13.3 “Anxious” Personality Disorders

The cluster of “anxious” personality disorders includes the avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-

Avoidant Personality Disorder

avoidant personality disorder A personality disorder characterized by consistent discomfort and restraint in social situations, overwhelming feelings of inadequacy, and extreme sensitivity to negative evaluation.

People with avoidant personality disorder are very uncomfortable and inhibited in social situations, overwhelmed by feelings of inadequacy, and extremely sensitive to negative evaluation (APA, 2013). They are so fearful of being rejected that they give no one an opportunity to reject them—

Perhaps what made Malcolm pursue counseling was the painful awareness of his inability to socialize at a party hosted by a professor. A first-

When asked about personal relationships he had previously enjoyed, Malcolm admitted that any interaction was a source of frustration and worry. From the moment he left home for undergraduate school, he lived alone, attended functions alone, and found it nearly impossible to make conversation with anyone…. The expectancy that people would be rejecting ….recipitated profound gloom…. Despite a longing to relate and be accepted, Malcolm ….aintained a safe distance from all emotional involvement. [He] became remote from others and from needed sources of support. He ….ad learned to be watchful, on guard against ridicule, and ever alert ….o the most minute traces of annoyance expressed by others.

(Millon, 2011)

BETWEEN THE LINES

Feelings of Shyness

Around 48 percent of people in the United States consider themselves to be shy to some degree.

(Carducci, 2000)

People like Malcolm actively avoid occasions for social contact. At the center of this withdrawal lies not so much poor social skills as a dread of criticism, disapproval, or rejection. They are timid and hesitant in social situations, afraid of saying something foolish or of embarrassing themselves by blushing or acting nervous. Even in intimate relationships they express themselves very carefully, afraid of being shamed or ridiculed.

People with this disorder believe themselves to be unappealing or inferior to others. They exaggerate the potential difficulties of new situations, so they seldom take risks or try out new activities. They usually have few or no close friends, though they actually yearn for intimate relationships, and frequently feel depressed and lonely. As a substitute, some develop an inner world of fantasy and imagination (Millon, 2011).

Avoidant personality disorder is similar to social anxiety disorder (see Chapter 4), and many people with one of these disorders also experience the other (Eikenaes et al., 2015, 2013). The similarities include a fear of humiliation and low confidence. Some theorists believe that there is a key difference between the two disorders—

Around 2.4 percent of adults have avoidant personality disorder, men as frequently as women (APA, 2013; Sansone & Sansone, 2011). Many children and teenagers are also painfully shy and avoid other people, but this is usually just a normal part of their development.

How Do Theorists Explain Avoidant Personality Disorder? Theorists often assume that avoidant personality disorder has the same causes as anxiety disorders—

BETWEEN THE LINES

Shyness and the Arts

In recent years, the music industry has been strongly influenced by stars with extremely shy, reticent demeanors.

The alternative rock band My Bloody Valentine often plays with their backs to the audience and spearheaded an influential pop movement called “shoegaze” based on their tendency to look away or at the floor during shows.

In early shows, indie rock musician Sufjan Stevens would nervously applaud his audience when they clapped for him.

For many of her initial concerts, folk singer Cat Power (Chan Marshall) would not look at the audience and would weep or run offstage during shows.

Meg White, drummer for the two-

piece rock band White Stripes, appeared uncomfortable and quiet both onstage and during rarely given interviews. The group disbanded after “acute anxiety” forced her to cancel a 2007 tour. Grammy-

award winning singer Adele has revealed, “I’m scared of audiences. One show …. was so nervous, I escaped out the fire escape.”

Psychodynamic theorists focus mainly on the general sense of shame that people with avoidant personality disorder feel (Svartberg & McCullough, 2010). Some trace the shame to childhood experiences such as early bowel and bladder accidents. If parents repeatedly punish or ridicule a child for having such accidents, the child may develop a negative self-

Similarly, cognitive theorists believe that harsh criticism and rejection in early childhood may lead certain people to assume that others in their environment will always judge them negatively. These people come to expect rejection, misinterpret the reactions of others to fit that expectation, discount positive feedback, and generally fear social involvements—

Behavioral theorists suggest that people with avoidant personality disorder typically fail to develop normal social skills, a failure that helps maintain the disorder. In support of this position, several studies have found social skills deficits among people with avoidant personality disorder (Kantor, 2010; Herbert, 2007). Most behaviorists agree, however, that these deficits first develop as a result of the individuals avoiding so many social situations.

Treatments for Avoidant Personality Disorder People with avoidant personality disorder come to therapy in the hope of finding acceptance and affection. Keeping them in treatment can be a challenge, however, for many of them soon begin to avoid the sessions. Often they distrust the therapist’s sincerity and start to fear his or her rejection. Thus, as with several of the other personality disorders, a key task of the therapist is to gain the person’s trust (Colli et al., 2014; Leichsenring & Salzer, 2014).

Beyond building trust, therapists tend to treat people with avoidant personality disorder much as they treat people with social anxiety disorder and other anxiety disorders. Such approaches have had at least modest success (Kantor, 2010; Porcerelli et al., 2007). Psychodynamic therapists try to help clients recognize and resolve the unconscious conflicts that may be operating (Leichsenring & Salzer, 2014). Cognitive therapists help them change their distressing beliefs and thoughts and improve their self-

Dependent Personality Disorder

dependent personality disorder A personality disorder characterized by a pattern of clinging and obedience, fear of separation, and an ongoing need to be taken care of.

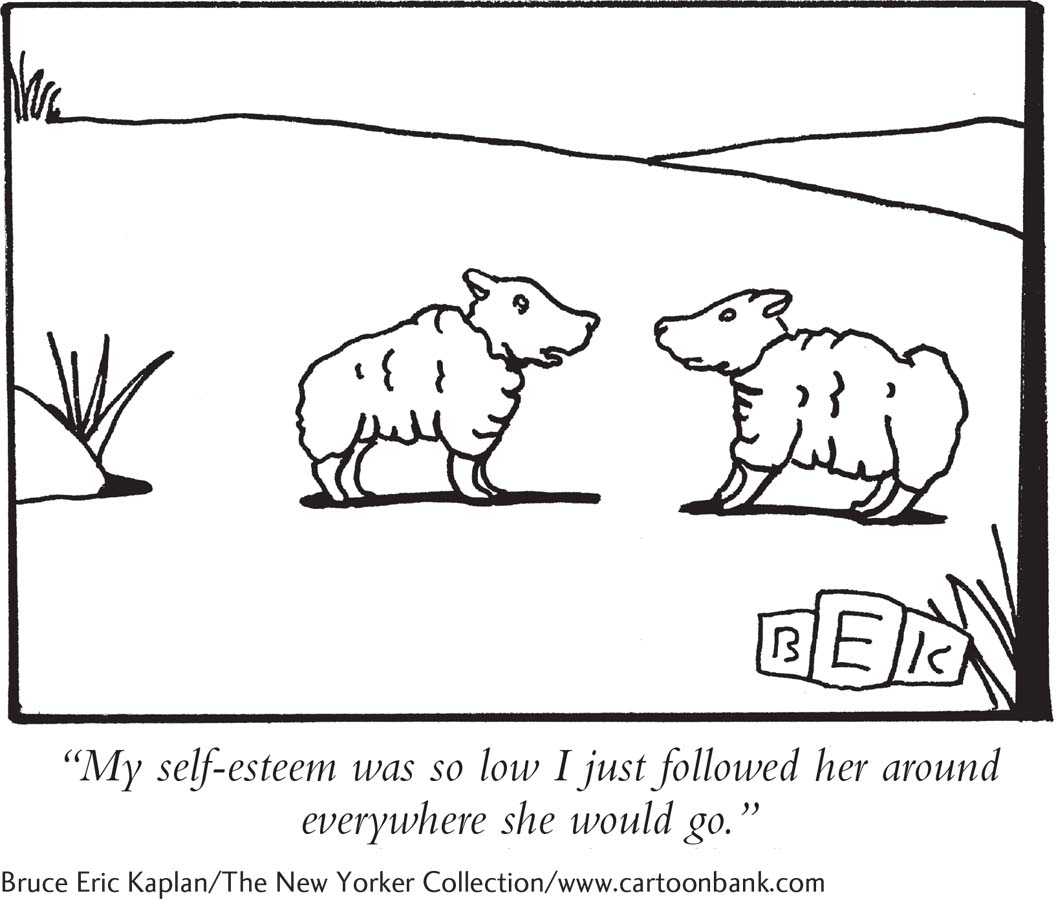

People with dependent personality disorder have a pervasive, excessive need to be taken care of (APA, 2013). As a result, they are clinging and obedient, fearing separation from their parent, spouse, or other person with whom they are in a close relationship. They rely on others so much that they cannot make the smallest decision for themselves. Matthew is a case in point.

Matthew is a 34-

Matthew works at a job several grades below what his education and talent would permit. On several occasions he has turned down promotions because he didn’t want the responsibility of having to supervise other people or make independent decisions. He has worked for the same boss for 10 years ….nd is ….ighly regarded as a dependable and unobtrusive worker. He has two very close friends whom he has had since early childhood. He has lunch with one of them every single workday and feels lost if his friend is sick and misses a day.

Matthew is the youngest of four children…. He had considerable separation anxiety as a child ….ifficulty falling asleep unless his mother stayed in the room ….nd unbearable homesickness when he occasionally tried “sleepovers.” As a child he was teased by other boys because of his lack of assertiveness and was often called a baby. He has lived at home his whole life except for 1 year of college, from which he returned because of homesickness.

(Spitzer et al., 1994, pp. 179–

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“The deepest principle of human nature is the craving to be appreciated.”

William James

It is normal and healthy to depend on others, but those with dependent personality disorder constantly need assistance with even the simplest matters and have extreme feelings of inadequacy and helplessness. Afraid that they cannot care for themselves, they cling desperately to friends or relatives.

As you just observed, people with avoidant personality disorder have difficulty initiating relationships. In contrast, people with dependent personality disorder have difficulty with separation. They feel completely helpless and devastated when a close relationship ends, and they quickly seek out another relationship to fill the void. Many cling persistently to relationships with partners who physically or psychologically abuse them (Loas et al., 2015, 2011).

Lacking confidence in their own ability and judgment, people with this disorder seldom disagree with others and allow even important decisions to be made for them (Millon, 2011). They may depend on a parent or spouse to decide where to live, what job to have, and which neighbors to befriend. Because they so fear rejection, they are overly sensitive to disapproval and keep trying to meet other people’s wishes and expectations, even if it means volunteering for unpleasant or demeaning tasks.

Many people with dependent personality disorder feel distressed, lonely, and sad; often they dislike themselves. Thus they are at risk for depressive, anxiety, and eating disorders (Bornstein, 2012, 2007). Their fear of separation and their feelings of helplessness may leave them particularly prone to suicidal thoughts, especially when they believe that a current relationship is about to end (Bornstein, 2012; Kiev, 1989).

Surveys suggest that fewer than 1 percent of the population experience dependent personality disorder (APA, 2013; Sansone & Sansone, 2011). For years, clinicians have believed that more women than men display this pattern, but some research suggests that the disorder is just as common in men (APA, 2013).

How Do Theorists Explain Dependent Personality Disorder? Psychodynamic explanations for dependent personality disorder are very similar to those for depression (Svartberg & McCullough, 2010). Freudian theorists argue, for example, that unresolved conflicts during the oral stage of development can give rise to a lifelong need for nurturance, thus heightening the likelihood of a dependent personality disorder (Bornstein, 2012, 2007, 2005). Similarly, object relations theorists say that early parental loss or rejection may prevent normal experiences of attachment and separation, leaving some children with fears of abandonment that persist throughout their lives (Caligor & Clarkin, 2010). Still other psychodynamic theorists suggest that, to the contrary, many parents of people with this disorder were overinvolved and overprotective, thus increasing their children’s dependency, insecurity, and separation anxiety (Sperry, 2003).

Behaviorists propose that parents of people with dependent personality disorder unintentionally rewarded their children’s clinging and “loyal” behavior, while at the same time punishing acts of independence, perhaps through the withdrawal of love. Alternatively, some parents’ own dependent behaviors may have served as models for their children (Bornstein, 2012, 2007).

Cognitive theorists identify two maladaptive attitudes as helping to produce and maintain this disorder: (1) “I am inadequate and helpless to deal with the world,” and (2) “I must find a person to provide protection so I can cope.” Dichotomous (black-

Treatments for Dependent Personality Disorder In therapy, people with dependent personality disorder usually place all responsibility for their treatment and well-

Treatment for dependent personality disorder can be at least modestly helpful. Psychodynamic therapy for this pattern focuses on many of the same issues as therapy for depressed people, including the transference of dependency needs onto the therapist (Svartberg & McCullough, 2010). Cognitive-

As with avoidant personality disorder, a group therapy format can be helpful because it provides opportunities for the client to receive support from a number of peers rather than from a single dominant person (Perry, 2005; Sperry, 2003). In addition, group members may serve as models for one another as they practice better ways to express feelings and solve problems.

Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder

obsessive-

People with obsessive-

Joseph was advised to seek assistance from a therapist following several months of relatively sleepless nights and a growing immobility and indecisiveness at his job. When first seen, he reported feelings of extreme self-

The precipitant for this sudden increase in discomfort was a forthcoming change in his academic post. New administrative officers had assumed authority at the college, and he was asked to resign his deanship to return to regular departmental instruction. In the early sessions, Joseph spoke largely of his fear of facing classroom students again, wondered if he could organize his material well, and doubted that he could keep classes disciplined and interested in his lectures. It was his preoccupation with these matters that he believed was preventing him from concentrating and completing his present responsibilities.

At no time did Joseph express anger toward the new college officials for the demotion he was asked to accept; he repeatedly voiced his “complete confidence” in the “rationality of their decision.” Yet, when face-

Joseph was the second of two sons, younger than his brother by three years. His father was a successful engineer, and his mother a high school teacher. Both were “efficient, orderly, and strict” parents. Life at home was “extremely well planned,” with “daily and weekly schedules of responsibility posted” and “vacations arranged a year or two in advance.” Nothing apparently was left to chance…. Joseph adopted the “good boy” image. Unable to challenge his brother either physically, intellectually, or socially, he became a “paragon of virtue.” By being punctilious, scrupulous, methodical, and orderly, he could avoid antagonizing his perfectionistic parents, and would, at times, obtain preferred treatment from them. He obeyed their advice, took their guidance as gospel, and hesitated making any decision before gaining their approval. Although he recalled “fighting” with his brother before he was 6 or 7, he “restrained my anger from that time on and never upset my parents again.”

(Millon, 2011, 1969, pp. 278–

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“I don’t care about the rules. In fact, if I don’t break the rules at least 10 times in every song then I’m not doing my job properly.”

Jeff Beck, guitarist

In Joseph’s concern with rules and order and doing things right, he has trouble seeing the larger picture. When faced with a task, he and others who have obsessive-

People with this personality disorder set unreasonably high standards for themselves and others. Their behaviors extend well beyond the realm of conscientiousness. They can never be satisfied with their performance, but they typically refuse to seek help or to work with a team, convinced that others are too careless or incompetent to do the job right. Because they are so afraid of making mistakes, they may be reluctant to make decisions.

They also tend to be rigid and stubborn, particularly in their morals, ethics, and values. They live by a strict personal code and use it as a yardstick for measuring others. They may have trouble expressing much affection, and their relationships are sometimes stiff and superficial (Cain et al., 2015). In addition, they are often stingy with their time or money. Some cannot even throw away objects that are worn out or useless (APA, 2013).

According to surveys, as many as 7.9 percent of the adult population display obsessive-

Many clinicians believe that obsessive-

How Do Theorists Explain Obsessive-

Freudian theorists suggest that people with obsessive-

Cognitive theorists have little to say about the origins of obsessive-

Treatments for Obsessive-

BETWEEN THE LINES

A Critical Difference

People with obsessive-

People with obsessive-

Summing Up

“ANXIOUS” PERSONALITY DISORDERS Three of the personality disorders in DSM-