4.2 Diagnosis: Does the Client’s Syndrome Match a Known Disorder?

Clinicians use the information from interviews, tests, and observations to construct an integrated picture of the factors that are causing and maintaining a client’s disturbance, a construction sometimes known as a clinical picture (Goldfinger & Pomerantz, 2014; Kellerman & Burry, 2007). Clinical pictures also may be influenced to a degree by the clinician’s theoretical orientation (Garb, 2010, 2006). The psychologist who worked with Franco held a cognitive-

Franco’s mother had reinforced his feelings of insecurity and his belief that he was unintelligent and inferior. When teachers tried to encourage and push Franco, his mother actually called him “an idiot.” Although he was the only one in his family to attend college and did well there, she told him he was too inadequate to succeed in the world. When he received a B in a college algebra course, his mother told him, “You’ll never have money.” She once told him, “You’re just like your father, dumb as a post,” and railed against, “the dumb men I got stuck with.”

As a child Franco had watched his parents argue. Between his mother’s self-

He took the termination of his relationship with Maria as proof that he was “stupid.” He felt foolish to have broken up with her. He interpreted his behavior and the break-

BETWEEN THE LINES

What Is a Nervous Breakdown?

The term “nervous breakdown” is used by laypersons, not clinicians. Most people use it to refer to a sudden psychological disturbance that incapacitates a person, perhaps requiring hospitalization. Some people use the term simply to connote the onset of any psychological disorder (Hall-

With the assessment data and clinical picture in hand, clinicians are ready to make a diagnosis (from the Greek word for “a discrimination”)—that is, a determination that a person’s psychological problems constitute a particular disorder. When clinicians decide, through diagnosis, that a client’s pattern of dysfunction reflects a particular disorder, they are saying that the pattern is basically the same as one that has been displayed by many other people, has been investigated in a variety of studies, and perhaps has responded to particular forms of treatment. They can then apply what is generally known about the disorder to the particular individual they are trying to help. They can, for example, better predict the future course of the person’s problem and the treatments that are likely to be helpful.

diagnosis A determination that a person’s problems reflect a particular disorder.

diagnosis A determination that a person’s problems reflect a particular disorder.

Classification Systems

The principle behind diagnosis is straightforward. When certain symptoms occur together regularly—

syndrome A cluster of symptoms that usually occur together.

syndrome A cluster of symptoms that usually occur together.

classification system A list of disorders, along with descriptions of symptoms and guidelines for making appropriate diagnoses.

classification system A list of disorders, along with descriptions of symptoms and guidelines for making appropriate diagnoses.

|

January |

Mental Wellness Month |

|

March |

Developmental Disabilities Awareness Month |

|

April |

Alcohol Awareness Month |

|

May |

Children’s Mental Health Awareness Week |

|

June |

Panic Awareness Day (June 17) Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Awareness Day (June 27) |

|

September |

World Suicide Prevention Day (September 10) |

|

October |

National Depression Awareness Month World Mental Health Day (October 10) National Bipolar Awareness Day (October 10) OCD Awareness Week ADHD Awareness Month |

|

November |

National Alzheimer’s Disease Awareness Month |

|

Information from: Disabled World, 2014. |

|

In 1883, Emil Kraepelin developed the first modern classification system for abnormal behavior (see Chapter 1). His categories formed the foundation for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the classification system currently written by the American Psychiatric Association (APA, 2013). The DSM is the most widely used classification system in North America. Most other countries rely primarily on a system called the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), developed by the World Health Organization, which lists both medical and psychological disorders. Although there are a number of differences between the disorders listed in the DSM and ICD and in their descriptions of criteria for various disorders (the DSM’s descriptions are more detailed), the federal government has required that by the end of 2014, the numerical codes used by the DSM for all disorders must match those used by the ICD—

Why do you think many clinicians prefer the label “person with schizophrenia” over “schizophrenic person”?

The content of the DSM has been changed significantly over time. The current edition, called DSM-

DSM-5

DSM-

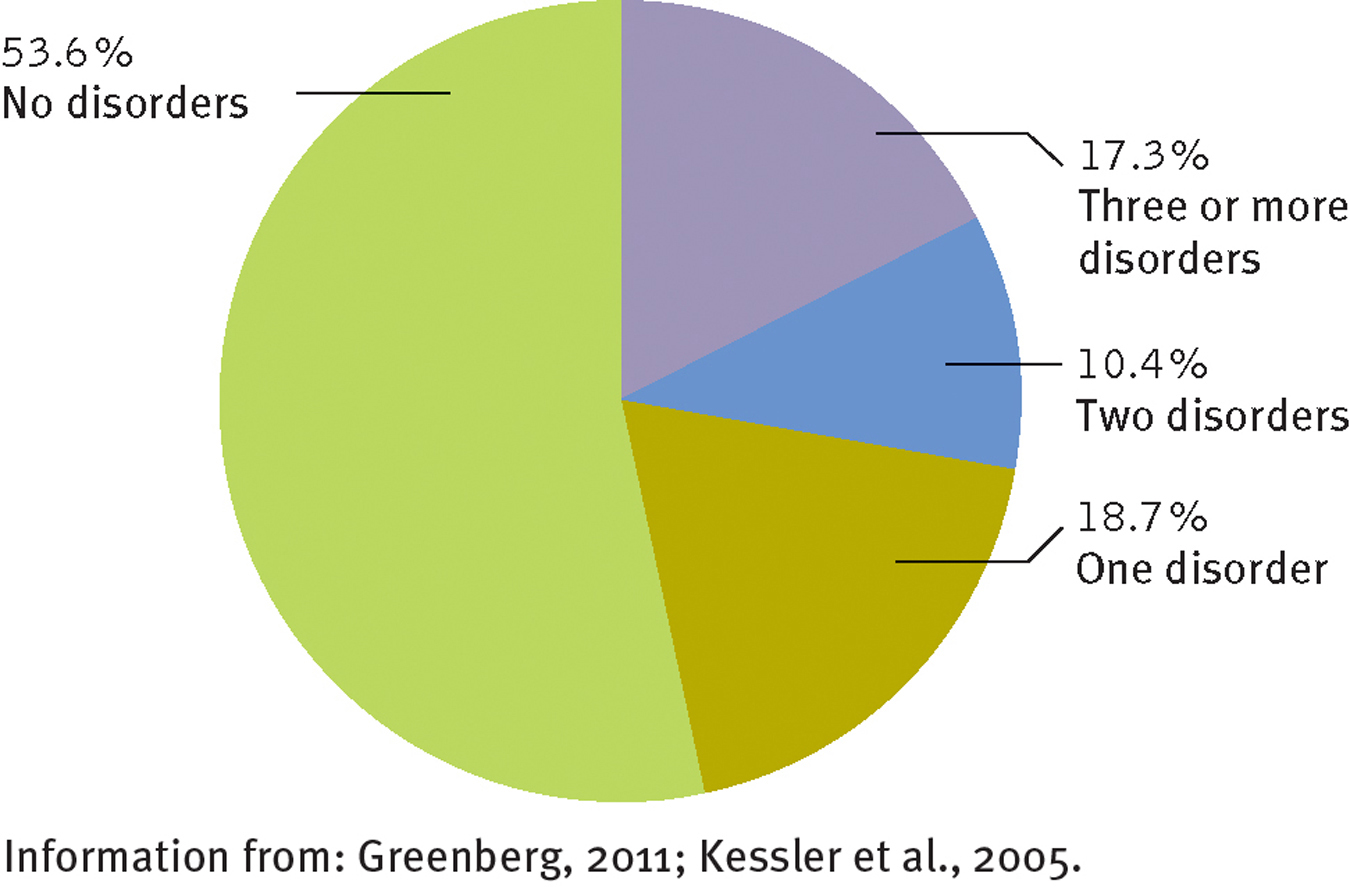

How many people in the United States qualify for a DSM diagnosis during their lives? Almost half, according to some surveys. Some people even experience two or more different disorders, which is known as comorbidity.

DSM-

Categorical InformationFirst, the clinician must decide whether the person is displaying one of the hundreds of psychological disorders listed in the manual. Some of the most frequently diagnosed disorders are the anxiety disorders and depressive disorders.

ANXIETY DISORDERSPeople with anxiety disorders may experience general feelings of anxiety and worry (generalized anxiety disorder); fears of specific situations, objects, or activities (phobias); anxiety about social situations (social anxiety disorder); repeated outbreaks of panic (panic disorder); or anxiety about being separated from one’s parents or other key individuals (separation anxiety disorder).

DEPRESSIVE DISORDERSPeople with depressive disorders may experience an episode of extreme sadness and related symptoms (major depressive disorder), persistent and chronic sadness (persistent depressive disorder), or severe premenstrual sadness and related symptoms (premenstrual dysphoric disorder).

Although people may receive just one diagnosis from the DSM-

Dimensional InformationIn addition to deciding what disorder a client is displaying, diagnosticians assess the current severity of the client’s disorder—

PsychWatch

Culture-

Red Bear sits up wild-

Suddenly, the form of Red Bear’s sleeping wife begins to change. He no longer sees a woman, but a deer …

With the body of the “deer” at his feet, Red Bear raises the knife high, preparing the strike … [T]he knife flashes down, again and again.

(LindhoLm & LindhoLm, 1981, p. 52)

Red Bear was suffering from windigo, a disorder once common among Algonquin Indian hunters. They believed in a supernatural monster that ate human beings and had the power to bewitch them and turn them into cannibals. Red Bear was among the few afflicted hunters who actually did kill and eat members of their households.

Windigo is but one of numerous unusual mental disorders discovered around the world, each unique to a particular culture, each apparently growing from that culture’s pressures, history, institutions, and ideas (Durà-Vilà & Hodes, 2012; Flaskerud, 2009; Draguns, 2006). Such disorders remind us that the classifications and diagnoses applied in one culture may not always be appropriate in another.

The symptoms of susto, a disorder found among members of Indian tribes in Central and South America and native peoples of the Andean highlands of Peru, Bolivia, and Colombia are extreme anxiety, excitability, and depression, along with loss of weight, weakness, and rapid heartbeat. The culture holds that this disorder is caused by contact with supernatural beings or with frightening strangers or by bad air from cemeteries.

People affected with amok, a disorder found in Malaysia, the Philippines, Java, and some parts of Africa, jump around violently, yell loudly, grab knives or other weapons, and attack any people and objects they encounter. Within the culture, amok is thought to be caused by stress, severe shortage of sleep, alcohol consumption, and extreme heat.

Koro is a pattern of anxiety found in Southeast Asia in which a man suddenly becomes intensely fearful that his penis will withdraw into his abdomen and that he will die as a result. Cultural lore holds that the disorder is caused by an imbalance of “yin” and “yang,” two natural forces believed to be the fundamental components of life. Accepted forms of treatment include having the individual keep a firm hold on his penis until the fear passes, often with the assistance of family members or friends, and clamping the penis to a wooden box.

Additional InformationClinicians also may include other useful information when making a diagnosis. They may, for example, indicate special psychosocial problems the client has. Franco’s recent breakup with his girlfriend might be noted as relationship distress. Altogether, Franco might receive the following diagnosis:

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

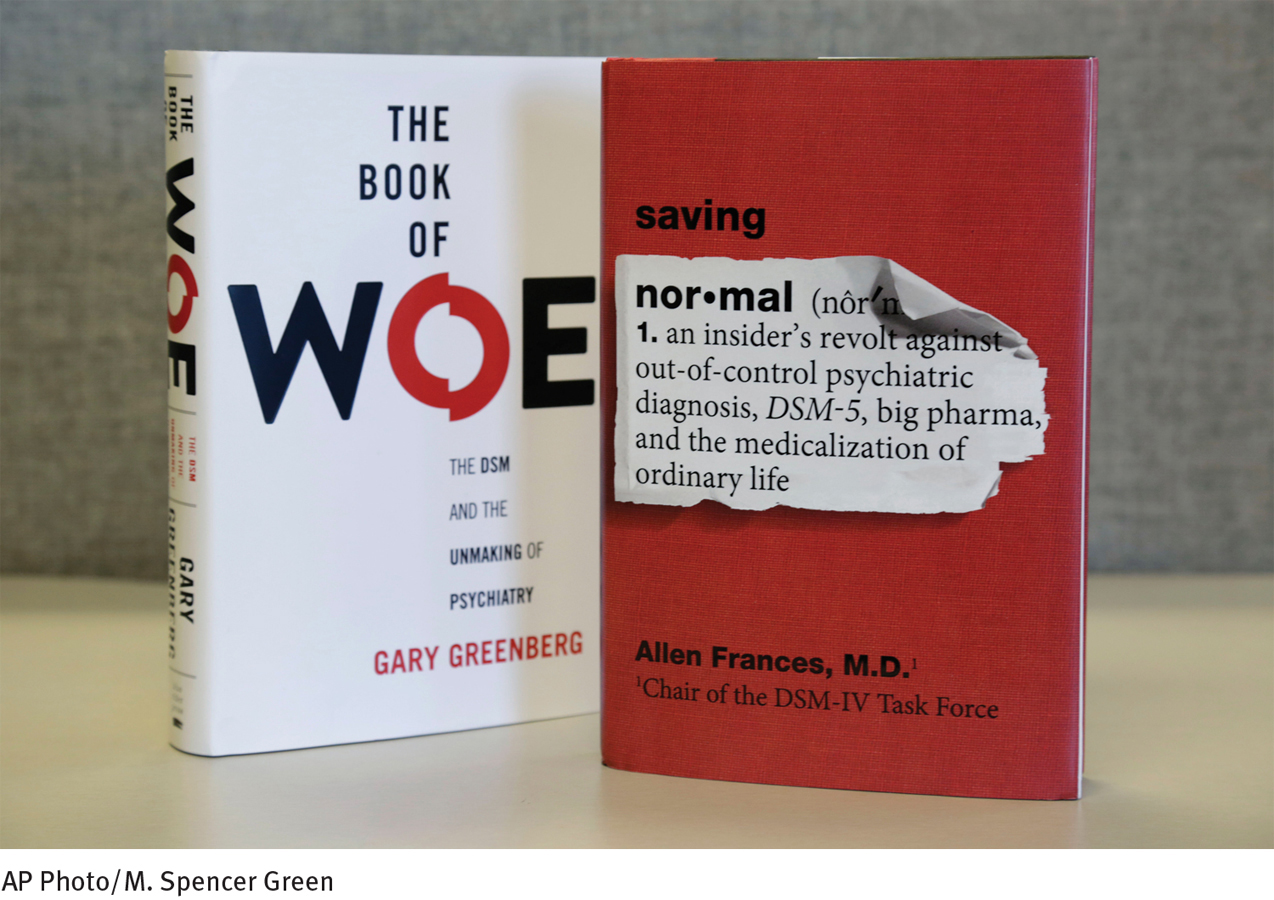

“The boundary of psychiatry keeps expanding; the realm of normal is shrinking…. As chairman of the DSM-

Allen Frances, 2013 Chair of the DSM-

Diagnosis: Major depressive disorder with anxious distress

Severity: Moderate

Additional information: Relationship distress

Is DSM-5 an Effective Classification System?

A classification system, like an assessment method, is judged by its reliability and validity. Here reliability means that different clinicians are likely to agree on the diagnosis when they use the system to diagnose the same client. Early versions of the DSM were at best moderately reliable (Regier et al., 2011; Malik & Beutler, 2002). In the early 1960s, for example, four clinicians, each relying on DSM-

The framers of DSM-

The validity of a classification system is the accuracy of the information that its diagnostic categories provide. Categories are of most use to clinicians when they demonstrate predictive validity—that is, when they help predict future symptoms or events. A common symptom of major depressive disorder is either insomnia or excessive sleep. When clinicians give Franco a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, they expect that he may eventually develop sleep problems even if none are present now. In addition, they expect him to respond to treatments that are effective for other depressed persons. The more often such predictions are accurate, the greater a category’s predictive validity.

BETWEEN THE LINES

By the Numbers

|

1 |

Number of categories of psychological dysfunctioning listed in the 1840 U.S. census (“idiocy/insanity”) |

|

7 |

Number of categories listed in the 1880 census |

|

60 |

Number of categories listed in DSM- |

|

400 |

Number of categories listed in DSM- |

DSM-

Actually, one important organization, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), has already concluded that the validity of DSM-

Call for Change

The effort to produce DSM-

BETWEEN THE LINES

New Pop Psychology Labels

“Online disinhibition effect” The tendency of people to show less restraint when on the Internet (Sitt, 2013; Suler, 2004).

“Drunkorexia” A diet fad, particularly among young women, in which the individual restricts food intake during the day so that she can party and get drunk at night without gaining weight from the alcohol (Archer, 2013).

BETWEEN THE LINES

Cutting Financial Ties

Before being appointed to the DSM-

Between 2010 and 2012, the task force released several drafts of DSM-

Some of the key changes in DSM-

Adding a new category, “autism spectrum disorder,” that combines certain past categories such as “autistic disorder” and “Asperger’s syndrome” (see Chapter 17).

Viewing “obsessive-

compulsive disorder” as a problem that is different from the anxiety disorders and grouping it instead along with other obsessive- compulsive- like disorders such as “hoarding disorder,” “body dysmorphic disorder,” “trichotillomania” (hair- pulling disorder), and “excoriation (skin- picking) disorder” (see Chapter 5). Viewing “posttraumatic stress disorder” as a problem that is distinct from the anxiety disorders (see Chapter 6).

Adding new categories, “disruptive mood dysregulation disorder,” “persistent depressive disorder,” and “premenstrual dysphoric disorder,” and grouping them with other kinds of depressive disorders (see Chapter 7).

Adding a new category, “somatic symptom disorder” (see Chapter 10).

Page 119Replacing the term “hypochondriasis” with the new term “illness anxiety disorder” (see Chapter 10).

Adding a new category, “binge eating disorder” (see Chapter 11).

Adding a new category, “substance use disorder,” that combines past categories “substance abuse” and “substance dependence” (see Chapter 12).

Viewing “gambling disorder” as a problem that should be grouped as an addictive disorder alongside the substance use disorders (see Chapter 12).

Replacing the term “gender identity disorder” with the new term “gender dysphoria” (see Chapter 13).

Replacing the term “mental retardation” with the new term “intellectual disability” (see Chapter 17).

Adding a new category, “specific learning disorder,” that combines past categories “reading disorder,” “mathematics disorder,” and “disorder of written expression” (see Chapter 17).

Replacing the term “dementia” with the new term “neurocognitive disorder” (see Chapter 18).

Adding a new category, “mild neurocognitive disorder” (see Chapter 18).

Can Diagnosis and Labeling Cause Harm?

Even with trustworthy assessment data and reliable and valid classification categories, clinicians will sometimes arrive at a wrong conclusion (Faust & Ahern, 2012; Trull & Prinstein, 2012). Like all human beings, they are flawed information processors. Studies show that they are overly influenced by information gathered early in the assessment process (Dawes, Faust, & Meehl, 2002; Meehl, 1996, 1960). They sometimes pay too much attention to certain sources of information, such as a parent’s report about a child, and too little to others, such as the child’s point of view (McCoy, 1976). Finally, their judgments can be distorted by any number of personal biases—

In a classic study, for example, a clinical team was asked to reevaluate the records of 131 patients at a mental hospital in New York, conduct interviews with many of these persons, and arrive at a diagnosis for each one (Lipton & Simon, 1985). The researchers then compared the team’s diagnoses with the original diagnoses for which the patients were hospitalized. Although 89 of the patients had originally received a diagnosis of schizophrenia, only 16 received it upon reevaluation. And whereas 15 patients originally had been given a diagnosis of a mood disorder, 50 received it now. It is obviously important for clinicians to be aware that such huge disagreements can occur.

Why are medical diagnoses usually valued, while the use of psychological diagnoses is often criticized?

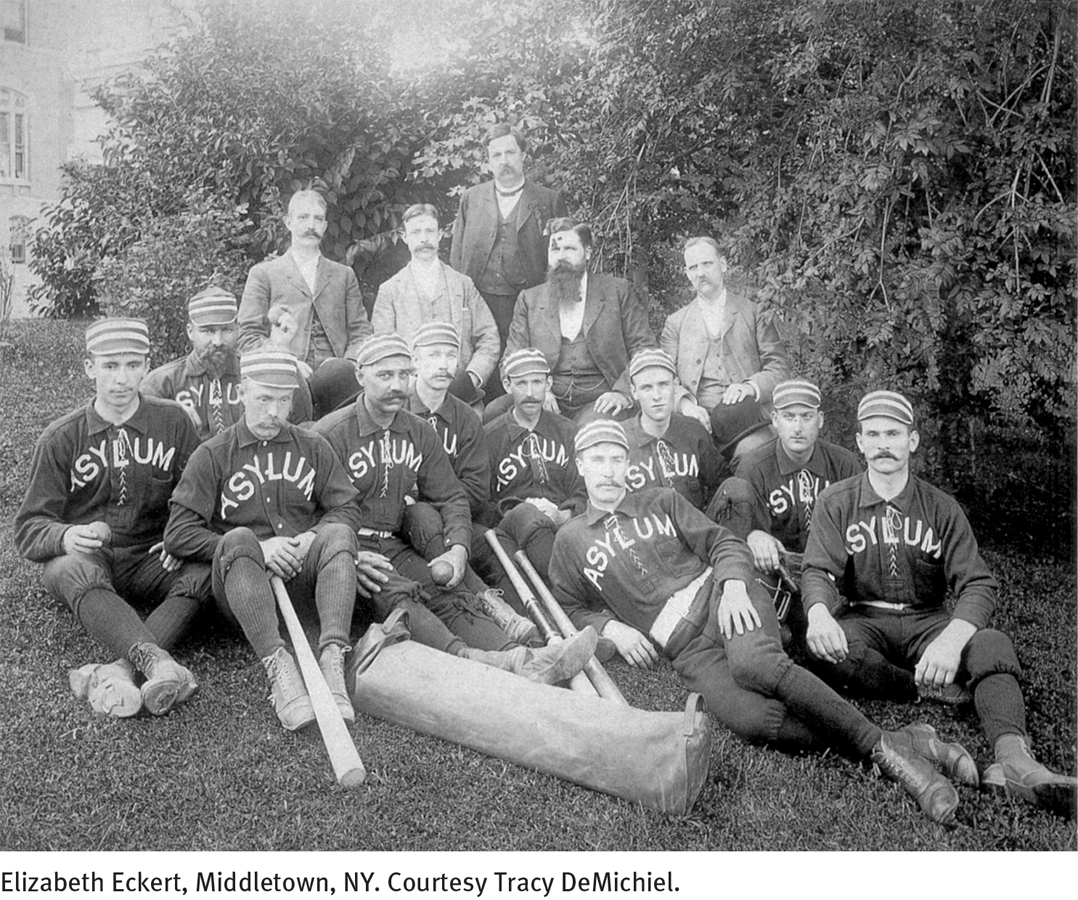

Beyond the potential for misdiagnosis, the very act of classifying people can lead to unintended results. As you read in Chapter 3, for example, many family-

Because of these problems, some clinicians would like to do away with diagnoses. Others disagree. They believe we must simply work to increase what is known about psychological disorders and improve diagnostic techniques. They hold that classification and diagnosis are critical to understanding and treating people in distress.