Behavioral Therapies

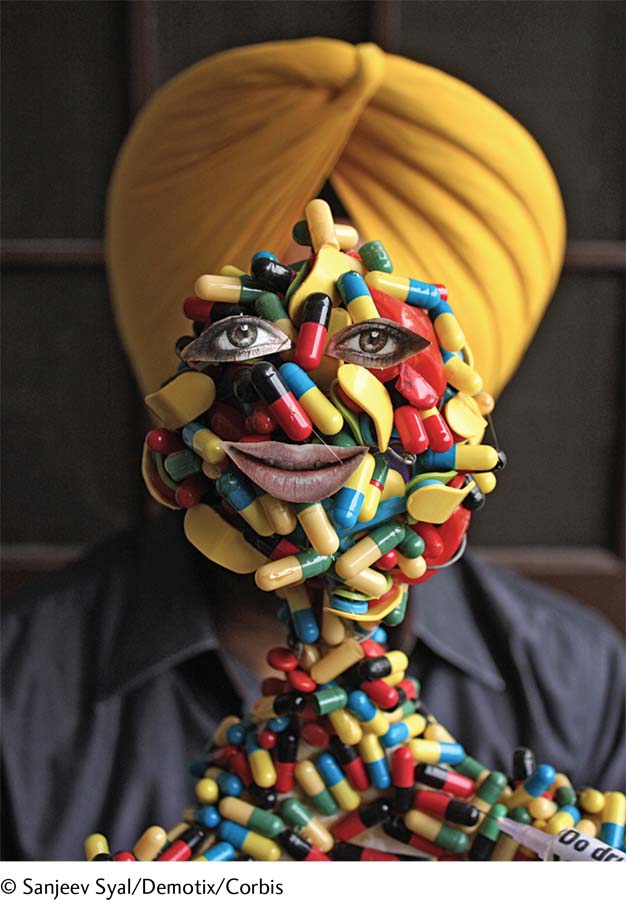

Spreading the word In a particularly innovative effort to increase public awareness about the dangers of drug abuse, Harwinder Singh Gill, an artist in India, created a model of the human body made up of capsule shells. Gill did this on the eve of the 2012 International Day Against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking.

aversion therapy A treatment in which clients are repeatedly presented with unpleasant stimuli while they are performing undesirable behaviors such as taking a drug.

A widely used behavioral treatment for substance use disorders is aversion therapy, an approach based on the principles of classical conditioning. Clients are repeatedly presented with an unpleasant stimulus (for example, an electric shock) at the very moment that they are taking a drug. After repeated pairings, they are expected to react negatively to the substance itself and to lose their craving for it.

Aversion therapy has been used to treat alcoholism more than it has to treat other substance use disorders. In one version of this therapy, drinking is paired with drug-induced nausea and vomiting (McCrady et al., 2014; Welsh & Liberto, 2001). The pairing of nausea with alcohol is expected to produce negative responses to alcohol itself. Another version of aversion therapy requires people with alcoholism to imagine extremely upsetting, repulsive, or frightening scenes while they are drinking. The pairing of the imagined scenes with alcohol is expected to produce negative responses to alcohol itself. Here is the kind of scene therapists may guide a client to imagine:

I’d like you to vividly imagine that you are tasting the (beer, whiskey, etc.). See yourself tasting it, capture the exact taste, color and consistency. Use all of your senses. After you’ve tasted the drink you notice that there is something small and white floating in the glass—it stands out. You bend closer to examine it more carefully, your nose is right over the glass now and the smell fills your nostrils as you remember exactly what the drink tastes like. Now you can see what’s in the glass. There are several maggots floating on the surface. As you watch, revolted, one manages to get a grip on the glass and, undulating, creeps up the glass. There are even more of the repulsive creatures in the glass than you first thought. You realise that you have swallowed some of them and you’re very aware of the taste in your mouth. You feel very sick and wish you’d never reached for the glass and had the drink at all.

(Clarke & Saunders, 1988, pp. 143–144)

A behavioral approach that has been effective in the short-term treatment of people who are addicted to cocaine and several other drugs is contingency management, which makes incentives (such as cash, vouchers, prizes, or privileges) contingent on the submission of drug-free urine specimens (Godley et al., 2014). In one pioneering study, 68 percent of cocaine abusers who completed a six-month contingency training program achieved at least eight weeks of continuous abstinence (Higgins et al., 2011, 1993).

Behavioral interventions for substance use disorders have usually had only limited success when they are the sole form of treatment (Belendiuk & Riggs, 2014; Carroll, 2008). A major problem is that the approaches can be effective only when people are motivated to continue using them despite their unpleasantness or demands. Generally, behavioral treatments work best in combination with either biological or cognitive approaches (Belendiuk & Riggs, 2014; Carroll & Kiluk, 2012).

Page 336

MediaSpeak

Jeff has been sober 22 months, he tells me. Without blinking or ducking, his clear blue eyes looking straight at me, he says that if it were not for Sobriety High, he’d be dead. I believe him…. Sobriety High started in Minneapolis in 1989 with just two students. It has 100 more today, and 33 sober high schools have sprung up in eight other states…. According to a National Institute on Drug Abuse study, 78% of the students in sober high schools attend after receiving formal rehab….

While [Sobriety High] undoubtedly feels like a school, the wall banners feature phrases like “Turning It Over Is A Turning Point” rather than, say, a sign for the prom. The students are diverse, with hair of all different lengths and colors; some have the seemingly requisite addict tattoos while others are decked out in Goth garb and still others project a distinctly Midwestern Wonder Bread aura. Their journeys are also diverse, with the lucky ones landing here after treatment but many coming from the courts, detox or the streets….

….he classes are small so that teachers can check in with each student regularly and the curriculum flexible so as to help them with what they missed while they were using or in treatment. Some programs help students—many with hair-raising records—find work. Some also work with chemically dependent parents and older siblings as well. Students typically have “group” each day, and while it is not an AA meeting, the DNA of AA is evident….

What advantages might sober schools have over other substance abuse interventions?

All teenagers have low impulse control but the stakes are higher for chemically dependent kids trying to stay sober. Says Joe Schrank, …. board member of the National Youth Recovery Foundation, ….#8220;When you put pot and booze on top of adolescent stupidity, kids are at risk.” …

Just try adding acne, constant temptation and regularly being heckled that you’re a “pussy” to a standard newcomer’s recovery and you’ll see just how high the deck is stacked against teenage sobriety; the notion of placing them in an environment that caters to clean living thus makes sense….

Ninety percent of students at Sobriety High have other mental health issues besides chemical dependency [and] need the extra support of counselors, psychologists, and ongoing mental health support, and this is costly…. “It takes more money per student, and the schools must be on a segregated site if they are to have a drug and alcohol free campus.” …

For barely sober teens ….losing recovery schools would be disastrous. “Many of them will go back to the streets, or prison, or they will be dead,” says ….he Sobriety High social worker…. Supporters ….oint out that closing recovery schools makes little fiscal sense. “Recovery school is a fraction of the cost of incarceration,” says Joe Schrank…. “Look at Drug Courts,” adds former Congressman Jim Ramstad. “The recidivism rate for those who complete the course is 24% while the rate for criminal court is 75%.” …

[Social worker Debbie Bolton] says plainly, “What we do is important. We save lives.”

“Most Sober High Schools Are Very Successful. So Why Are They Facing the Ax?” By Jeff Forester, TheFix.com (addiction website), 6/18/2011.

Page 337

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies

Better ways to cope Several treatments for substance use disorders, including relapse-prevention training, teach clients alternative—more functional—ways of coping with stress and negative emotions. In that spirit, this patient at a drug rehabilitation center in China developed the practice of kicking a punching dummy to help release his pent-up anger.

Cognitive-behavioral treatments for substance use disorders help clients identify and change the behaviors and cognitions that keep contributing to their patterns of substance misuse (Gregg et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2012). Practitioners of these approaches also help the clients develop more effective coping skills—skills that can be applied during times of stress, temptation, and substance craving.

relapse-prevention training A cognitive-behavioral approach to treating alcohol use disorder in which clients are taught to keep track of their drinking behavior, apply coping strategies in situations that typically trigger excessive drinking, and plan ahead for risky situations and reactions.

Perhaps the most prominent cognitive-behavioral approach to substance misuse is relapse-prevention training (Jhanjee, 2014; Daley et al., 2011). The overall goal of this approach is for clients to gain control over their substance-related behaviors. To help reach this goal, clients are taught to identify high-risk situations, appreciate the range of decisions that confront them in such situations, change their dysfunctional lifestyles, and learn from mistakes and lapses.

Several strategies typically are included in relapse-prevention training for alcohol use disorder: (1) Therapists have clients keep track of their drinking by writing down the times, locations, emotions, bodily changes, and other circumstances of their drinking. (2) Therapists teach clients coping strategies to use when such situations arise, strategies such as employing relaxation techniques, spacing their drinks, or sipping drinks rather than gulping. (3) Therapists teach clients to plan ahead of time, determining beforehand how many drinks are appropriate, what to drink, and under which circumstances to drink.

Relapse-prevention training has been found to lower some people’s frequency of intoxication and of binge drinking (Jhanjee, 2014; Borden et al., 2011). People who are young and do not have the tolerance and withdrawal features of chronic alcohol use seem to do best with this approach (Hart & Ksir, 2014; Deas et al., 2008).

Another form of cognitive-behavioral treatment that has been used in cases of substance use disorder is acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), the mindfulness-based approach that helps clients become aware of their streams of thoughts as they are occurring and to accept such thoughts as mere events of the mind (see Chapters 2 and 4). For people with substance use disorders, that means increasing their awareness and acceptance of their drug cravings, worries, and depressive thoughts. By accepting such thoughts rather than trying to eliminate them, the clients are expected to be less upset by them and less likely to act on them by seeking out drugs. Research indicates that ACT often is as effective as other cognitive-behavioral treatments for substance use disorders, and sometimes more effective (Lee et al., 2015; Bowen et al., 2014; Chiesa & Serretti, 2014).

Biological Treatments

Biological treatments may be used to help people withdraw from substances, abstain from them, or simply maintain their level of use without increasing it further. As with the other forms of treatment, biological approaches alone rarely bring long-term improvement, but they can be helpful when combined with other approaches.

detoxification Systematic and medically supervised withdrawal from a drug.

Detoxification Detoxification is systematic and medically supervised withdrawal from a drug. Some detoxification programs are offered on an outpatient basis. Others are located in hospitals and clinics and may also include individual and group therapy, a “full-service” institutional approach that has become popular. One detoxification approach is to have clients withdraw gradually from the substance, taking smaller and smaller doses until they are off the drug completely. A second—often medically preferred—detoxification strategy is to give clients other drugs that reduce the symptoms of withdrawal (Bisaga et al., 2015; Day & Strang, 2011). Antianxiety drugs, for example, are sometimes used to reduce severe alcohol withdrawal reactions such as delirium tremens and seizures. Detoxification programs seem to help motivated people withdraw from drugs (Müller et al., 2010). However, relapse rates tend to be high for those who do not receive a follow-up form of treatment—psychological, biological, or sociocultural—after successfully detoxifying (Blodgett et al., 2014).

Page 338

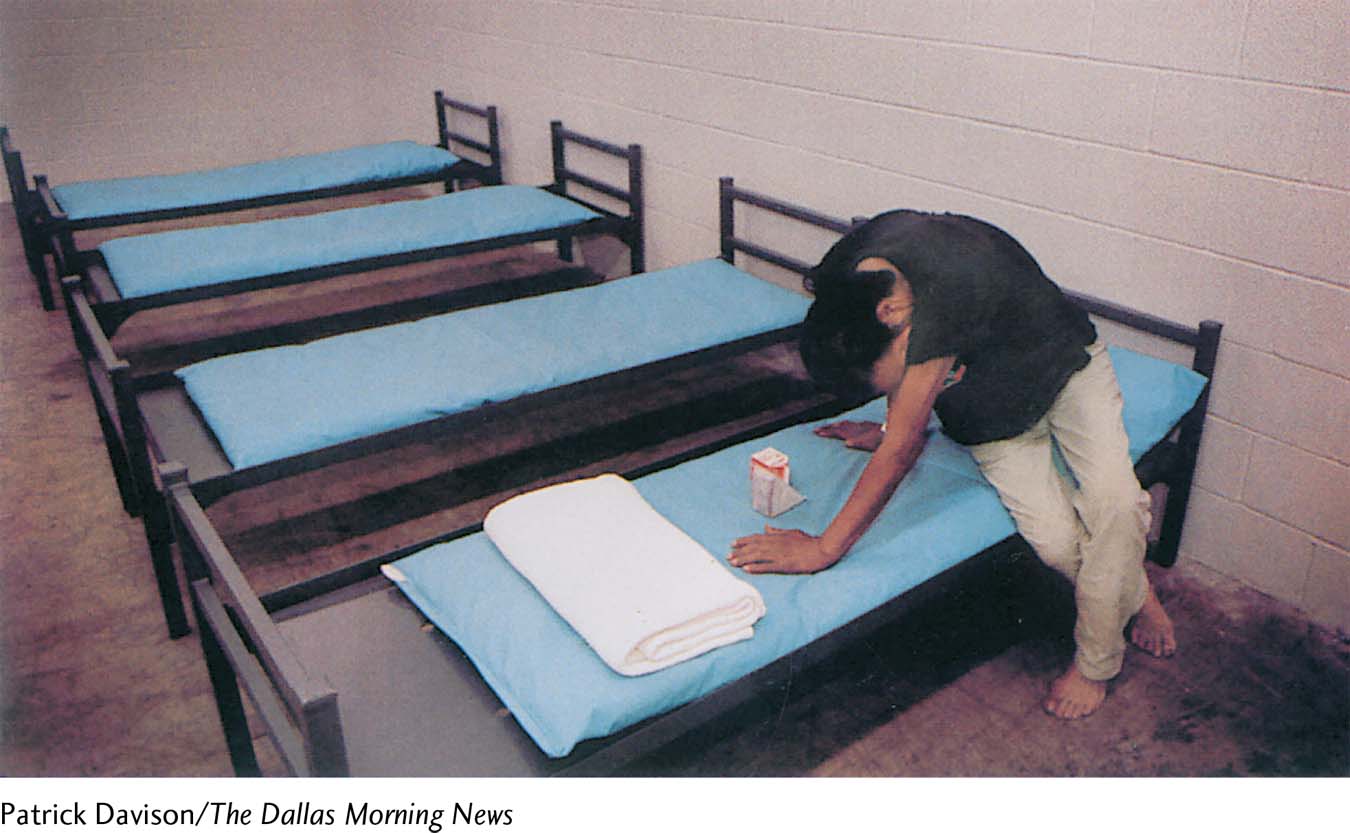

Forced detoxification Abstinence is not always medically supervised, nor is it necessarily planned or voluntary. This person, who is suffering from alcoholism, begins to have symptoms of withdrawal soon after being imprisoned for public intoxication.

antagonist drugs Drugs that block or change the effects of an addictive drug.

Antagonist Drugs After successfully stopping a drug, people must avoid falling back into a pattern of misuse. As an aid to resisting temptation, some people with substance use disorders are given antagonist drugs, which block or change the effects of the addictive drug. Disulfiram (Antabuse), for example, is often given to people who are trying to stay away from alcohol. By itself, a low dose of disulfiram seems to have few negative effects, but a person who drinks alcohol while taking it will have intense nausea, vomiting, blushing, a faster heart rate, dizziness, and perhaps fainting. People taking disulfiram are less likely to drink alcohol because they know the terrible reaction that awaits them should they have even one drink. Disulfiram has proved helpful, but again only with people who are motivated to take it as prescribed (Diclemente et al., 2008).

For substance use disorders centered on opioids, several narcotic antagonists, such as naloxone, are used (Alter, 2014). These antagonists attach to endorphin receptor sites throughout the brain and make it impossible for the opioids to have their usual effect. Without the rush or high, continued drug use becomes pointless. Although narcotic antagonists have been helpful—particularly in emergencies, to rescue people from an overdose of opioids—they can in fact be dangerous for people who are addicted to opioids. The antagonists must be given very carefully because of their ability to throw such persons into severe withdrawal. Research indicates that narcotic antagonists may also be useful in the treatment of substance use disorders involving alcohol or cocaine (Crits-Christoph et al., 2015; Harrison & Petrakis, 2011).

methadone maintenance program A treatment approach in which clients are given legally and medically supervised doses of methadone—a heroin substitute—to treat heroin-centered substance use disorder.

Pros and cons of methadone treatment Methadone is itself a narcotic that can be as dangerous as other opioids when not taken under safe medical supervision. Here a couple protests against a proposed methadone treatment facility in Maine. Their 19-year-old daughter, who was not an opioid addict, had died months earlier after taking methadone to get high.

Drug Maintenance Therapy A drug-related lifestyle may be a bigger problem than the drug’s direct effects. Much of the damage caused by heroin addiction, for example, comes from overdoses, unsterilized needles, and an accompanying life of crime. Thus clinicians were very enthusiastic when methadone maintenance programs were developed in the 1960s to treat heroin addiction (Dole & Nyswander, 1967, 1965). In these programs, people with an addiction are given the laboratory opioid methadone as a substitute for heroin. Although they then become dependent on methadone, their new addiction is maintained under safe medical supervision. Unlike heroin, methadone produces a moderate high, can be taken by mouth (thus eliminating the dangers of needles), and needs to be taken only once a day.

Page 339

Why has the legal, medically supervised use of heroin (in Great Britain) or heroin substitutes (in the United States) sometimes failed to combat drug problems?

At first, methadone programs seemed very effective, and many of them were set up throughout the United States, Canada, and England. These programs became less popular during the 1980s, however, because of the dangers of methadone itself. Many clinicians came to believe that substituting one addiction for another is not an acceptable “solution” for a substance use disorder, and many people with an addiction complained that methadone addiction was creating an additional drug problem that simply complicated their original one (Winstock, Lintzeris, & Lea, 2011). Methadone is sometimes harder to withdraw from than heroin because the withdrawal symptoms can last longer (Hart & Ksir, 2014; Day & Strang, 2011). Moreover, pregnant women maintained on methadone have the added concern of the drug’s effect on their fetus.

Despite such concerns, maintenance treatment with methadone—or with other opioid substitute drugs—has again sparked interest among clinicians in recent years, partly because of new research support (Balhara, 2014; Fareed et al., 2011) and partly because of the rapid spread of the HIV and hepatitis C viruses among intravenous drug abusers and their sex partners and children (Lambdin et al., 2014; Galanter & Kleber, 2008). Not only is methadone treatment safer than street opioid use, but many methadone programs now include AIDS education and other health instructions in their services. Research suggests that methadone maintenance programs are most effective when they are combined with education, psychotherapy, family therapy, and employment counseling (Jhanjee, 2014). Today thousands of clinics provide methadone treatment across the United States.

Sociocultural Therapies

As you have read, sociocultural theorists—both family-social and multicultural theorists—believe that psychological problems emerge in a social setting and are best treated in a social context. Three sociocultural approaches have been used to help people overcome substance use disorders: (1) self-help programs, (2) culture- and gender-sensitive programs, and (3) community prevention programs.

48% of current AA members have been sober for more than five years.

37% of current AA members have been sober for less than one year.

(AA World Services, 2014)

Self-Help and Residential Treatment Programs Many people with substance use disorders have organized among themselves to help one another recover without professional assistance. The drug self-help movement dates back to 1935, when two Ohio men suffering from alcoholism met and wound up discussing alternative treatment possibilities. The first discussion led to others and to the eventual formation of a self-help group whose members discussed alcohol-related problems, traded ideas, and provided support. The organization became known as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA).

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) A self-help organization that provides support and guidance for people with alcohol use disorder.

Today AA has more than 2 million members in 114,000 groups across the world (AA World Services, 2014). It offers peer support along with moral and spiritual guidelines to help people overcome alcoholism. Different members apparently find different aspects of AA helpful. For some it is the peer support; for others it is the spiritual dimension (Tusa & Burgholzer, 2013). Meetings take place regularly, and members are available to help each other 24 hours a day.

Page 340

By offering guidelines for living, the organization helps members abstain “one day at a time,” urging them to accept as fact the ideas that they have a disease, are powerless over alcohol, and must stop drinking entirely and permanently if they are to live normal lives. Related self-help organizations, Al-Anon and Alateen, offer support for people who live with and care about people with alcoholism. Self-help programs such as Narcotics Anonymous and Cocaine Anonymous have been developed for other substance use disorders.

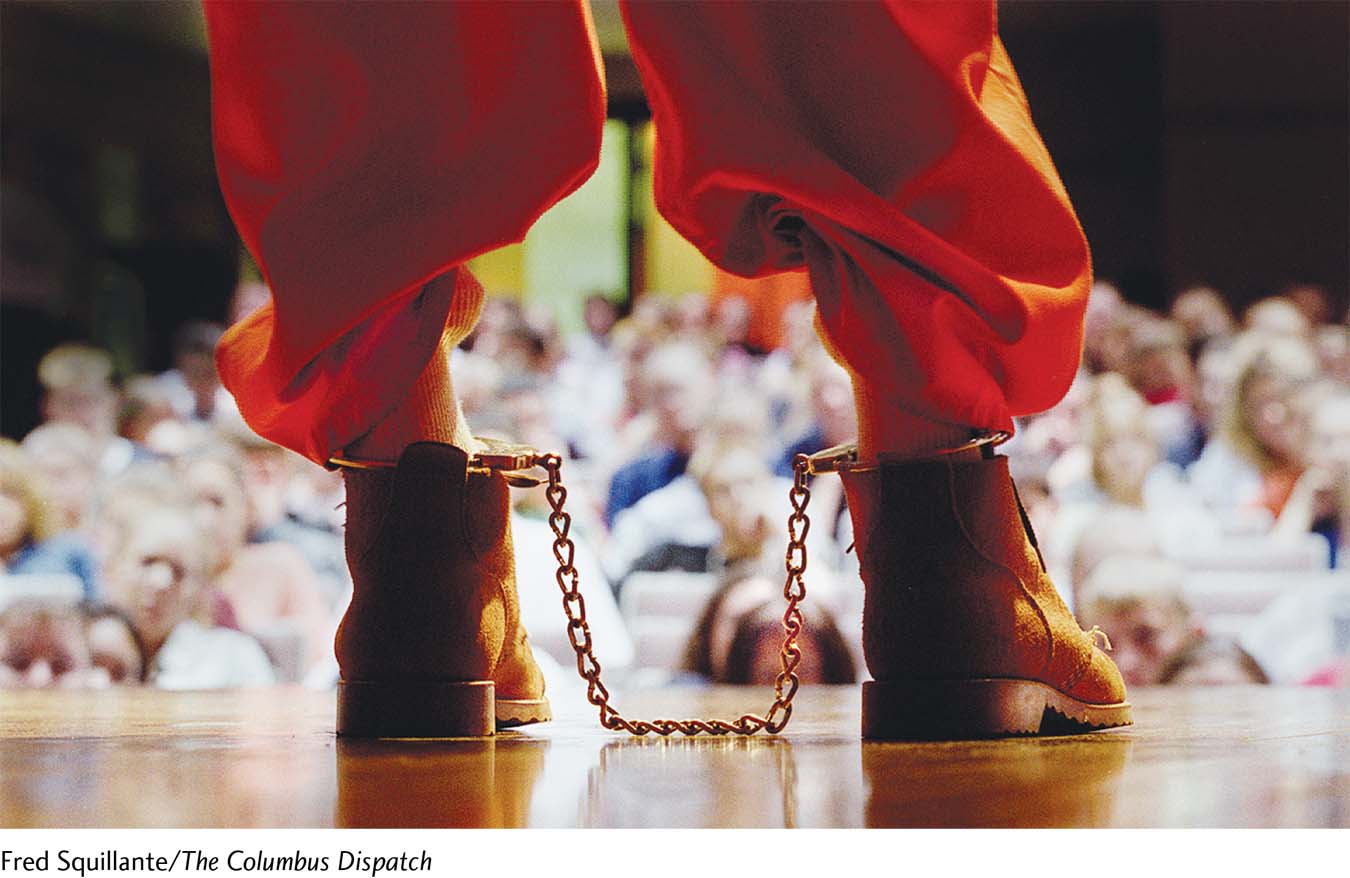

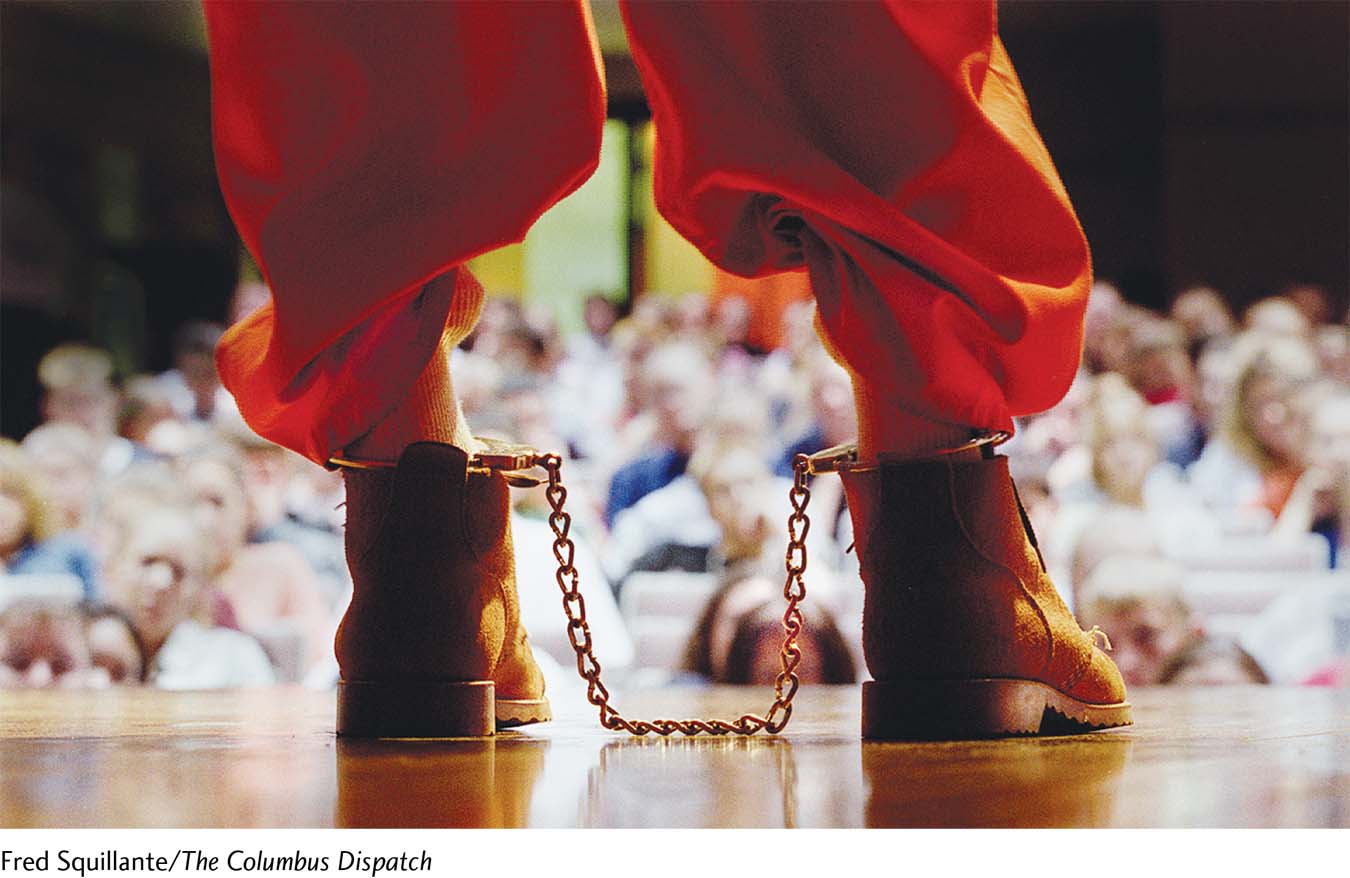

Fighting drug abuse while in prison Inmates at a county jail in Texas exercise and meditate as part of a drug and alcohol rehabilitation program. The program also includes psychoeducation and other interventions to help inmates address their substance use disorders.

It is worth noting that the abstinence goal of AA directly opposes the controlled-drinking goal of relapse-prevention training and several other interventions for substance misuse (see page 337). In fact, this issue—abstinence versus controlled drinking—has been debated for years (Hart & Ksir, 2014; Rosenthal, 2011, 2005). Feelings about it have run so strongly that in the 1980s the people on one side challenged the motives and honesty of those on the other (Sobell & Sobell, 1984, 1973; Pendery et al., 1982).

Research indicates, however, that both controlled drinking and abstinence may be useful treatment goals, depending on the nature of the particular drinking problem. Studies suggest that abstinence may be a more appropriate goal for people who have a long-standing alcohol use disorder, whereas controlled drinking can be helpful to younger drinkers whose pattern does not include tolerance and withdrawal reactions. Many of those in the latter group may respond to treatments that teach a nonabusive form of drinking (Hart & Ksir, 2014; Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2007, 2004).

residential treatment center A place where people formerly addicted to drugs live, work, and socialize in a drug-free environment. Also called a therapeutic community.

Many self-help programs have expanded into residential treatment centers, or therapeutic communities—such as Daytop Village and Phoenix House—where people formerly addicted to drugs live, work, and socialize in a drug-free environment while undergoing individual, group, and family therapies and making a transition back to community life (Relf et al., 2014; Bonetta, 2010).

The evidence that keeps self-help and residential treatment programs going comes largely in the form of individual testimonials. Many tens of thousands of people have revealed that they are members of these programs and credit them with turning their lives around. Studies of the programs have also had favorable findings, but their numbers have been limited (Galanter, 2014).

What different kinds of issues might be confronted by drug abusers from different minority groups or genders?

Culture- and Gender-Sensitive Programs Many people with substance use disorders live in a poor and perhaps violent setting. A growing number of today’s treatment programs try to be sensitive to the special sociocultural pressures and problems faced by drug abusers who are poor, homeless, or members of minority groups (Hadland & Baer, 2014; Hurd et al., 2014). Therapists who are sensitive to their clients’ life challenges can do more to address the stresses that often lead to relapse.

Similarly, therapists have become more aware that women often require treatment methods different from those designed for men (Lund, Brendryen, & Ravndal, 2014; Greenfield et al., 2011). Women and men often have different physical and psychological reactions to drugs, for example. In addition, treatment of women with substance use disorders may be complicated by the impact of sexual abuse, the possibility that they may be or may become pregnant while taking drugs, the stresses of raising children, and the fear of criminal prosecution for abusing drugs during pregnancy (Finnegan & Kandall, 2008). Thus many women with such disorders feel more comfortable seeking help at gender-sensitive clinics or residential programs; some such programs also allow children to live with their recovering mothers.

Page 341

Listen to my story A prisoner stands shackled before students at an Ohio high school and discusses his drunk-driving conviction (his intoxicated driving resulted in a fatal automobile crash). These visits by inmates are part of the school’s “Make the Right Choice” prevention program.

Community Prevention Programs Perhaps the most effective approach to substance use disorders is to prevent them (Sandler et al., 2014). The first drug-prevention programs were conducted in schools (Espada et al., 2015). Today such programs are also offered in workplaces, activity centers, and other community settings and even through the media (NSDUH, 2013). Around 75 percent of adolescents report that they have seen or heard a substance use–prevention message within the past year. And almost 60 percent have talked to their parents in the past year about the dangers of alcohol and other drugs.

What impact might admissions by celebrities about their past drug use have on people’s willingness to seek treatment?

Prevention programs may focus on the individual (for example, by providing education about unpleasant drug effects), the family (by teaching parenting skills), the peer group (by teaching resistance to peer pressure), the school (by setting up firm enforcement of drug policies), or the community at large. The most effective prevention efforts focus on several of these areas to provide a consistent message about drug misuse in all areas of people’s lives (Wambeam et al., 2014). Some prevention programs have even been developed for preschool children.

Two of today’s leading community-based prevention programs are TheTruth.com and Above the Influence. The Truth.com is an antismoking campaign, aimed at young people in particular, that has “edgy” ads on the Web (on YouTube, for instance), on television, and in magazines and newspapers. Above the Influence is a similar advertising campaign that focuses on a range of substances abused by teenagers. One recent nationwide survey of 3,000 students has suggested that watching Above the Influence ads may help reduce marijuana use by teenagers (Slater et al., 2011). The survey found that 8 percent of eighth-graders familiar with the campaign have taken up marijuana use, in contrast to 12 percent of students who have never seen the ads.

Cocaine accounts for more drug treatment admissions than any other drug (Hart & Ksir, 2014; SAMHSA, 2014).

Summing Up

HOW ARE SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS TREATED? Treatments for substance use disorders vary widely. Usually several approaches are combined. Psychodynamic therapies are used to try to help clients become aware of and correct the underlying needs and conflicts that may have led to their use of drugs. A common behavioral technique is aversion therapy, in which an unpleasant stimulus is paired with the drug that the person is abusing. Cognitive and behavioral techniques have been combined in such forms as relapse-prevention training. Biological treatments include detoxification, antagonist drugs, and drug maintenance therapy. Sociocultural treatments approach substance use disorders in a social context by means of self-help groups (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous), culture- and gender-sensitive treatments, and community prevention programs.