Chapter 4 Introduction

CHAPTER 4

TOPIC OVERVIEW

The Sociocultural Perspective: Societal and Multicultural Factors

The Psychodynamic Perspective

The Humanistic Perspective

The Cognitive Perspective

The Biological Perspective

Specific Phobias

Agoraphobia

What Causes Phobias?

How Are Phobias Treated?

What Causes Social Anxiety Disorder?

Treatments for Social Anxiety Disorder

The Biological Perspective

The Cognitive Perspective

What Are the Features of Obsessions and Compulsions?

The Psychodynamic Perspective

The Behavioral Perspective

The Cognitive Perspective

The Biological Perspective

Obsessive-

Anxiety, Obsessive-

Tomas, a 25-

He started therapy with Dr. Adena Morven, a clinical psychologist. Dr. Morven immediately noticed how disturbed Tomas appeared. He looked tense and frightened and could not sit comfortably in his chair; he kept tapping his feet and jumped when he heard traffic noise from outside the office building. He kept sighing throughout the visit, fidgeting and shifting his position, and he appeared breathless while telling Dr. Morven about his difficulties.

Tomas described his frequent inability to concentrate to the therapist. When designing client Web sites, he would lose his train of thought. Less than 5 minutes into a project, he’d forget much of his overall strategy. During conversations, he would begin a sentence and then forget the point he was about to make. TV watching had become impossible. He found it almost impossible to concentrate on anything for more than 5 minutes; his mind kept drifting away from the task at hand.

To say the least, he was worried about all of this. “I’m worried about being so worried,” he told Dr. Morven, almost laughing at his own remark. At this point, Tomas expected the worst whenever he began a conversation, task, plan, or outing. If an event or interaction did in fact start to go awry, he would find himself overwhelmed with uncomfortable feelings—

Typically, such physical reactions lasted but a matter of seconds. However, those few seconds felt like an eternity to Tomas. He acknowledged coming back down to earth after those feelings subsided—

Dr. Morven empathized with Tomas about how upsetting this all must be. She asked him why he had decided to come into therapy now—

fear The central nervous system’s physiological and emotional response to a serious threat to one’s well-

anxiety The central nervous system’s physiological and emotional response to a vague sense of threat or danger.

You don’t need to be as troubled as Tomas to experience fear and anxiety. Think about a time when your breathing quickened, your muscles tensed, and your heart pounded with a sudden sense of dread. Was it when your car almost skidded off the road in the rain? When your professor announced a pop quiz? What about when the person you were in love with went out with someone else or your boss suggested that your job performance ought to improve? Any time you face what seems to be a serious threat to your well-

If fear is so unpleasant, why do many people seek out the feelings of fear brought about by amusement park rides, scary movies, bungee jumping, and the like?

Although everyday experiences of fear and anxiety are not pleasant, they often are useful. They prepare us for action—

Anxiety disorders are the most common mental disorders in the United States. In any given year around 18 percent of the adult population suffer from one or another of the anxiety disorders identified by DSM-

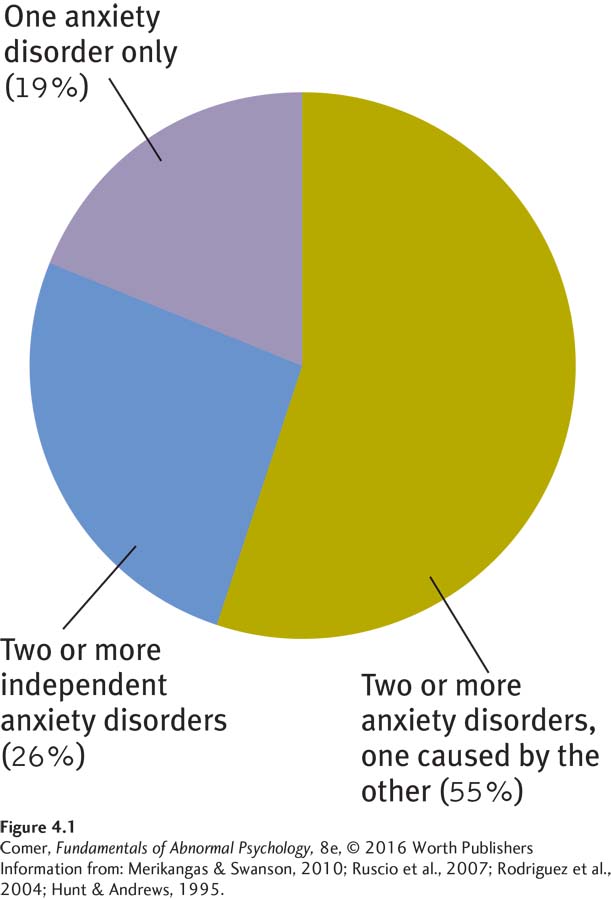

People with generalized anxiety disorder experience general and persistent feelings of worry and anxiety. People with specific phobias have a persistent and irrational fear of a particular object, activity, or situation. People with agoraphobia fear traveling to public places such as stores or movie theaters. Those with social anxiety disorder are intensely afraid of social or performance situations in which they may become embarrassed. And people with panic disorder have recurrent attacks of terror. Most individuals with one anxiety disorder suffer from a second one as well (Leyfer et al., 2013; Merikangas & Swanson, 2010) (see Figure 4.1). Tomas, for example, has the excessive worry found in generalized anxiety disorder and the repeated attacks of terror that mark panic disorder. In addition, many of those with an anxiety disorder also experience depression (Starr et al., 2014).

Anxiety also plays a major role in a different group of problems, called obsessive-