12.3 How Are Schizophrenia and Other Severe Mental Disorders Treated?

BETWEEN THE LINES

Treatment Delay

The average length of time between the first appearance of psychotic symptoms and the initiation of treatment is more than one year (Addington et al., 2015).

Today’s treatment picture for schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders is marked by miraculous triumphs for some, modest success for others, and heartbreaking failure for still others. It is typically characterized by medications, medication-

Let us look at the case of Cathy, whose journey is typical of that of hundreds of thousands of people with schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders. To be sure, there are other patients whose efforts to overcome schizophrenia go more smoothly. And at the other end of the spectrum, there are many whose struggles against severe mental dysfunctioning never come close to Cathy’s level of success. In between, there are the Cathys.

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“I shouldn’t precisely have chosen madness if there had been any choice, but once such a thing has taken hold of you, you can’t very well get out of it.”

Vincent van Gogh, 1889

During [her] second year in college ….er emotional troubles worsened…. and [Cathy was] put on Haldol and lithium.

For the next sixteen years, Cathy cycled in and out of hospitals. She “hated the meds”—Haldol stiffened her muscles and caused her to drool, while the lithium made her depressed—

In early 1994, she was hospitalized for the fifteenth time. She was seen as chronically mentally ill, occasionally heard voices now ….nd was on a cocktail of drugs: Haldol, Ativan, Tegretol, Halcion, and Cogentin, the last drug an antidote to Haldol’s nasty side effects. But after she was released that spring, a psychiatrist told her to try Risperdal, a new antipsychotic that had just been approved by the FDA. “Three weeks later, my mind was much clearer,” she says. “The voices were going away. I got off the other meds and took only this one drug. I got better. I could start to plan. I wasn’t talking to the devil anymore. Jesus and God weren’t battling it out in my head.” Her father put it this way: “Cathy is back.” …

She went back to school and earned a degree in radio, film, and television…. In 1998, she began dating the man she lives with today…. In 2005, she took a part-

Risperdal has also taken a physical toll…. She has ….eveloped some of the metabolic problems, such as high cholesterol, that the atypical antipsychotics regularly cause. “I can go toe-

Such has been her life’s course on medications. Sixteen terrible years, followed by fourteen pretty good years on Risperdal. She believes that this drug is essential to her mental health today, and indeed, she could be seen as a local poster child for promoting the wonders of that drug. Still, if you look at the long-

Cathy believes that this is a question that psychiatrists never contemplate.

“They don’t have any sense about how these drugs affect you over the long term. They just try to stabilize you for the moment, and look to manage you from week to week, month to month. That’s all they ever think about.”

(Whitaker, 2010)

As Cathy’s journey illustrates, schizophrenia is extremely difficult to treat, but clinicians are much more successful at doing so today than they were in the past. Much of the credit goes to antipsychotic drugs—imperfect, troubling, and even dangerous though they may be. These medications help many people with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders to think clearly and to profit from psychotherapies that previously would have had little effect for them (Skelton et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2012).

To best convey the plight of people with schizophrenia, this chapter will depart from the usual format and discuss the treatments from a historical perspective. A look at how treatment has changed over the years will help us understand the nature, problems, and promise of today’s approaches. As we consider past treatments for schizophrenia, it is important to keep in mind that throughout much of the twentieth century the label “schizophrenia” was assigned to most people with psychosis. Clinical theorists now realize that many people with psychotic symptoms are instead experiencing a severe form of bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder and that such people were in past times inaccurately diagnosed with schizophrenia (Tondo et al., 2015; Lake, 2012). Thus, our discussions of past treatments for schizophrenia, particularly the failures of institutional care, are as applicable to those other severe mental disorders as they are to schizophrenia. Similarly, our discussions about current approaches to schizophrenia, such as the community mental health movement, often apply to other severe mental disorders as well.

Institutional Care in the Past

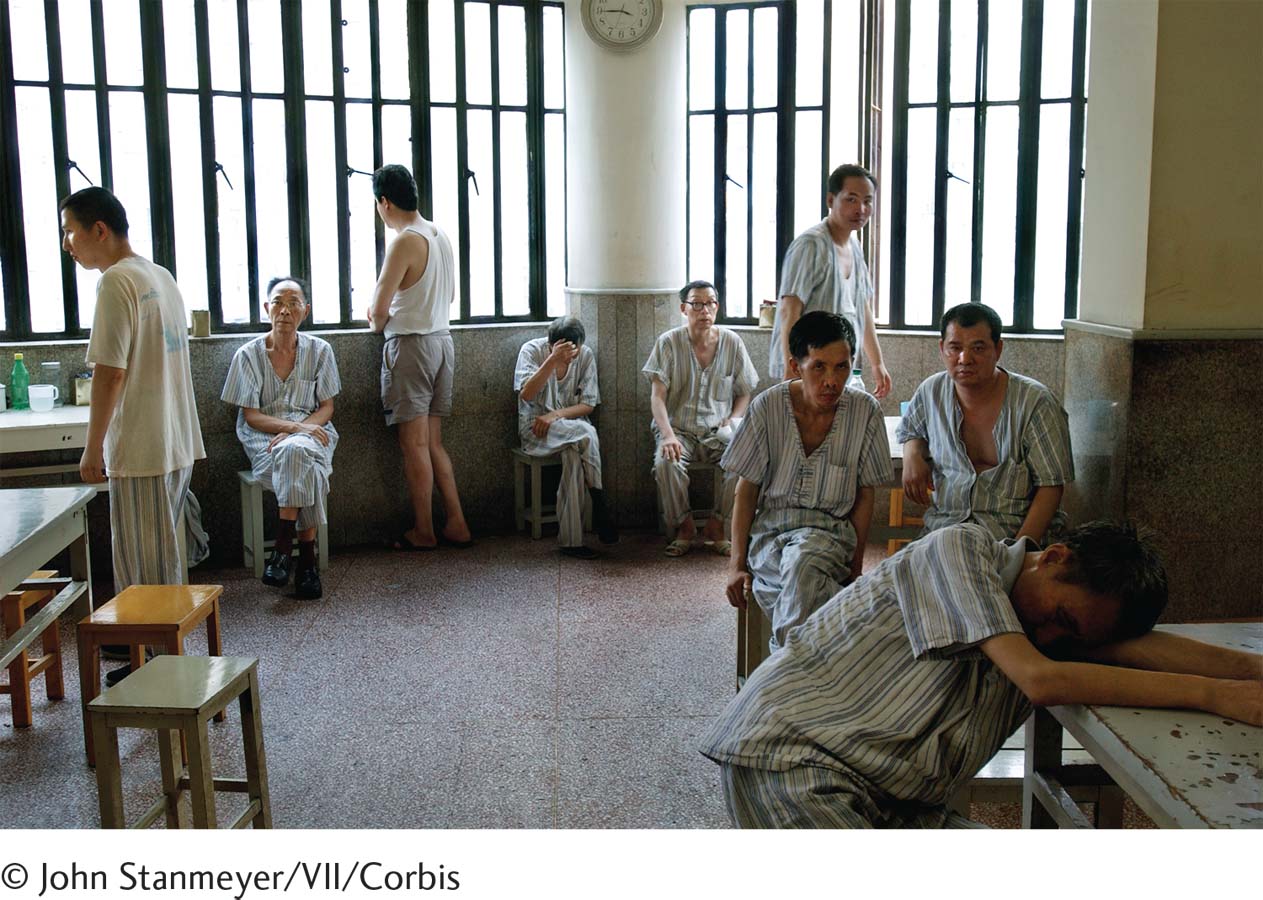

For more than half of the twentieth century, most people diagnosed with schizophrenia were institutionalized in a public mental hospital. Because patients with schizophrenia did not respond to traditional therapies, the primary goals of these hospitals were to restrain them and give them food, shelter, and clothing. Patients rarely saw therapists and generally were neglected. Many were abused. Oddly enough, this state of affairs unfolded in an atmosphere of good intentions.

As you read in Chapter 1, the move toward institutionalization in hospitals began in 1793 when French physician Philippe Pinel “unchained the insane” at La Bicêtre asylum and began the practice of “moral treatment.” For the first time in centuries, patients with severe disturbances were viewed as human beings who should be cared for with sympathy and kindness. As Pinel’s ideas spread throughout Europe and the United States, they led to the creation of large mental hospitals rather than asylums to care for those with severe mental disorders (Goshen, 1967).

state hospitals Public mental hospitals in the United States, run by the individual states.

These new mental hospitals, typically located in isolated areas where land and labor were cheap, were meant to protect patients from the stresses of daily life and offer them a healthful psychological environment in which they could work closely with therapists (Grob, 1966). States throughout the United States were even required by law to establish public mental institutions, state hospitals, for patients who could not afford private ones.

Eventually, however, the state hospital system encountered serious problems. Between 1845 and 1955, nearly 300 state hospitals opened in the United States, and the number of hospitalized patients on any given day rose from 2,000 in 1845 to nearly 600,000 in 1955. During this expansion, wards became overcrowded, admissions kept rising, and state funding was unable to keep up.

Why have people with schizophrenia so often been victims of horrific treatments such as overcrowded wards, lobotomy, and, later, deinstitutionalization?

The priorities of the public mental hospitals, and the quality of care they provided, changed over those 110 years. In the face of overcrowding and understaffing, the emphasis shifted from giving humanitarian care to keeping order. In a throwback to the asylum period, difficult patients were restrained, isolated, and punished; individual attention disappeared. Patients were transferred to back wards, or chronic wards, if they failed to improve quickly (Bloom, 1984). Most of the patients on these wards suffered from schizophrenia (Häfner & an der Heiden, 1988). The back wards were human warehouses filled with hopelessness. Staff members relied on straitjackets and handcuffs to deal with difficult patients. More “advanced” forms of treatment included medical approaches such as lobotomy (see PsychWatch below). Many patients not only failed to improve under these conditions but also developed additional symptoms, apparently as a result of institutionalization itself.

Institutional Care Takes a Turn for the Better

In the 1950s, clinicians developed two institutional approaches that finally brought some hope to patients who had lived in institutions for years: milieu therapy, based on humanistic principles, and the token economy program, based on behavioral principles. These approaches particularly helped improve the personal care and self-

milieu therapy A humanistic approach to institutional treatment based on the premise that institutions can help patients recover by creating a climate that promotes self-

Milieu Therapy In 1953, Maxwell Jones, a London psychiatrist, converted a ward of patients with various psychological disorders into a therapeutic community—

Since Jones’ pioneering effort, milieu-

Research over the years has shown that people with schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders in milieu hospital programs often improve and that they leave the hospital at higher rates than patients in programs offering primarily custodial care (Paul, 2000; Paul & Lentz, 1977). Many remain impaired, however, and must live in sheltered settings after their release. Despite its limitations, milieu therapy continues to be practiced in many institutions, often combined with other hospital approaches (Borge et al., 2013). Moreover, you will see later in this chapter that many of today’s halfway houses and other community programs for people with severe mental disorders apply the principles of milieu therapy.

PsychWatch

Lobotomy: How Could It Happen?

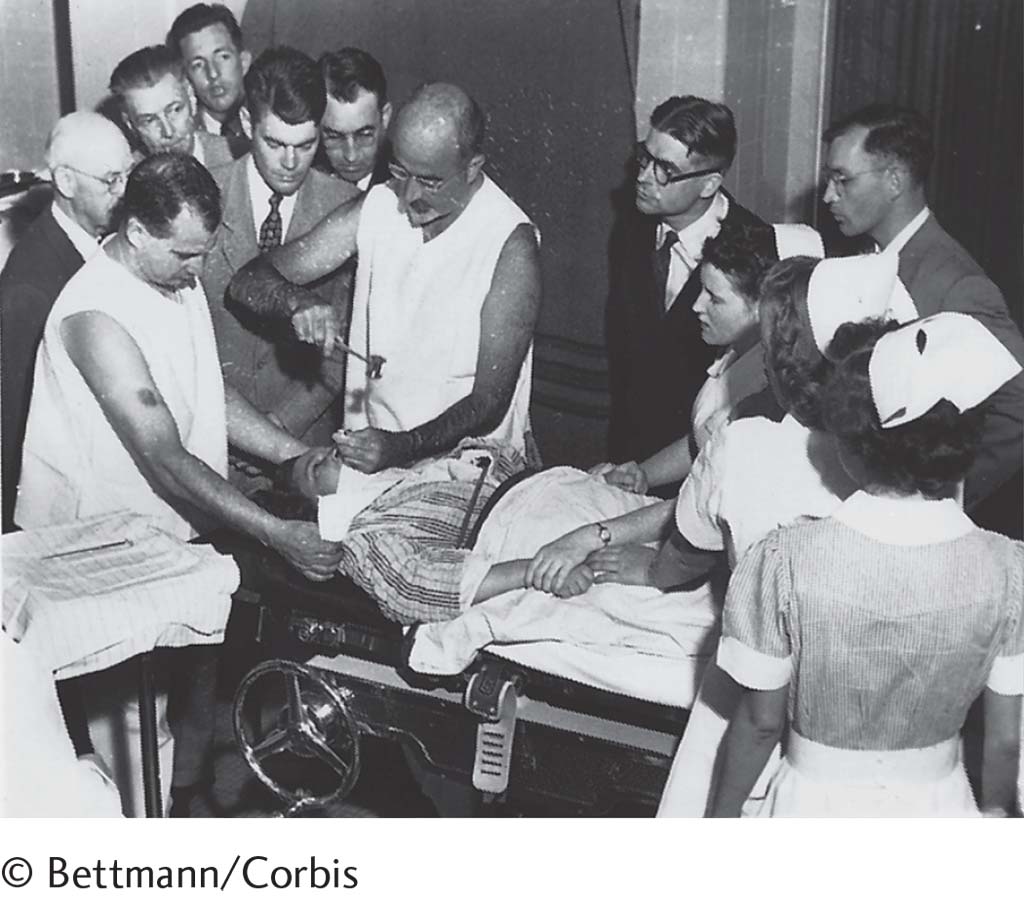

In 1935, a Portuguese neurologist named Egas Moniz performed a revolutionary new surgical procedure, which he called a prefrontal leucotomy, on a patient with severe mental dysfunctioning (Raz, 2013). The procedure, the first form of lobotomy, consisted of drilling two holes in either side of the skull and inserting an instrument resembling an icepick into the brain tissue to cut or destroy nerve fibers. Moniz believed that severe abnormal thinking—

After Moniz published a monograph describing 20 leucotomies that he had performed, an American neurologist, Walter Freeman, called the procedure to the attention of the medical community in the United States and performed it on many patients (Raz, 2013). In 1947 Freeman further developed a second kind of lobotomy called the transorbital lobotomy, in which the surgeon inserted a needle into the brain through the eye socket and rotated it in order to destroy the brain tissue.

From the early 1940s through the mid-

We now know that the lobotomy was hardly a miracle treatment. Far from “curing” people with mental disorders, the procedure left thousands upon thousands extremely withdrawn, subdued, and even stuporous. Why then was the procedure so enthusiastically accepted by the medical community in the 1940s and 1950s? Neuroscientist Elliot Valenstein (1986) points first to the extreme overcrowding in mental hospitals at the time. This crowding was making it difficult to maintain decent standards in the hospitals. Valenstein also points to the personalities of the inventors of the procedure as important factors. Although they were highly regarded, gifted, and dedicated physicians—

For years, physicians throughout the world were apparently misled by the seemingly positive findings of early studies of the lobotomy, which, as it turned out, were not based on sound methodology (Cooper, 2014). By the 1950s, however, better studies revealed that in addition to having a fatality rate of 1.5 to 6 percent, lobotomies could cause serious problems such as brain seizures, huge weight gain, loss of motor coordination, partial paralysis, incontinence, endocrine malfunctions, and very poor intellectual and emotional responsiveness (Lapidus et al., 2013). The discovery of effective antipsychotic drugs helped put an end to this inhumane treatment for mental disorders (Krack et al., 2010).

Today’s psychosurgical procedures are greatly refined, used only as a last resort for various severe disorders, and hardly resemble the lobotomies of 60 years back (Nair et al., 2014; Lapidus et al., 2013). Even so, many professionals believe that any kind of surgery that destroys brain tissue is inappropriate and perhaps unethical and that it keeps alive one of the clinical field’s most shameful and ill-

token economy program A behavioral program in which a person’s desirable behaviors are reinforced systematically throughout the day by the awarding of tokens that can be exchanged for goods or privileges.

The Token Economy In the 1950s, behaviorists discovered that the systematic use of operant conditioning techniques on hospital wards could help change the behaviors of patients (Ayllon, 1963; Ayllon & Michael, 1959). Programs that apply these techniques are called token economy programs.

In token economies, patients are rewarded when they behave acceptably and are not rewarded when they behave unacceptably. The immediate rewards for acceptable behavior are often tokens that can later be exchanged for food, cigarettes, hospital privileges, and other desirable items, all of which compose a “token economy.” Acceptable behaviors likely to be included are caring for oneself and for one’s possessions (making the bed, getting dressed), going to a work program, speaking normally, following ward rules, and showing self-

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“I believe that if you grabbed the nearest normal person off the street and put them in a psychiatric hospital, they’d be diagnosable as mad within weeks.”

Clare Allan, novelist, Poppy Shakespeare

Some clinicians have questioned the quality of the improvements made under token economy programs. Are behaviorists changing a patient’s psychotic thoughts and perceptions or simply improving the patient’s ability to imitate normal behavior? This issue is illustrated by the case of a middle-

We’re tired of it. Every damn time we want a cigarette, we have to go through their bullshit. “What’s your name? Who wants the cigarette? Where is the government?” Today, we were desperate for a smoke and went to Simpson, the damn nurse, and she made us do her bidding. “Tell me your name if you want a cigarette. What’s your name?” Of course, we said, “John.” We needed the cigarettes. If we told her the truth, no cigarettes. But we don’t have time for this nonsense. We’ve got business to do, international business, laws to change, people to recruit. And these people keep playing their games.

(Comer, 1973)

Critics of the behavioral approach would argue that John was still delusional and therefore as psychotic as before. Behaviorists, however, would argue that at the very least, John’s judgment about the consequences of his behavior had improved.

Token economy programs are no longer as popular as they once were, but they are still used in many mental hospitals, usually along with medication, and in many community residences as well (Kopelowicz et al., 2008). The approach has also been applied to other clinical problems, including intellectual disability, delinquency, and hyperactivity, as well as in other fields, such as education and business (Spiegler & Guevremont, 2015).

Antipsychotic Drugs

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“Men will always be mad and those who think they can cure them are the maddest of all.”

Voltaire (1694–

Milieu therapy and token economy programs helped improve the gloomy outlook for patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, but it was the discovery of antipsychotic drugs in the 1950s that truly revolutionized treatment for schizophrenia. These drugs eliminate many of its symptoms and today are almost always a part of treatment.

As you read earlier, the discovery of antipsychotic medications dates back to the 1940s, when researchers developed the first antihistamine drugs to combat allergies. The French surgeon Henri Laborit soon discovered that one group of antihistamines, phenothiazines, could also be used to help calm patients about to undergo surgery. Laborit suspected that the drugs might also have a calming effect on people with severe psychological disorders. One of the drugs, chlorpromazine, was eventually tested on six patients with psychotic symptoms and found to reduce their symptoms sharply. In 1954, chlorpromazine was approved for sale in the United States as an antipsychotic drug under the trade name Thorazine (Adams et al., 2014).

neuroleptic drugs Conventional antipsychotic drugs, so called because they often produce undesired effects similar to the symptoms of neurological disorders.

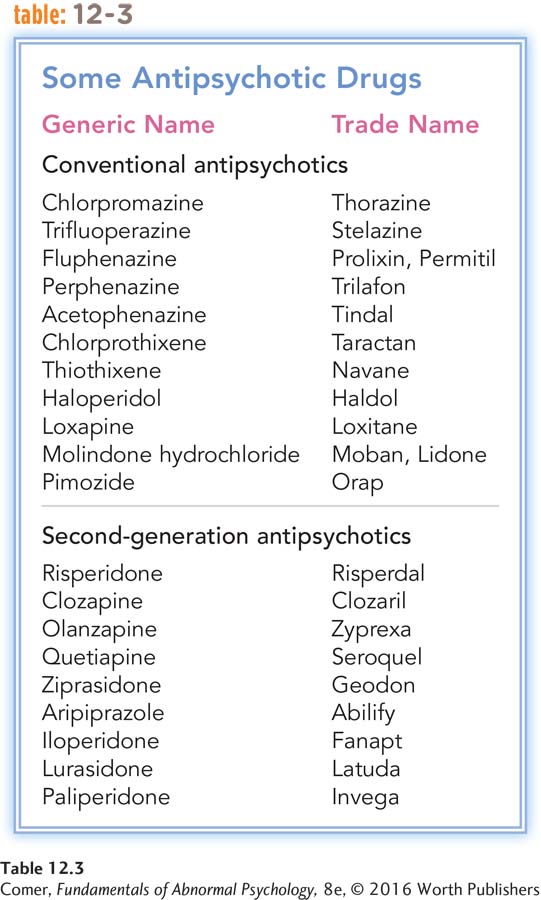

Since the discovery of the phenothiazines, other kinds of antipsychotic drugs have been developed. The ones developed throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s are now referred to as “conventional” antipsychotic drugs in order to distinguish them from the “second-

How Effective Are Antipsychotic Drugs? Research has shown that antipsychotic drugs reduce symptoms in at least 65 percent of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia (Advokat et al., 2014; Geddes et al., 2011). Moreover, in direct comparisons the drugs appear to be a more effective treatment for schizophrenia than any of the other approaches used alone, such as psychotherapy, milieu therapy, or electroconvulsive therapy. In most cases, the drugs produce at least some improvement within weeks (Rabinowitz et al., 2014); however, symptoms may return if the patients stop taking the drugs too soon (Razali & Yusoff, 2014). The antipsychotic drugs, particularly the conventional ones, reduce the positive symptoms of schizophrenia (such as hallucinations and delusions) more completely, or at least more quickly, than the negative symptoms (such as restricted affect, poverty of speech, and loss of volition) (Millan et al., 2014; Stroup et al., 2012).

extrapyramidal effects Unwanted movements, such as severe shaking, bizarre-

The Unwanted Effects of Conventional Antipsychotic Drugs In addition to reducing psychotic symptoms, the conventional antipsychotic drugs sometimes produce disturbing movement problems (Kinon et al., 2014; Stroup et al., 2012). These effects are called extrapyramidal effects because they appear to be caused by the drugs’ impact on the extrapyramidal areas of the brain, areas that help control motor activity.

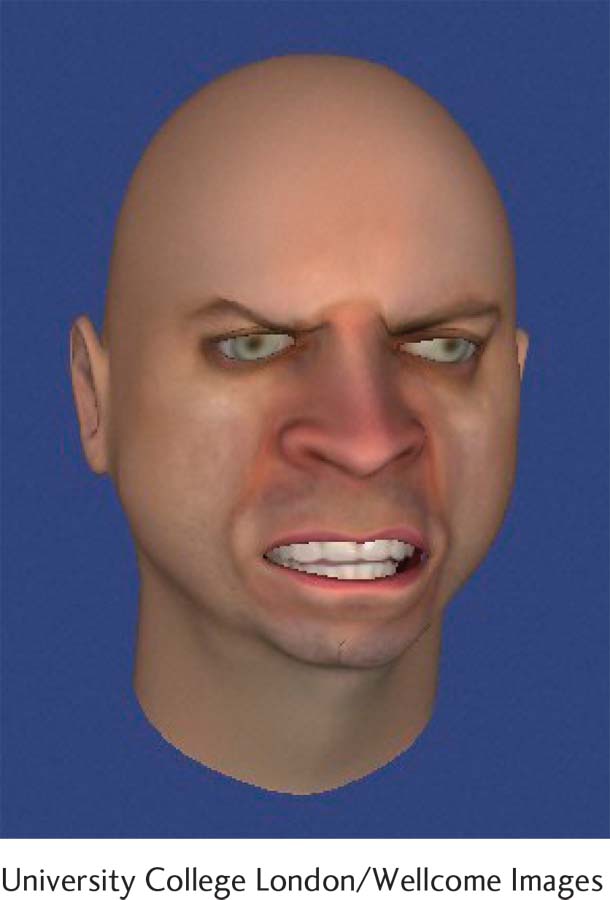

The most common extrapyramidal effects are Parkinsonian symptoms, reactions that closely resemble the features of the neurological disorder Parkinson’s disease. At least half of patients on conventional antipsychotic drugs have muscle tremors and muscle rigidity at some point in their treatment; they may shake, move slowly, shuffle their feet, and show little facial expression (Geddes et al., 2011; Haddad & Mattay, 2011). Some also have related symptoms such as movements of the face, neck, tongue, and back; and a number experience significant restlessness and discomfort in their limbs.

tardive dyskinesia Extrapyramidal effects involving involuntary movements that some patients have after they have taken conventional antipsychotic drugs for an extended time.

Whereas most undesired drug effects appear within days or weeks, a reaction called tardive dyskinesia (meaning “late-

Today clinicians are more knowledgeable and more cautious about prescribing conventional antipsychotic drugs than they were in the past (see Table 12.3). Previously, when patients did not improve with such a drug, their clinician would keep increasing the dose; today a clinician will typically add an additional drug to achieve a synergistic effect, stop the drug and try an alternative one, or stop all medications (Li et al., 2014; Roh et al., 2014). Today’s clinicians also try to prescribe the lowest effective doses for each patient and to gradually reduce medications weeks or months after the patient begins functioning normally (Takeuchi et al., 2014).

Newer Antipsychotic Drugs As you read earlier, second-

Second-

Given such advantages, more than half of all medicated patients with schizophrenia now take the second-

Psychotherapy

Before the discovery of antipsychotic drugs, psychotherapy was not really an option for people with schizophrenia. Most were too far removed from reality to profit from it. Today, however, psychotherapy is helpful to many such patients (Miller et al., 2012). By helping to relieve thought and perceptual disturbances, antipsychotic drugs allow many people with schizophrenia to learn about their disorder, participate actively in therapy (see MindTech below), think more clearly, make changes in their behavior, and cope with stressors in their lives. The most helpful forms of psychotherapy include cognitive-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Private Notions

Surveys suggest that 22 to 37 percent of people in the United States and Britain believe Earth has been visited by aliens from outer space.

Twenty percent of people worldwide believe that aliens walk on Earth disguised as humans.

(Reuters, 2010; Spanton, 2008; Andrews, 1998)

Cognitive-

With this explanation in mind, an increasing number of clinicians now employ a cognitive-

They provide clients with education and evidence about the biological causes of hallucinations.

They help clients learn more about the “comings and goings” of their own hallucinations and delusions. The clients learn, for example, to identify which kinds of events and situations trigger the voices in their heads.

The therapists challenge their clients’ inaccurate ideas about the power of their hallucinations, such as the idea that the voices are all-

powerful and uncontrollable and must be obeyed. The therapists also have the clients conduct behavioral experiments to put such notions to the test. What happens, for example, if the clients occasionally resist following the orders from their hallucinatory voices? The therapists teach clients to more accurately interpret their hallucinations. Clients may, for example, adopt alternative conclusions such as, “It’s not a real voice, it’s my illness.”

The therapists teach clients techniques for coping with their unpleasant sensations (hallucinations). The clients may, for example, learn ways to reduce the physical arousal that accompanies hallucinations—

using special breathing and relaxation techniques and the like. Similarly, they may learn to distract themselves whenever the hallucinations occur (Veiga- Martínez et al., 2008).

These behavioral and cognitive techniques often help schizophrenic people feel more control over their hallucinations and reduce their delusional ideas. Can anything be done further to lessen the hallucinations’ unpleasant impact on the person? Yes, say new-

As you read in Chapters 2 and 4, new-

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“If you talk to God, you are praying. If God talks to you, you have schizophrenia.”

Thomas Szasz, psychiatric theorist

Studies indicate that the various cognitive-

MindTech

Putting a Face on Auditory Hallucinations

Putting a Face on Auditory Hallucinations

In Chapter 2, you read that a growing number of therapists are using avatar therapy to help clients overcome their psychological problems. In this form of cybertherapy, therapists have the clients interact with computer-

For a pilot study, the researchers selected 16 participants who were being tormented by imaginary voices (auditory hallucinations). In each case, the therapist presented the patient with a mean-

The patient was placed alone in a room with the computer simulation while the therapist generated the on-

After seven 30-

Family Therapy More than 50 percent of those who are recovering from schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders live with their families: parents, siblings, spouses, or children (Tsai et al., 2011; Barrowclough & Lobban, 2008). Generally speaking, people with schizophrenia who feel positive toward their relatives do better in treatment (Okpokoro et al., 2014). As you saw earlier, recovered patients living with relatives who display high levels of expressed emotion—that is, relatives who are very critical, emotionally overinvolved, and hostile—

To address such issues, clinicians now commonly include family therapy in their treatment of schizophrenia, providing family members with guidance, training, practical advice, psychoeducation about the disorder, and emotional support and empathy. In family therapy, relatives develop more realistic expectations and become more tolerant, less guilt-

The families of people with schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders may also turn to family support groups and family psychoeducational programs for encouragement and advice (Duckworth & Halpern, 2014). In such programs, family members meet with others in the same situation to share their thoughts and emotions, provide mutual support, and learn about schizophrenia.

Social Therapy Many clinicians believe that the treatment of people with schizophrenia should include techniques that address social and personal difficulties in the clients’ lives. These clinicians offer practical advice; work with clients on problem solving, decision making, and social skills; make sure that the clients are taking their medications properly; and may even help them find work, financial assistance, appropriate health care, and proper housing (Granholm et al., 2014; Ordemann et al., 2014). Research finds that this practical, active, and broad approach, called social therapy or personal therapy, does indeed help keep people out of the hospital (Haddock & Spaulding, 2011; Hogarty, 2002).

The Community Approach

The broadest approach for the treatment of schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders is the community approach. In 1963, partly in response to the terrible conditions in public mental institutions and partly because of the emergence of antipsychotic drugs, the U.S. government ordered that patients be released and treated in the community. Congress passed the Community Mental Health Act, which provided that patients with psychological disorders were to receive a range of mental health services—

deinstitutionalization The discharge of large numbers of patients from long-

How might the “revolving door” pattern itself worsen the symptoms and outlook of people with schizophrenia?

Thus began several decades of deinstitutionalization, an exodus of hundreds of thousands of patients with schizophrenia and other long-

What Are the Features of Effective Community Care? People recovering from schizophrenia and other severe disorders need medication, psychotherapy, help in handling daily pressures and responsibilities, guidance in making decisions, social skills training, residential supervision, and vocational counseling—

community mental health center A treatment facility that provides medication, psychotherapy, and emergency care for psychological problems and coordinates treatment in the community.

COORDINATED SERVICES When the Community Mental Health Act was first passed, it was expected that community care would be provided by community mental health centers, treatment facilities that would supply medication, psychotherapy, and inpatient emergency care to people with severe disturbances, as well as coordinate the services offered by other community agencies. When community mental health centers are available and do provide these services, patients with schizophrenia and other severe disorders often make significant progress (Burns & Drake, 2011). Coordination of services is particularly important for so-

aftercare A program of posthospitalization care and treatment in the community.

SHORT-

day center A program that offers hospital-

PARTIAL HOSPITALIZATION People’s needs may fall between full hospitalization and outpatient therapy, and so some communities offer day centers, or day hospitals, all-

halfway house A residence for people with schizophrenia or other severe problems, often staffed by paraprofessionals. Also known as a group home or crisis house.

SUPERVISED RESIDENCES Many people do not require hospitalization but are unable to live alone or with their families. Halfway houses, also known as crisis houses or group homes, often serve individuals well (Lindenmayer & Khan, 2012). Such residences may shelter between one and two dozen people. Live-

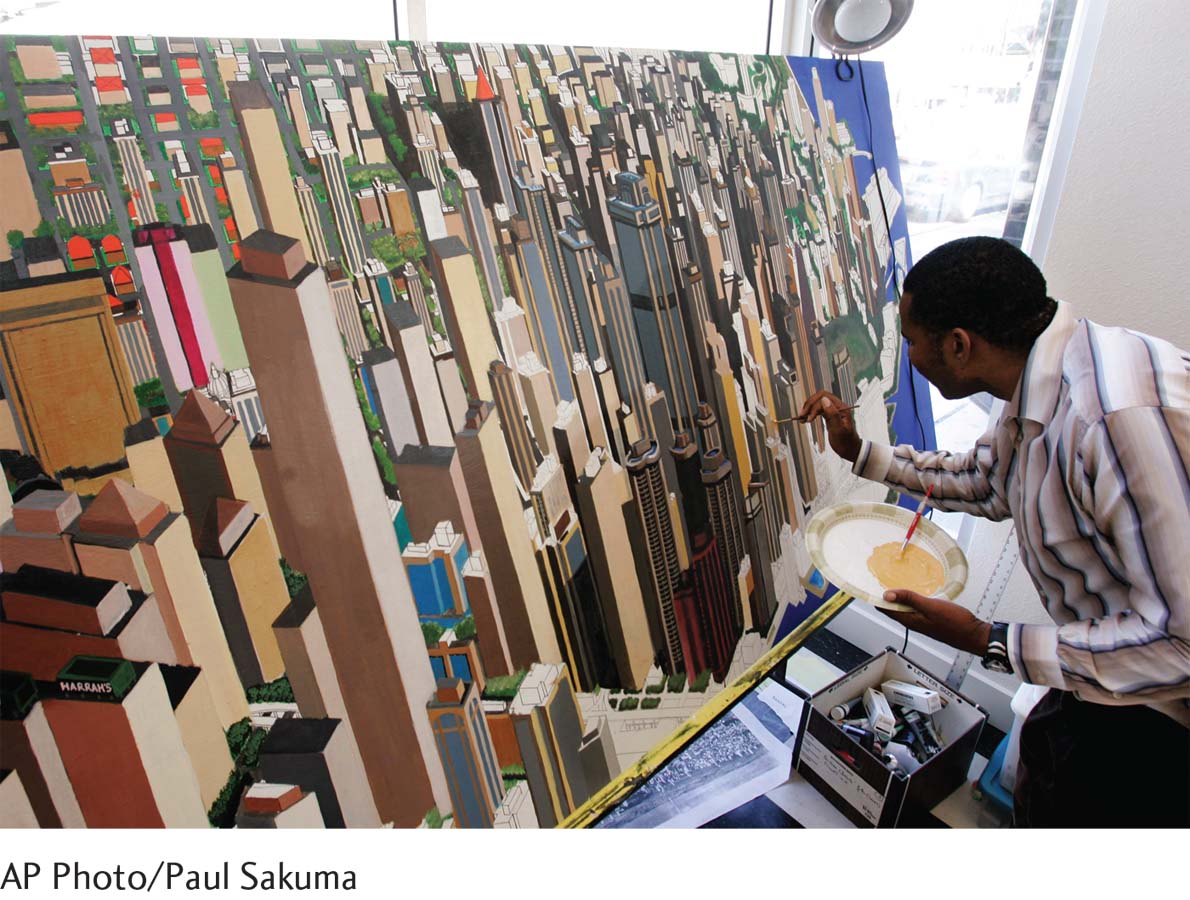

OCCUPATIONAL TRAINING AND SUPPORT Paid employment provides income, independence, self-

sheltered workshop A supervised workplace for people who are not yet ready for competitive jobs.

Many people recovering from such disorders receive occupational training in a sheltered workshop—a supervised workplace for employees who are not ready for competitive or complicated jobs. For some, the sheltered workshop becomes a permanent workplace. For others, it is an important step toward better-

An alternative work opportunity for people with severe psychological disorders is supported employment, in which vocational agencies and counselors help clients find competitive jobs in the community and provide psychological support while the clients are employed (Solar, 2014: Bell et al., 2011). Like sheltered workshops, supported employment opportunities are often in short supply.

How Has Community Treatment Failed? There is no doubt that effective community programs can help people with schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders recover. However, fewer than half of all the people who need them receive appropriate community mental health services (Addington et al., 2015; Burns & Drake, 2011). In fact, in any given year, 40 to 60 percent of all people with schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders receive no treatment at all (NIH, 2014; Torrey, 2001). Two factors are primarily responsible: poor coordination of services and a shortage of services.

POOR COORDINATION OF SERVICES The various mental health agencies in a community often fail to communicate with one another. There may be an opening at a nearby halfway house, for example, and the therapist at the community mental health center may not know about it. In addition, even within a community agency a patient may not have continuing contacts with the same staff members and may fail to receive consistent services. Still another problem is poor communication between state hospitals and community mental health centers, particularly at times of discharge (Torrey, 2001).

case manager A community therapist who offers a full range of services for people with schizophrenia or other severe disorders, including therapy, advice, medication, guidance, and protection of patients’ rights.

To help deal with such problems in communication and coordination, a growing number of community therapists have become case managers for people with schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders (Mas-

SHORTAGE OF SERVICES The number of community programs—

There are various reasons for this shortage of services. The primary one is economic (Feldman et al., 2014; Covell et al., 2011). On the one hand, more public funds are available for people with psychological disorders now than in the past. In 1963 a total of $1 billion was spent in this area, whereas today approximately $171 billion in public funding is devoted each year to people with mental disorders (Rampell, 2013; Gill, 2010; Redick et al., 1992). This represents a significant increase even when inflation and so-

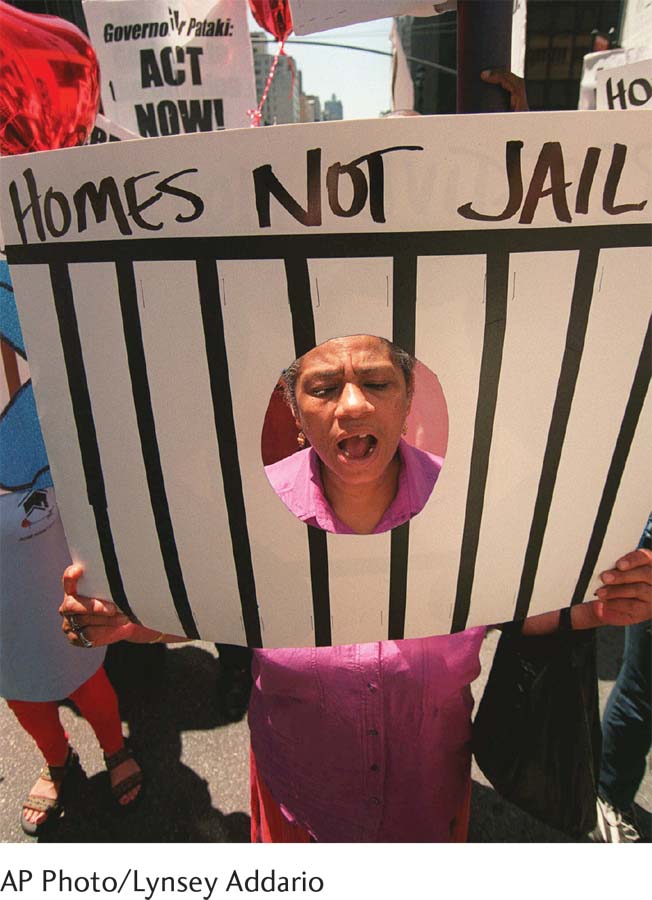

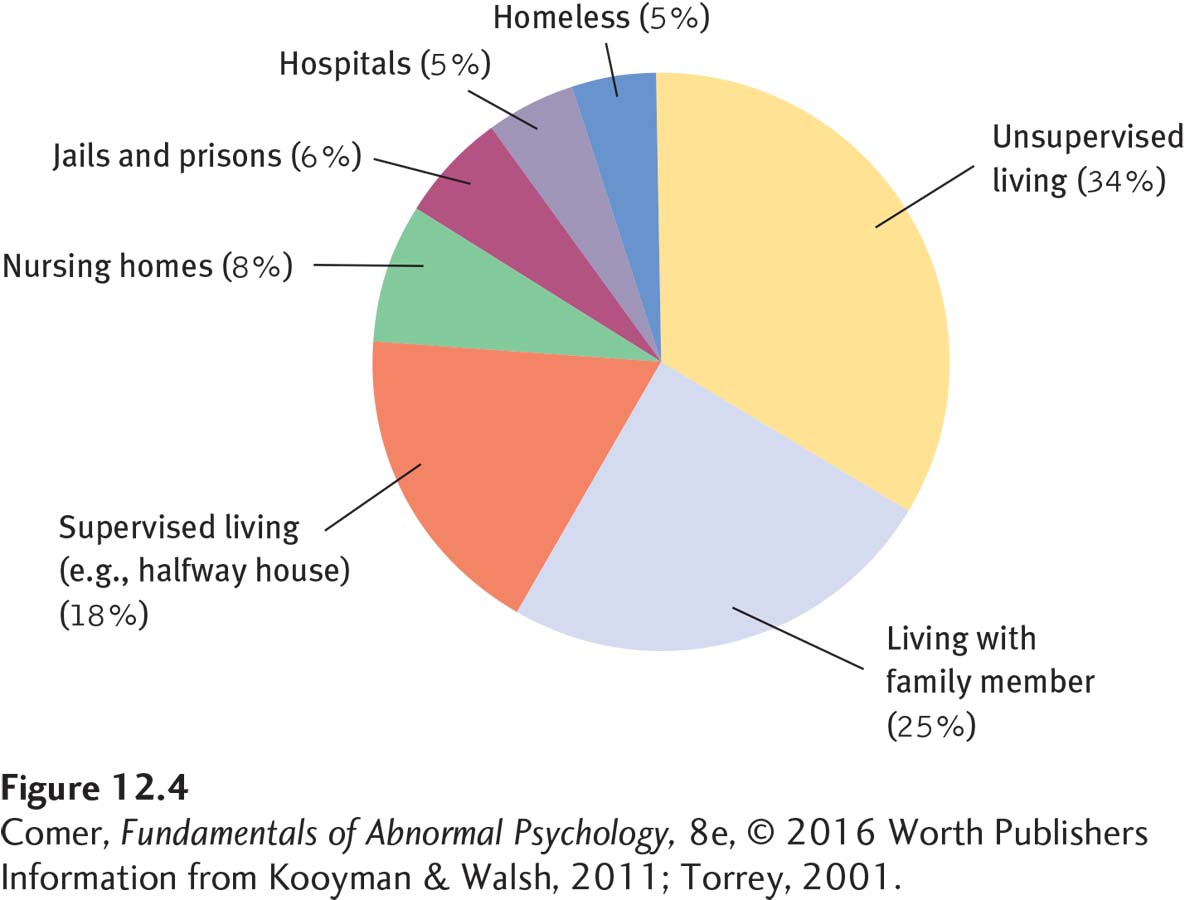

What Are the Consequences of Inadequate Community Treatment? What happens to people with schizophrenia and other severe disorders whose communities do not provide the services they need and whose families cannot afford private treatment (see Figure 12.4)? As you have read, a large number receive no treatment at all; many others spend a short time in a state hospital or semihospital and are then discharged prematurely, often without adequate follow-

Many of the people with severe mental disorders return to their families and receive medication and perhaps emotional and financial support, but little else in the way of treatment (Barrowclough & Lobban, 2008). Around 8 percent enter an alternative institution such as a nursing home or rest home, where they receive only custodial care and medication (Torrey, 2001). As many as 18 percent are placed in privately run residences where supervision often is provided by untrained staff—

Finally, a great number of people with schizophrenia and other severe disorders have become homeless (Ogden, 2014; Kooyman & Walsh, 2011). There are between 400,000 and 800,000 homeless people in the United States, and approximately one-

MediaSpeak

“Alternative” Mental Health Care

By Merrill Balassone, Washington Post, December 6, 2010

A n 18-

A woman lets out a long guttural scream to nobody in particular to turn off the lights.

A 24-

This is not the inside of a psychiatric hospital. It’s the B-

Stanislaus County is not unique. Experts say U.S. prisons and jails have become the country’s largest mental health institutions, its new asylums. Nearly four times more Californians with serious mental illnesses are housed in jails and prisons than in hospitals…. Nationally, 16 to 20 percent of prisoners are mentally ill, said Harry K. Wexler, a psychologist specializing in crime and substance abuse.

“I think it’s a national tragedy,” Wexler said. “Prisons are the institutions of last resort. The mentally ill are generally socially undesirable, less employable, more likely to be homeless and get on that slippery slope of repeated involvement in the criminal justice system.”

Those who staff prisons and jails are understandably ill-

Mentally ill offenders have higher recidivism rates than other inmates (they’re called “frequent fliers” in the criminal justice world) because they receive little psychiatric care after their release…. Wexler said these inmates also are more likely to commit suicide. Because they’re less capable of conforming to the rigid rules of a jailhouse, they can end up in isolation as punishment, Wexler said.

At 4:30 A.M. in the ….ail—

One nationally recognized solution is called a mental health treatment court, which gives offenders the choice between going to jail or following a treatment plan—

“We deal every day with this crisis of the mentally ill—

December 6, 2010, “Jails, Prisons Increasingly Taking Care of Mentally Ill” by Merrill Balassone. From The Modesto Bee, 12/6/2010, © 2010 McClatchy. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the copyright laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this content without express written permission is prohibited.

The Promise of Community Treatment Despite these very serious problems, proper community care has shown great potential for assisting people in recovering from schizophrenia and other severe disorders, and clinicians and many government officials continue to press to make it more available. In addition, a number of national interest groups have formed in countries around the world that push for better community treatment. In the United States, for example, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) began in 1979 with 300 members and has expanded to 200,000 members in more than 1,000 chapters (NAMI, 2014). Made up largely of families and people affected by severe mental disorders, NAMI has become not only a source of information, support, and guidance for its members but also a powerful lobbying force in state and national legislatures, and it has pressured community mental health centers to treat more people with schizophrenia and other severe disorders.

Today, community care is a major feature of treatment for people recovering from severe mental disorders in countries around the world. Both in the United States and abroad, well-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Schizophrenia and Jail

There are more people with schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders in jails and prisons than there are in all hospitals and other treatment facilities.

Chicago’s Cook County Jail, where several thousand of the inmates require daily mental health services, is now in effect the largest mental institution in the United States.

(Pruchno, 2014; Balassone, 2011; Steadman et al., 2009; Morrissey & Cuddeback, 2008; Peters et al., 2008)

Summing Up

HOW ARE SCHIZOPHRENIA AND OTHER SEVERE MENTAL DISORDERS TREATED? For more than half of the twentieth century, the main treatment for schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders was institutionalization and custodial care. In the 1950s, two in-

The discovery of antipsychotic drugs in the 1950s revolutionized the treatment of schizophrenia and other disorders marked by psychosis. Today they are almost always a part of treatment. Theorists believe that conventional antipsychotic drugs operate by reducing excessive dopamine activity in the brain. These drugs reduce the positive symptoms of schizophrenia more completely, or more quickly, than the negative symptoms.

The conventional antipsychotic drugs can also produce dramatic unwanted effects, particularly movement abnormalities. One such effect, tardive dyskinesia, apparently occurs in more than 10 percent of the people who take conventional antipsychotic drugs for an extended time and can be difficult or impossible to eliminate. In recent decades, atypical antipsychotic drugs have been developed; these seem to be more effective than the conventional drugs and to cause fewer or no extrapyramidal effects.

Today psychotherapy is often employed successfully in combination with antipsychotic drugs. Helpful forms include cognitive-

A community approach to the treatment of schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders began in the 1960s, when a policy of deinstitutionalization in the United States brought about a mass exodus of hundreds of thousands of patients from state institutions into the community. Among the key elements of effective community care programs are coordination of patient services by a community mental health center, short-