9.4 What Causes Eating Disorders?

multidimensional risk perspective A theory that identifies several kinds of risk factors that are thought to combine to help cause a disorder. The more factors present, the greater the risk of developing the disorder.

Most of today’s theorists and researchers use a multidimensional risk perspective to explain eating disorders. That is, they identify several key factors that place a person at risk for these disorders (Jacobi & Fittig, 2010). The more of these factors that are present, the more likely it is that a person will develop an eating disorder. As you will see, most of the factors that have been cited and investigated center on anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Binge-

Psychodynamic Factors: Ego Deficiencies

Hilde Bruch, a pioneer in the study and treatment of eating disorders, was mentioned earlier in this chapter. Bruch developed a largely psychodynamic theory of the disorders. She argued that disturbed mother–

According to Bruch, parents may respond to their children either effectively or ineffectively. Effective parents accurately attend to their children’s biological and emotional needs, giving them food when they are crying from hunger and comfort when they are crying out of fear. Ineffective parents, by contrast, fail to attend to their children’s needs, deciding that their children are hungry, cold, or tired without correctly interpreting the children’s actual condition. They may feed their children when their children are anxious rather than hungry or comfort them when they are tired rather than anxious. Children who receive such parenting may grow up confused and unaware of their own internal needs, not knowing for themselves when they are hungry or full and unable to identify their own emotions.

Because they cannot rely on internal signals, these children turn instead to external guides, such as their parents. They seem to be “model children,” but they fail to develop genuine self-

There is a peculiar contradiction—

(Bruch, 1978, p. 128)

Clinical reports and research have provided some support for Bruch’s theory (Holtom-

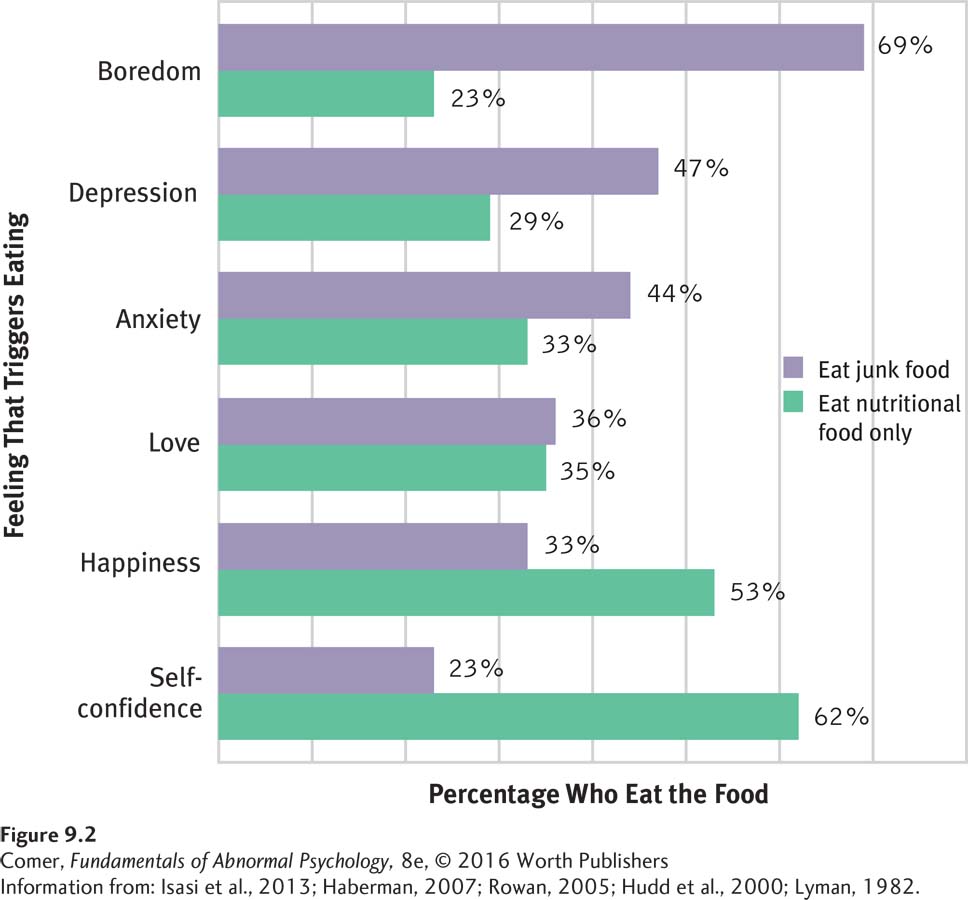

Research has also supported Bruch’s belief that people with eating disorders perceive internal cues, including emotional cues, inaccurately (Lavender et al., 2014; Fairburn et al., 2008). When research participants with an eating disorder are anxious or upset, for example, many of them mistakenly think they are also hungry (see Figure 9.2), and they respond as they might respond to hunger—

Cognitive Factors

If you look closely at Bruch’s explanation of eating disorders, you’ll see that it contains several cognitive ideas. She held, for example, that as a result of ineffective parenting, people with eating disorders improperly label their internal sensations and needs, generally feel little control over their lives, and, in turn, want to have excessive levels of control over their body size, shape, and eating habits. According to cognitive theorists, these deficiencies contribute to a broad cognitive distortion that lies at the center of disordered eating, namely, people with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa judge themselves—

How might you explain the finding that eating disorders tend to be less common in cultures that restrict a woman’s freedom to make decisions about her life?

As you saw earlier in the chapter, research indicates that people with eating disorders do indeed display such cognitive deficiencies (Siep et al., 2011). Although studies have not clarified that such deficiencies are the cause of eating disorders, many cognitive-

Depression

Many people with eating disorders, particularly those with bulimia nervosa, have symptoms of depression (Harrington et al., 2015). This finding has led some theorists to suggest that depressive disorders set the stage for eating disorders.

Their claim is supported by four kinds of evidence. First, many more people with an eating disorder qualify for a clinical diagnosis of major depressive disorder than do people in the general population. Second, the close relatives of people with eating disorders seem to have a higher rate of depressive disorders than do close relatives of people without such disorders. Third, as you will soon see, many people with eating disorders, particularly bulimia nervosa, have low activity of the neurotransmitter serotonin, similar to the serotonin abnormalities found in people with depression. And finally, people with eating disorders are often helped by some of the same antidepressant drugs that reduce depression. Of course, although such findings suggest that depression may help cause eating disorders, other explanations are possible. For example, the pressure and pain of having an eating disorder may cause depression.

Biological Factors

Biological theorists suspect that certain genes may leave some people particularly susceptible to eating disorders (Starr & Kreipe, 2014). Consistent with this idea, relatives of people with eating disorders are up to six times more likely than other people to develop the disorders themselves (Thornton et al., 2011; Strober et al., 2001, 2000). Moreover, if one identical twin has anorexia nervosa, the other twin also develops the disorder in as many as 70 percent of cases; in contrast, the rate for fraternal twins, who are genetically less similar, is 20 percent. Similarly, in the case of bulimia nervosa, identical twins display a concordance rate of 23 percent, compared with a rate of 9 percent among fraternal twins (Thornton et al., 2011; Kendler et al., 1995, 1991).

One factor that has interested investigators is the possible role of serotonin. Several research teams have found a link between eating disorders and the genes responsible for the production of this neurotransmitter, and still others have measured low serotonin activity in many people with eating disorders (Phillips et al., 2014; Starr & Kreipe, 2014). Thus some theorists suspect that abnormal serotonin activity causes the bodies of some people to crave and binge on high-

hypothalamus A part of the brain that helps regulate various bodily functions, including eating and hunger.

lateral hypothalamus (LH) A brain region that produces hunger when activated.

ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) A brain region that depresses hunger when activated.

Other biological researchers explain eating disorders by pointing to the hypothalamus, a part of the brain that regulates many bodily functions (Berthoud, 2012). Researchers have located two separate areas in the hypothalamus that help control eating. One, the lateral hypothalamus (LH), produces hunger when it is activated. When the LH of a laboratory animal is stimulated electrically, the animal eats, even if it has been fed recently. In contrast, another area, the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH), reduces hunger when it is activated. When the VMH is electrically stimulated, laboratory animals stop eating.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Smoking, Eating, and Weight

75 percent of people who quit smoking gain weight.

Nicotine, a stimulant substance, suppresses appetites and increases metabolic rate, perhaps because of its impact on the lateral hypothalamus.

(Kroemer et al., 2013; Higgins & George, 2007)

These areas of the hypothalamus and related brain structures are apparently activated by chemicals from the brain and body, depending on whether the person is eating or fasting (Schwartz, 2014; Petrovich, 2011). Two such brain chemicals are the natural appetite suppressants cholecystokinin (CCK) and glucagon-

weight set point The weight level that a person is predisposed to maintain, controlled in part by the hypothalamus.

Some researchers believe that the hypothalamus, related brain areas, and chemicals such as CCK and GLP-

According to the weight set point theory, when people diet and fall to a weight below their weight set point, their brain starts trying to restore the lost weight. Hypothalamic and related brain activity produce a preoccupation with food and a desire to binge. They also trigger bodily changes that make it harder to lose weight and easier to gain weight, however little is eaten (Yu et al., 2015; Higgins & George, 2007). Once the brain and body begin conspiring to raise weight in this way, dieters actually enter into a battle against themselves. Some people apparently manage to shut down the inner “thermostat” and control their eating almost completely. These people move toward restricting-

Societal Pressures

Eating disorders are more common in Western countries than in other parts of the world. Thus, many theorists believe that Western standards of female attractiveness are partly responsible for the emergence of the disorders (MacNeill & Best, 2015). Western standards of female beauty have changed throughout history, with a noticeable shift in preference toward a thin female frame in recent decades (Gilbert et al., 2005). One study that tracked the height, weight, and age of contestants in the Miss America Pageant from 1959 through 1978 found an average decline of 0.28 pound per year among the contestants and 0.37 pound per year among winners (Garner et al., 1980). The researchers also examined data on all Playboy magazine centerfold models over the same time period and found that the average weight, bust, and hip measurements of these women had decreased steadily. More recent studies of Miss America contestants and Playboy centerfolds indicate that these trends have continued (Rubinstein & Caballero, 2000).

Why do you think that fashion models, often called supermodels, have risen to celebrity status in recent decades?

Because thinness is especially valued in the subcultures of performers, fashion models, and certain athletes, members of these groups are likely to be particularly concerned and/or criticized about their weight. For example, after undergoing an inpatient treatment program for eating disorders, the popular singer and rapper Kesha recently wrote, “The music industry has set unrealistic expectations for what a body is supposed to look like, and I started becoming overly critical of my own body because of that” (Sebert, 2014).

Studies have found that performers, models, and athletes are indeed more prone than others to anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa (Arcelus, Witcomb, & Mitchell, 2014; Martinsen & Sundgot-

Attitudes toward thinness may also help explain economic differences in the rates of eating disorders. In the past, women in the upper socioeconomic classes expressed more concern about thinness and dieting than women of the lower socioeconomic classes (Margo, 1985). Correspondingly, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa were more common among women higher on the socioeconomic scale (Foreyt et al., 1996; Rosen et al., 1991). In recent years, however, dieting and preoccupation with thinness have increased to some degree in all socioeconomic classes, as has the prevalence of these eating disorders (Starr & Kreipe, 2014; Ernsberger, 2009).

Western society not only glorifies thinness but also creates a climate of prejudice against overweight people (Puhl et al., 2015). Whereas slurs based on ethnicity, race, and gender are considered unacceptable, cruel jokes about obesity are standard fare on the Web and television and in movies, books, and magazines. Research indicates that the prejudice against obese people is deep-

Given these trends, it is not totally surprising that a recent survey of 248 adolescent girls directly tied eating disorders and body dissatisfaction to social networking, Internet activity, and television browsing (Latzer, Katz, & Spivak, 2011) (see MindTech below). The survey found that the respondents who spent more time on Facebook were more likely to display eating disorders, have negative body image, eat in dysfunctional ways, and want to diet. Those who spent more time on fashion and music Web sites and those who viewed more gossip-

Family Environment

Families may play an important role in the development and maintenance of eating disorders (Hoste, Lebow, & Le Grange, 2014). Research suggests that as many as half of the families of people with anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa have a long history of emphasizing thinness, physical appearance, and dieting. In fact, the mothers in these families are more likely to diet themselves and to be generally perfectionistic than are the mothers in other families (Zerbe, 2008; Woodside et al., 2002).

enmeshed family pattern A family system in which members are overinvolved with each other’s affairs and overconcerned about each other’s welfare.

Abnormal interactions and forms of communication within a family may also set the stage for an eating disorder (Holtom-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Teasing and Eating

When it comes to eating disorders, teasing is no laughing matter (Hilbert et al., 2013; Neumark-

In an enmeshed system, family members are overinvolved in each other’s affairs and overconcerned with the details of each other’s lives. On the positive side, enmeshed families can be affectionate and loyal. On the negative side, they can be clingy and foster dependency. Parents are too involved in the lives of their children, allowing little room for individuality and independence. Minuchin argues that adolescence poses a special problem for these families. The teenager’s normal push for independence threatens the family’s apparent harmony and closeness. In response, the family may subtly force the child to take on a “sick” role—

MindTech

Dark Sites of the Internet

Dark Sites of the Internet

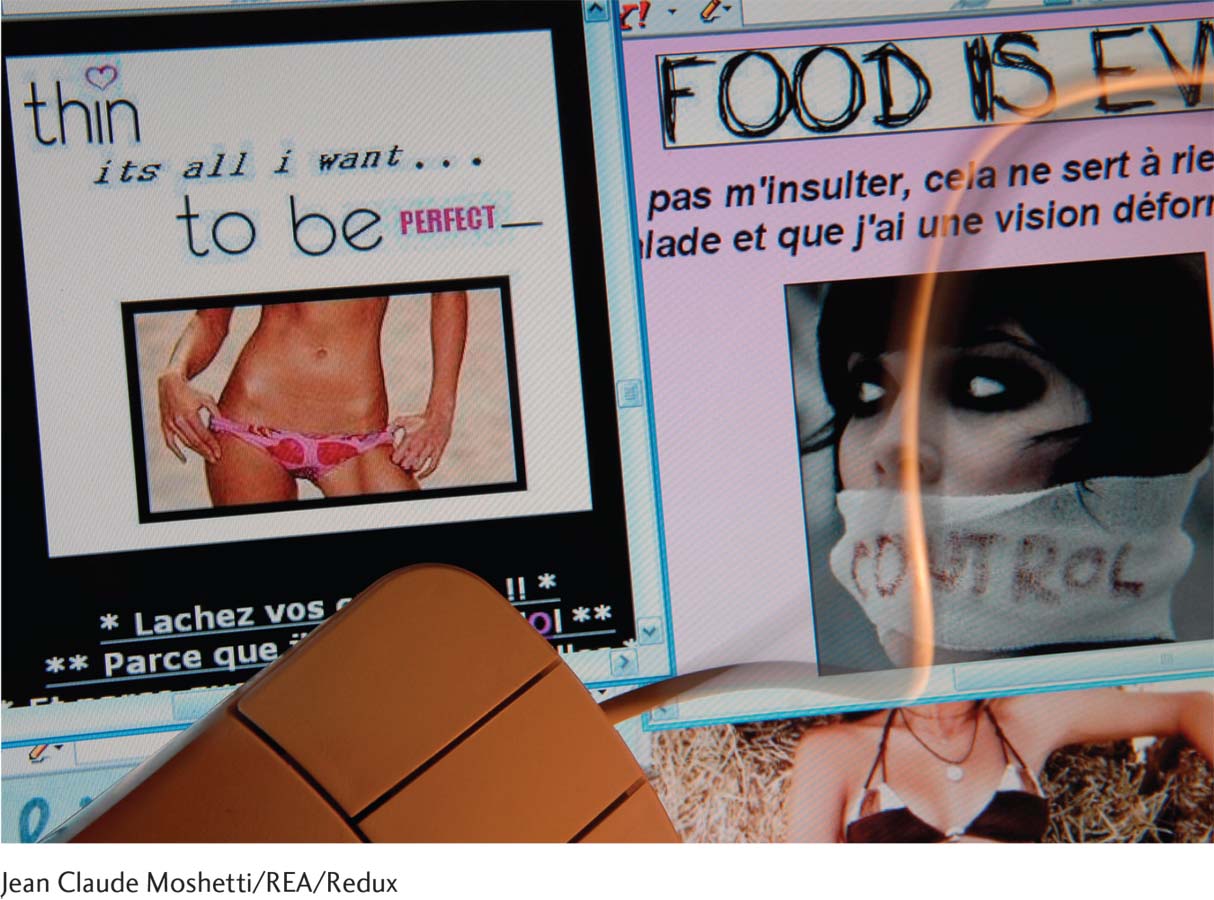

Clinicians, researchers, and other mental health practitioners try to combat psychological disorders—

Besides promoting eating disorders, might there be other ways in which pro-

The Eating Disorders Association reports that there are more than 500 pro-

Many users of the sites exchange tips on how they can starve themselves and disguise their weight loss from family, friends, and doctors (Christodoulou, 2012). The sites may also offer support and feedback about starvation diets. Many of the sites offer mottos, emotional messages, and photos and videos of extremely thin actresses and models as “thinspiration” (Mathis, 2014).

The pro-

Many people worry that pro-

Multicultural Factors: Racial and Ethnic Differences

In the popular 1995 movie Clueless, Cher and Dionne, wealthy teenage friends of different races, have similar tastes, beliefs, and values about everything from boys to schoolwork. In particular, they have the same kinds of eating habits and beauty ideals, and they are even similar in weight and physical form. But does the story of these young women reflect the realities of white American and African American females in our society?

In the early 1990s, the answer to this question appeared to be a resounding no. Most studies conducted up to the time of the movie’s release indicated that the eating behaviors, values, and goals of young African American women were considerably healthier than those of young white American women (Lovejoy, 2001; Cash & Henry, 1995; Parker et al., 1995). A widely publicized 1995 study at the University of Arizona, for example, found that the eating behaviors and attitudes of young African American women were more positive than those of young white American women. It found, specifically, that nearly 90 percent of the white American respondents were dissatisfied with their weight and body shape, compared with around 70 percent of the African American teens.

The study also suggested that white American and African American adolescent girls had different ideals of beauty. The white American teens, asked to define the “perfect girl,” described a girl of 5’ 7” weighing between 100 and 110 pounds—

Unfortunately, research conducted over the past decade suggests that body image concerns, dysfunctional eating patterns, and anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are on the rise among young African American women as well as among women of other minority groups (Starr & Kreipe, 2014; Gilbert, 2011). For example, a survey conducted by Essence—the largest-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Climate Control

Women who live in warmer climates (where more revealing clothing is worn) have lower weight, engage in more binge eating and purging, and have more body image concerns than women who live in cooler climates (Sloan, 2002).

The shift in the eating behaviors and eating problems of African American women appears to be partly related to their acculturation (Kroon Van Diest et al., 2014). One study compared African American women at a predominately white American university with those at a predominately African American university. Those at the former school had significantly higher depression scores, and those scores were positively correlated with eating problems (Ford, 2000).

Still other studies indicate that Hispanic American female adolescents and young adults engage in disordered eating behaviors and express body dissatisfaction at rates about equal to those of white American women (Blow & Cooper, 2014; Levine & Smolak, 2010). Moreover, those who consider themselves more oriented to white American culture have particularly high rates of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa (Cachelin et al., 2006). These eating disorders also appear to be on the increase among young Asian American women and young women in several Asian countries (Pike et al., 2013; Stewart & Williamson, 2008). In one Taiwanese study, for example, 65 percent of the underweight girls aged 10 to 14 years said they wished they were thinner (Wong & Huang, 2000).

Multicultural Factors: Gender Differences

Males account for only 5 to 10 percent of all people with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. The reasons for this striking gender difference are not entirely clear, but Western society’s double standard for attractiveness is, at the very least, one reason. Our society’s emphasis on a thin appearance is clearly aimed at women much more than men, and some theorists believe that this difference has made women much more inclined to diet and more prone to eating disorders. Surveys of college men have, for example, found that the majority select “muscular, strong and broad shoulders” to describe the ideal male body and “thin, slim, slightly underweight” to describe the ideal female body (Mayo & George, 2014; Toro et al., 2005).

A second reason for the different rates of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa between men and women may be the different methods of weight loss favored by the two genders. According to some clinical observations, men are more likely to use exercise to lose weight, whereas women more often diet (Gadalla, 2009; Toro et al., 2005). And, as you have read, dieting often precedes the onset of these eating disorders.

Why do you think that the prevalence of eating disorders among men has been on the increase in recent years?

Why do some men develop anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa? In a number of cases, the disorder is linked to the requirements and pressures of a job or sport (Morgan, 2012; Thompson & Sherman, 2011). According to one study, 37 percent of men with these eating disorders had jobs or played sports for which weight control was important, compared with 13 percent of women with such disorders (Braun, 1996). The highest rates of male eating disorders have been found among jockeys, wrestlers, distance runners, body builders, and swimmers. Jockeys commonly spend hours before a race in a sauna, shedding up to seven pounds of weight, and may restrict their food intake, abuse laxatives and diuretics, and force vomiting (Kerr et al., 2007).

BETWEEN THE LINES

Saintly Restraint

During the Middle Ages, restrained eating, prolonged fasting, or purging by a number of female saints was greatly admired and was even counted among their miracles. Catherine of Siena sometimes pushed twigs down her throat to bring up food, Mary of Oignies and Beatrice of Nazareth vomited from the mere smell of meat, and Columba of Rieti died of self-

For other men who develop anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, body image appears to be a key factor, just as it is in women (Mayo & George, 2014; Mond et al., 2014). Many report that they want a “lean, toned, thin” shape similar to the ideal female body, rather than the muscular, broad-

Still other men seem to be caught up in a different kind of eating disorder, called reverse anorexia nervosa or muscle dysmorphobia. Men with this disorder are very muscular but still see themselves as scrawny and small and therefore continue to strive for a “perfect” body through extreme measures such as excessive weight lifting or the abuse of steroids (Lin & DeCusati, 2015; Morgan, 2012). People with muscle dysmorphobia typically feel shame about their bodies, and many have a history of depression, anxiety, and self-

Summing Up

WHAT CAUSES EATING DISORDERS? Most theorists now use a multidimensional risk perspective to explain anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa and to identify several key contributing factors. These factors include ego deficiencies; cognitive factors; depression; biological factors such as activity of the hypothalamus, biochemical activity, and the body’s weight set point; society’s emphasis on thinness and bias against obesity; family environment; racial and ethnic differences; and gender differences. Which of these factors are also involved in binge-