Chapter Introduction

| CHAPTER |

| 2 |

Research in Abnormal Psychology

TOPIC OVERVIEW

How Are Case Studies Helpful?

What Are the Limitations of Case Studies?

Describing a Correlation

When Can Correlations Be Trusted?

What Are the Merits of the Correlational Method?

Special Forms of Correlational Research

The Control Group

Random Assignment

Blind Design

Quasi-

Natural Experiments

Analogue Experiments

Single-

“Websites will never replace newspapers.”

Newsweek, 1995

“Next Christmas, the iPod will be dead, finished, gone, kaput.”

Amstrad (electronics company), 2005

“Guitar music is on the way out.”

Decca Recording Company, 1962

“There is no reason for any individual to have a computer in their home.”

Ken Olson, Digital Equipment Corp., 1977

“640K ought to be enough for anybody.”

Bill Gates, 1981

“Woman may be said to be an inferior man.”

Aristotle

“The cloning of mammals … is biologically impossible.”

James McGrath and Davor Solter, genetic researchers, 1984

“The ‘telephone’ has too many shortcomings to be seriously considered as a means of communication.”

Western Union, 1876

Can you think of beliefs that were once accepted as gospel but, as a result of scientific research, eventually were proven to be false?

Each of these statements was once accepted as gospel. Had their accuracy not been tested, had they been judged on the basis of conventional wisdom alone, had new ideas not been proposed and investigated, human knowledge and progress would have been severely limited. What enabled thinkers to move beyond such misperceptions? The answer, quite simply, is research, the systematic search for facts through the use of careful observations and investigations.

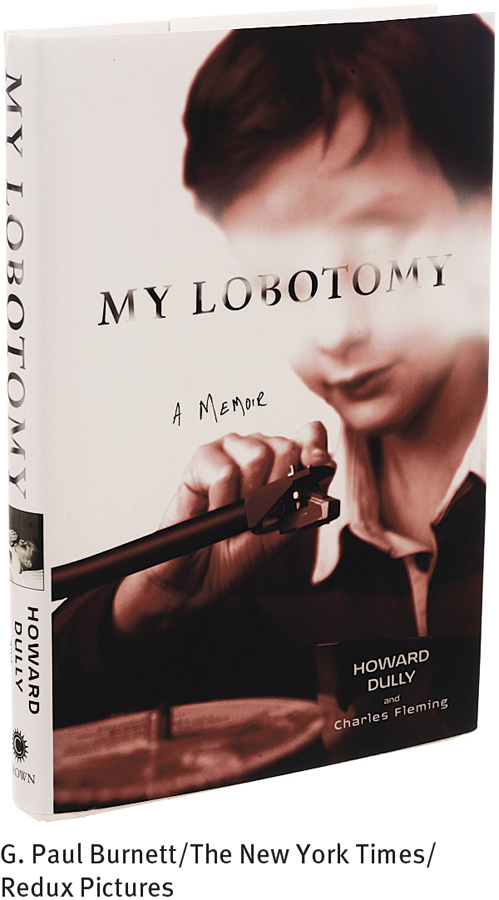

Research is the key to accuracy in all fields of study; it is particularly important in abnormal psychology because a wrong belief in this field can lead to great suffering. Consider, for example, schizophrenia and the treatment procedure known as the lobotomy. Schizophrenia is a severe disorder that causes people to lose contact with reality. Their thoughts, perceptions, and emotions become distorted and disorganized, and their behavior may be bizarre and withdrawn. For the first half of the twentieth century, this condition was attributed to poor parenting. Clinicians blamed schizophrenogenic (“schizophrenia-

During the same era, practitioners developed a surgical procedure that supposedly cured schizophrenia. In this procedure, called a lobotomy, a pointed instrument was inserted into the frontal lobe of the brain and rotated, destroying much brain tissue (Faria, 2013). Early clinical reports described lobotomized patients as showing near-

These errors underscore the importance of scientific research in abnormal psychology. Theories and treatments that seem effective in individual instances may prove disastrous to other people in different situations. Only by fully testing a theory or technique on representative groups of individuals can clinicians evaluate the accuracy, effectiveness, and safety of their ideas and techniques. Until clinical researchers conducted properly designed studies, millions of parents, already heartbroken by their children’s schizophrenia, were additionally labeled as the primary cause of the disorder, and countless people with schizophrenia, already debilitated by their symptoms, were made permanently apathetic and spiritless by a lobotomy.

Clinical researchers face certain challenges that make their work very difficult. They must, for example, figure out how to measure such elusive concepts as unconscious motives, private thoughts, mood changes, and human potential. They must consider the different cultural backgrounds, races, and genders of the people they choose to study. And, as we are reminded in PsychWatch in the next section, they must always ensure that the rights of their research participants, both human and animal, are not violated (Victor, 2013; Hobson-