2.5 Alternative Experimental Designs

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“When my information changes, I alter my conclusions.”

John Maynard Keynes, economist

It is not easy to devise an experiment that is both well controlled and enlightening. Control of every possible confound is rarely achievable. Moreover, because psychological experiments typically use living beings, ethical and practical considerations limit the kinds of manipulations one can do (Manton et al., 2014). Thus clinical researchers must often settle for experimental designs that are less than ideal. The most common such variations are the quasi-

InfoCentral

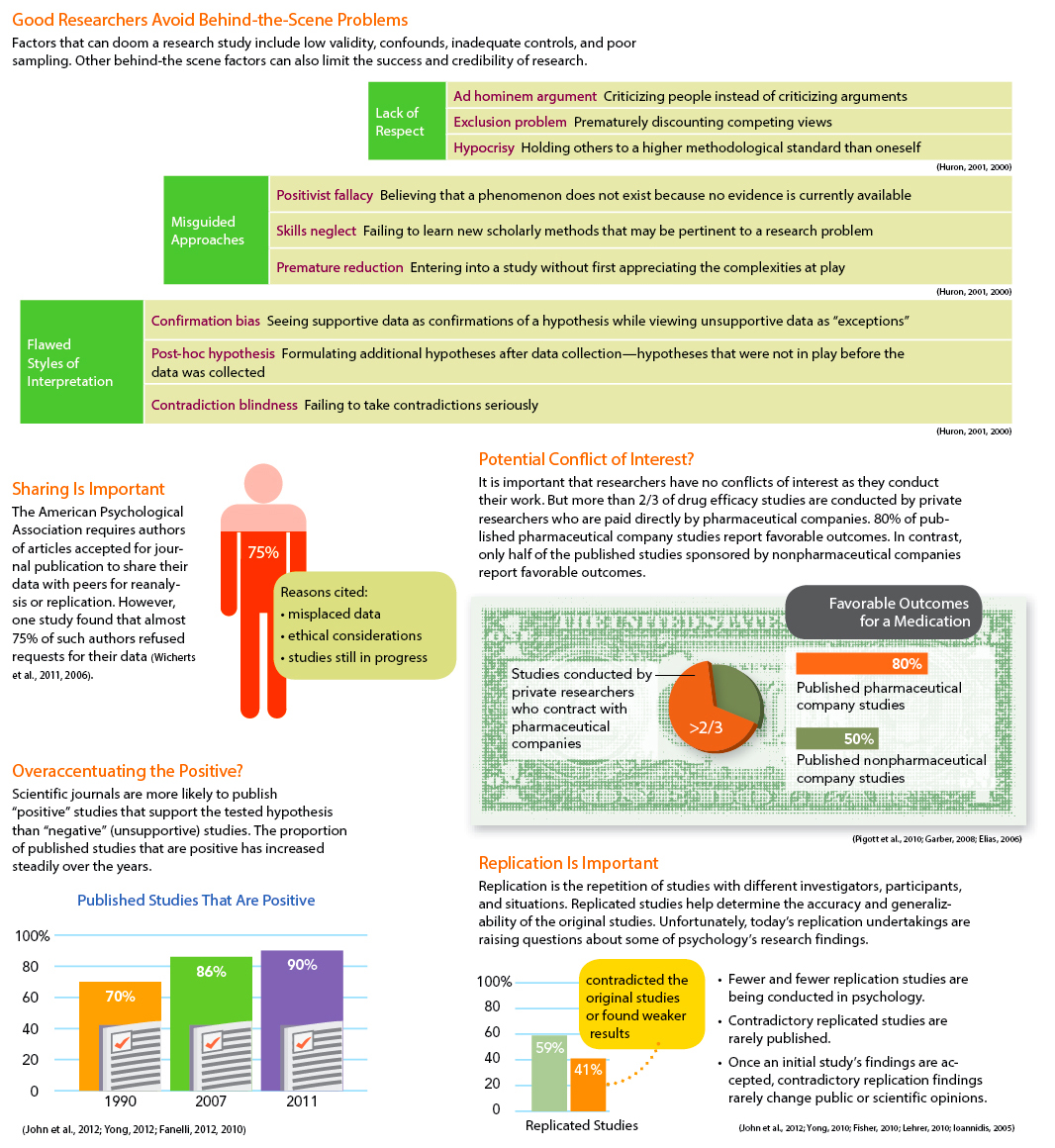

RESEARCH PITFALLS

Good research helps answer important questions and advance knowledge in a field. It is objective, carefully planned, clearly described, and aware of its own limitations. A good study features well-

Quasi-Experimental Design

In quasi-experiments, or mixed designs, investigators do not randomly assign participants to control and experimental groups but instead make use of groups that already exist in the world at large (Girden & Kabacoff, 2011; Remler & Van Ryzin, 2011). Consider, for example, research into the effects of child abuse. Because it would be unethical for investigators of this issue to actually abuse a randomly chosen group of children, they must instead compare children who already have a history of abuse with children who do not. Such a humane strategy is, of course, preferable, but at the same time, it violates the rule of random assignment and so introduces possible confounds into the study. Children who receive excessive physical punishment, for example, usually come from poorer and larger families than children who are punished verbally. Any differences found later in the moods or self-

quasi-experiment An experiment in which investigators make use of control and experimental groups that already exist in the world at large. Also called a mixed design.

quasi-experiment An experiment in which investigators make use of control and experimental groups that already exist in the world at large. Also called a mixed design.

Child-

Natural Experiments

In natural experiments, nature itself manipulates the independent variable, and the experimenter observes the effects. Natural experiments must be used for studying the psychological effects of unusual and unpredictable events, such as floods, earthquakes, plane crashes, and fires. Because the participants in these studies are selected by an accident of fate rather than by the investigators’ design, natural experiments are actually a kind of quasi-

natural experiment An experiment in which nature, rather than an experimenter, manipulates an independent variable.

natural experiment An experiment in which nature, rather than an experimenter, manipulates an independent variable.

On December 26, 2004, an earthquake occurred beneath the Indian Ocean off the coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. The earthquake triggered a series of massive tsunamis that flooded the ocean’s coastal communities, killed more than 225,000 people, and injured and left millions of survivors homeless, particularly in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, and Thailand. It was one of the deadliest natural disasters in history. Within months of this disaster, researchers conducted natural experiments in which they collected data from hundreds of survivors and from control groups of people who lived in areas not directly affected by the tsunamis. The disaster survivors scored significantly higher on anxiety and depression measures (dependent variables) than the controls did. The survivors also experienced more sleep problems, feelings of detachment, arousal, difficulties concentrating, startle responses, and guilt feelings than the controls did (Musa et al., 2014; Heir et al., 2010; Tang, 2007, 2006). Over the past several years, other natural experiments have focused on survivors of the 2010 Haitian earthquake, the massive earthquake and tsunami in Japan in 2011, the Northeast’s Superstorm Sandy in 2012, and the unprecedented Oklahoma tornados in 2013. These studies have also revealed lingering psychological symptoms among survivors of those disasters (Iwadare et al., 2013; Carey, 2011).

Because natural experiments rely on unexpected occurrences in nature, they cannot be repeated at will. Also, because each natural event is unique in certain ways, broad generalizations drawn from a single study could be incorrect. Nevertheless, catastrophes have provided opportunities for hundreds of natural experiments over the years, and certain findings have been obtained repeatedly. As a result, clinical scientists have identified patterns of reactions that people often have in such situations. You will read about these patterns—

Analogue Experiments

There is one way in which investigators can manipulate independent variables relatively freely while avoiding many of the ethical and practical limitations of clinical research. They can induce laboratory participants to behave in ways that seem to resemble real-

analogue experiment A research method in which the experimenter produces abnormal-

analogue experiment A research method in which the experimenter produces abnormal-

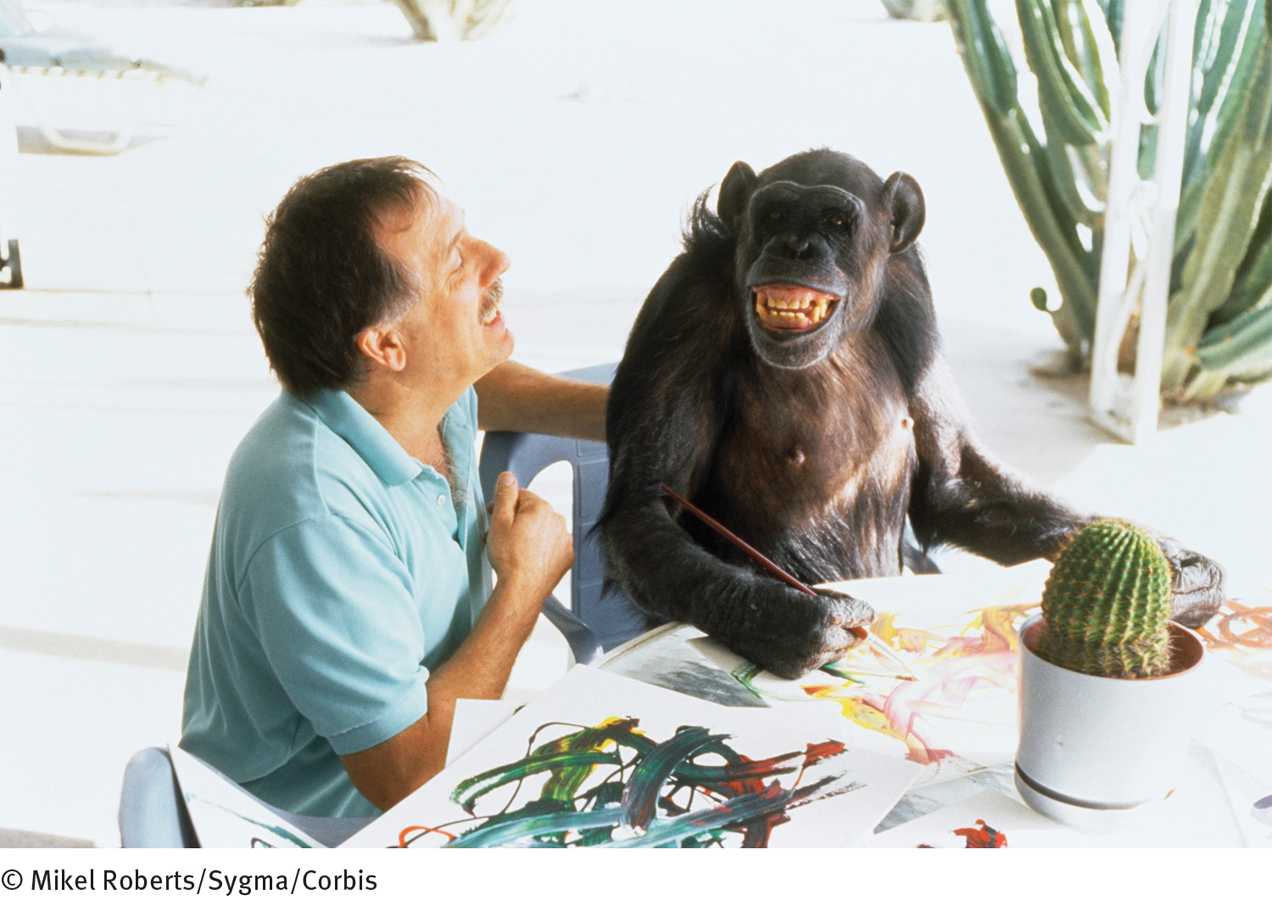

Do outside restrictions on research—

Analogue studies often use animals as participants. Animals are easier to gather and manipulate than humans, and their use poses fewer ethical problems. While the needs and rights of animal subjects must be considered, most experimenters are willing to subject animals to more discomfort than they would humans. They believe that the insights gained from such experimentation outweigh the discomfort of the animals, as long as their distress is not excessive (Bara & Jaffe, 2014; Barnard, 2007). In addition, experimenters can, and often do, use human participants in analogue experiments.

As you’ll see in Chapter 7, investigator Martin Seligman, in a classic body of work, has used analogue studies with great success to investigate the causes of human depression. Seligman has theorized that depression results when people believe they no longer have any control over the good and bad things that happen in their lives. To test this theory, he has produced depression-

It is important to remember that the laboratory-

Single-Subject Experiments

Sometimes scientists do not have the luxury of experimenting on many participants. They may, for example, be investigating a disorder so rare that few participants are available. Experimentation is still possible, however, with a single-subject experimental design. Here a single participant is observed both before and after the manipulation of an independent variable (Richards, Taylor, & Ramasamy, 2014). Single-

single-subject experimental design A research method in which a single participant is observed and measured both before and after the manipulation of an independent variable.

single-subject experimental design A research method in which a single participant is observed and measured both before and after the manipulation of an independent variable.

In one kind of single-

One researcher used an ABAB design to determine whether the systematic use of rewards was helping to reduce a teenage boy’s habit of disrupting his special education class with loud talk (Deitz, 1977). He rewarded the boy, who suffered from intellectual disability (previously called mental retardation), with extra teacher time whenever he went 55 minutes without interrupting the class more than three times. In condition A (baseline period), the student was observed to disrupt the class frequently with loud talk. In condition B, the boy was given a series of teacher reward sessions (introduction of the independent variable); as expected, his loud talk decreased dramatically. Then the rewards from the teacher were stopped (condition A again), and the student’s loud talk increased once again. Apparently the independent variable had indeed been the cause of the improvement. To be still more confident about this conclusion, the researcher had the teacher apply reward sessions yet again (condition B again). Once again the student’s behavior improved.

Obviously, single-