5.1 Generalized Anxiety Disorder

People with generalized anxiety disorder experience excessive anxiety under most circumstances and worry about practically anything. In fact, their problem is sometimes described as free-

generalized anxiety disorder A disorder marked by persistent and excessive feelings of anxiety and worry about numerous events and activities.

generalized anxiety disorder A disorder marked by persistent and excessive feelings of anxiety and worry about numerous events and activities.

|

Generalized Anxiety Disorder |

|

|---|---|

|

1. |

For 6 months or more, person experiences disproportionate, uncontrollable, and ongoing anxiety and worry about multiple matters. |

|

2. |

The symptoms include at least three of the following: edginess, fatigue, poor concentration, irritability, muscle tension, sleep problems. |

|

3. |

Significant distress or impairment. |

|

Information from: APA, 2013. |

|

Generalized anxiety disorder is common in Western society. Surveys suggest that as much as 4 percent of the U.S. population has the symptoms of this disorder in any given year, a rate that holds across Canada, Britain, and other Western countries (Kessler et al., 2012, 2010, 2005; Ritter, Blackmore, & Heimberg, 2010). Altogether, more than 6 percent of all people develop generalized anxiety disorder sometime during their lives. It may emerge at any age, but usually it first appears in childhood or adolescence. Women diagnosed with the disorder outnumber men 2 to 1. Around one-

A variety of factors have been cited to explain the development of this disorder. Here you will read about the views and treatments offered by the sociocultural, psychodynamic, humanistic, cognitive, and biological models. We will examine the behavioral perspective when we turn to phobias later in the chapter because that model approaches generalized anxiety disorder and phobias in basically the same way.

The Sociocultural Perspective: Societal and Multicultural Factors

According to sociocultural theorists, generalized anxiety disorder is most likely to develop in people who are faced with ongoing societal conditions that are dangerous. Studies have found that people in highly threatening environments are indeed more likely to develop the general feelings of tension, anxiety, and fatigue and the sleep disturbances found in this disorder (Slopen et al., 2012; Stein & Williams, 2010).

Take, for example, a classic study that was done on the psychological impact of living near the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant after the nuclear reactor accident of March 1979 (Baum et al., 2004; Wroble & Baum, 2002). In the months following the accident, local mothers of preschool children were found to display five times as many anxiety or depression disorders as mothers living elsewhere. Although the number of disorders decreased during the next year, the Three Mile Island mothers still displayed high levels of anxiety or depression a year later. Similarly, studies conducted more recently have found that in the months and years following Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the Haitian earthquake in 2010, the rate of generalized and other anxiety disorders was twice as high among area residents who lived through the disasters as among unaffected persons living elsewhere (Shultz et al., 2012; Galea et al., 2007).

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“Neither a man nor a crowd nor a nation can be trusted to act humanely or to think sanely under the influence of a great fear.”

Bertrand Russell

One of the most powerful forms of societal stress is poverty. People without financial means are likely to live in rundown communities with high crime rates, have fewer educational and job opportunities, and run a greater risk for health problems (Moore, Radcliffe, & Liu, 2014; López & Guarnaccia, 2008, 2005, 2000). As sociocultural theorists would predict, such people also have a higher rate of generalized anxiety disorder (McLaughlin et al., 2012; Stein & Williams, 2010). In the United States, the rate is almost twice as high among people with low incomes as among those with higher incomes (Sareen et al., 2011; Kessler et al., 2010, 2005). As wages decrease, the rate of generalized anxiety disorder steadily increases (see Table 5-2).

|

Prevalence of Anxiety Disorders and Obsessive- |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Female |

Low Income |

African American |

Hispanic American |

Elderly |

|

Generalized anxiety disorder |

Higher |

Higher |

Higher |

Same |

Higher |

|

Specific phobias |

Higher |

Higher |

Higher |

Higher |

Lower |

|

Agoraphobia |

Higher |

Higher |

Same |

Same |

Higher |

|

Social anxiety disorder |

Higher |

Higher |

Higher |

Lower |

Lower |

|

Panic disorder |

Higher |

Higher |

Same |

Same |

Lower |

|

Obsessive- |

Same |

Higher |

Same |

Same |

Lower |

|

Information from: Polo et al., 2011; Sareen et al., 2011; Bharani & Lantz, 2008; Hopko et al., 2008; Nazarian & Craske, 2008; Schultz et al., 2008. |

|||||

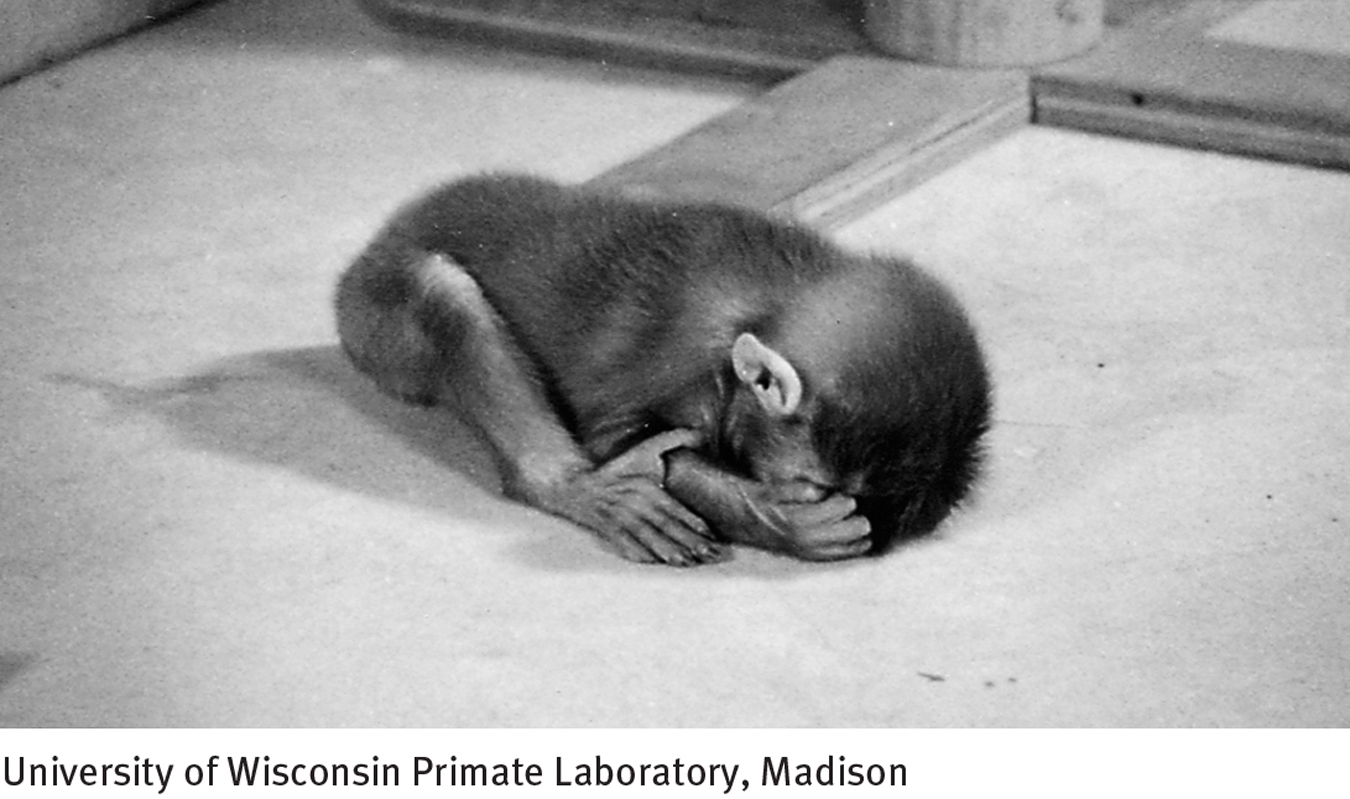

Since race is closely tied to stress in the United States (related to discrimination, low income, and reduced job opportunities), it is not surprising that it too is sometimes tied to the prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder (Sibrava et al., 2013; Marques et al., 2011; Soto et al., 2011). In any given year, African Americans are 30 percent more likely than white Americans to suffer from this disorder. Moreover, although researchers have not consistently found a heightened rate of generalized anxiety disorder among Hispanic Americans, they have noted that many Hispanics in both the United States and Latin American suffer from nervios (“nerves”), a culture-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Insecurity, Adult Style

Children may cling to blankets or cuddly toys to feel more secure. Adults, too, may hug a beloved object in order to relax: 1 in 5 women and 1 in 20 men admit to sleeping with a stuffed animal on a regular basis (Kanner, 1995).

Although poverty and various societal and cultural pressures may help create a climate in which generalized anxiety disorder is more likely to develop, socio-

The Psychodynamic Perspective

Sigmund Freud (1933, 1917) believed that all children experience some degree of anxiety as part of growing up and that all use ego defense mechanisms to help control such anxiety (see pages 63–

Psychodynamic Explanations: When Childhood Anxiety Goes UnresolvedAccording to Freud, when a child is overrun by neurotic or moral anxiety, the stage is set for generalized anxiety disorder. Early developmental experiences may produce an unusually high level of anxiety in such a child. Say that a boy is spanked every time he cries for milk as an infant, messes his pants as a 2-

Alternatively, a child’s ego defense mechanisms may be too weak to cope with even normal levels of anxiety. Overprotected children, shielded by their parents from all frustrations and threats, have little opportunity to develop effective defense mechanisms. When they face the pressures of adult life, their defense mechanisms may be too weak to cope with the resulting anxieties.

Today’s psychodynamic theorists often disagree with specific aspects of Freud’s explanation for generalized anxiety disorder. Most continue to believe, however, that the disorder can be traced to inadequacies in the early relationships between children and their parents (Sharf, 2012). Researchers have tested the psychodynamic explanations in various ways. In one strategy, they have tried to show that people with generalized anxiety disorder are particularly likely to use defense mechanisms. For example, one team of investigators examined the early therapy transcripts of patients with this diagnosis and found that the patients often reacted defensively. When asked by therapists to discuss upsetting experiences, they would quickly forget (repress) what they had just been talking about, change the direction of the discussion, or deny having negative feelings (Luborsky, 1973).

In another line of research, investigators have studied people who as children suffered extreme punishment for id impulses. As psychodynamic theorists would predict, these people have higher levels of anxiety later in life (Busch, Milrod, & Shear, 2010; Chiu, 1971). In addition, several studies have supported the psychodynamic position that extreme protectiveness by parents may often lead to high levels of anxiety in their children (Manfredi et al., 2011; Jenkins, 1968).

BETWEEN THE LINES

Google’s Most Searched Symptoms

Pregnancy symptoms

Influenza symptoms

Diabetes symptoms

Anxiety symptoms

Thyroid symptoms

(Sifferlin, 2013)

Although these studies are consistent with psychodynamic explanations, some scientists question whether they show what they claim to show. When people have difficulty talking about upsetting events early in therapy, for example, they are not necessarily repressing those events. They may be focusing purposely on the positive aspects of their lives, or they may be too embarrassed to share personal negative events until they develop trust in the therapist.

Psychodynamic TherapiesPsychodynamic therapists use the same general techniques to treat all psychological problems: free association and the therapist’s interpretations of transference, resistance, and dreams. Freudian psychodynamic therapists use these methods to help clients with generalized anxiety disorder become less afraid of their id impulses and more successful in controlling them. Other psychodynamic therapists, particularly object relations therapists, use them to help anxious patients identify and settle the childhood relationship problems that continue to produce anxiety in adulthood (Lucas, 2006).

Controlled studies have typically found psychodynamic treatments to be of only modest help to persons with generalized anxiety disorder (Craske, 2010). An exception to this trend is short-

The Humanistic Perspective

Humanistic theorists propose that generalized anxiety disorder, like other psychological disorders, arises when people stop looking at themselves honestly and acceptingly. Repeated denials of their true thoughts, emotions, and behavior make these people extremely anxious and unable to fulfill their potential as human beings.

The humanistic view of why people develop this disorder is best illustrated by Carl Rogers’ explanation. As you saw in Chapter 3, Rogers believed that children who fail to receive unconditional positive regard from others may become overly critical of themselves and develop harsh self-

Practitioners of Rogers’s treatment approach, client-centered therapy (also called person-

client-centered therapy The humanistic therapy developed by Carl Rogers in which clinicians try to help clients by being accepting, empathizing accurately, and conveying genuineness. Also known as person-

client-centered therapy The humanistic therapy developed by Carl Rogers in which clinicians try to help clients by being accepting, empathizing accurately, and conveying genuineness. Also known as person-

Therapy was an experiencing of her self, in all its aspects, in a safe relationship … the experiencing of self as having a capacity for wholeness … a self that cared about others. This last followed … the realization that the therapist cared, that it really mattered to him how therapy turned out for her, that he really valued her…. She gradually became aware of the fact that … there was nothing fundamentally bad, but rather, at heart she was positive and sound.

(Rogers, 1954, pp. 261–

Despite such optimistic case reports, controlled studies have failed to offer strong support for this approach. Although research does suggest that client-

The Cognitive Perspective

Followers of the cognitive model suggest that psychological problems are often caused by dysfunctional ways of thinking (see PsychWatch below). Given that excessive worry—

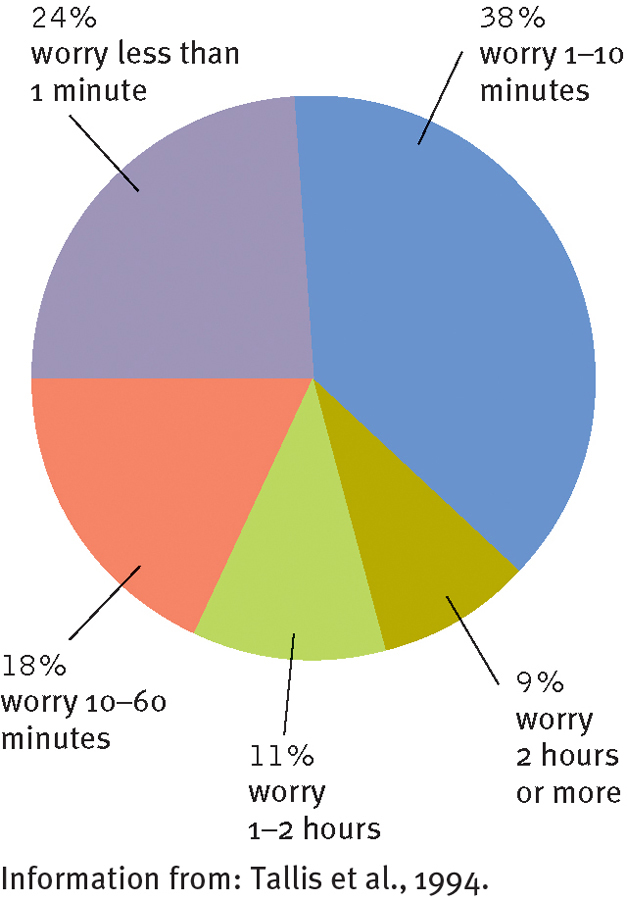

How long do your worries last?

In one survey, 62 percent of college students said they spend less than 10 minutes at a time worrying about something. In contrast, 20 percent worry for more than an hour.

Maladaptive AssumptionsInitially, cognitive theorists suggested that generalized anxiety disorder is primarily caused by maladaptive assumptions, a notion that continues to be influential. Albert Ellis, for example, proposed that many people are guided by irrational beliefs that lead them to act and react in inappropriate ways (Ellis, 2014, 2002, 1962). Ellis called these basic irrational assumptions, and he claimed that people with generalized anxiety disorder often hold the following ones:

basic irrational assumptions The inaccurate and inappropriate beliefs held by people with various psychological problems, according to Albert Ellis.

basic irrational assumptions The inaccurate and inappropriate beliefs held by people with various psychological problems, according to Albert Ellis.

“It is a dire necessity for an adult human being to be loved or approved of by virtually every significant other person in his community.”

“It is awful and catastrophic when things are not the way one would very much like them to be.”

“If something is or may be dangerous or fearsome, one should be terribly concerned about it and should keep dwelling on the possibility of its occurring.”

“One should be thoroughly competent, adequate, and achieving in all possible respects if one is to consider oneself worthwhile.”

(Ellis, 1962)

When people who make these assumptions are faced with a stressful event, such as an exam or a first date, they are likely to interpret it as dangerous, to overreact, and to feel fear. As they apply the assumptions to more and more events, they may begin to develop generalized anxiety disorder.

Similarly, cognitive theorist Aaron Beck argued that people with generalized anxiety disorder constantly hold silent assumptions (for example, “A situation or a person is unsafe until proven to be safe” or “It is always best to assume the worst”) that imply they are in imminent danger (Clark & Beck, 2012, 2010; Beck & Emery, 1985). Since the time of Ellis’ and Beck’s initial proposals, researchers have repeatedly found that people with generalized anxiety disorder do indeed hold maladaptive assumptions, particularly about dangerousness (Clark & Beck, 2012, 2010; Ferreri et al., 2011).

New-

Why might many people believe, at least implicitly, that worrying is useful—

The metacognitive theory, developed by the researcher Adrian Wells (2014, 2011, 2005), suggests that people with generalized anxiety disorder implicitly hold both positive and negative beliefs about worrying. On the positive side, they believe that worrying is a useful way of appraising and coping with threats in life. And so they look for and examine all possible signs of danger—

PsychWatch

Fears, Shmears: The Odds Are Usually on Our Side

People with anxiety disorders have many unreasonable fears, but millions of other people, too, worry about disaster every day. Most of the catastrophes they fear are not probable. Perhaps the ability to live by laws of probability rather than possibility is what separates the fearless from the fearful. What are the odds, then, that commonly feared events will happen? The range of probability is wide, but the odds are usually heavily in our favor.

A city resident will be a victim of a violent crime: 1 in 237

A suburbanite will be a victim of a violent crime: 1 in 408

A child will suffer a high-

The IRS will audit you this year: 1 in 100

You will be murdered this year: 1 in 20,000

You will be a victim of burglary this year: 1 in 35

You will be a victim of robbery this year: 1 in 885

You will be killed on your next bus ride: 1 in 500 million

You will be hit by a baseball at a major-

You will drown in the tub this year: 1 in 685,000

Your house will have a fire this year: 1 in 200

Your carton will contain a broken egg: 1 in 10

You will develop a tooth cavity: 1 in 6

You will contract AIDS from a blood transfusion: 1 in 286,000

You will die in a tsunami: 1 in 500,000

You will be attacked by a shark: 1 in 4 million

You will receive a diagnosis of cancer this year: 1 in 8,000

A woman will develop breast cancer during her lifetime: 1 in 8

A piano player will eventually develop lower back pain: 1 in 3

You will be killed on your next automobile outing: 1 in 4 million

Condom use will eventually fail to prevent pregnancy: 1 in 8

An IUD will eventually fail to prevent pregnancy: 1 in 167

Coitus interruptus will eventually fail to prevent pregnancy: 1 in 5

You will die as a result of a lightning strike: 1 in 10 million

(INFORMATION FROM: FBI, 2014; GLOVIN, 2014; CDC, 2013; QUILLIAN & PAGER, 2012; BRITT, 2005)

At the same time, Wells argues, people with generalized anxiety disorder also hold negative beliefs about worrying, and these negative attitudes are the ones that open the door to the disorder. Because society teaches them that worrying is a bad thing, they come to believe that their repeated worrying is in fact harmful (mentally and physically) and uncontrollable. Now they further worry about the fact that they always seem to be worrying (so-

|

I am going crazy with worry. |

|

My worrying will escalate and I’ll cease to function. |

|

I’m making myself ill with worry. |

|

I’m abnormal for worrying. |

|

My mind can’t take the worrying. |

|

I’m losing out in life because of worrying. |

|

My body can’t take the worrying. |

|

Information from: Wells, 2011, 2010, 2005. |

This explanation has received considerable research support. Studies indicate, for example, that people who generally hold both positive and negative beliefs about worrying are particularly prone to developing generalized anxiety disorder and that repeated metaworrying is a powerful predictor of developing the disorder (Wells, 2014, 2011, 2005; Ferreri et al., 2011).

According to another new explanation for generalized anxiety disorder, the intolerance of uncertainty theory, certain individuals cannot tolerate the knowledge that negative events may occur, even if the possibility of occurrence is very small. Inasmuch as life is filled with uncertain events, these individuals worry constantly that such events are about to occur. Such intolerance and worrying leave them highly vulnerable to the development of generalized anxiety disorder (Dugas et al., 2012, 2010, 2004; Fisher & Wells, 2011). Think of when you meet someone you’re attracted to and how you then feel prior to texting or calling call him or her for the first time—

Proponents of this theory believe people with generalized anxiety disorder keep worrying and worrying in their efforts to find “correct” solutions for various situations in their lives and to restore certainty to the situations. However, because they can never really be sure that a given solution is a correct one, they are always left to grapple with intolerable levels of uncertainty, triggering new rounds of worrying and new efforts to find correct solutions. Like the metacognitive theory of worry, considerable research supports this theory. Studies have found, for example, that people with generalized anxiety disorder display higher levels of intolerance of uncertainty than people with normal degrees of anxiety (Dugas et al., 2012, 2010, 2009, 2002; Daitch, 2011).

Finally, a third new explanation for generalized anxiety disorder, the avoidance theory, developed by researcher Thomas Borkovec, suggests that people with this disorder have greater bodily arousal (higher heart rate, perspiration, respiration) than other people and that worrying actually serves to reduce this arousal, perhaps by distracting the individuals from their unpleasant physical feelings (Newman et al., 2011; Borkovec, Alcaine, & Behar, 2004). In short, the avoidance theory holds that people with generalized anxiety disorder worry repeatedly in order to reduce or avoid uncomfortable states of bodily arousal. When, for example, they find themselves in an uncomfortable job situation or social relationship, they implicitly choose to intellectualize (that is, worry about) losing their job or losing their friend rather than having to stew in a state of intense negative arousal. The worrying serves as a quick, though ultimately maladaptive, way of coping with unpleasant bodily states.

Borkovec’s explanation has also been supported by numerous studies. Research reveals that people with generalized anxiety disorder experience particularly fast and intense bodily reactions, find such reactions overwhelming and unpleasant, worry more than other people upon becoming aroused, and successfully reduce their arousal whenever they worry (Hirsch et al., 2012; Aldao & Mennim, 2012; Fisher & Wells, 2011).

Cognitive TherapiesTwo kinds of cognitive approaches are used in cases of generalized anxiety disorder. In one, based on the pioneering work of Ellis and Beck, therapists help clients change the maladaptive assumptions that characterize their disorder. In the other, new-

CHANGING MALADAPTIVE ASSUMPTIONSIn Ellis’ technique of rational-emotive therapy, therapists point out the irrational assumptions held by clients, suggest more appropriate assumptions, and assign homework that gives the clients practice at challenging old assumptions and applying new ones (Ellis, 2014, 2008, 2005). Studies suggest that this approach and similar cognitive approaches bring at least modest relief to those suffering from generalized anxiety (Clark & Beck, 2012, 2010). Ellis’ approach is illustrated in the following discussion between him and an anxious client who fears failure and disapproval at work, especially over a testing procedure that she has developed for her company:

rational-emotive therapy A cognitive therapy developed by Albert Ellis that helps clients identify and change the irrational assumptions and thinking that help cause their psychological disorder

rational-emotive therapy A cognitive therapy developed by Albert Ellis that helps clients identify and change the irrational assumptions and thinking that help cause their psychological disorder

|

Client: |

I’m so distraught these days that I can hardly concentrate on anything for more than a minute or two at a time. My mind just keeps wandering to that damn testing procedure I devised, and that they’ve put so much money into; and whether it’s going to work well or be just a waste of all that time and money…. |

|

Ellis: |

Point one is that you must admit that you are telling yourself something to start your worrying going, and you must begin to look, and I mean really look, for the specific nonsense with which you keep reindoctrinating yourself…. The false statement is: “If, because my testing procedure doesn’t work and I am functioning inefficiently on my job, my co- |

|

Client: |

But if I want to do what my firm also wants me to do, and I am useless to them, aren’t I also useless to me? |

|

Ellis: |

No— |

|

|

(Ellis, 1962, pp. 160– |

BETWEEN THE LINES

Needless Worries

|

60 |

Percentage of things people worry about that will never occur |

|

30 |

Percentage of past, unchangeable events that people worry about |

|

88 |

Percentage of health- |

|

90 |

Percentage of things people worry about that are objectively considered insignificant |

|

Information from: NIMH, 2012 |

|

BREAKING DOWN WORRYINGAlternatively, some of today’s new-

Treating individuals with generalized anxiety disorder by helping them to recognize their inclination to worry is similar to another cognitive approach that has gained popularity in recent years. The approach, mindfulness-

Mindfulness-

The Biological Perspective

Biological theorists believe that generalized anxiety disorder is caused chiefly by biological factors. For years this claim was supported primarily by family pedigree studies, in which researchers determine how many and which relatives of a person with a disorder have the same disorder. If biological tendencies toward generalized anxiety disorder are inherited, people who are biologically related should have similar probabilities of developing this disorder. Studies have in fact found that biological relatives of persons with generalized anxiety disorder are more likely than nonrelatives to have the disorder also (Schienle et al., 2011; Domschke & Deckert, 2010). Approximately 15 percent of the relatives of people with the disorder display it themselves—

family pedigree study A research design in which investigators determine how many and which relatives of a person with a disorder have the same disorder.

family pedigree study A research design in which investigators determine how many and which relatives of a person with a disorder have the same disorder.

Of course, investigators cannot have full confidence in biological interpretations of such findings. Because relatives are likely to share aspects of the same environment, their shared disorders may reflect similarities in environment and upbringing rather than similarities in biological makeup. And, indeed, the closer the relatives, the more similar their environmental experiences are likely to be. Because identical twins are more physically alike than fraternal twins, they may even have more similarities in their upbringing.

Biological Explanations: GABA InactivityIn recent decades, important discoveries by brain researchers have offered clearer evidence that generalized anxiety disorder is related to biological factors (Bergado-

benzodiazepines The most common group of antianxiety drugs, which includes Valium and Xanax.

benzodiazepines The most common group of antianxiety drugs, which includes Valium and Xanax.

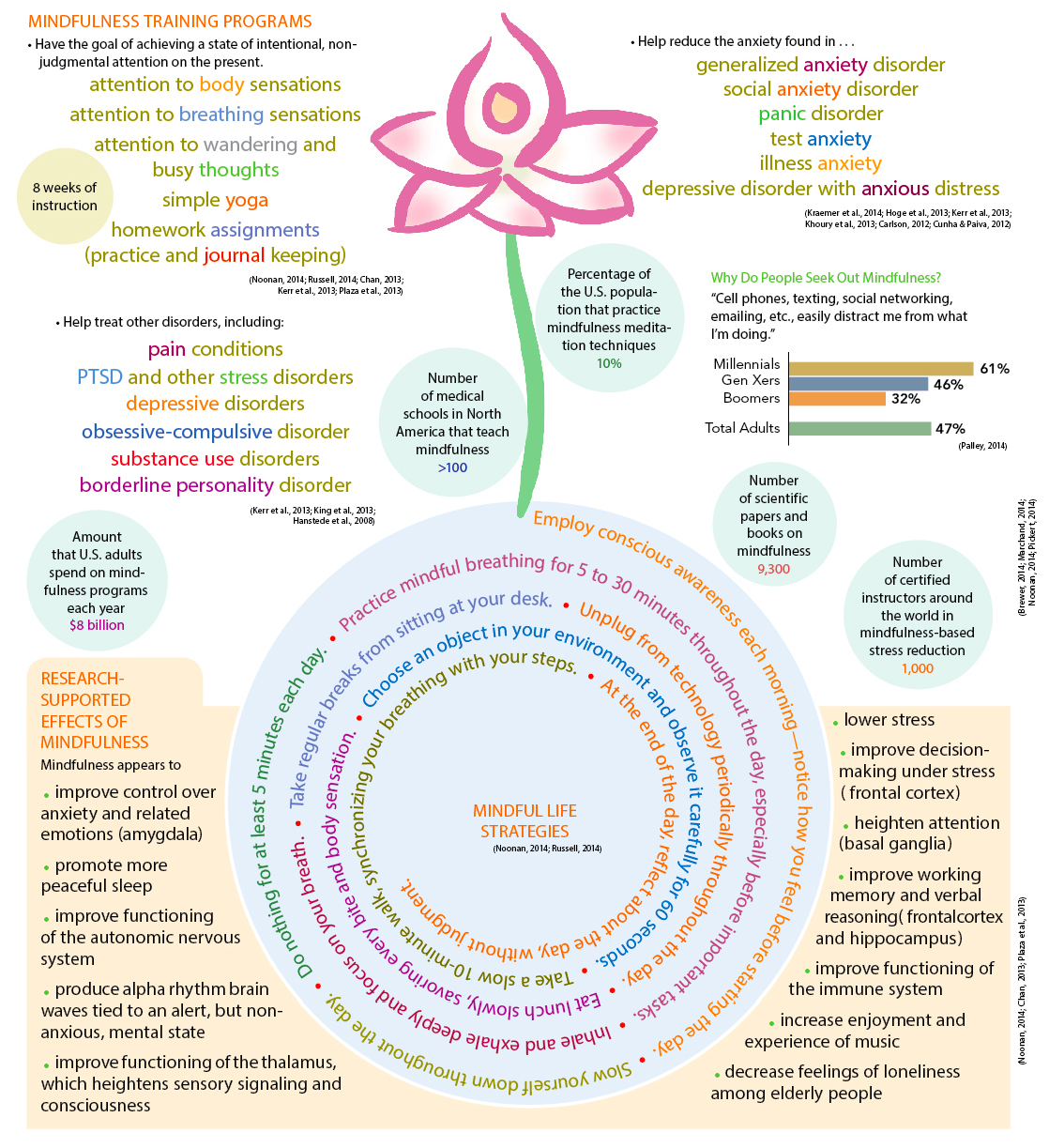

InfoCentral

MINDFULNESS

Over the past decade, mindfulness has become one of the most common terms in psychology. Mindfulness involves being in the present moment, intentionally and nonjudgmentally. Mindfulness training programs use mindfulness meditation techniques to help treat people suffering from pain, anxiety disorders, and depressive disorders, as well as a variety of other psychological disorders.

Investigators soon discovered that these benzodiazepine receptors ordinarily receive gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), a common neurotransmitter in the brain. As you read in Chapter 3, neurotransmitters are chemicals that carry messages from one neuron to another. GABA carries inhibitory messages: when GABA is received at a receptor, it causes the neuron to stop firing.

gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A neurotransmitter whose low activity has been linked to generalized anxiety disorder.

gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A neurotransmitter whose low activity has been linked to generalized anxiety disorder.

On the basis of such findings, biological researchers eventually pieced together several scenarios of how fear reactions may occur. A leading one began with the notion that in normal fear reactions, key neurons throughout the brain fire more rapidly, triggering the firing of still more neurons and creating a general state of excitability throughout the brain and body. Perspiration, breathing, and muscle tension increase. This state is experienced as fear or anxiety. Continuous firing of neurons eventually triggers a feedback system—

Some researchers have concluded that a malfunction in this feedback system can cause fear or anxiety to go unchecked (Bremner & Charney, 2010; Roy-

This explanation continues to have many supporters, but it is also problematic. First, according to recent biological discoveries, other neurotransmitters may also play important roles in anxiety and generalized anxiety disorder, either acting alone or in conjunction with GABA (Baldwin et al., 2013; Martin & Nemeroff, 2010; Burijon, 2007). Second, biological theorists are faced with the problem of establishing a causal relationship. The abnormal GABA responses of anxious persons may be the result, rather than the cause, of their anxiety disorders. Perhaps long-

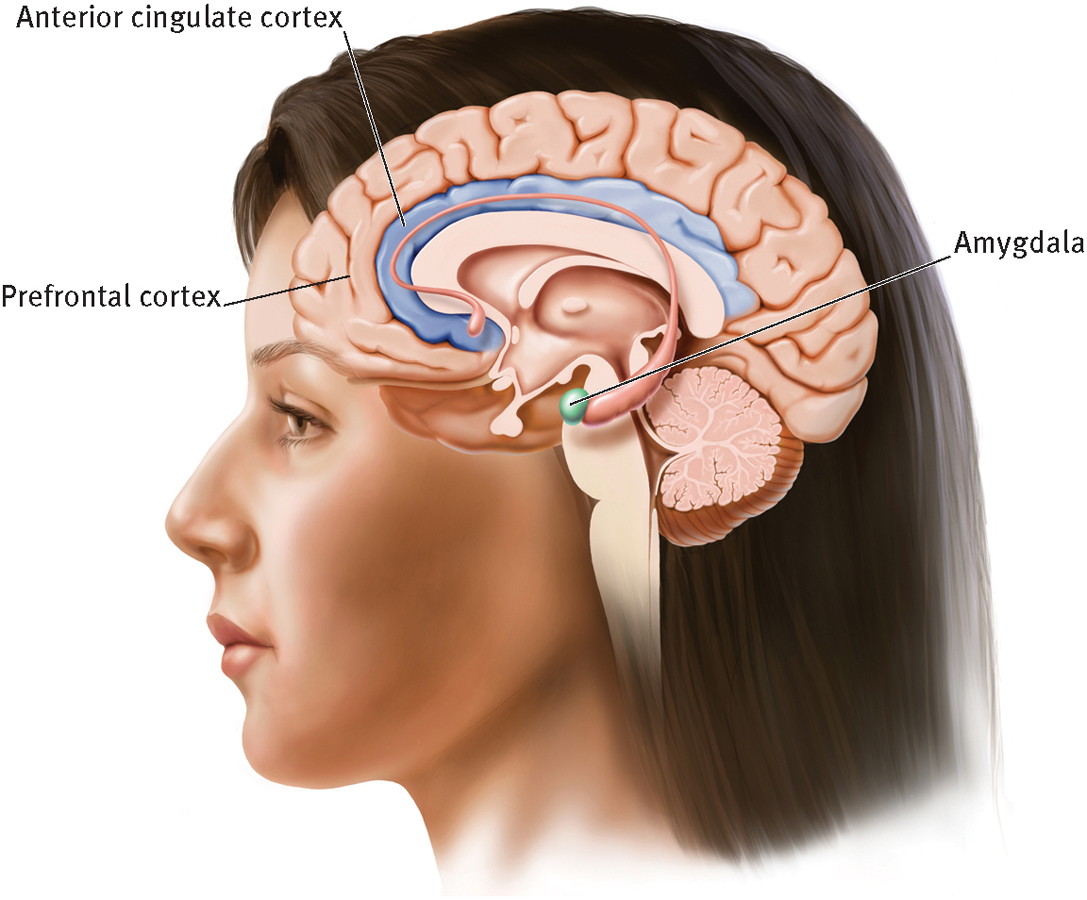

In fact, research conducted in recent years indicates that the root of generalized anxiety disorder is probably more complicated than the activity of a single neurotransmitter or group of neurotransmitters. Researchers have determined, for example, that emotional reactions of various kinds are tied to brain circuits—networks of brain structures that work together, triggering each other into action with the help of neurotransmitters and producing a particular kind of emotional reaction. It turns out that the circuit that produces anxiety reactions includes the prefrontal cortex; the anterior cingulate cortex; and the amygdala, a small almond-

The biology of anxiety

The circuit in the brain that helps produce anxiety reactions includes areas such as the amygdala, the prefrontal cortex, and the anterior cingulate cortex.

Biological TreatmentsThe leading biological treatment for generalized anxiety disorder is drug therapy (see Table 5-4). Other biological interventions are relaxation training and biofeedback.

|

Generic Name |

Trade Name(s) |

|---|---|

|

Alprazolam |

Xanax, Xanax XR |

|

Bromazepam |

Lectopam, Lexotan, Bromaze |

|

Chlordiazepoxide |

Librium |

|

Clonazepam |

Klonopin |

|

Clorazepate |

Tranxene |

|

Diazepam |

Valium |

|

Estazolam |

ProSom |

|

Flunitrazepam |

Rohypnol |

|

Flurazepam |

Dalmadorm, Dalmane |

|

Halazepam |

Paxipam |

|

Lorazepam |

Ativan |

|

Midazolam |

Versed |

|

Nitrazepam |

Mogadon, Alodorm, Pacisyn, Dumolid |

|

Oxazepam |

Serax |

|

Prazepam |

Lysanxia, Centrax |

|

Quazepam |

Doral |

|

Temazepam |

Restoril |

|

Triazolam |

Halcion |

ANTIANXIETY DRUG THERAPYIn the late 1950s, benzodiazepines were originally marketed as sedative-hypnotic drugs—drugs that calm people in low doses and help them fall asleep in higher doses. These new antianxiety drugs seemed less addictive than previous sedative-

sedative-hypnotic drugs Drugs that calm people at lower doses and help them to fall asleep at higher doses.

sedative-hypnotic drugs Drugs that calm people at lower doses and help them to fall asleep at higher doses.

Why are antianxiety drugs so popular in today’s world? Does their popularity say something about our society?

Only years later did investigators come to understand the reasons for the effectiveness of benzodiazepines. As you have read, researchers eventually learned that there are specific neuron sites in the brain that receive benzodiazepines and that these same receptor sites ordinarily receive the neurotransmitter GABA. Apparently, when benzodiazepines bind to these neuron receptor sites, particularly those receptors known as GABA-

Studies indicate that benzodiazepines often provide relief for people with generalized anxiety disorder (Islam et al., 2014; Hadley et al., 2012). However, clinicians have come to realize the potential dangers of these drugs. First, for many people, when the medications are stopped, anxiety returns as strong as ever. Second, we now know that people who take benzodiazepines in large doses for an extended time can become physically dependent on them. Third, the drugs can produce undesirable effects such as drowsiness, lack of coordination, memory loss, depression, and aggressive behavior. Finally, the drugs mix badly with certain other drugs or substances. If, for example, people on benzodiazepines drink even small amounts of alcohol, their breathing can slow down dangerously (Chollet et al., 2013).

In recent decades, still other kinds of drugs have become available for people with generalized anxiety disorder. In particular, it has been discovered that a number of antidepressant medications, drugs that are usually used to lift the moods of depressed persons, and antipsychotic medications, drugs commonly given to people who lose touch with reality, are also helpful to many people with generalized anxiety disorder. In fact, a number of today’s clinicians are more inclined to prescribe antidepressants or antipsychotics to treat generalized anxiety disorder than the GABA-

RELAXATION TRAININGA nonchemical biological technique commonly used to treat generalized anxiety disorder is relaxation training. The notion behind this approach is that physical relaxation will lead to a state of psychological relaxation. In one version, therapists teach clients to identify individual muscle groups, tense them, release the tension, and ultimately relax the whole body. With continued practice, they can bring on a state of deep muscle relaxation at will, reducing their state of anxiety.

relaxation training A treatment procedure that teaches clients to relax at will so they can calm themselves in stressful situations.

relaxation training A treatment procedure that teaches clients to relax at will so they can calm themselves in stressful situations.

Research indicates that relaxation training is more effective than no treatment or placebo treatment in cases of generalized anxiety disorder (Hayes-

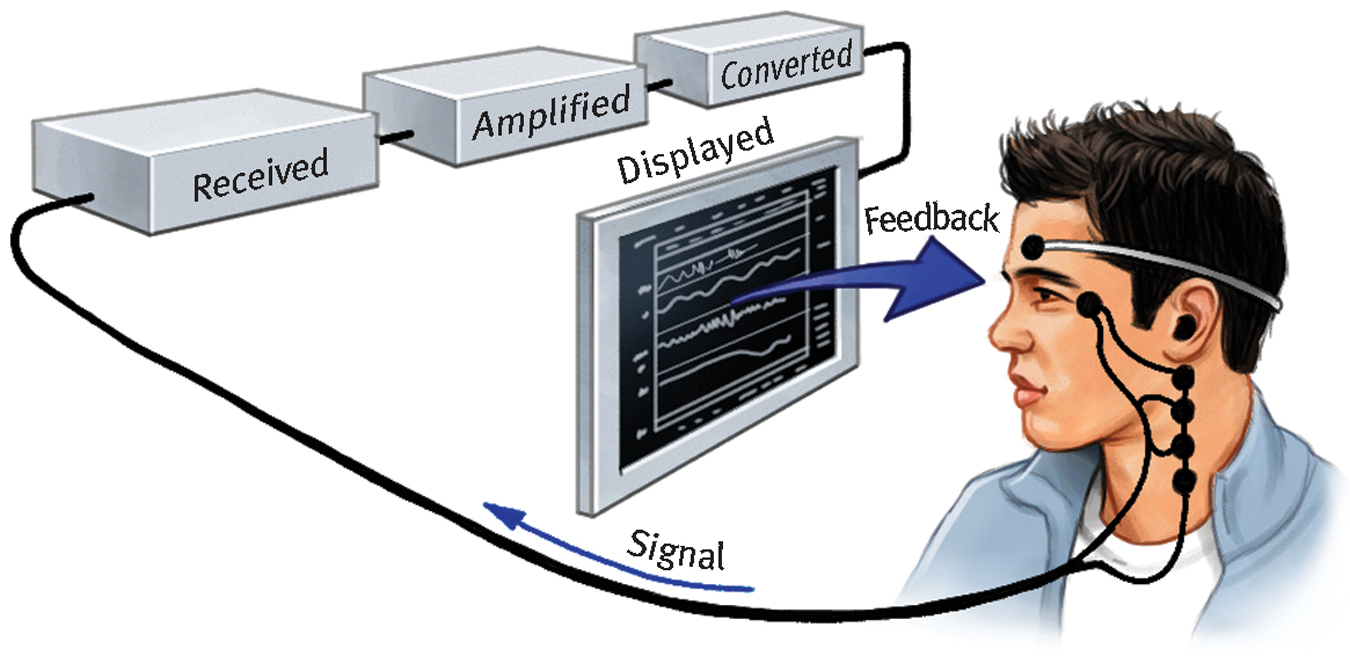

BIOFEEDBACKIn biofeedback, therapists use electrical signals from the body to train people to control physiological processes such as heart rate or muscle tension. Clients are connected to a monitor that gives them continuous information about their bodily activities. By attending to the signals from the monitor, they may gradually learn to control even seemingly involuntary physiological processes.

biofeedback A technique in which a client is given information about physiological reactions as they occur and learns to control the reactions voluntarily.

biofeedback A technique in which a client is given information about physiological reactions as they occur and learns to control the reactions voluntarily.

The most widely applied method of biofeedback for the treatment of anxiety uses a device called an electromyograph (EMG), which provides feedback about the level of muscular tension in the body. Electrodes are attached to the client’s muscles—

electromyograph (EMG) A device that provides feedback about the level of muscular tension in the body.

electromyograph (EMG) A device that provides feedback about the level of muscular tension in the body.

Biofeedback at work

This biofeedback system records tension in the forehead muscles of an anxious person. The system receives, amplifies, converts, and displays information about the tension, allowing the client to “observe” it and to try to reduce his tension responses.

Research finds that, in most cases, EMG biofeedback, like relaxation training, has only a modest effect on a person’s anxiety level (Brambrink, 2004). As you will see in Chapter 10, biofeedback has had its greatest impact when it plays an adjunct role in the treatment of certain medical problems, including headaches and back pain (Flor, 2014; Young & Kemper, 2013; Astin, 2004).