2013.) |

|||

Approximately 1 of every 100 people in the world suffers from schizophrenia during his or her lifetime (Long et al., 2014; Lindenmayer & Khan, 2012). An estimated 24 million people worldwide are afflicted with it, including 2.5 million in the United States (NIMH, 2010). Its financial cost is enormous, and the emotional cost is even greater (Feldman et al., 2014; Kennedy et al., 2014). In addition, people with schizophrenia have an increased risk of physical—

As you read in Chapter 9, people with schizophrenia also are much more likely to attempt suicide than the general population. It is estimated that as many as 25 percent of people with schizophrenia attempt suicide (Kasckow et al., 2011; Meltzer, 2011). Given this high risk, it is now strongly recommended that patients with schizophrenia receive thorough suicide risk assessments during treatment and when they are discharged from treatment programs (Pedersen et al., 2014).

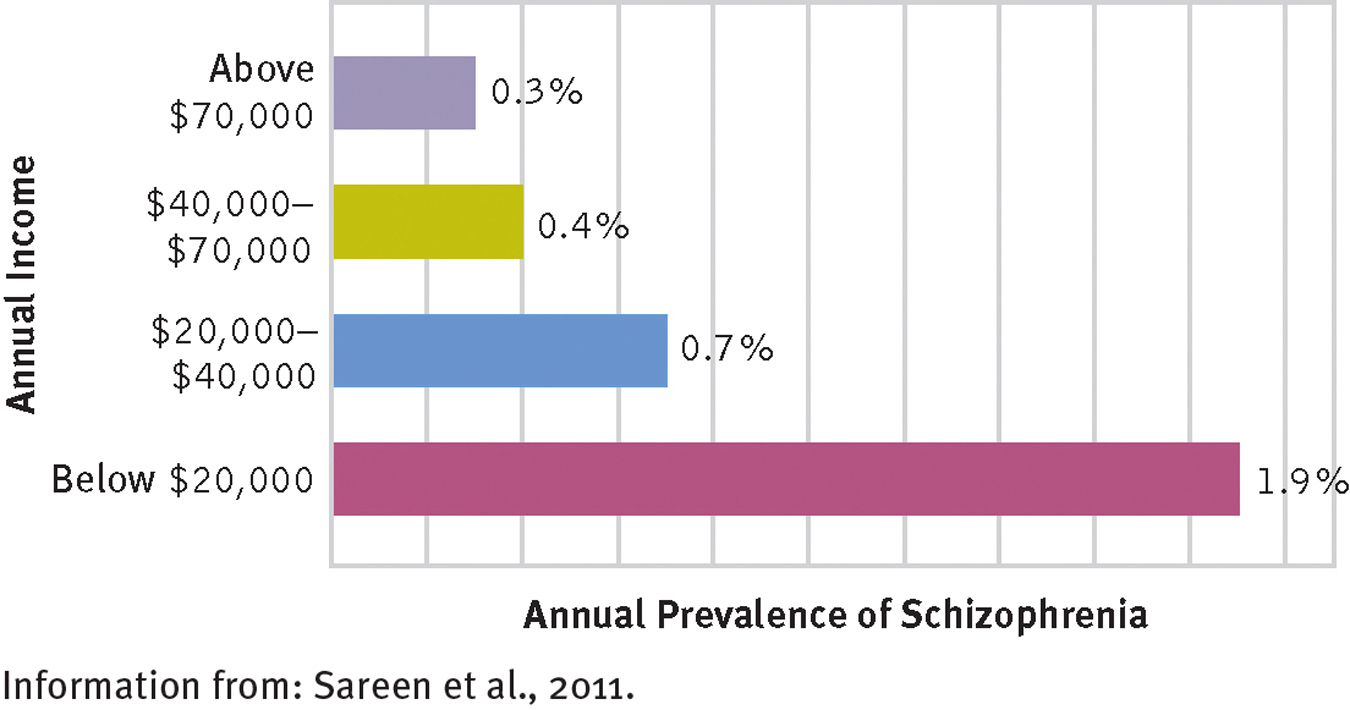

Although schizophrenia appears in all socioeconomic groups, it is found more frequently in the lower levels (Burns, Tomita, & Kapadia, 2014; Sareen et al., 2011) (see Figure 14-1). This has led some theorists to believe that the stress of poverty is itself a cause of the disorder. However, it could be that schizophrenia causes its sufferers to fall from a higher to a lower socioeconomic level or to remain poor because they are unable to function effectively (Jablensky, Kirkbride, & Jones, 2011). This is sometimes called the downward drift theory.

Socioeconomic class and schizophrenia

Poor people in the United States are more likely than wealthy people to experience schizophrenia.

Equal numbers of men and women are diagnosed with schizophrenia. The average age of onset for men is 23 years, compared with 28 years for women (Lindenmayer & Khan, 2012). Almost 3 percent of all those who are divorced or separated suffer from schizophrenia sometime during their lives, compared with 1 percent of married people and 2 percent of people who remain single. Again, however, it is not clear whether marital problems are a cause or a result (Solter et al., 2004; Keith et al., 1991).

People have long shown great interest in schizophrenia, flocking to plays and movies that explore or exploit our fascination with the disorder. Yet, as you will read, all too many people with schizophrenia are neglected in our country, their needs almost entirely ignored. Although effective interventions have been developed, sufferers live without adequate treatment and never fully fulfilling their potential as human beings.