6.2 Acute and Posttraumatic Stress Disorders

Of course when we actually confront stressful situations, we do not think to ourselves, “Oh, there goes my autonomic nervous system,” or “My fight-

For most people, such reactions subside soon after the danger passes. For others, however, the symptoms of anxiety and depression, as well as other kinds of symptoms, persist well after the upsetting situation is over. These people may be suffering from acute stress disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder, patterns that arise in reaction to a psychologically traumatic event. A traumatic event is one in which a person is exposed to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violation (APA, 2013). Unlike the anxiety disorders that you read about in Chapter 5, which typically are triggered by situations that most people would not find threatening, the situations that cause acute stress disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder—

If the symptoms begin within 4 weeks of the traumatic event and last for less than a month, DSM-

acute stress disorder A disorder in which a person experiences fear and related symptoms soon after a traumatic event but for less than a month.

acute stress disorder A disorder in which a person experiences fear and related symptoms soon after a traumatic event but for less than a month.

posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) A disorder in which a person continues to experience fear and related symptoms long after a traumatic event.

posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) A disorder in which a person continues to experience fear and related symptoms long after a traumatic event.

|

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder |

|

|---|---|

|

1. |

Person is exposed to a traumatic event— |

|

2. |

Person experiences at least one of the following intrusive symptoms: • Repeated, uncontrolled, and distressing memories • Repeated and upsetting trauma- |

|

3. |

Person continually avoids trauma- |

|

4. |

Person experiences negative changes in trauma- |

|

5. |

Person displays conspicuous changes in arousal and reactivity, such as excessive alertness, extreme startle responses, or sleep disturbances. |

|

6. |

Person experiences significant distress or impairment, with symptoms lasting more than a month. |

|

Information from: APA, 2013. |

|

Studies indicate that as many as 80 percent of all cases of acute stress disorder develop into posttraumatic stress disorder (Bryant et al., 2005). Think back to Latrell, the soldier in Iraq whose case opened this chapter. As you’ll recall, Latrell became overrun by anxiety, insomnia, worry, anger, depression, irritability, intrusive thoughts, flashback memories, and social detachment within days of the attack on his convoy mission—

REEXPERIENCING THE TRAUMATIC EVENTPeople may be battered by recurring thoughts, memories, dreams, or nightmares connected to the event (APA, 2013; Ruzek et al., 2011). A few relive the event so vividly in their minds (flashbacks) that they think it is actually happening again.

AVOIDANCEPeople usually avoid activities that remind them of the traumatic event and try to avoid related thoughts, feelings, or conversations (APA, 2013; Marx & Sloan, 2005).

REDUCED RESPONSIVENESSPeople feel detached from other people or lose interest in activities that once brought enjoyment. Some experience symptoms of dissociation, or psychological separation: they feel dazed, have trouble remembering things, or have a sense of derealization (feeling that the environment is unreal or strange) (APA, 2013; Ruzek et al., 2011).

INCREASED AROUSAL, NEGATIVE EMOTIONS, AND GUILTPeople with these disorders may feel overly alert (hyperalertness), be easily startled, have trouble concentrating, and develop sleep problems (APA, 2013). They may display anxiety, anger, or depression and feel extreme guilt because they survived the traumatic event while others did not (Worthen et al., 2014). Some also feel guilty about what they may have had to do to survive.

You can see these symptoms in the recollections of a Vietnam combat veteran years after he returned home:

I can’t get the memories out of my mind! The images come flooding back in vivid detail, triggered by the most inconsequential things, like a door slamming or the smell of stir-

(Davis, 1992)

What Triggers Acute and Posttraumatic Stress Disorders?

An acute or posttraumatic stress disorder can occur at any age, even in childhood, and can affect one’s personal, family, social, or occupational life (Alisic et al., 2014; Monson, Resick, & Rizvi, 2014). People with these stress disorders may also experience depression, another anxiety disorder, or substance abuse or become suicidal. Surveys indicate that at least 3.5 percent of people in the United States have one of the stress disorders in any given year; 7 to 9 percent suffer from one of them during their lifetimes (Kessler et al., 2012; Peterlin et al., 2011; Taylor, 2010). Around two-

What types of events in modern society might trigger acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder?

Women are at least twice as likely as men to develop stress disorders: around 20 percent of women who are exposed to a serious trauma may develop one, compared with 8 percent of men (Perrin et al., 2014; Koch & Haring, 2008; Russo & Tartaro, 2008). Moreover, people with low incomes are twice as likely as people with higher incomes to experience one of the stress disorders (Sareen et al., 2011).

Any traumatic event can trigger a stress disorder; however, some are particularly likely to do so. Among the most common are combat, disasters, and abuse and victimization.

CombatFor years clinicians have recognized that many soldiers develop symptoms of severe anxiety and depression during combat. It was called “shell shock” during World War I and “combat fatigue” during World War II and the Korean War (Figley, 1978). Not until after the Vietnam War, however, did clinicians learn that a great many soldiers also experience serious psychological symptoms after combat (Ruzek et al., 2011) (see MediaSpeak below).

By the late 1970s, it became apparent that many Vietnam combat veterans were still experiencing war-

A similar pattern unfolded among the nearly 2 million veterans of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (Ruzek et al., 2011). For example, a few years ago, the RAND Corporation, a nonprofit research organization, conducted a large-

It is also worth noting that the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq involved repeated deployments of many of the combat veterans and that the soldiers who served such multiple deployments were 50 percent more likely than those with one tour of service to have experienced severe combat stress, significantly raising their risk of developing posttraumatic stress disorder (Tyson, 2006).

DisastersAcute and posttraumatic stress disorders may also follow natural and accidental disasters such as earthquakes, floods, tornadoes, fires, airplane crashes, and serious car accidents (see Table 6-2). Researchers have found, for example, unusually high rates of posttraumatic stress disorder among the survivors of 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, 2010’s BP Gulf Coast oil spill, and the devastating tornado that struck Moore, Oklahoma, in 2013 (Pearson, 2013; Voelker, 2010). In fact, because they occur more often, civilian traumas have been the trigger of stress disorders at least 10 times as often as combat traumas (Bremner, 2002). Studies have even found that between 15 and 40 percent of people involved in traffic accidents—

|

Disaster |

Year |

Location |

Number Killed |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Flood |

1931 |

Huang River, China |

3,700,000 |

|

Tsunami |

2004 |

South Asia |

280,000 |

|

Earthquake |

1976 |

Tangshan, China |

255,000 |

|

Heat wave |

2003 |

Europe |

35,000 |

|

Volcano |

1985 |

Nevado del Ruiz, Colombia |

23,000 |

|

Hurricane |

1998 |

(Mitch) Central America |

18,277 |

|

Landslide |

1970 |

Yungay, Peru |

17,500 |

|

Avalanche |

1916 |

Italian Alps |

10,000 |

|

Blizzard |

1972 |

Iran |

4,000 |

|

Tornado |

1989 |

Saturia, Bangladesh |

1,300 |

|

Information from: USGS, 2011; CBC, 2008; Ash, 2001. |

|||

MediaSpeak

Combat Trauma Takes the Stand

By Deborah Sontag and Lizette Alvarez, The New York Times

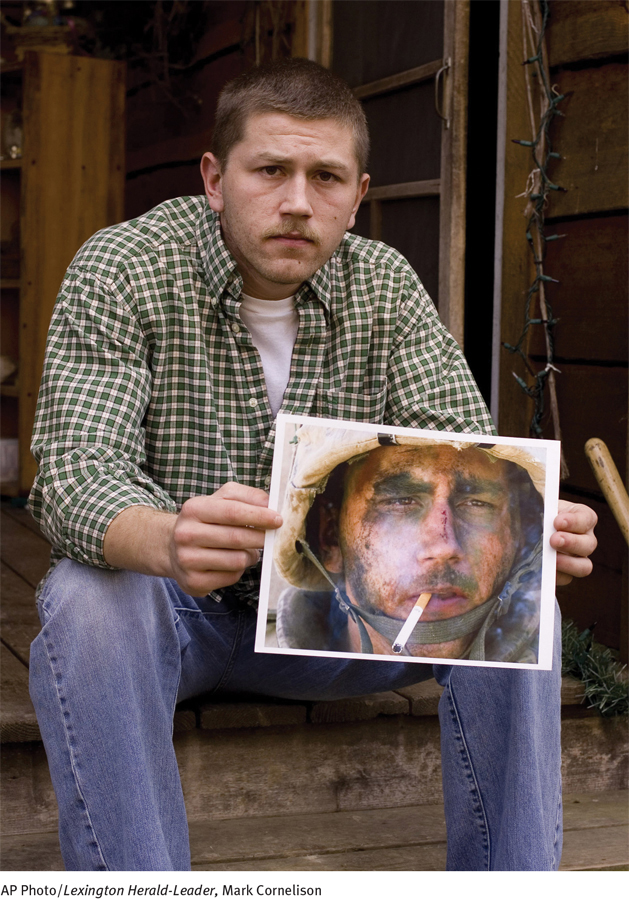

When it came time to sentence James Allen Gregg for his conviction on murder charges, the judge in South Dakota took a moment to reflect on the defendant as an Iraq combat veteran who suffered from severe posttraumatic stress disorder.

“This is a terrible case, as all here have observed,” said Judge Charles B. Kornmann of United States District Court. “Obviously not all the casualties coming home from Iraq or Afghanistan come home in body bags.” …

When combat veterans like Mr. Gregg stand accused of killings and other offenses on their return from Iraq and Afghanistan, prosecutors, judges and juries are increasingly prodded to assess the role of combat trauma in their crimes. … [M]ore and more, with the troops’ mental health a rising concern, these defendants … are arguing that war be seen as the backdrop for these crimes, most of which are committed by individuals without criminal records.

“I think they should always receive some kind of consideration for the fact that their mind has been broken by war,” said [a] Western regional defense counsel for the Marines. …

On the evening of July 3, 2004, Mr. Gregg, then 22, spent the night with friends in a roving pre-

According to the prosecutor, Mr. Gregg got upset because a young woman accompanying him gravitated to another man. This, the prosecutor said, led to Mr. Gregg spinning the wheels of his truck and spraying gravel on a car belonging to James Fallis, 26, a former high school football lineman. … Some time later, a confrontation ensued. Mr. Gregg was severely beaten by Mr. Fallis and, primarily, by another man, suffering facial fractures. Later that night, with one eye swollen shut and a fat lip, he drove to Mr. Fallis’s neighborhood.

Mr. Fallis emerged from a trailer, removed his jacket, asked Mr. Gregg if he had come back for more and opened the door to Mr. Gregg’s pickup truck. Mr. Gregg then reached for the pistol that he carried with him after his return from Iraq. He pointed it at Mr. Fallis and warned him to back away.

Mr. Fallis moved toward the trunk of his car, and Mr. Gregg testified that he believed Mr. Fallis was going to get a weapon. He started shooting to stop him, he said, and then Mr. Fallis veered toward his house. Mr. Gregg fired nine times, and struck [and killed] Mr. Fallis with five bullets.

Mr. Gregg drove quickly away, ending up in a pasture near his parents’ house. … According to Mr. Gregg’s testimony, he then put a magazine of more bullets in his gun, chambered a round and pointed it at his chest.

“Jim, why were you going to kill yourself?” his lawyer asked in court. … “Because it felt like Iraq had come back,” Mr. Gregg said. “I felt hopeless. … I never wanted to shoot him. Never wanted to hurt him. Never. Everything happened just so fast. I mean, it was almost instinct that I had to protect myself.” …

How much should juries and judges take a defendant’s PTSD into consideration when arriving at a verdict?

Mental health experts for the defense said, as one psychiatrist testified, that “PTSD was the driving force behind Mr. Gregg’s actions” when he shot his victim. Having suffered a severe beating, they said, he experienced an exaggerated “startle reaction”—a characteristic of PTSD—

The jury found Mr. Gregg guilty of second-

January 27, 2008 “WAR TORN; Combat Trauma Takes the Witness Stand” Sontag, Deborah and Alvarez, Lizette. From The New York Times, 1/27/2008 © 2008 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without express written permission is prohibited.

VictimizationPeople who have been abused or victimized often have stress symptoms that linger. Research suggests that more than one-

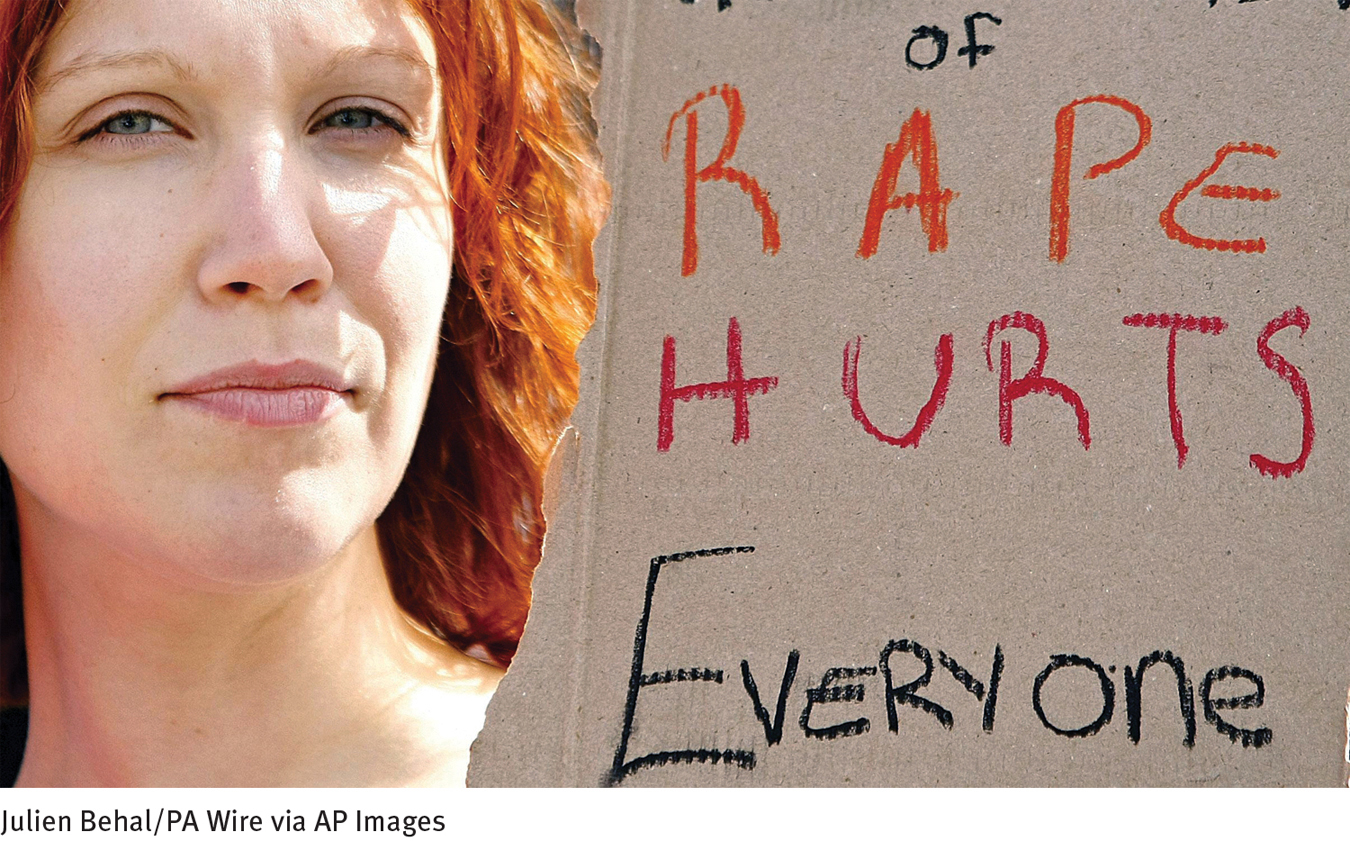

SEXUAL ASSAULTA common form of victimization in our society today is sexual assault (see InfoCentral below). Rape is forced sexual intercourse or another sexual act committed against a nonconsenting person or intercourse between an adult and an underage person. In the United States, approximately 100,000 cases of rape or attempted rape are reported to the police each year (Berzofsky et al., 2013; Koss, White, & Kazdin, 2011; Wolitzky-

rape Forced sexual intercourse or another sexual act committed against a nonconsenting person or intercourse between an adult and an underage person.

rape Forced sexual intercourse or another sexual act committed against a nonconsenting person or intercourse between an adult and an underage person.

The rates of rape differ from race to race. Around 27 percent of American Indian women and 22 percent of African American women have been raped at some point in their lives, compared with 19 percent of white American women, 15 percent of Hispanic American women, and 12 percent of Asian American women (Black et al., 2011).

The psychological impact of rape on a victim is immediate and may last a long time (Koss et al., 2011, 2008; Koss, 2005, 1993). Rape victims typically experience enormous distress during the week after the assault. Stress continues to rise for the next 3 weeks, maintains a peak level for another month or so, and then starts to improve. In one study, 94 percent of rape victims fully qualified for a clinical diagnosis of acute stress disorder when they were observed around 12 days after the assault (Rothbaum et al., 1992). Although some rape victims improve psychologically within three or four months, for many others, the profound effects of their assault persist for up to 18 months or longer. Victims typically continue to have higher-

How might physicians, police, the courts, and other agents better meet the psychological needs of rape victims?

Female victims of rape and other crimes also are much more likely than other women to suffer serious long-

Ongoing victimization and abuse in the family—

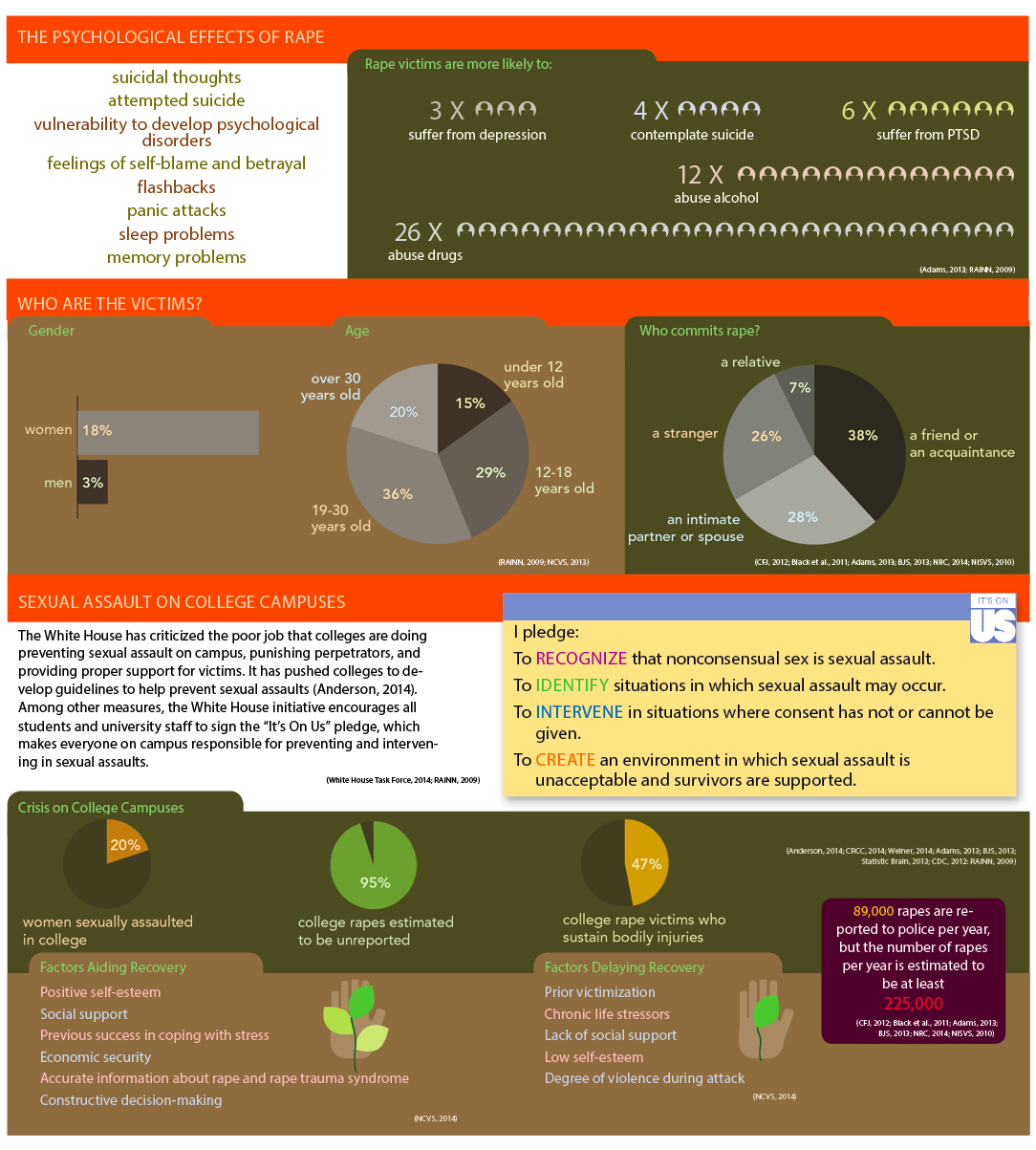

InfoCentral

SEXUAL ASSAULT

People who are sexually assaulted have been forced to engage in a sexual act against their will. According to most definitions, people who are raped have been forced into sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration. Rape victims often experience rape trauma syndrome (RTS), a pattern of problematic physical and psychological symptoms. RTS is actually a form of PTSD. Approximately one-

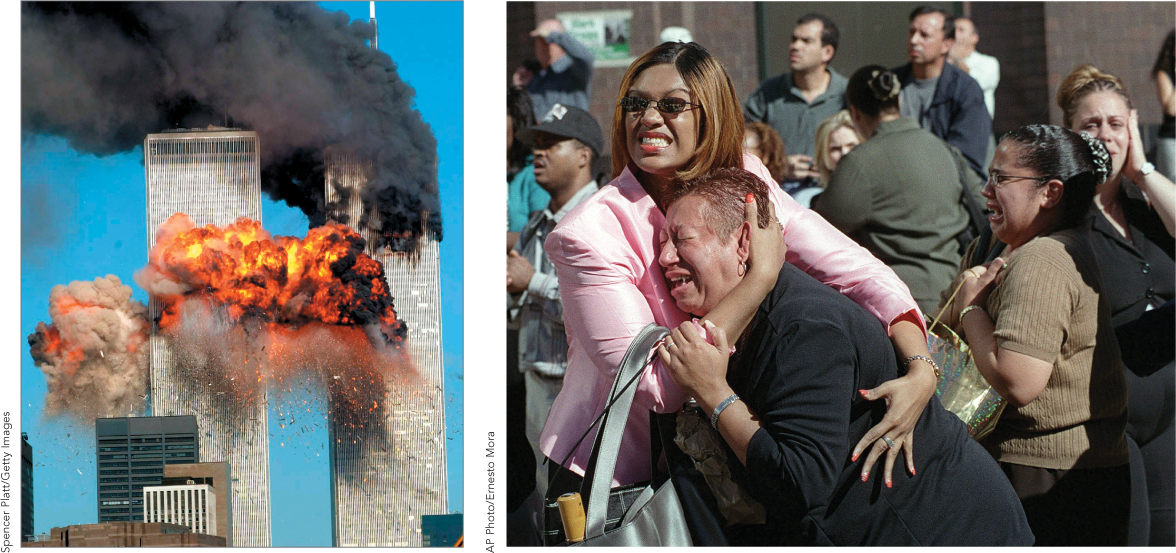

TERRORISMPeople who are victims of terrorism or who live under the threat of terrorism often experience posttraumatic stress symptoms (Ruggero et al., 2013; Mitka, 2011). Unfortunately, this source of traumatic stress is on the rise in our society. Few will ever forget the events of September 11, 2001, when hijacked airplanes crashed into and brought down the World Trade Center in New York City and partially destroyed the Pentagon in Washington, DC, killing thousands of victims and rescue workers and forcing thousands more to desperately run, crawl, and even dig their way to safety. A number of studies have indicated that in the aftermath of that fateful day, many individuals developed immediate and long-

In a survey conducted a week after the terrorist attacks, 560 randomly selected adults across the United States were interviewed. Forty-

Follow-

TORTURETorture refers to the use of “brutal, degrading, and disorienting strategies in order to reduce victims to a state of utter helplessness” (Okawa & Hauss, 2007). Often, it is done on the orders of a government or another authority to force persons to yield information or make a confession (Gerrity, Keane, & Tuma, 2001). The question of the morality of torturing prisoners who are considered suspects in the “war on terror” has been the subject of much discussion over the past several years.

torture The use of brutal, degrading, and disorienting strategies to reduce victims to a state of utter helplessness.

torture The use of brutal, degrading, and disorienting strategies to reduce victims to a state of utter helplessness.

It is hard to know how many people are in fact tortured around the world because such numbers are typically hidden by governments (Basoglu et al., 2001). It has been estimated, however, that between 5 and 35 percent of the world’s 15 million refugees have suffered at least one episode of torture and that more than 400,000 torture survivors from around the world now live in the United States (ORR, 2011, 2006; AI, 2000; Baker, 1992). Of course, these numbers do not take into account the many thousands of victims who have remained in their countries even after being tortured.

People from all walks of life are subjected to torture worldwide—

Torture victims often experience physical ailments as a result of their ordeal, from scarring and fractures to neurological problems and chronic pain. But many theorists believe that the lingering psychological effects of torture are even more problematic (Gjini et al., 2013; Punamäki et al., 2010). It appears that between 30 and 50 percent of torture victims develop posttraumatic stress disorder. Even for those who do not develop a full-

Why Do People Develop Acute and Posttraumatic Stress Disorders?

Clearly, extraordinary trauma can cause a stress disorder. The stressful event alone, however, may not be the entire explanation. Certainly, anyone who experiences an unusual trauma will be affected by it, but only some people develop a stress disorder (see PsychWatch below) (Elhai, Ford, & Naifeh, 2010). To understand the development of these disorders more fully, researchers have looked to the survivors’ biological processes, personalities, childhood experiences, social support systems, and cultural backgrounds and to the severity of the traumas.

Biological and Genetic FactorsInvestigators have learned that traumatic events trigger physical changes in the brain and body that may lead to severe stress reactions and, in some cases, to stress disorders (Pace & Heim, 2011; Walderhaug et al., 2011). They have, for example, found abnormal activity of the hormone cortisol and the neurotransmitter/hormone norepinephrine in the urine, blood, and saliva of combat soldiers, rape victims, concentration camp survivors, and survivors of other severe stresses (Gola et al., 2012; Gerardi et al., 2010).

Evidence from brain studies also shows that once a stress disorder sets in, it may lead to further biochemical arousal, and this continuing arousal may eventually damage key brain areas (Lee et al., 2014; Pace & Heim, 2011). As we have seen in earlier chapters, researchers have determined that emotional reactions of various kinds are tied to brain circuits—

PsychWatch

Adjustment Disorders: A Category of Compromise?

Some people react to a major stressor in their lives with extended and excessive feelings of anxiety, depressed mood, or antisocial behaviors. The symptoms do not quite add up to acute stress disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder, nor do they reflect an anxiety or mood disorder, but they do cause considerable distress or interfere with the person’s job, schoolwork, or social life. Should we consider such reactions normal? No, says DSM-

DSM-

Almost any kind of stressor may trigger an adjustment disorder. Common ones are the breakup of a relationship, marital problems, business difficulties, and living in a crime-

Up to 30 percent of all people in out-

Normally, the hippocampus plays a major role both in memory and in the regulation of the body’s stress hormones. Clearly, a dysfunctional hippocampus may help produce the intrusive memories and constant arousal found in posttraumatic stress disorder (Bremner et al., 2004). Similarly, as you read in Chapter 5, the amygdala helps control anxiety and many other emotional responses. It also works with the hippocampus to produce the emotional components of memory. Thus, a dysfunctional amygdala may help produce the repeated emotional symptoms and strong emotional memories common to people with posttraumatic stress disorder (Protopopescu et al., 2005). In short, the arousal produced by extraordinarily traumatic events may lead to stress disorders in some people, and the stress disorders may produce yet further brain abnormalities, locking in the disorders all the more firmly.

It may also be that posttraumatic stress disorder leads to the transmission of biochemical abnormalities to the children of people with the disorder. One team of researchers examined the cortisol levels of women who had been pregnant during the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and had developed PTSD (Yehuda & Bierer, 2007). Not only did these women have higher-

Many theorists believe that people whose biochemical reactions to stress are unusually strong are more likely than others to develop acute and posttraumatic stress disorders (Burijon, 2007). But why would certain people be prone to such strong biological reactions? One possibility is that the propensity is inherited (Clark et al., 2013). Clearly, this is suggested by the mother–

PersonalitySome studies suggest that people with certain personalities, attitudes, and coping styles are particularly likely to develop acute and posttraumatic stress disorders (DiGangi et al., 2013). In the aftermath of Hurricane Hugo in 1989, for example, children who had been highly anxious before the storm were more likely than other children to develop severe stress reactions (Hardin et al., 2002). Research has also found that people who generally view life’s negative events as beyond their control tend to develop more severe stress symptoms after sexual or other kinds of traumatic events than people who feel that they have more control over their lives (Catanesi et al., 2013; Bremner, 2002). Similarly, people who generally find it difficult to derive anything positive from unpleasant situations adjust more poorly after traumatic events than people who are generally resilient and who typically find value in negative events (Algoe & Fredrickson, 2011; Kunst, 2011).

Childhood ExperiencesResearchers have found that certain childhood experiences seem to leave some people at risk for later acute and posttraumatic stress disorders (Pervanidou & Chrousos, 2014). People whose childhoods have been marked by poverty appear more likely to develop these disorders in the face of later trauma. So do people who went through an assault, abuse, or a catastrophe at an early age; who were younger than 10 when their parents separated or divorced; or whose family members suffered from psychological disorders (Ogle et al., 2014; Yehuda et al., 2010; Koopman et al., 2004).

Do the vivid images seen daily on the Web, on TV, and in video games make people more vulnerable to developing psychological stress disorders or less vulnerable?

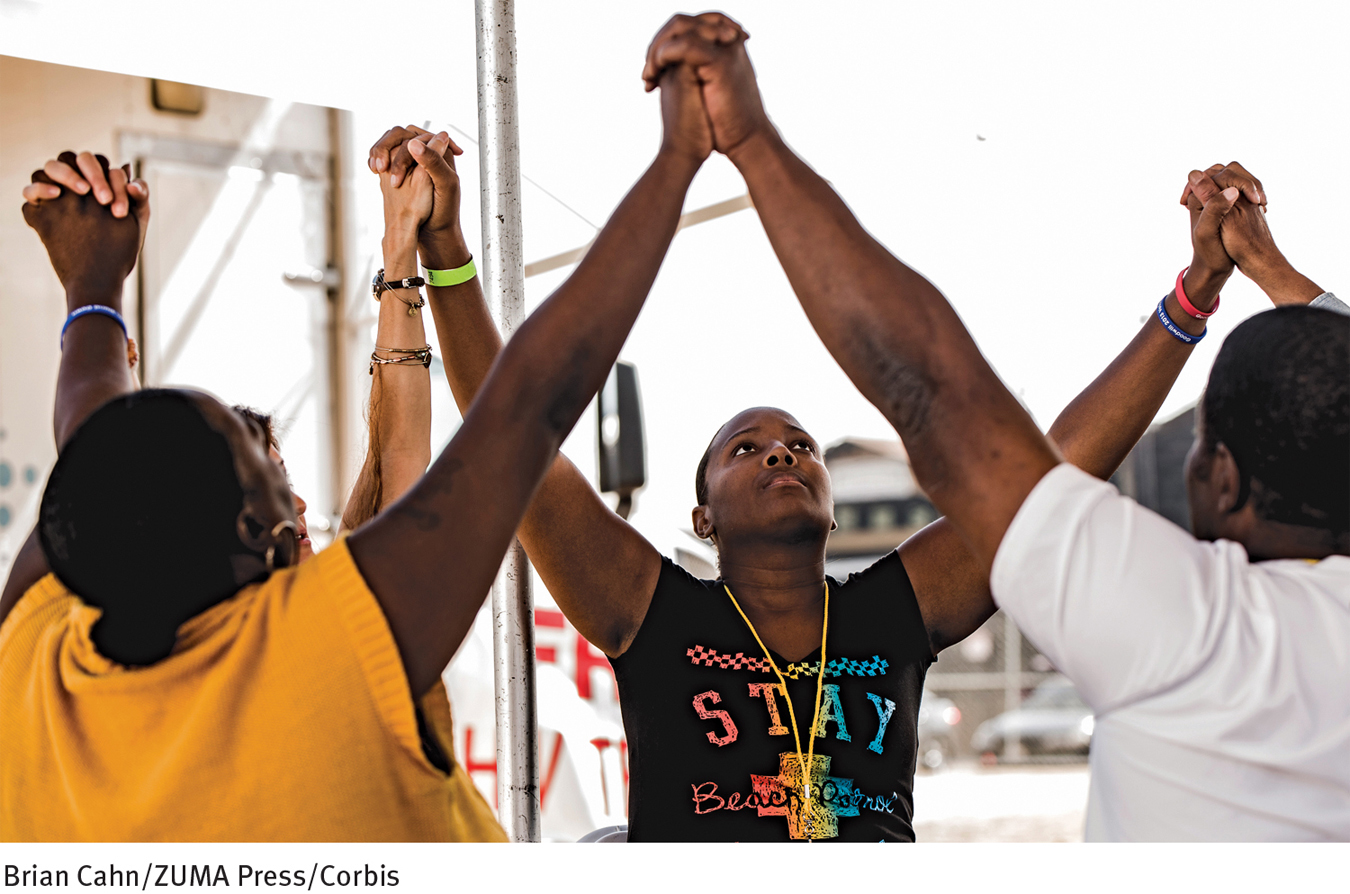

Social SupportPeople whose social and family support systems are weak are also more likely to develop acute or posttraumatic stress disorder after a traumatic event (DiGangi et al., 2013; Uchino & Birmingham, 2011). Rape victims who feel loved, cared for, valued, and accepted by their friends and relatives recover more successfully (Street et al., 2011). So do those treated with dignity and respect by the criminal justice system (Mouilso et al., 2011; Patterson, 2011). In contrast, clinical reports have suggested that poor social support contributes to the development of posttraumatic stress disorder in some combat veterans (Schumm et al., 2014; Charuvastra & Cloitre, 2008).

Multicultural FactorsThere is a growing suspicion among clinical researchers that the rates of posttraumatic stress disorder may differ among ethnic groups in the United States. In particular, Hispanic Americans may be more vulnerable to the disorder than other cultural groups (Koch & Haring, 2008; Galea et al., 2006). Some cases in point: (1) Studies of combat veterans from the wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Vietnam have found higher rates of posttraumatic stress disorder among Hispanic American veterans than among white American and African American veterans (RAND Corporation, 2010, 2008; Kulka et al., 1990). (2) In surveys of police officers, Hispanic American officers typically report more severe duty-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Stress and Coping: Eye on Culture

57 percent of American Indians and African Americans feel stressed by finances, compared with 47 percent of the entire American population.

41 percent of Hispanic Americans feel stressed by employment issues, compared with 32 percent of the entire American population.

(Information from: MHA, 2010, 2008)

Why might Hispanic Americans be more vulnerable to posttraumatic stress disorder than other racial or ethnic groups? Several explanations have been suggested. One holds that as part of their cultural belief system, many Hispanic Americans tend to view traumatic events as inevitable and unalterable, a coping response that may heighten their risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (Perilla et al., 2002). Another explanation suggests that their culture’s emphasis on social relationships and social support may place Hispanic American victims at special risk when traumatic events deprive them—

BETWEEN THE LINES

Personal Impact of Stress

|

33 |

Percentage of people who feel they are living with extreme stress |

|

35 |

Percentage of people who report feeling more stress this year than last year |

|

48 |

Percentage of people who lie awake at night due to stress |

|

48 |

Percentage of people who say stress negatively affects their personal and professional lives |

|

54 |

Percentage of people who say stress has caused them to fight with close friends or relatives |

(Information from: APA, 2013)

Severity of TraumaAs you might expect, the severity and nature of the traumatic event that a person goes through help determine whether the person will develop a stress disorder. Some events can override even a nurturing childhood, positive attitudes, and social support (Ogle, Rubin, & Siegler, 2014; Tramontin & Halpern, 2007). One study examined 253 Vietnam War prisoners five years after their release. Some 23 percent qualified for a clinical diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder, though all had been evaluated as well adjusted before their imprisonment (Ursano et al., 1981).

Generally, the more severe the trauma and the more direct one’s exposure to it, the higher the likelihood of developing a stress disorder (Ogle et al., 2014). Mutilation, severe physical injury, or sexual abuse in particular seem to increase the risk of stress reactions, as does witnessing the injury or death of other people (Perrin et al., 2014; Ursano et al., 2003).

How Do Clinicians Treat Acute and Posttraumatic Stress Disorders?

Treatment can be very important for people who have been overwhelmed by traumatic events (Church, 2014; Taylor, 2010). Overall, about half of all cases of posttraumatic stress disorder improve within six months (Asnis et al., 2004). The remainder of cases may persist for years, and, indeed, more than one-

Today’s treatment procedures for troubled survivors typically vary from trauma to trauma. Was it combat, an act of terrorism, sexual molestation, or a major accident? Yet all the programs share basic goals: they try to help survivors put an end to their stress reactions, gain perspective on their painful experiences, and return to constructive living (Taylor, 2010). Programs for combat veterans who suffer from PTSD illustrate how these issues may be addressed.

Treatment for Combat VeteransTherapists have used a variety of techniques to reduce veterans’ posttraumatic symptoms. Among the most common are drug therapy, behavioral exposure techniques, insight therapy, family therapy, and group therapy. Typically the approaches are combined, as no one of them successfully reduces all the symptoms (Mott et al., 2014; Rothbaum et al., 2014; Vogt et al., 2011).

Antianxiety drugs help control the tension that many veterans experience (Writer, Meyer, & Schillerstrom, 2014). In addition, antidepressant medications may reduce the occurrence of nightmares, panic attacks, flashbacks, and feelings of depression (Morgan et al., 2012; Koch & Haring, 2008).

MindTech

Virtual Reality Therapy: Better than the Real Thing?

As you have read, exposure-

All that changed a decade ago, when “virtual” exposure to combat conditions became available for veterans with PTSD. The Office of Naval Research funded the development of “Virtual Iraq,” a war simulation treatment game (McIlvaine, 2011). This game was able to produce sights and sounds that seemed every bit as real and produced as much—

In virtual reality therapy, PTSD clients use wraparound goggles and joysticks to navigate their way through a computer-

Can you design a virtual reality exposure treatment program for people with social anxiety disorder?

Study after study has suggested that virtual reality therapy is extremely helpful for combat veterans with PTSD, much more so than covert exposure therapy (Nauert, 2014; McLay, 2013; Rauch, Eftekhari, & Ruzek, 2012). In addition, the improvements produced by this intervention appear to last for extended periods, perhaps indefinitely. Small wonder that virtual reality therapy is now also becoming common in the treatment of other anxiety disorders and phobias, including social anxiety disorder and fears of heights, flying, and closed spaces (Anderson et al., 2013). ![]()

BETWEEN THE LINES

The Smell of Stress?

Stress is odorless. The bacteria that feed off of our sweat are what give our bodies odor during very stressful events.

Behavioral exposure techniques, too, have helped reduce specific symptoms, and they have often led to improvements in overall adjustment (Peterson, Foa, & Riggs, 2011). In fact, some studies indicate that exposure treatment is the single most helpful intervention for people with posttraumatic stress disorder (Powers et al., 2010; Williams, Cahill, & Foa, 2010). This finding suggests to many clinical theorists that exposure of one kind or another should always be part of the treatment picture (see MindTech above). In one case, the exposure technique of flooding, along with relaxation training, helped rid a 31-

A widely applied form of exposure therapy is eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), in which clients move their eyes in a rhythmic manner from side to side while flooding their minds with images of the objects and situations they ordinarily try to avoid. Case studies and controlled studies suggest that this treatment can often be helpful to people with posttraumatic stress disorder (Rothbaum et al., 2011; Russell et al., 2011). Many theorists argue that it is the exposure feature of EMDR, rather than the eye movement, that accounts for its success as a treatment for PTSD (Lamprecht et al., 2004).

eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) An exposure treatment in which clients move their eyes in a rhythmic manner from side to side while flooding their minds with images of objects and situations they ordinarily avoid.

eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) An exposure treatment in which clients move their eyes in a rhythmic manner from side to side while flooding their minds with images of objects and situations they ordinarily avoid.

Although drug therapy and exposure techniques bring some relief, most clinicians believe that veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder cannot fully recover with these approaches alone: they must also come to grips in some way with their combat experiences and the impact those experiences continue to have (Rothbaum et al., 2011; Burijon, 2007). Thus clinicians often try to help veterans bring out deep-

Veterans who have posttraumatic stress disorder may be further helped in a couple, family, or group therapy format (Shnaider et al., 2014; Vogt et al., 2011). The symptoms of PTSD are particularly apparent to family members, who may be directly affected by the client’s anxieties, depressed mood, or angry outbursts (Owens et al., 2014; Monson et al., 2011). With the help and support of their family members, they may come to examine their impact on others, learn to communicate better, and improve their problem-

In group therapy sessions, called rap groups when initiated during the 1980s, the veterans meet with others like themselves to share experiences and feelings (particularly guilt and rage), develop insights, and give mutual support (Ellis et al., 2014; Foy et al., 2011).

rap groups The initial term for group therapy sessions among veterans, in which members meet to talk about and explore problems in an atmosphere of mutual support.

rap groups The initial term for group therapy sessions among veterans, in which members meet to talk about and explore problems in an atmosphere of mutual support.

Today hundreds of small Veterans Outreach Centers across the country, as well as treatment programs in Veterans Administration hospitals and mental health clinics, provide group treatment (Ruzek & Batten, 2011). These agencies also offer individual therapy, counseling for spouses and children, family therapy, and aid in seeking jobs, education, and benefits (Mott et al., 2014). Clinical reports suggest that these programs offer a necessary, sometimes life-

Psychological DebriefingPeople who are traumatized by disasters, victimization, or accidents profit from many of the same treatments that are used to help survivors of combat (Monson et al., 2014). In addition, because their traumas occur in their own community, where mental health resources are close at hand, they may, according to many clinicians, further benefit from immediate community interventions.

One of the leading such approaches is called psychological debriefing, or critical incident stress debriefing, an intervention applied widely over the past 30 years. The use of this intervention has, however, come under careful scrutiny in recent years, reminding the clinical field of the ongoing need for systematic research into its assumptions and applications.

psychological debriefing A form of crisis intervention in which victims are helped to talk about their feelings and reactions to traumatic incidents. Also called critical incident stress debriefing.

psychological debriefing A form of crisis intervention in which victims are helped to talk about their feelings and reactions to traumatic incidents. Also called critical incident stress debriefing.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Gender and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Many researchers believe that women’s higher rates of posttraumatic stress disorder are tied to the types of violent traumas they experience—

Psychological debriefing is a form of crisis intervention that has victims of trauma talk extensively about their feelings and reactions within days of the critical incident (Tuckey & Scott, 2014; Gist & Devilly, 2010; Mitchell, 2003, 1983). Based on the assumption that such sessions prevent or reduce stress reactions, they are often provided to trauma victims who have not yet displayed any symptoms at all, as well as to those who have. During the sessions, often conducted in a group format, counselors guide the individuals to describe the details of the recent trauma, to vent and relive the emotions provoked at the time of the event, and to express their current feelings. The clinicians then clarify to the victims that their reactions are perfectly normal responses to a terrible event, offer stress management tips, and in some cases, refer the victims to professionals for long-

Many thousands of counselors, both professionals and nonprofessionals, have been trained in psychological debriefing since its inception in the early 1980s, and the intense approach has been applied in the aftermath of countless traumatic events (Pfefferbaum, Newman, & Nelson, 2014; Wei et al., 2010; McNally, 2004). Indeed, when a traumatic incident affects numerous individuals, debriefing-

In such community-

Does Psychological Debriefing Work?Over the years, personal testimonials for rapid mobilization programs have often been favorable (Watson & Shalev, 2005; Mitchell, 2003). However, as you read earlier, a growing number of studies conducted in the twenty-

Actually, an investigation conducted in the early 1990s was the first to raise concerns about disaster debriefing programs (Bisson & Deahl, 1994). Crisis counselors offered immediate debriefing sessions to 62 British soldiers whose job during the Gulf War was to handle and identify the bodies of people who had been killed. Despite such sessions, half of the soldiers displayed posttraumatic stress symptoms when interviewed nine months later.

In a properly controlled study conducted a few years later on hospitalized burn victims, researchers separated the victims into two groups (Bisson et al., 1997). One group received a single one-

More recent studies, focusing on yet other kinds of disasters, have yielded similar patterns of findings, raising important questions about the effectiveness of psychological debriefing (Tuckey & Scott, 2014; Szumilas et al., 2010). Some clinicians have come to believe that the early intervention programs may encourage victims to dwell too long on the traumatic events that they have experienced. And a number worry that early disaster counseling may unintentionally “suggest” problems to certain victims, thus helping to produce stress disorders (McNally, 2004; McClelland, 1998).

Many mental health professionals continue to believe in psychological debriefing programs. However, given the unsupportive and even contradictory research findings of recent years, the current clinical climate is moving away from outright acceptance. A number of clinical theorists now believe that certain high-