Chapter Introduction

| CHAPTER |

| 6 |

Disorders of Trauma and Stress

TOPIC OVERVIEW

What Triggers Acute and Posttraumatic Stress Disorders?

Why Do People Develop Acute and Posttraumatic Stress Disorders?

How Do Clinicians Treat Acute and Posttraumatic Stress Disorders?

Dissociative Amnesia

Dissociative Identity Disorder

How Do Theorists Explain Dissociative Amnesia and Dissociative Identity Disorder?

How Are Dissociative Amnesia and Dissociative Identity Disorder Treated?

Depersonalization-

Specialist Latrell Robinson, a 25-

On a routine convoy mission [in 2003], serving as driver for the lead HUMVEE, his vehicle was struck by an Improvised Explosive Device showering him with shrapnel in his neck, arm, and leg. Another member of his vehicle was even more seriously injured…. He was evacuated to the Combat Support Hospital (CSH) where he was treated and returned to duty … after several days despite requiring crutches and suffering chronic pain from retained shrapnel in his neck. He began to become angry at his command and doctors for keeping him in [Iraq] while he was unable to perform his duties effectively. He began to develop insomnia, hypervigilance, and a startle response. His initial dreams of the event became more intense and frequent and he suffered intrusive thoughts and flashbacks of the attack. He began to withdraw from his friends and suffered anhedonia, feeling detached from others, and he feared his future would be cut short. He was referred to a psychiatrist at the CSH….

After two months of unsuccessful rehabilitation for his battle injuries and worsening depressive and anxiety symptoms, he was evacuated to a … military medical center [in the United States]…. He was screened for psychiatric symptoms and was referred for outpatient evaluation and management. He met … criteria for acute PTSD and was offered medication management, supportive therapy, and group therapy…. He was ambivalent about taking passes or convalescent leave to his home because of fears of being “different, irritated, or aggressive” around his family or girlfriend. After three months at the military service center, he was [deactivated from service and] referred to his local VA Hospital to receive follow-

(National Center for PTSD, 2008)

During the horror of combat, soldiers often become highly anxious and depressed, confused and disoriented, even physically ill. Moreover, for many, like Latrell, these and related reactions to extraordinary stress or trauma continue well beyond the combat experience itself.

Of course, it is not just combat soldiers who are affected by stress. Nor does stress have to rise to the level of combat trauma to have a profound effect on psychological and physical functioning. Stress comes in all sizes and shapes, and we are all greatly affected by it.

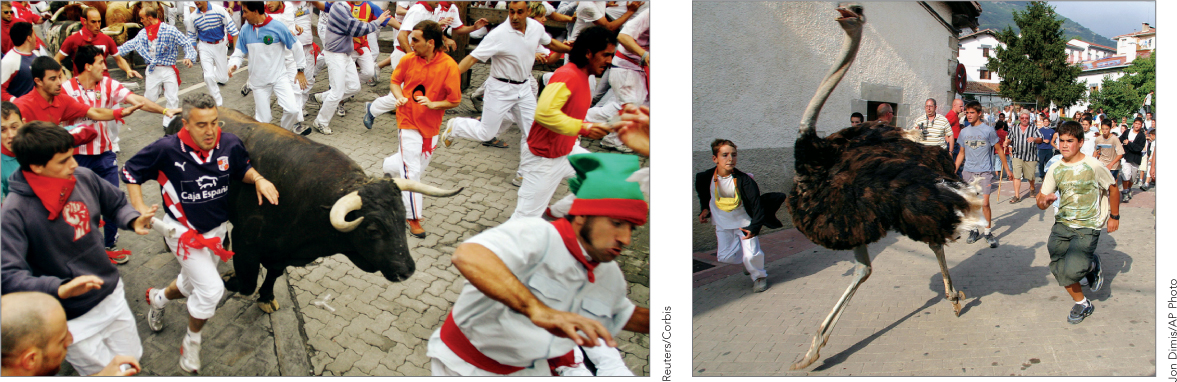

We feel some degree of stress whenever we are faced with demands or opportunities that require us to change in some manner. The state of stress has two components: a stressor, the event that creates the demands, and a stress response, the person’s reactions to the demands. The stressors of life may include annoying everyday hassles, such as rush-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Top Stressors in the U.S.

1. Job pressure

2. Money

3. Health

4. Relationships

5. Poor nutrition

6. Media overload

7. Sleep deprivation

(APA,2013)

When we view a stressor as threatening, a natural reaction is arousal and a sense of fear—

Stress reactions, and the sense of fear they produce, are often at play in psychological disorders. People who experience a large number of stressful events are particularly vulnerable to the onset of the anxiety disorders that you read about in Chapter 5. Similarly, increases in stress have been linked to the onset of depression, schizophrenia, sexual dysfunctioning, and other psychological problems.

Extraordinary stress and trauma play an even more central role in certain psychological disorders. In these disorders, the reactions to stress become severe and debilitating, linger for a long period of time, and may make it impossible for the individual to live a normal life. Under the heading “Trauma-

To fully understand these various stress-