15.4 Psychotherapy

Before the discovery of antipsychotic drugs, psychotherapy was not really an option for people with schizophrenia. Most were too far removed from reality to profit from it. Only a handful of therapists, apparently blessed with extraordinary patience and skill, specialized in the psychotherapeutic treatment of this disorder and reported a measure of success (Will, 1967, 1961; Sullivan, 1962, 1953; Fromm-Reichmann, 1950, 1948, 1943). These therapists believed that the first task of such therapy was to win the trust of patients with schizophrenia and build a close relationship with them.

"And only you can hear this whistle?"

Well-known clinical theorist and therapist Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, for example, would initially tell her patients that they could continue to exclude her from their private world and hold onto their disorder as long as they wished. She reported that eventually, after much testing and acting out, the patients would accept, trust, and grow attached to her and begin to talk to her about their problems. Case studies seemed to attest to the effectiveness of such approaches and to the importance of trust and emotional bonding in treatment. Here a recovered woman tells her therapist how she had felt during their early interactions:

At the start, I didn’t listen to what you said most of the time but I watched like a hawk for your expression and the sound of your voice. After the interview, I would add all this up to see if it seemed to show love. The words were nothing compared to the feelings you showed. I sense that you felt confident I could be helped and that there was hope for the future….

The problem with schizophrenics is that they can’t trust anyone. They can’t put their eggs in one basket. The doctor will usually have to fight to get in no matter how much the patient objects….

Loving is impossible at first because it turns you into a helpless little baby. The patient can’t feel safe to do this until he is absolutely sure the doctor understands what is needed and will provide it.

Today, psychotherapy is successful in many more cases of schizophrenia (Miller et al., 2012; Swartz et al., 2012). By helping to relieve thought and perceptual disturbances, antipsychotic drugs allow people with schizophrenia to learn about their disorder, participate actively in therapy (see MindTech below), think more clearly about themselves and their relationships, make changes in their behavior, and cope with stressors in their lives. The most helpful forms of psychotherapy include cognitive-behavioral therapy and two sociocultural interventions—family therapy and social therapy. Often the various approaches are combined.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

As you read in Chapter 14, the cognitive explanation for schizophrenia starts with the premise that people with the disorder do indeed actually hear voices (or experience other kinds of hallucinations) as a result of biologically triggered sensations. According to this theory, the journey into schizophrenia takes shape when people try to make sense of these strange sensations and conclude incorrectly that the voices are coming from external sources, that they are being persecuted, or another such notion. These misinterpretations are essentially delusions.

Page 506

MindTech

Putting a Face on Auditory Hallucinations

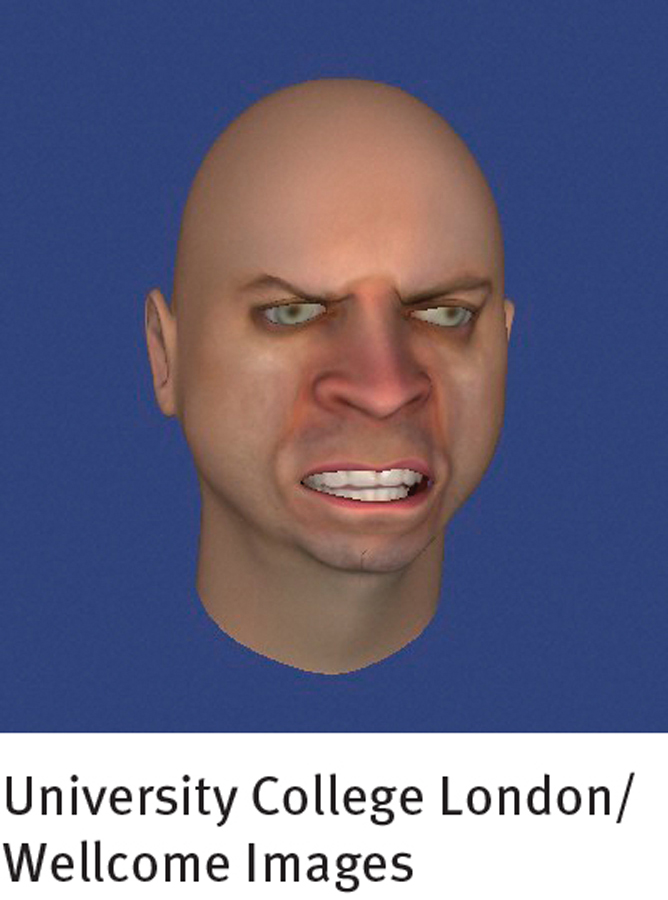

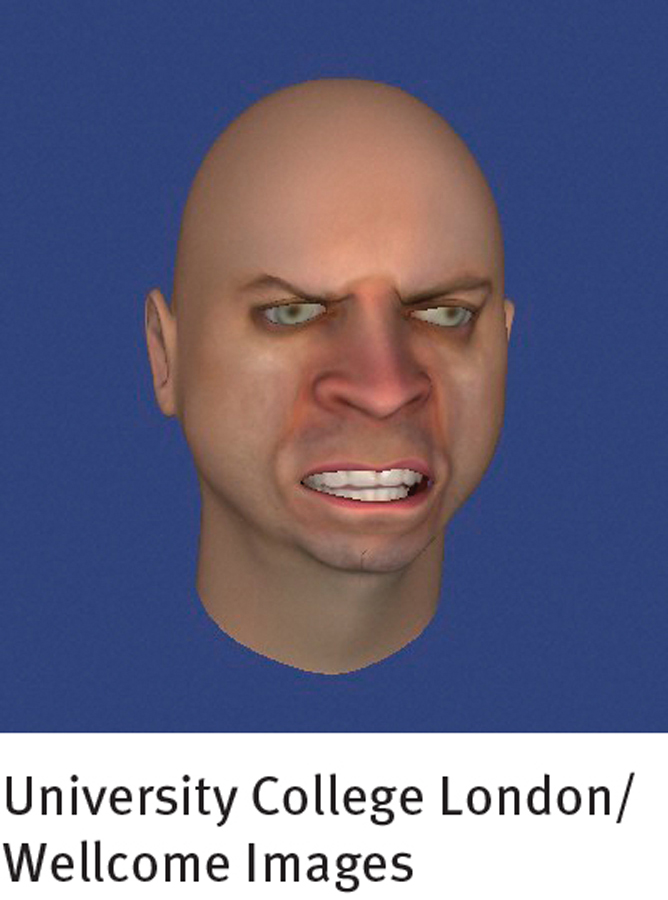

In Chapter 3, you read that a growing number of therapists are using avatar therapy to help clients overcome their psychological problems. In this form of cybertherapy, therapists have the clients interact with computer-generated on-screen virtual human figures. Perhaps the boldest application of avatar therapy is its use with schizophrenic patients. Clinical researcher Julian Leff and several colleagues have developed an approach that seems to offer particular promise for such people (Leff et al., 2013).

Voices spring to virtual life This is one of the sinister-looking avatars developed by clinical researcher Julian Leff and his colleagues in their new treatment for people with schizophrenia.

For a pilot study, the researchers selected 16 participants who were being tormented by imaginary voices (auditory hallucinations). In each case, the therapist presented the patient with a mean-sounding and mean-looking avatar. The avatar’s voice pitch and appearance were designed based on the patient’s description of what he was hearing and what he believed would be a corresponding face.

The patient was placed alone in a room with the computer simulation while the therapist generated the on-screen avatar from another room. Initially, the avatar spewed all sorts of frightening and upsetting statements at the patient. Then, the therapist encouraged the patient to fight back—to tell the avatar things such as “I will not put up with this, what you are saying is nonsense, I don’t believe these things, you must go away and leave me alone, and I do not need this kind of torment” (Kedmey, 2014; Leff et al., 2013).

After seven 30-minute sessions, most of the participants in the pilot study had less frequent and less intense auditory hallucinations and reported being less upset by the voices they did continue to hear. The participants also reported improvements in their feelings of depression and suicidal thinking. Three of the 16 actually reported a total cessation of their auditory hallucinations after the sessions. These promising results are now being followed up in a larger study with more participants. The results of that study should clarify whether confronting one’s hallucinations in a virtual world can truly help people with schizophrenia.

Can you think of any negative effects—short-term or long-term—that might result from putting a face on auditory hallucinations?

With this explanation in mind, an increasing number of clinicians now employ a cognitive-behavioral treatment for schizophrenia that is designed to help change how people view and react to their hallucinations (Howes & Murray, 2014; Hagen et al., 2011; Dudley & Turkington, 2011). The therapists believe that if people can be guided to interpret such experiences in a more accurate way, they will not suffer the fear and confusion produced by their delusional misinterpretations (Naeem et al., 2014). Thus, the therapists use a combination of behavioral and cognitive techniques:

BETWEEN THE LINES

“I feel cheated by having this illness.”

Person with schizophrenia, 1996

They provide clients with education and evidence about the biological causes of hallucinations.

They help clients learn more about the “comings and goings” of their own hallucinations and delusions. The clients learn, for example, to identify which kinds of events and situations trigger the voices in their heads.

Page 507

The therapists challenge their clients’ inaccurate ideas about the power of their hallucinations, such as the idea that the voices are all-powerful and uncontrollable and must be obeyed. The therapists also have the clients conduct behavioral experiments to put such notions to the test. What happens, for example, if the clients occasionally resist following the orders from their hallucinatory voices?

The therapists teach clients to reattribute and more accurately interpret their hallucinations. Clients may, for example, adopt and apply alternative conclusions such as “It’s not a real voice, it’s my illness.”

The therapists teach clients techniques for coping with their unpleasant sensations (hallucinations). The clients may, for example, learn ways to reduce the physical arousal that accompanies hallucinations—using special breathing and relaxation techniques, positive self-statements, and the like. Similarly, they may learn to refocus or distract themselves whenever the hallucinations occur. In one reported case, a therapist repeatedly walked behind his schizophrenic client and made harsh and critical statements, seeking to simulate the clients’ auditory hallucinations and then guiding him to focus his attention past the voices and on to the task at hand (Veiga-Martínez et al., 2008).

BETWEEN THE LINES

“What’s so great about reality?”

Person with schizophrenia, 1988

These behavioral and cognitive techniques often help schizophrenic people feel more control over their hallucinations and reduce their delusional ideas. But they do not eliminate the hallucinations. They simply render the hallucinations less powerful and less destructive. Can anything be done further to lessen the hallucinations’ unpleasant impact on the person? Yes, say new-wave cognitive-behavioral therapists, including practitioners of acceptance and commitment therapy.

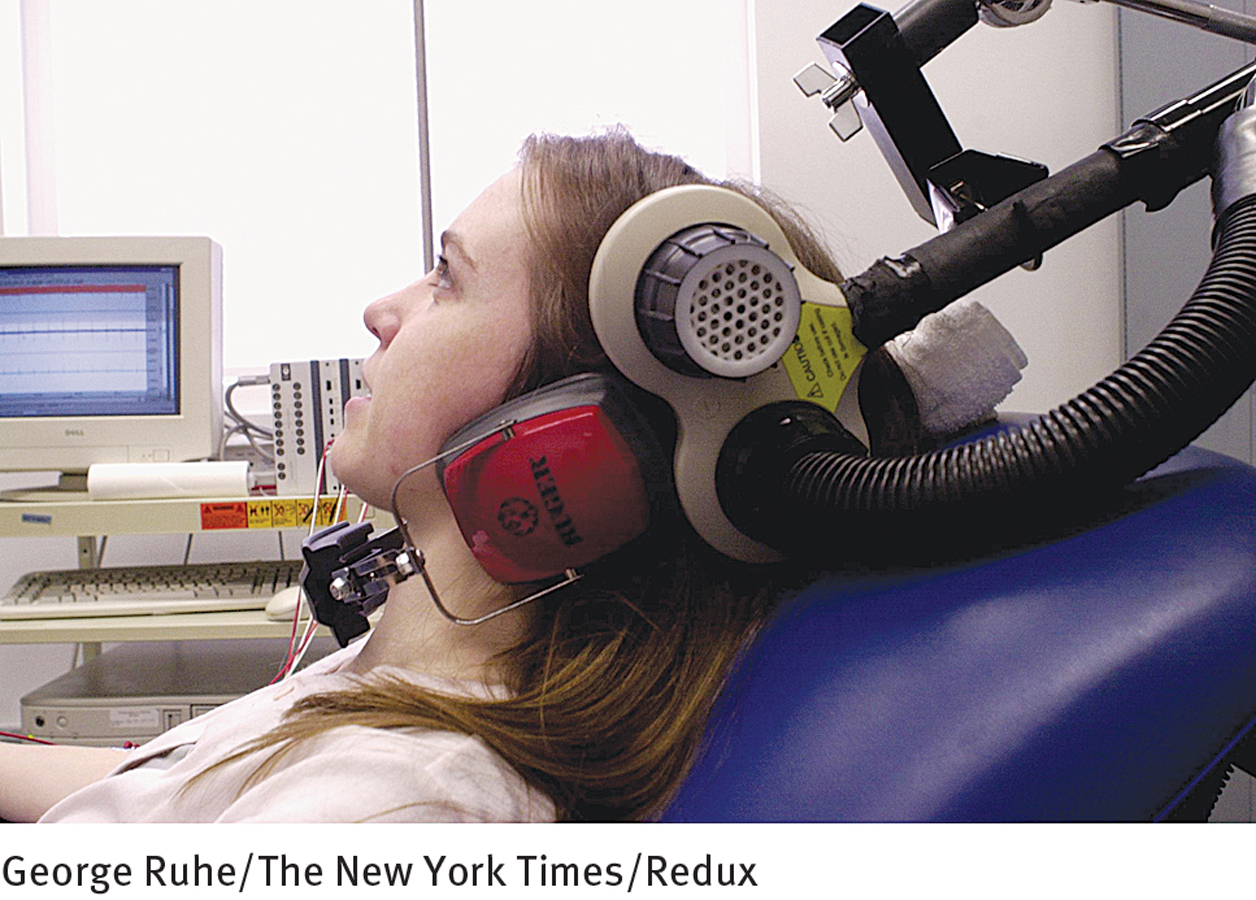

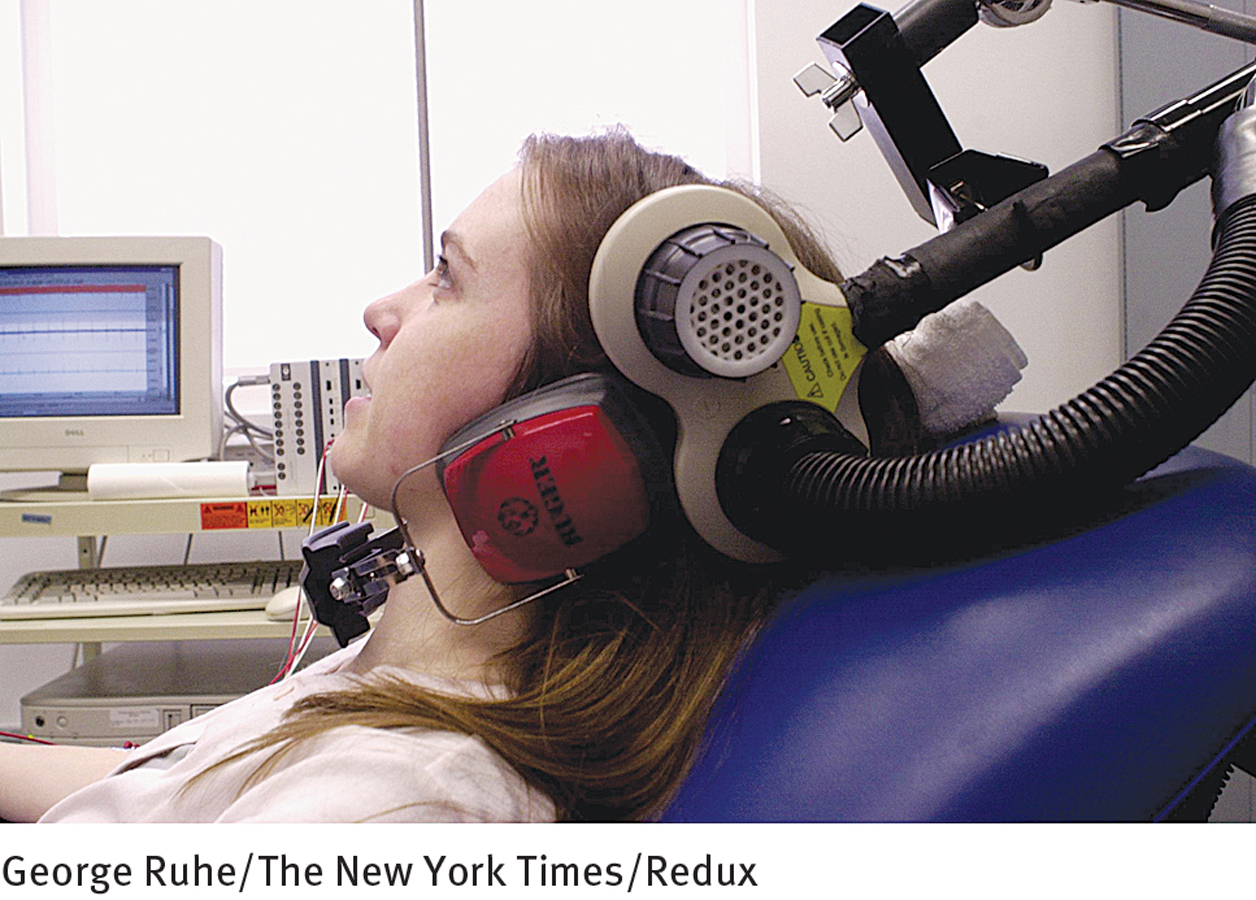

Reducing auditory sensations While cognitive-behavioral therapists try to help people with schizophrenia more accurately interpret their hallucinations, biological researchers keep trying to rid sufferers of the sensations that produce the hallucinations. Researcher Ralph Hoffman and his colleagues, for example, have used a transcranial magnetic stimulation procedure to reduce neural excitability in the auditory brain centers of patients with schizophrenia. The procedure, demonstrated here by one of the researchers, has reduced the hallucinations of many patients (Hoffman, 2010; Hoffman et al., 2007, 2000).

As you read in Chapters 3 and 5, new-wave cognitive-behavioral therapists believe that the most useful goal of treatment is often to help clients accept their streams of problematic thoughts rather than to judge them, act on them, or try fruitlessly to change them (Hayes & Lillis, 2012; Hayes et al., 2004; Hayes, 2002). The therapists, for example, help highly anxious individuals to become simply mindful of the worries that engulf their thinking and to accept such negative thoughts as but harmless events of the mind (see pages 138–139). Similarly, in cases of schizophrenia, new-wave cognitive-behavioral therapists try to help clients become detached and comfortable observers of their hallucinations—merely mindful of the unusual sensations and accepting of them—while otherwise moving forward with the tasks and events of their lives (Chien et al., 2014; Bach, 2007).

Studies indicate that these various cognitive-behavioral treatments are often very helpful to clients with schizophrenia (Briki et al., 2014; Morrison et al., 2014; Swartz et al., 2012). Many clients who receive such treatments report that they feel less distressed by their hallucinations and that they have fewer delusions. Indeed, they are often able to shed the diagnosis of schizophrenia. Rehospitalizations decrease by 50 percent among clients treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy.

The cognitive-behavioral view that hallucinations should be accepted (rather than misinterpreted or overreacted to) is compatible with a notion already held by some people who hallucinate. There are a number of self-help groups comprised of people with auditory hallucinations whose guiding principles are that hallucinations themselves are harmless and valid experiences and that those who have auditory hallucinations often do best if they simply can accept and learn to live with them.

Page 508

Family Therapy

More than 50 percent of those who are recovering from schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders live with their families: parents, siblings, spouses, or children (Tsai et al., 2011; Barrowclough & Lobban, 2008). Such situations create special pressures; even if family stress was not a factor in the onset of the disorder, a patient’s recovery may be strongly influenced by the behavior and reactions of his or her relatives at home (Macleod et al., 2011).

Generally speaking, people with schizophrenia who feel positive toward their relatives do better in treatment (Okpokoro et al., 2014). As you saw in Chapter 14, recovered patients living with relatives who display high levels of expressed emotion—that is, relatives who are very critical, emotionally overinvolved, and hostile—often have a much higher relapse rate than those living with more positive and supportive relatives. Moreover, for their part, family members may be very upset by the social withdrawal and unusual behaviors of a relative with schizophrenia (Friedrich et al., 2014; Quah, 2014).

To address such issues, clinicians now commonly include family therapy in their treatment of schizophrenia, providing family members with guidance, training, practical advice, psychoeducation about the disorder, and emotional support and empathy (Burbach, Fadden, & Smith, 2010). In family therapy, relatives develop more realistic expectations and become more tolerant, less guilt-ridden, and more willing to try new patterns of communication. Family therapy also helps the person with schizophrenia cope with the pressures of family life, make better use of family members, and avoid troublesome interactions.

Research has found that family therapy—particularly when it is combined with drug therapy—helps reduce tensions within the family and so helps relapse rates go down (Okpokoro et al., 2014; Swartz et al., 2012; Haddock & Spaulding, 2011). The principles of this approach are evident in the following description:

Spontaneous improvement? For reasons unknown, the symptoms of some people with schizophrenia lessen during old age, even without treatment (Meeks & Jeste, 2008; Fisher et al., 2001). An example is the remarkable late-life improvement of John Nash, the subject of the book and movie A Beautiful Mind. Nash, seen here giving a presentation in 2010, received the 1994 Nobel Prize in Economic Science after struggling with schizophrenia for 35 years.

Mark was a 32-year-old single man living with his parents. He had a long and stormy history of schizophrenia with many episodes of psychosis, interspersed with occasional brief periods of good functioning. Mark’s father was a bright but neurotically tormented man gripped by obsessions and inhibitions. Mark’s mother appeared weary, detached, and embittered. Both parents felt hopeless about Mark’s chances of recovery and resentful that needing to care for him would always plague their lives. They acted as if they were being intentionally punished. It gradually emerged that the father, in fact, was riddled with guilt and self-doubt; he suspected that his wife had been cold and rejecting toward Mark as an infant and that he had failed to intervene, due to his unwillingness to confront his wife and the demands of graduate school that distanced him from home life. He entertained the fantasy that Mark’s illness was a punishment for this. Every time Mark did begin to show improvement—both in reduced symptoms and in increased functioning—his parents responded as if it were just a cruel torment designed to raise their hopes and then to plunge them into deeper despair when Mark’s condition deteriorated. This pattern was especially apparent when Mark got a job. As a result, at such times, the parents actually became more critical and hostile toward Mark. He would become increasingly defensive and insecure, finally developing paranoid delusions, and usually would be hospitalized in a panicky and agitated state.

All of this became apparent during the psychoeducational sessions. When the pattern was pointed out to the family, they were able to recognize their self-fulfilling prophecy and were motivated to deal with it. As a result, the therapist decided to see the family together. Concrete instances of the pattern and its consequences were explored, and alternative responses by the parents were developed. The therapist encouraged both the parents and Mark to discuss their anxieties and doubts about Mark’s progress, rather than to stir up one another’s expectations of failure. The therapist had regular individual sessions with Mark as well as the family sessions. As a result, Mark has successfully held a job for an unprecedented 12 months.

(Heinrichs & Carpenter, 1983, pp. 284–285)

Page 509

BETWEEN THE LINES

“Her face was a solemn mask, and she could neither give nor receive affection.”

Mother, 1991, describing her daughter who has schizophrenia

The families of people with schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders may also turn to family support groups and family psychoeducational programs for encouragement and advice (Fallahi Khoshknab et al., 2014; McFarlane, 2011). In such programs, family members meet with others in the same situation to share their thoughts and emotions, provide mutual support, and learn about schizophrenia. Although research has yet to fully determine the usefulness of these groups, the approach has become popular.

Social Therapy

Many clinicians believe that the treatment of people with schizophrenia should include techniques that address social and personal difficulties in the clients’ lives. These clinicians offer practical advice; work with clients on problem solving, memory enhancement, decision making, and social skills; make sure that the clients are taking their medications properly; and may even help them find work, financial assistance, appropriate health care, and proper housing (Granholm et al., 2014; Ordemann et al., 2014; Ridgway, 2008).

Research finds that this practical, active, and broad approach, called social therapy or personal therapy, does indeed help keep people out of the hospital (Haddock & Spaulding, 2011; Hogarty, 2002). One study compared the progress of four groups of patients with chronic schizophrenia after their discharge from a state hospital (Hogarty et al., 2006, 1986, 1974). One group received both antipsychotic medications and social therapy in the community, while the other groups received medication only, social therapy only, or no treatment of any kind. The researchers’ first finding was that chronic patients need to continue taking medication after being released in order to avoid rehospitalization. Over a two-year period, 80 percent of those who did not continue medication needed to be hospitalized again, compared with 48 percent of those who received medication. They also found that among the patients on medication, those who also received social therapy adjusted to the community and avoided rehospitalization most successfully. Other studies tell a similar story (Razali et al., 2014). Clearly, social therapy played an important role in their recovery.

![]()