When the Fed Does Too Much

The Fed has considerable power to influence aggregate demand but, as we argued earlier, that power is constrained by uncertainty and by an inability for anyone to fully understand the complexity of the economy. As a result, it’s possible for the Federal Reserve to make booms and recessions worse rather than better. For example, a number of economists have argued that Federal Reserve policy in 2001–2004 contributed to the housing boom and eventual bust that led to the financial crisis in 2007–2008. Of course, many factors contributed to the financial crisis, including too much leverage and irrational exuberance, as discussed in Chapter 29 and Chapter 23. The financial crisis and the Fed’s role in it are highly debated topics among economists and a consensus has not yet been reached. Nevertheless, to see how the Fed might have contributed to the financial crisis, let’s go back to the late 1990s and the recession of 2001.

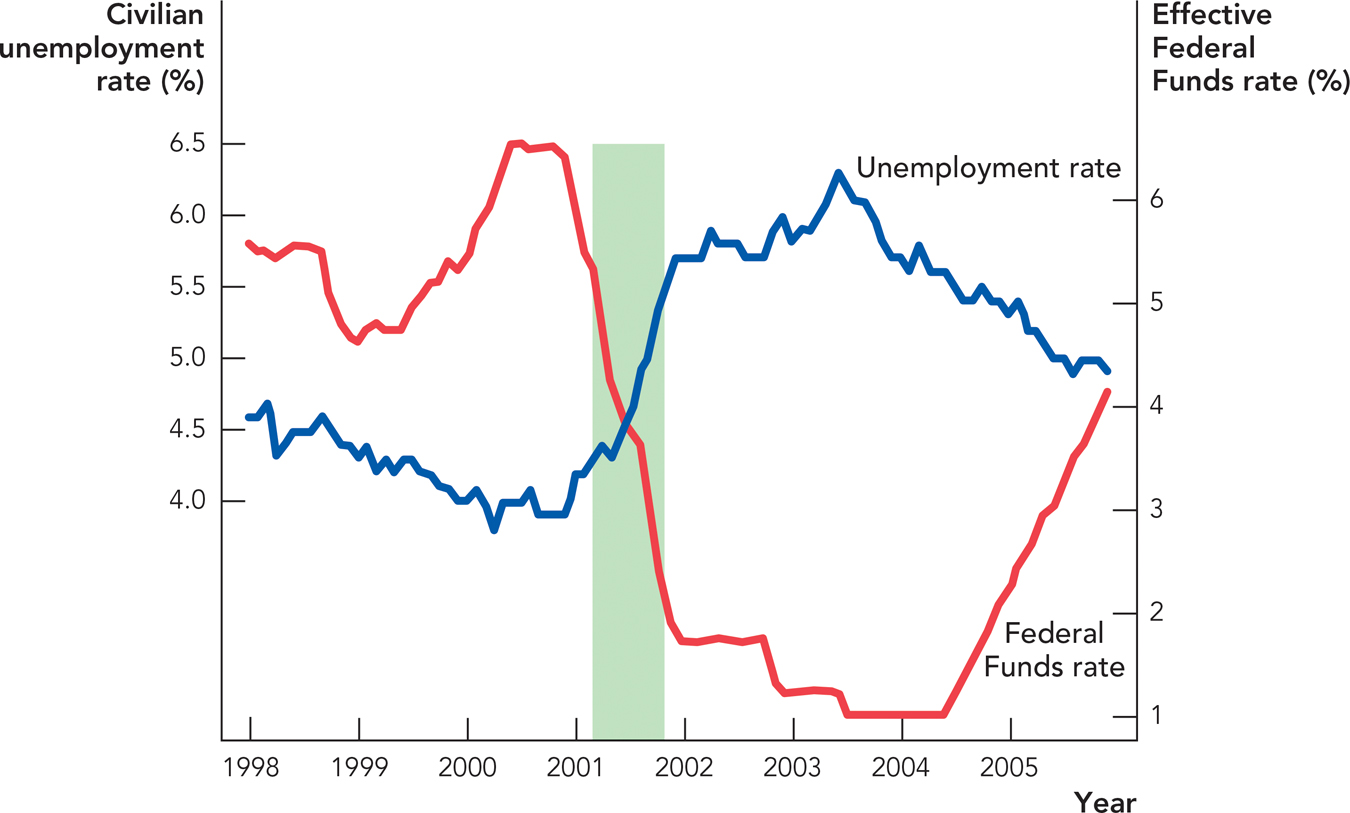

In the late 1990s, the American economy was the envy of the world. Economic growth was strong and the unemployment rate was low, even dipping below 4% in 2000. The recession that began in early 2001 didn’t last long but there were troubling signs that not all was well. In particular, notice from Figure 35.5 that the unemployment rate continued to increase even after the recession had officially ended.* From a rate of 4% in 2000, unemployment increased during the recession to 5.5% and then kept increasing until it peaked at 6.3% (almost a 50% increase) in June 2003. In fact, even three years after the recession ended, the unemployment rate remained near its recession high.

FIGURE 35.5

The Federal Reserve was very concerned about the unemployment rate and it also worried about the psychological blow to consumer confidence after the terrorist attacks on 9/11. To combat the high unemployment rate, the Fed tried to increase aggregate demand through expansionary monetary policy. Figure 35.5 shows one measure of the Fed’s efforts, the Federal Funds rate. As described in Chapter 34, the Federal Funds rate is a short-term interest rate that is largely under the control of the Federal Reserve. During the recession, the Fed pushed down the Federal Funds rate from about 6.5% in 2000 to 2% at the end of 2001 when the recession ended. But even after the recession ended, the Fed pushed the Federal Funds rate even lower to below 2%. Indeed, from mid-2003 to mid-2004, the Fed held the Federal Funds rate at 1%, an extraordinarily low rate.

The low Federal Funds rate helped to make credit cheap throughout the economy. This meant it was relatively easy to borrow money and it encouraged people to take out more mortgages, bidding up the price of homes. Unfortunately, easy credit can start or intensify a bubble.

The concept of a speculative bubble was introduced in Chapter 29, but to restate the fundamental idea here, a bubble arises when asset prices rise far higher, and more rapidly, than can be accounted for by the fundamental prospects of the asset. Investors get carried away by the prospect for gain and they underestimate the prospect of loss. Prices are instead driven by shifts in market psychology and successive waves of irrational exuberance.

Now imagine an investor who is thinking of buying a bunch of homes, not to live in them, but rather to resell them quickly for a profit (known as “flipping”). Cheap, easy credit makes it easier for investors of this kind to operate and thus it can intensify bubbles. The low interest rates are, in essence, signaling to market participants that credit is easy and it is a good idea to borrow money. In the words of the Austrian economists Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich A. Hayek, these are distorted price signals. A distorted price signal arises when government policy, or in this particular case the Fed’s monetary policy, moves a price in a manner that encourages investors to take risks. Of course, the investors didn’t have to take foolish risks. If you stockpile bananas on your roof and the roof caves in, it’s your mistake even if the government subsidized the purchase of bananas. Nevertheless, cheap bananas and cheap credit probably make these mistakes more likely. The mistakes here were not exclusive to the Fed: The government-sponsored mortgage agencies, called Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, guaranteed and subsidized a lot of low-quality mortgages, as did the private insurance firm AIG, and that also made the housing bubble worse.

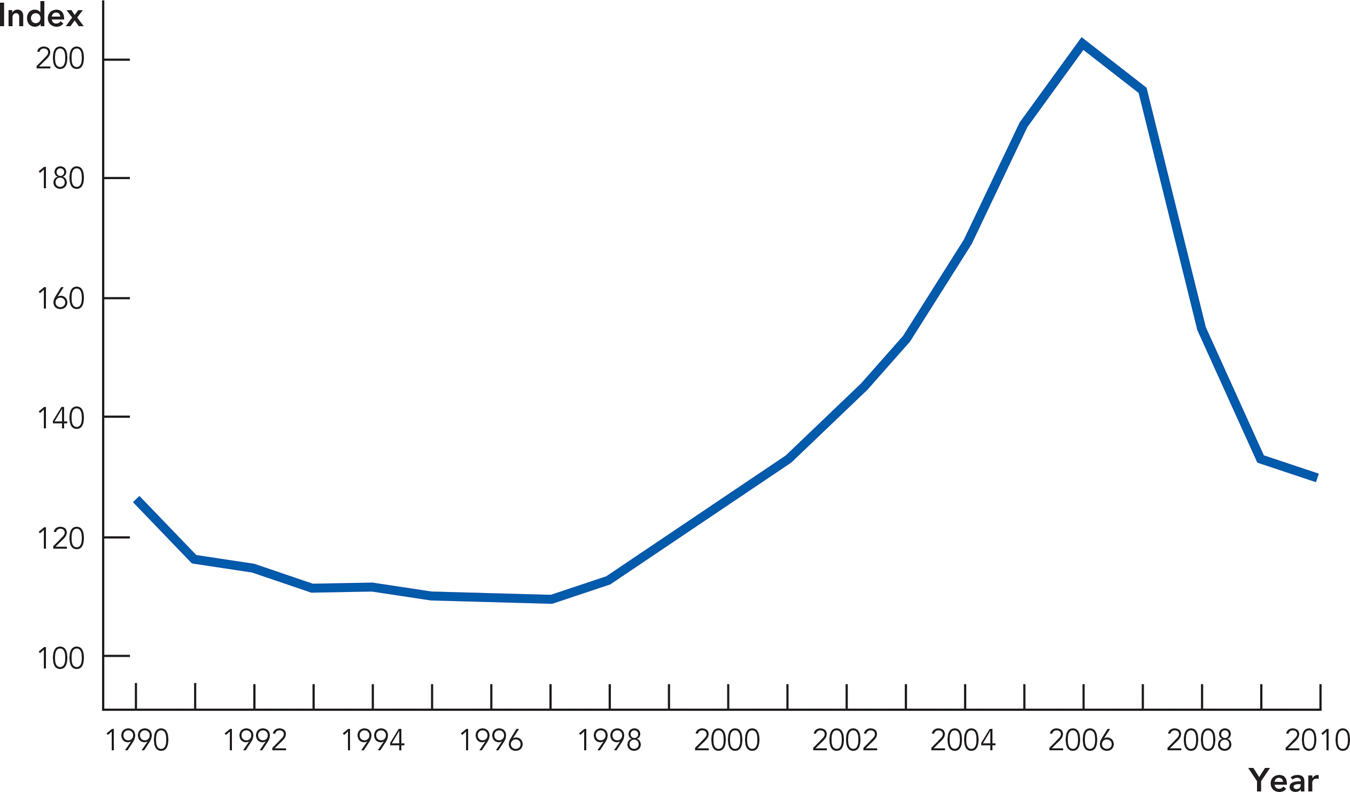

The Fed began to raise interest rates in mid-2004 but rates remained very low until at least mid-2005. In 2006 housing prices peaked, and by 2007 were in free fall. Figure 35.6 illustrates what happened.

FIGURE 35.6

The problem for the economy, of course, came when the price of real estate started to fall in 2006. New home construction dropped very quickly. Homeowners felt poorer and started to spend less, reducing aggregate demand. In addition, the real estate crash contributed to a freezing up of financial intermediation as banks and other intermediaries took huge losses on poor investments in mortgage securities (as discussed in Chapter 29). Since bank lending is a main generator of M1 and M2, this means lower rates of growth for the money supply. As a result, economic growth rates started to decline. By the fall of 2008, the growth rate was negative, meaning that the American economy was shrinking.

Dealing with Asset Price Bubbles

The Fed probably made a mistake holding the Federal Funds so low for so long. But more generally, how should the Fed respond to asset price increases? It’s easy to say in retrospect that the Fed should have raised rates sooner or should have raised rates more quickly in response to the housing bubble, but there are several problems with this line of thinking. First, few people expected that a fall in housing prices would wreak as much havoc as it did on financial intermediaries and the general economy. The economy, for example, had quickly recovered from the much larger drop in stock prices during the tech bubble that ended with the recession of 2001. The Fed may have believed that trying to reduce unemployment was worth the risk of generating a bubble in asset prices.

Second, it’s not always easy to identify when a bubble is present, for reasons discussed in Chapter 29. If everyone knew it was an unsustainable bubble, then all should have invested accordingly and bet against the bubble, thereby enriching themselves and also stopping the bubble in the first place. Of course, that isn’t what happened and the bursting of the bubble was in large part a surprise to many people, including the Fed. Also, don’t make the mistake of thinking that if prices rise a lot and then fall, that must mean a bubble was present. Prices can rise and fall for reasons closely related to fundamentals and still cause macroeconomic problems.

Third, monetary policy is a crude means of “popping” a bubble. Monetary policy can influence aggregate demand, or target credit markets at the aggregate level, but monetary policy can’t push the demand for housing down and keep the demand for everything else up. Thus, popping a bubble means reducing the growth rate of GDP for the broader economy as a whole. Is it worth the price, especially when we do not always know when we have an unsustainable bubble on our hands?

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 35.4

How can the Fed tell when increases in asset prices reach the bubble stage?

How can the Fed tell when increases in asset prices reach the bubble stage?

Question 35.5

If the Fed thinks there is a bubble in housing prices and contracts the growth in the money supply to pop it, what collateral damage can it cause?

If the Fed thinks there is a bubble in housing prices and contracts the growth in the money supply to pop it, what collateral damage can it cause?

Note, however, that in addition to monetary policy, the Fed does have the power to regulate banks and it probably could have restrained some of the “subprime,” no-questions-asked mortgages that were sold during the boom and later went into default. That would have been the best way of limiting the bubble without taking down the broader economy.

Economists have not settled on what to do when asset prices like housing prices or stock prices boom. The bottom line is this: Monetary policy is difficult in the worst of times and it’s not easy in the best of times.

Rules vs. Discretion

The possibility of the “Too little” and “Too much” responses, or in other words the imperfections of monetary policy, has led to a debate over rules vs. discretion when it comes to monetary policy. Ideally, monetary policy tries to adjust for shocks to aggregate demand, but it is often debated whether these adjustments are effective in reducing the volatility of output. If the Fed responds too often in the wrong direction or with the wrong strength, GDP volatility will increase rather than decrease.

Economists who think that the Fed is likely to make a lot of mistakes believe that apart from extreme cases, the Fed is best advised to follow a consistent policy and not try to adjust to every aggregate demand shock. A typical monetary rule would set target ranges for the monetary aggregates like Ml or M2 or for the rate of inflation. Nobel Prize winner Milton Friedman, for example, advocated a strict rule in which the money supply would grow by 3% a year every year, since the U.S. economy has a long-run growth rate near 3%.

A monetary rule, however, works best only when v, monetary velocity, doesn’t change rapidly. To see one problem with a monetary rule, let’s return to the quantity theory of money and the relationship

Mv = PY

where M is the money supply, v is velocity, P is the price index, and Y is real GDP.

A monetary rule says keep M constant (or growing at a constant rate) but that means that the Fed must ignore changes in v. In times of crisis such as the Great Depression or the Great Recession, we have seen that v can fall rapidly as consumers and businesses cut back on their spending and banks reduce lending. If M is constant and v falls, then either P must fall or Y must fall. Since prices are sticky, the usual outcome is that both P and Y fall, and a fall in Y means a recession.

To avoid some of the defects of a monetary rule but still constrain the Federal Reserve from too much discretion, other economists have suggested a nominal GDP rule. The nominal GDP rule is simple: it says keep Mv constant (or growing at a constant rate). If Mv doesn’t change or grows smoothly, then so does PY, and that would be ideal.

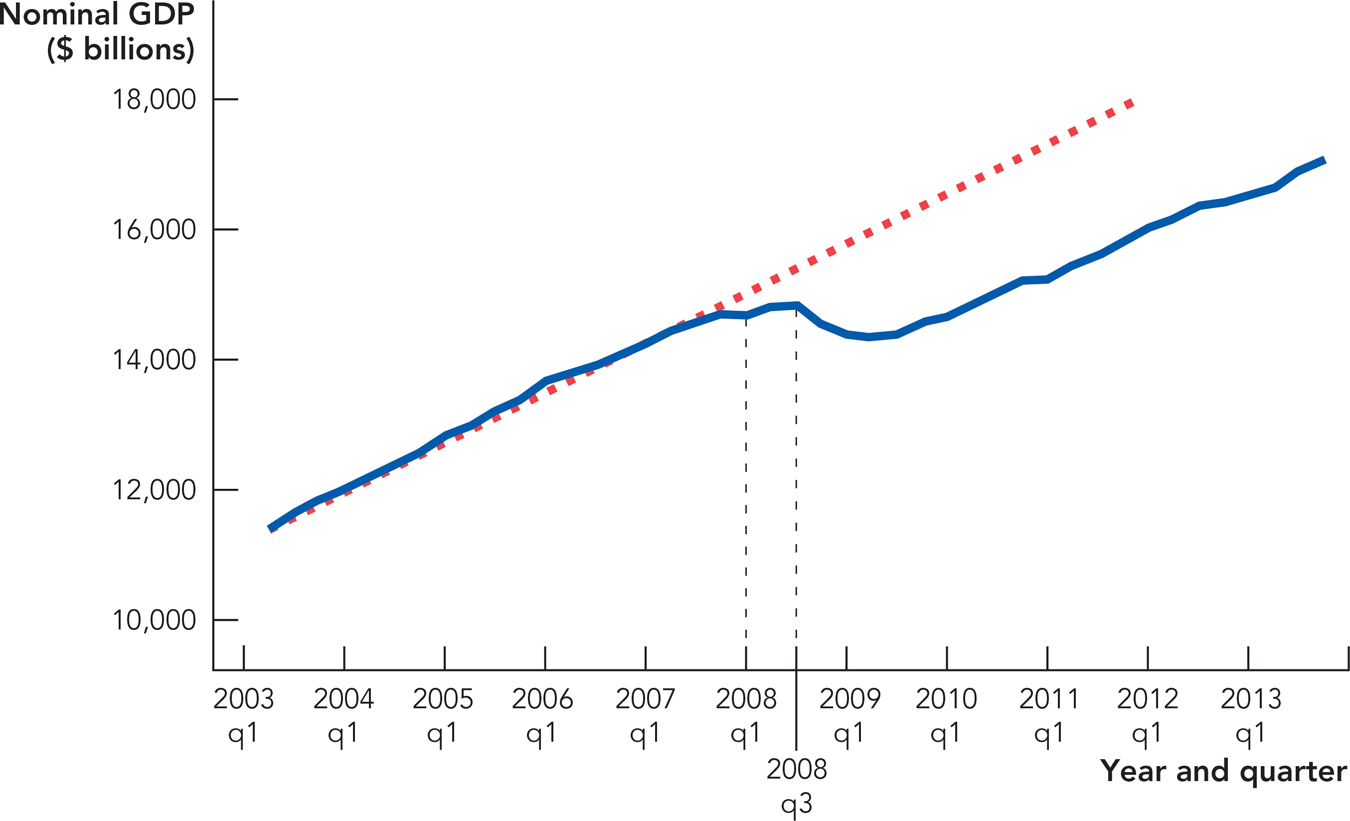

Figure 35.7 shows nominal GDP from 2003 to 2013. Before the recession, which began in December of 2007, nominal GDP had been increasing at a little over 5% a year. As the recession began, however, nominal GDP began to increase more slowly, and then in the third quarter of 2008 it started to plunge.

FIGURE 35.7

A nominal GDP rule would have required the Federal Reserve to increase M by as much as it takes to keep nominal GDP growing at around 5% a year (along the path given by the dotted red line). As you can see, the Fed did not follow a nominal GDP rule.

If the Fed had followed a nominal GDP rule, the recession of 2008 would have been much milder. But it’s not clear that the Fed could have followed a nominal GDP rule. To be fair, the Fed was not asleep at the wheel in 2008 and they did respond to the fall in nominal GDP by increasing the monetary base. Indeed, between August of 2008 and December of 2008, the monetary base doubled! That is by far the largest increase in the monetary base in the Fed’s entire history. Proponents of a nominal GDP rule say the Fed did too little, too late. In this view, if the Fed had acted sooner and given the markets clearer guidance, then v would have stayed higher and the Fed could have more easily returned nominal GDP to its trend.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 35.6

Why did Milton Friedman argue for a set rule of 3% money growth per year? Why not 2% or 0%?

Why did Milton Friedman argue for a set rule of 3% money growth per year? Why not 2% or 0%?

As emphasized earlier, much of what the Fed does is to try to manage market confidence and expectations. A rule such as a nominal GDP rule might help to stabilize expectations, especially in normal times. But if a rule suggests that the Fed must do things it has never done before, market participants may wonder whether the Fed will really follow the rule or even if it can follow the rule. It may be hard for the Fed to maintain a growth path for Mv when credit is collapsing, for instance. Moreover, if a rule suggests that the Fed should do something it has never done before, should and will the Fed follow the rule? It’s difficult to know the results of a rule when it requires the Fed to take actions that are outside historical experience.