16.1 “Odd” Personality Disorders

The cluster of “odd” personality disorders consists of the paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders. People with these disorders typically have odd or eccentric behaviors that are similar to but not as extensive as those seen in schizophrenia, including extreme suspiciousness, social withdrawal, and peculiar ways of thinking and perceiving things. Such behaviors often leave the person isolated. Some clinicians believe that these personality disorders are related to schizophrenia. In fact, schizotypal personality disorder is listed twice in DSM-

Clinicians have learned much about the symptoms of the odd cluster personality disorders but have not been so successful in determining their causes or how to treat them. In fact, as you’ll soon see, people with these disorders rarely seek treatment.

Paranoid Personality Disorder

As you read earlier, people with paranoid personality disorder deeply distrust other people and are suspicious of their motives (APA, 2013). Because they believe that everyone intends them harm, they shun close relationships. Their trust in their own ideas and abilities can be excessive, though, as you can see in the case of Eduardo:

paranoid personality disorder A personality disorder marked by a pattern of distrust and suspiciousness of others.

paranoid personality disorder A personality disorder marked by a pattern of distrust and suspiciousness of others.

For Eduardo, a researcher at a genetic engineering research company, this was the last straw. He had been severely chastised by his supervisor for disregarding company protocol and deviating from the research procedure on a major study. He knew where this was coming from. He had been “ratted out” by his jealous, conniving lab colleagues—

At the outset of the meeting, Eduardo insisted that he would not leave the room until he was told the name of the person who had ratted him out. He acknowledged that he had, in fact, altered the study’s research design in key ways—

Eduardo quickly shifted the focus of the meeting onto his lab colleagues. He stated that the other scientists were intimidated by his visionary ideas, and he accused them of trying to get him out of the way so they could continue to work in an unproductive, low-

The other researchers were aghast as Eduardo laid out his suspicions. They knew he didn’t like them, but they had not, until now, recognized the depth of his fury or the number of his imagined slights. One of them, Xavier, spoke up. First, they had no idea that he was unilaterally changing the research protocol, so of course there was no way that they could have reported his actions to the super visor. Second, and more generally, it was he, not they, who was always behaving in an unfriendly and back-

Next, Eduardo’s supervisor, Lisa, spoke up. She said that in her objective opinion, none of Eduardo’s accusations were true. First, none of his colleagues had informed on him, because he had conducted his modified protocols after they had gone home. She had reviewed videos from the lab cameras as a matter of routine and had noticed him feeding rats that were supposed to be hungry later. While acknowledging that his research ideas were interesting, she pointed out that his unilateral changes in procedure were throwing off the validity of the study. Lisa reminded him that any deviation would have had to be approved by her and that she would not be able to give that approval without submitting a written request to their financial backers.

Second, she said that in her observations of everyday lab interactions, it was Xavier’s account that rang true, not Eduardo’s. She even added a few points of her own—

Later, in the privacy of her office, Lisa told Eduardo that she had no choice but to let him go. She said that his behavior in the meeting showed once and for all that he could not be trusted, no matter how gifted he was, and that his continued presence on the project would jeopardize its integrity. Eduardo was furious, but not really surprised. His past two jobs has also ended badly. As he was packing up his private belongings back in the lab, he made a point of sarcastically congratulating his co-

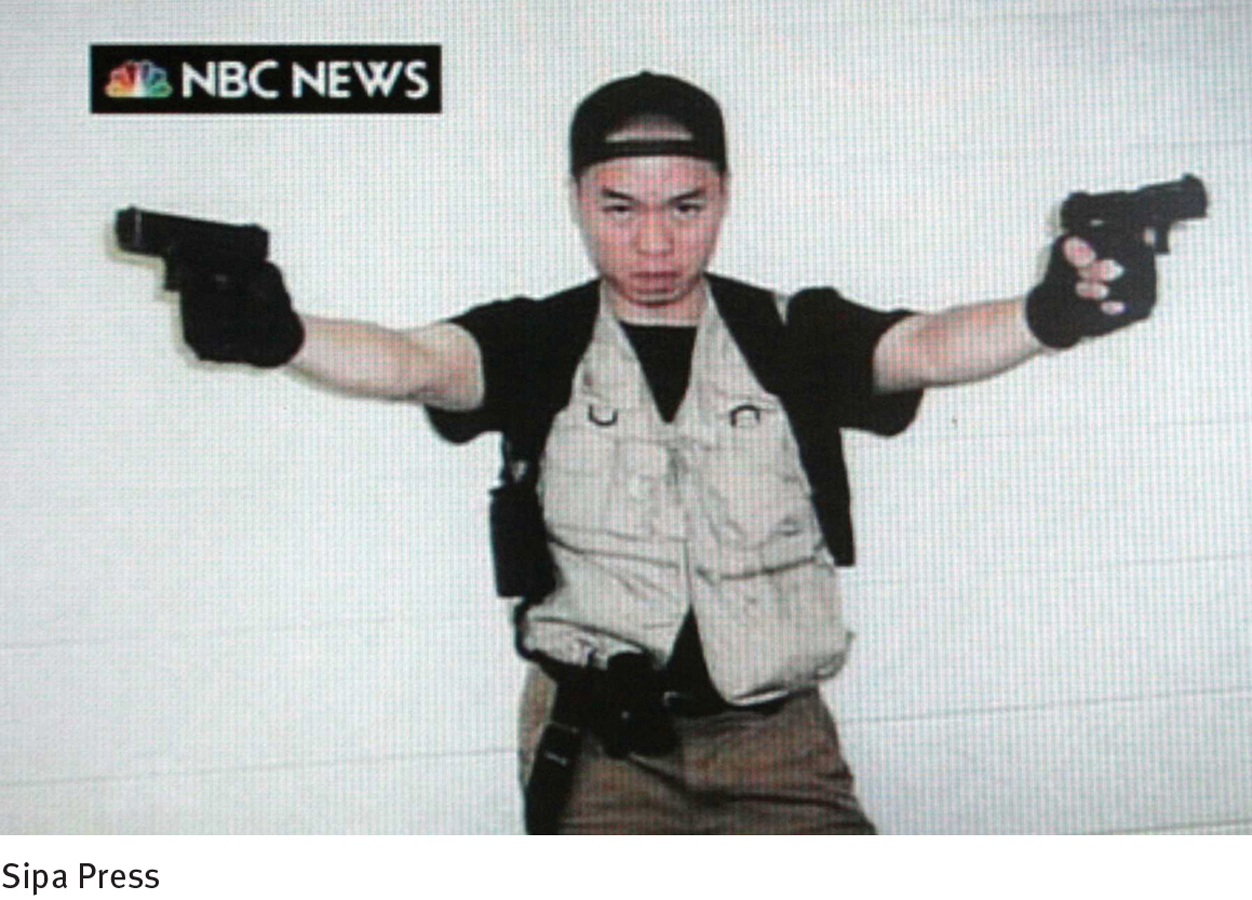

Ever on guard and cautious and seeing threats everywhere, people like Eduardo continually expect to be the targets of some trickery (see Figure 16-2). They find “hidden” meanings, which are usually belittling or threatening, in everything. In a study that required people to role-

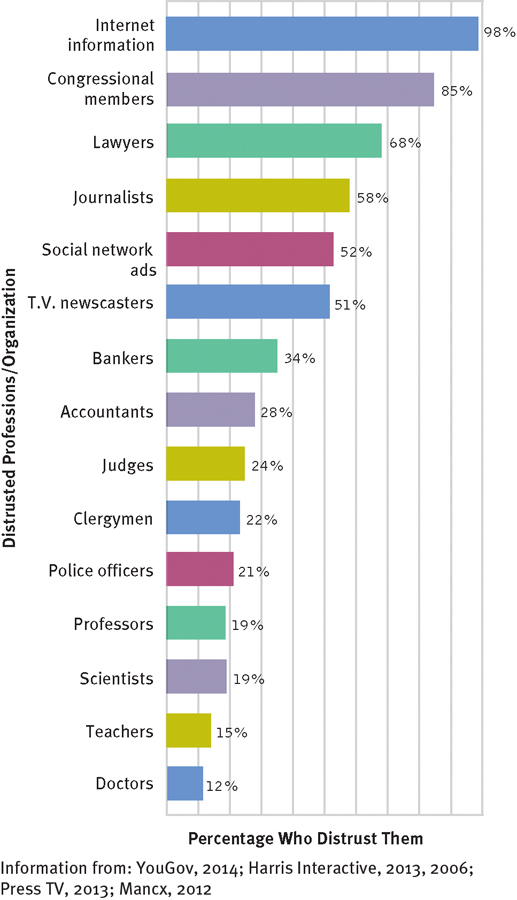

Whom do you distrust?

Although distrust and suspiciousness are the hallmarks of paranoid personality disorder, even people without this disorder are surprisingly untrusting. In various surveys, the majority of respondents said they distrust Internet information, members of Congress, lawyers, journalists, social network ads, and television newscasters. (Information from: YouGov, 2014; Harris Interactive, 2013, 2006; Press TV, 2013; Mancx, 2012).

Quick to challenge the loyalty or trustworthiness of acquaintances, people with paranoid personality disorder remain cold and distant. A woman might avoid confiding in anyone, for example, for fear of being hurt; or a husband might, without any justification, persist in questioning his wife’s faithfulness. Although inaccurate and inappropriate, their suspicions are not usually delusional; the ideas are not so bizarre or so firmly held as to clearly remove the individuals from reality (Millon, 2011).

People with this disorder are critical of weakness and fault in others, particularly at work (McGurk et al., 2013). They are unable to recognize their own mistakes, though, and are extremely sensitive to criticism. They often blame others for the things that go wrong in their lives, and they repeatedly bear grudges (Rotter, 2011). As many as 4.4 percent of adults in the United States experience this disorder, which is apparently more common in men than in women (APA, 2013; Sansone & Sansone, 2011).

How Do Theorists Explain Paranoid Personality Disorder?The theories that have been proposed to explain paranoid personality disorder, like those about most other personality disorders, have received little systematic research (Triebwasser et al., 2013). Psychodynamic theories, the oldest of these explanations, trace the pattern to early interactions with demanding parents, particularly distant, rigid fathers and overcontrolling, rejecting mothers (Caligor & Clarkin, 2010; Williams, 2010). (You will see that psychodynamic explanations for almost all the personality disorders begin the same way—

Biological theorists propose that paranoid personality disorder has genetic causes (APA, 2013; Bernstein & Useda, 2007). An early study that looked at self-

Treatments for Paranoid Personality DisorderPeople with paranoid personality disorder do not typically see themselves as needing help, and few come to treatment willingly (Millon, 2011). Furthermore, many who are in treatment view the role of patient as inferior and distrust and rebel against their therapists (Kellett & Hardy, 2013; Bender, 2005). Thus it is not surprising that therapy for this disorder, as for most other personality disorders, has limited effect and moves very slowly (Piper & Joyce, 2001).

Object relations therapists—

Schizoid Personality Disorder

People with schizoid personality disorder persistently avoid and are removed from social relationships and demonstrate little in the way of emotion (APA, 2013). Like people with paranoid personality disorder, they do not have close ties with other people. The reason they avoid social contact, however, has nothing to do with paranoid feelings of distrust or suspicion; it is because they genuinely prefer to be alone. Take Eli:

schizoid personality disorder A personality disorder characterized by persistent avoidance of social relationships and little expression of emotion.

schizoid personality disorder A personality disorder characterized by persistent avoidance of social relationships and little expression of emotion.

Eli, a student at the local technical institute, had been engaged in several different Internet certificate programs over the past few years, and was about to engage in yet another, when his mother, confused as to why he would not apply for a traditional degree at a “real” college, insisted he seek therapy. A loner by nature, Eli preferred not to socialize in any traditional sense, having little to no desire to get to know much about the people in his immediate social context. The way Eli saw it, … “at least at my school you just go to class and go home.”

Routinely, he slept through much of his day and then spent his evenings, nights, and weekends at the school’s computer lab, “chatting” with others over the Internet while not in class. Notably, people that he chatted with often sought to meet Eli, but he always declined these invitations, stating that he didn’t really have any desire to learn more about them than what they shared over the computer in the chat rooms. He described a family life that was similar to that of his social surroundings; he was mostly oblivious of his younger brother and sister, two outgoing teens, despite the fact that they seemed to hold him in the highest regard, and he had recently alienated himself entirely from his father, who had left the family several years earlier….

A marked deficit in social interest was notable in Eli, as were frequent behavioral eccentricities…. At best, he had acquired a peripheral … role in social and family relationships…. Rather than venturing outward, he had increasingly removed himself from others and from sources of potential growth and gratification. Life was uneventful, with extended periods of solitude interspersed.

(Millon, 2011)

People like Eli, often described as “loners,” make no effort to start or keep friendships, take little interest in having sexual relationships, and even seem indifferent to their families. They seek out jobs that require little or no contact with others. When necessary, they can form work relations to a degree, but they prefer to keep to themselves. Many live by themselves as well. Not surprisingly, their social skills tend to be weak. If they marry, their lack of interest in intimacy may create marital or family problems.

People with schizoid personality disorder focus mainly on themselves and are generally unaffected by praise or criticism. They rarely show any feelings, expressing neither joy nor anger. They seem to have no need for attention or acceptance; are typically viewed as cold, humorless, or dull; and generally succeed in being ignored. This disorder is present in 3.1 percent of the adult population (APA, 2013; Sansone & Sansone, 2011). Men are slightly more likely to experience it than are women, and men may also be more impaired by it.

How Do Theorists Explain Schizoid Personality Disorder?Many psychodynamic theorists, particularly object relations theorists, propose that schizoid personality disorder has its roots in an unsatisfied need for human contact (Caligor & Clarkin, 2010; Kernberg & Caligor, 2005). The parents of people with this disorder, like those of people with paranoid personality disorder, are believed to have been unaccepting or even abusive of their children. Whereas people with paranoid symptoms react to such parenting chiefly with distrust, those with schizoid personality disorder are left unable to give or receive love. They cope by avoiding all relationships.

Cognitive theorists propose, not surprisingly, that people with schizoid personality disorder suffer from deficiencies in their thinking. Their thoughts tend to be vague, empty, and without much meaning, and they have trouble scanning the environment to arrive at accurate perceptions (Kramer & Meystre, 2010). Unable to pick up emotional cues from others, they simply cannot respond to emotions. As this theory might predict, children with schizoid personality disorder develop language and motor skills very slowly, whatever their level of intelligence (APA, 2013; Wolff, 2000, 1991).

Treatments for Schizoid Personality DisorderTheir social withdrawal prevents most people with schizoid personality disorder from entering therapy unless some other disorder, such as alcoholism, makes treatment necessary (Mittal et al., 2007). These clients are likely to remain emotionally distant from the therapist, seem not to care about their treatment, and make limited progress at best (Colli et al., 2014; Millon, 2011).

Cognitive-

Schizotypal Personality Disorder

People with schizotypal personality disorder display a range of interpersonal problems marked by extreme discomfort in close relationships, very odd patterns of thinking and perceiving, and behavioral eccentricities (APA, 2013). Anxious around others, they seek isolation and have few close friends. Some feel intensely lonely. The disorder is more severe than the paranoid and schizoid personality disorders, as we see in the case of 41-

schizotypal personality disorder A personality disorder characterized by extreme discomfort in close relationships, very odd patterns of thinking and perceiving, and behavioral eccentricities.

schizotypal personality disorder A personality disorder characterized by extreme discomfort in close relationships, very odd patterns of thinking and perceiving, and behavioral eccentricities.

Kevin was a night security guard at a warehouse, where he had worked since his high school graduation more than 20 years ago. His parents, both successful professionals, had been worried for many years, as Kevin seemed entirely disconnected from himself and his surroundings and had never taken initiative to make any changes, even toward a shift supervisory position. They therefore made the referral for therapy, and Kevin simply acquiesced. He explained that he liked his work, as it was a place where he could be by himself in a quiet atmosphere, away from anyone else. He described where he worked as “an empty warehouse; they don’t use it no more but they don’t want no one in there. It’s nice; ‘homey.’”

Throughout the … interview, Kevin remained aloof, never once looking at the counselor, usually answering questions with either one-

Kevin … often seemed to experience a separation between his mind and his physical body. There was a strange sense of nonbeing or nonexistence, as if his floating conscious awareness carried with it a depersonalized or identityless human form. Behaviorally, his tendency was to be drab, sluggish, and inexpressive. He … appeared bland, indifferent, unmotivated, and insensitive to the external world…. Most people considered him to be [a] strange person … who faded into the background, self-

(Millon, 2011)

BETWEEN THE LINES

A Common Belief

People who think that they have extrasensory abilities are not necessarily suffering from schizotypal personality disorder. In fact, 73 percent of Americans believe in some form of the paranormal or occult—

(Gallup Poll, 2005).

As with Kevin, the thoughts and behaviors of people with schizotypal personality disorder can be noticeably disturbed. These symptoms may include ideas of reference—beliefs that unrelated events pertain to them in some important way—

People with schizotypal personality disorder often have great difficulty keeping their attention focused. Correspondingly, their conversation is typically digressive and vague, even sprinkled with loose associations (Millon, 2011). Like Kevin, they tend to drift aimlessly and lead an idle, unproductive life (Hengartner et al., 2014). They are likely to choose undemanding jobs in which they can work below their capacity and are not required to interact with other people. Surveys suggest that 3.9 percent of adults—

How Do Theorists Explain Schizotypal Personality Disorder?Because the symptoms of schizotypal personality disorder so often resemble those of schizophrenia, researchers have hypothesized that similar factors may be at work in both disorders. A wide range of studies have supported such expectations (Hazlett et al., 2014; Rosell et al., 2014; Thompson et al., 2014). Investigators have found that schizotypal symptoms, like schizophrenic patterns, are often linked to family conflicts and to psychological disorders in parents. They have also learned that defects in attention and short-

Although these findings do suggest a close relationship between schizotypal personality disorder and schizophrenia, the personality disorder also has been linked to disorders of mood (Lentz, Robinson, & Bolton, 2010). More than half of people with schizotypal personality disorder also suffer from major depressive disorder at some point in their lives (APA, 2013). Moreover, relatives of people with depression have a higher than usual rate of schizotypal personality disorder, and vice versa. Thus, at the very least, this personality disorder is not tied exclusively to schizophrenia.

Treatments for Schizotypal Personality DisorderTherapy is as difficult in cases of schizotypal personality disorder as it is in cases of paranoid and schizoid personality disorders. Most therapists agree on the need to help these clients “reconnect” with the world and recognize the limits of their thinking and their powers. The therapists may thus try to set clear limits—

Cognitive-

Antipsychotic drugs have been given to people with schizotypal personality disorder, again because of the disorder’s similarity to schizophrenia. In low doses the drugs appear to have helped some people, usually by reducing certain of their thought problems (Rosenbluth & Sinyor, 2012; Silk & Jibson, 2010).