3.5 The Humanistic-Existential Model

Philip Berman is more than the sum of his psychological conflicts, learned behaviors, or cognitions. Being human, he also has the ability to pursue philosophical goals such as self-

Humanists, the more optimistic of the two groups, believe that human beings are born with a natural tendency to be friendly, cooperative, and constructive. People, these theorists propose, are driven to self-actualize—that is, to fulfill this potential for goodness and growth. They can do so, however, only if they honestly recognize and accept their weaknesses as well as their strengths and establish satisfying personal values to live by. Humanists further suggest that self-

self-actualization The humanistic process by which people fulfill their potential for goodness and growth.

self-actualization The humanistic process by which people fulfill their potential for goodness and growth.

Existentialists agree that human beings must have an accurate awareness of themselves and live meaningful—

The humanistic and existential views of abnormality both date back to the 1940s. At that time Carl Rogers (1902-

client-centered therapy The humanistic therapy developed by Carl Rogers in which clinicians try to help clients by conveying acceptance, accurate empathy, and genuineness.

client-centered therapy The humanistic therapy developed by Carl Rogers in which clinicians try to help clients by conveying acceptance, accurate empathy, and genuineness.

The existential view of personality and abnormality appeared during this same period. Many of its principles came from the ideas of nineteenth-

The humanistic and existential theories, and their uplifting implications, were extremely popular during the 1960s and 1970s, years of considerable soul-

Rogers’ Humanistic Theory and Therapy

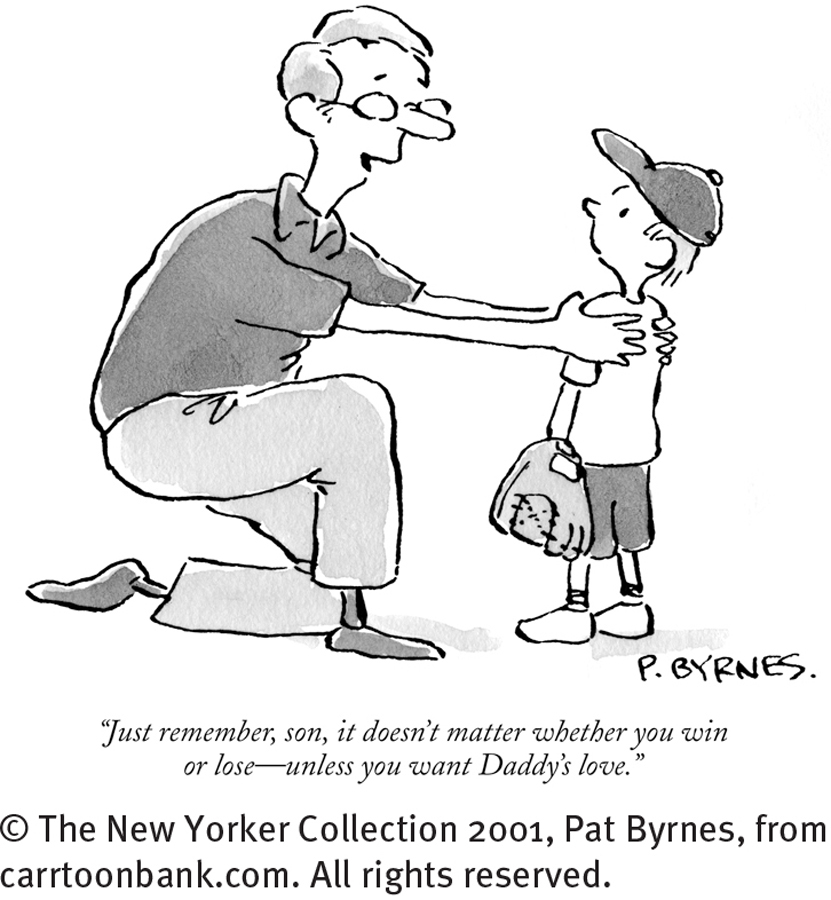

According to Carl Rogers, the road to dysfunction begins in infancy (Raskin, Rogers, & Witty, 2014; Rogers, 1987, 1951). We all have a basic need to receive positive regard from the important people in our lives (primarily our parents). Those who receive unconditional (nonjudgmental) positive regard early in life are likely to develop unconditional self-

Unfortunately, some children repeatedly are made to feel that they are not worthy of positive regard. As a result, they acquire conditions of worth, standards that tell them they are lovable and acceptable only when they conform to certain guidelines. To maintain positive self-

Rogers might view Philip Berman as a man who has gone astray. Rather than striving to fulfill his positive human potential, he drifts from job to job and relationship to relationship. In every interaction he is defending himself, trying to interpret events in ways he can live with, usually blaming his problems on other people. Nevertheless, his basic negative self-

Clinicians who practice Rogers’ client-

|

Client: |

Yes, I know I shouldn’t worry about it, but I do. Lots of things— |

|

Therapist: |

You feel that you’re pretty responsive to the opinions of other people. |

|

Client: |

Yes, but it’s things that shouldn’t worry me. |

|

Therapist: |

You feel that it’s the sort of thing that shouldn’t be upsetting, but they do get you pretty much worried anyway. |

|

Client: |

Just some of them. Most of those things do worry me because they’re true. The ones I told you, that is. But there are lots of little things that aren’t true…. Things just seem to be piling up, piling up inside of me…. It’s a feeling that things were crowding up and they were going to burst. |

|

Therapist: |

You feel that it’s a sort of oppression with some frustration and that things are just unmanageable. |

|

Client: |

In a way, but some things just seem illogical. I’m afraid I’m not very clear here but that’s the way it comes. |

|

Therapist: |

That’s all right. You say just what you think. |

|

(Snyder, 1947, pp. 2– |

|

In such an atmosphere, clients are expected to feel accepted by their therapists. They then may be able to look at themselves with honesty and acceptance. They begin to value their own emotions, thoughts, and behaviors, and so they are freed from the insecurities and doubts that prevent self-

Client-

Gestalt Theory and Therapy

Gestalt therapy, another humanistic approach, was developed in the 1950s by a charismatic clinician named Frederick (Fritz) Perls (1893–

gestalt therapy The humanistic therapy developed by Fritz Perls in which clinicians actively move clients toward self-

gestalt therapy The humanistic therapy developed by Fritz Perls in which clinicians actively move clients toward self-

In the technique of skillful frustration, gestalt therapists refuse to meet their clients’ expectations or demands. This use of frustration is meant to help people see how often they try to manipulate others into meeting their needs. In the technique of role playing, the therapists instruct clients to act out various roles. A person may be told to be another person, an object, an alternative self, or even a part of the body. Role playing can become intense, as individuals are encouraged to express emotions fully. Many cry out, scream, kick, or pound. Through this experience they may come to “own” (accept) feelings that previously made them uncomfortable.

Perls also developed a list of rules to ensure that clients will look at themselves more closely. In some versions of gestalt therapy, for example, clients may be required to use “I” language rather than “it” language. They must say, “I am frightened” rather than “The situation is frightening.” Yet another common rule requires clients to stay in the here and now. They have needs now, are hiding their needs now, and must observe them now.

Approximately 1 percent of clinical psychologists and other kinds of clinicians describe themselves as gestalt therapists (Prochaska & Norcross, 2013). Because they believe that subjective experiences and self-

Spiritual Views and Interventions

BETWEEN THE LINES

Charitable Acts

|

$308 billion |

Amount contributed to charities each year in the United States |

|

83% |

Percentage of Americans who have made charitable contributions in the last year |

|

33% |

Percentage of charitable donations contributed to religious organizations |

|

67% |

Percentage of donations directed to education, human services, health, and the arts |

|

(Information from: Gallup, 2013; American Association of Fundraising Counsel, 2010) |

|

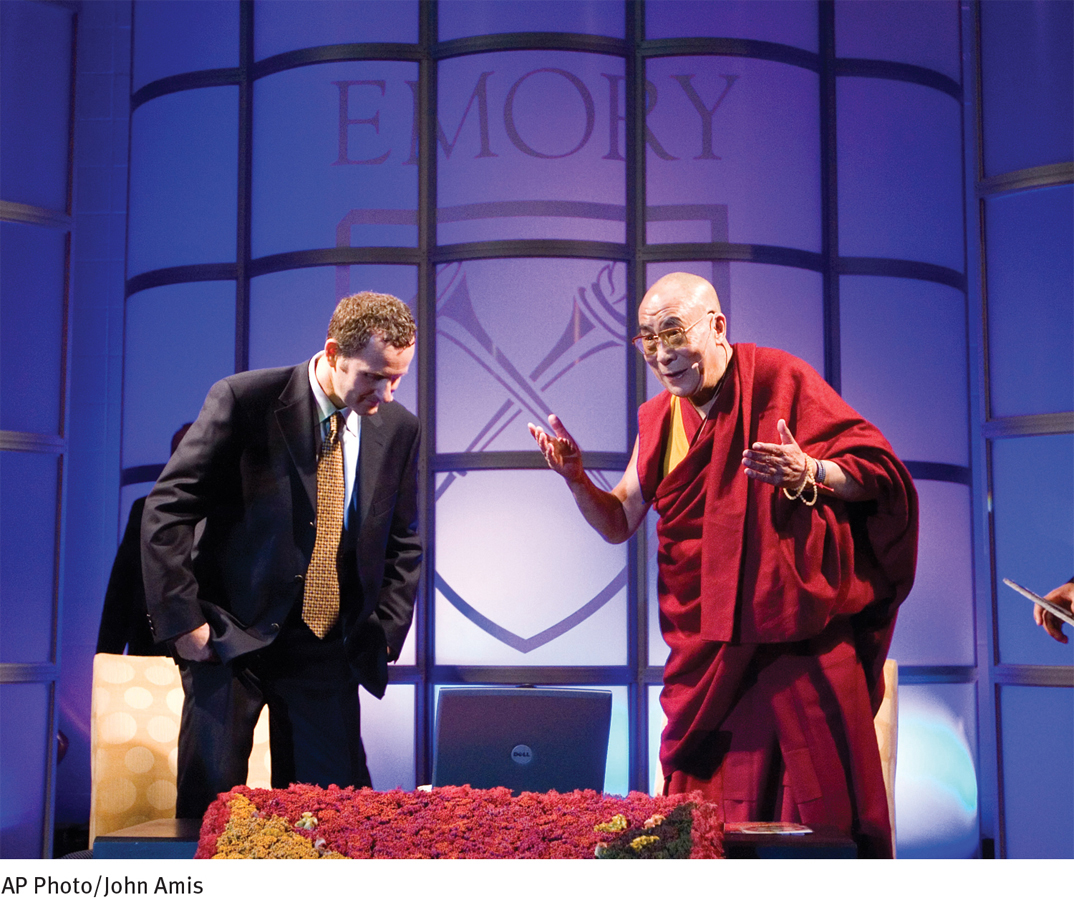

For most of the twentieth century, clinical scientists viewed religion as a negative—

Researchers have learned that spirituality does, in fact, often correlate with psychological health. In particular, studies have examined the mental health of people who are devout and who view God as warm, caring, helpful, and dependable. Repeatedly, these individuals are found to be less lonely, pessimistic, depressed, or anxious than people without any religious beliefs or those who view God as cold and unresponsive (Bonelli & Koenig, 2013; Day, 2010; Loewenthal, 2007). Such people also seem to cope better with major life stressors—

What various explanations might account for the correlation between spirituality and mental health?

Do such correlations indicate that spirituality helps produce greater mental health? Not necessarily. As you’ll recall from Chapter 2, correlations do not indicate causation. It may be, for example, that a sense of optimism leads to more spirituality, and that, independently, optimism contributes to greater mental health. Regardless of how the correlation between spirituality and mental health should be interpreted, many therapists now make a point of including spiritual issues when they treat religious clients (Brown, Elkonin, & Naiker, 2013; Worthington, 2011), and some further encourage clients to use their spiritual resources to help them cope with current stressors (Galanter, 2010). Similarly, a number of religious institutions offer counseling services to their members (see MediaSpeak below).

Existential Theories and Therapy

Like humanists, existentialists believe that psychological dysfunctioning is caused by self-

Existentialists might view Philip Berman as a man who feels overwhelmed by the forces of society. He sees his parents as “rich, powerful, and selfish,” and he perceives teachers, acquaintances, and employers as oppressing. He fails to appreciate his choices in life and his capacity for finding meaning and direction. Quitting becomes a habit with him—

In existential therapy, people are encouraged to accept responsibility for their lives and for their problems. Therapists try to help clients recognize their freedom so that they may choose a different course and live with greater meaning (Yalom, 2014; van Deurzen, 2012; Schneider & Krug, 2010). The precise techniques used in existential therapy vary from clinician to clinician. At the same time, most existential therapists place great emphasis on the relationship between therapist and client and try to create an atmosphere of honesty, hard work, and shared learning and growth.

existential therapy A therapy that encourages clients to accept responsibility for their lives and to live with greater meaning and value.

existential therapy A therapy that encourages clients to accept responsibility for their lives and to live with greater meaning and value.

MediaSpeak

Saving Minds Along With Souls

By T. M. Luhrmann, The New York Times, April 18, 2014

A few weeks ago, one year after his son took his life while struggling with depression, [Rick] Warren, the founding pastor of Saddleback Church, one of the nation’s largest evangelical churches, teamed up with his local Roman Catholic Diocese and the National Alliance on Mental Illness for an event that announced a new initiative to involve the church in the care of serious mental illness.

Their goal is not only to reduce stigma for people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression and the like, though that is an important part of it. “We are all broken,” Mr. Warren said in his remarks. … “We’re all a little bit mentally ill.”

The larger goal is to get the church directly involved with the care of people with serious psychiatric illness by training administrators and pastors to handle psychiatric crises, to set up groups within the church for people with serious mental illness and to establish services within the church for people who need them. These churches are not trying to supplant traditional mental health care. “When someone asks, Should I take medication or pray?” one speaker remarked, “I say, ‘yes.’” But they think that there aren’t enough services available for people who are really sick, and they think that many people don’t turn to them anyway because of the stigma. And so they think that there are a lot of people who aren’t getting the help they need.

They are right. The public mental health system is a woefully underfunded crazy-

But they do often go to church. More than 40 percent of Americans say that they attend church nearly every week. Even people who have nowhere to live often go to church.

In an urban Chicago neighborhood where I did many months of research with homeless psychotic women, I found that these women often refused psychiatric care. … But fully half of them said that they had a church and that they went to that church at least twice each month, and over 80 percent of them said that God was their best friend—

Mr. Warren’s initiative is remarkable for several reasons. Evangelical churches don’t go in much for hospital-

Even more remarkable is the initiative’s interest in training the ordinary people who work in church offices and hold prayer circles to be actively involved in mental health care. This can sound a little alarming. But in fact … a study just published in The Lancet demonstrated that this [kind of] community care [sometimes] produced modestly better outcomes for patients with schizophrenia than care in the psychiatric facility.

Might there be serious drawbacks to placing mental health care in the hands of strongly religious persons, even if they receive lay training?

… Psychiatrists are the least religious of all physicians, and the new initiative may leave them cold. But Mr. Warren has made an impact before: His initiative on H.I.V.-AIDS was partially responsible for generating George W. Bush’s President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. If this works, it could have a real impact on the mental health system.

We’re desperately in need of something that does.

(T. M. Luhrmann is a professor of anthropology at Stanford University and the author of When God Talks Back: Understanding the American Evangelical Relationship With God.)

April 19, 2014, “Contributing Op-

|

Patient: |

I don’t know why I keep coming here. All I do is tell you the same thing over and over. I’m not getting anywhere. |

|

Doctor: |

I’m getting tired of hearing the same thing over and over, too. |

|

Patient: |

Maybe I’ll stop coming. |

|

Doctor: |

It’s certainly your choice. |

|

Patient: |

What do you think I should do? |

|

Doctor: |

What do you want to do? |

|

Patient: |

I want to get better. |

|

Doctor: |

I don’t blame you. |

|

Patient: |

If you think I should stay, ok, I will. |

|

Doctor: |

You want me to tell you to stay? |

|

Patient: |

You know what’s best; you’re the doctor. |

|

Doctor: |

Do I act like a doctor? |

|

(Keen, 1970, p. 200) |

|

Existential therapists do not believe that experimental methods can adequately test the effectiveness of their treatments. To them, research dehumanizes individuals by reducing them to test measures. Not surprisingly, then, very little controlled research has been devoted to the effectiveness of this approach (Yalom, 2014; Schneider & Krug, 2010). Nevertheless, around 1 percent of today’s clinical psychologists use an approach that is primarily existential (Prochaska & Norcross, 2013).

Assessing the Humanistic-Existential Model

The humanistic-

The optimistic tone of the humanistic-

At the same time, the humanistic-