Intertemporal Substitution

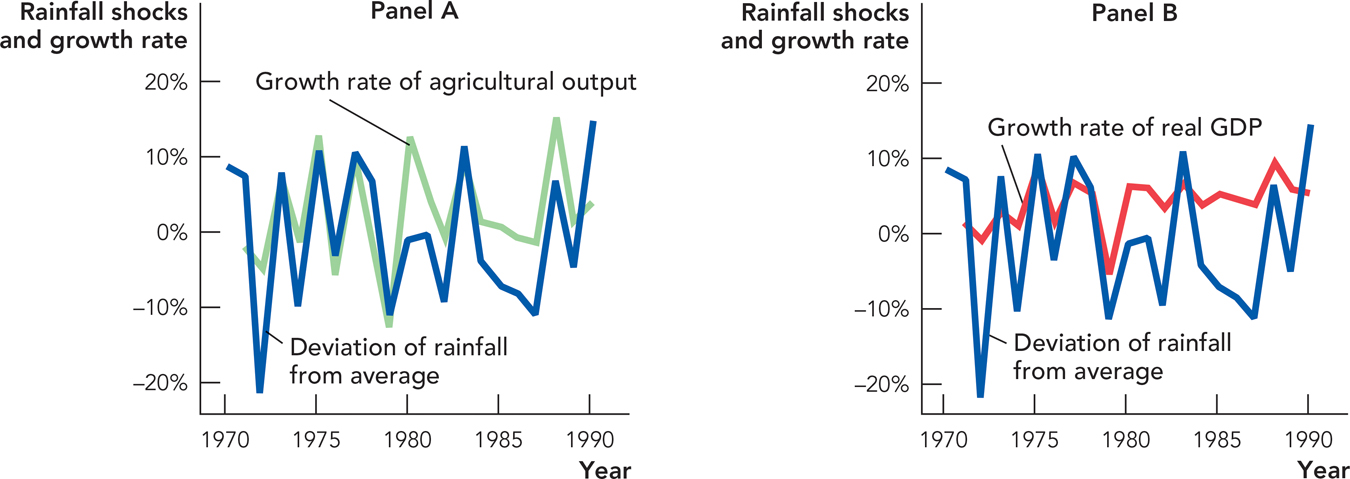

Let’s go back to our farm example from Chapter 13. We showed that when the weather fluctuates, so does output and therefore so does GDP, especially in agricultural economies such as India. Once again, Figure 14.1 below shows how rainfall shocks are correlated with the growth rate of agricultural output (Panel A) and GDP (Panel B) in India.

FIGURE 14.1

Source: Reserve Bank of India and Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology.

When rainfall is below average, the same capital and labor inputs produce less agricultural output—that is the direct effect of the negative rainfall shock. But the shock to GDP is caused not simply by less rainfall but also by how people respond to less rainfall. If rainfall is below average, for example, farmers may work less hard and devote less capital to their fields.

Why would farmers choose to use less labor and capital in response to a negative shock? Think about it this way: When the crops are bountiful, it makes sense to work from dawn till dusk because each hour of additional work pays a lot—remember the old saying, make hay when the sun shines? But when the crops are poor, the returns to an additional hour of work are low and so farmers may rationally decide to work less. The same is true for applications of capital. When planted crops will blossom, it may be worth paying the fuel costs to run the tractor an extra hour. When planted crops will in any case wither, why bother spending the money on fuel? Just leave the tractor in the shed.

Intertemporal substitution is the allocation of consumption, work, and leisure across time to maximize well-being.

Economists call this effect intertemporal substitution. The term means that a person or a business is most likely to work hard when working hard brings the greatest return. We work hard in some times and rest in others, and of course we pick and choose the spots when we try hardest. We are substituting effort across time and thus the expression intertemporal substitution.

When you study for a test, do you practice intertemporal substitution or do you study an equal amount every day? As a test approaches, you probably study harder, turning down some opportunities for fun. Once the test is over, you study less and have more fun. Intertemporal substitution means that when you study, you study a lot, and when you party, well, you know.

Intertemporal substitution, however, is not just about substituting between work and leisure. We pointed out in Chapter 1, for example, that when jobs are plentiful and wages are increasing, there is a tendency for fewer people to enter college, but when jobs are scarce and wages are stagnant, more people decide to invest in an education. Students understand that the opportunity cost of getting an education falls when jobs are scarce.

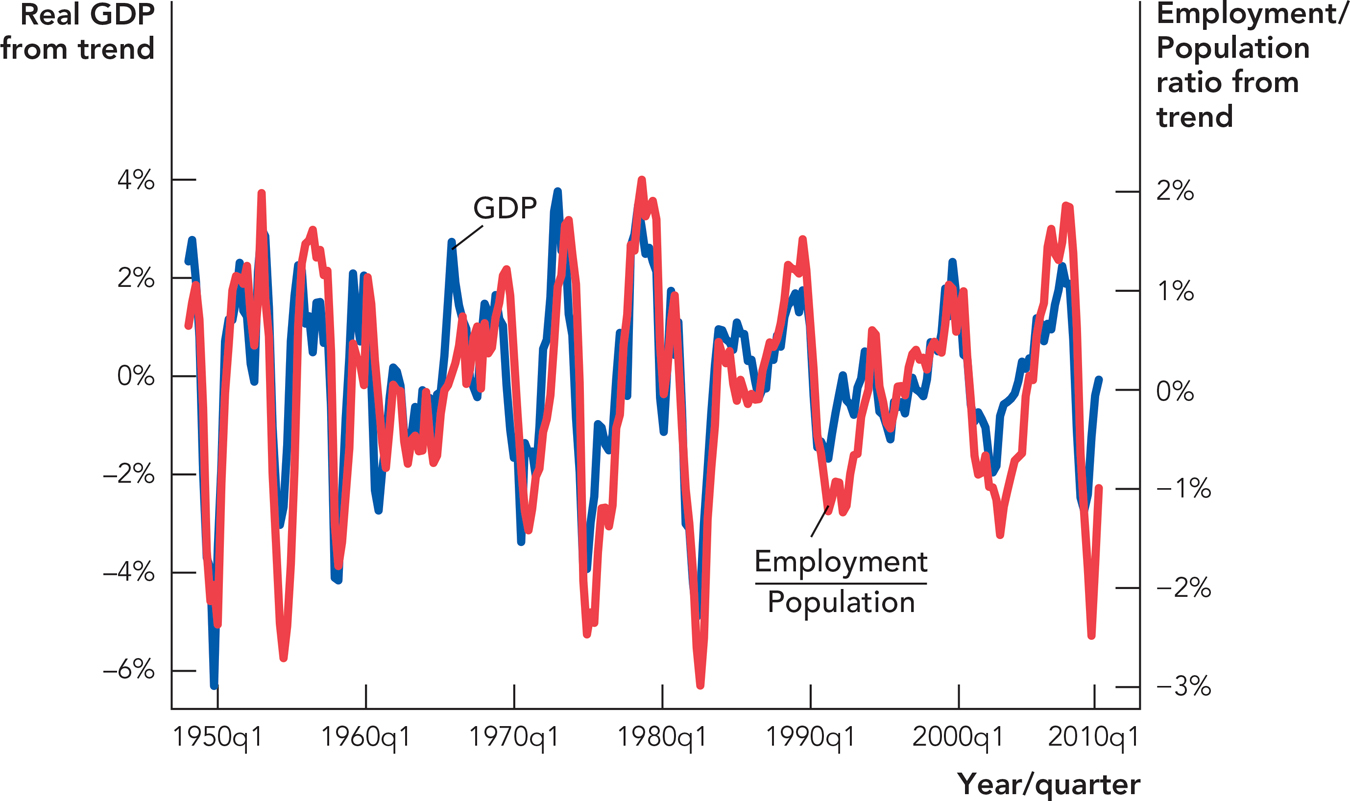

During a boom, people are less likely to retire or take early retirement—why not stay another year or two and bank the high wages? Similarly, homemakers and other people who might otherwise not work will choose to enter the workforce during boom periods. During recessions, people are more likely to take early retirement or focus on home making. Figure 14.2 shows that when GDP is growing faster than trend, the employment to population ratio also tends to grow faster than trend. The implication is that the supply of labor increases in a boom and falls during a recession.

FIGURE 14.2

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and Bureau of Economic Analysis.

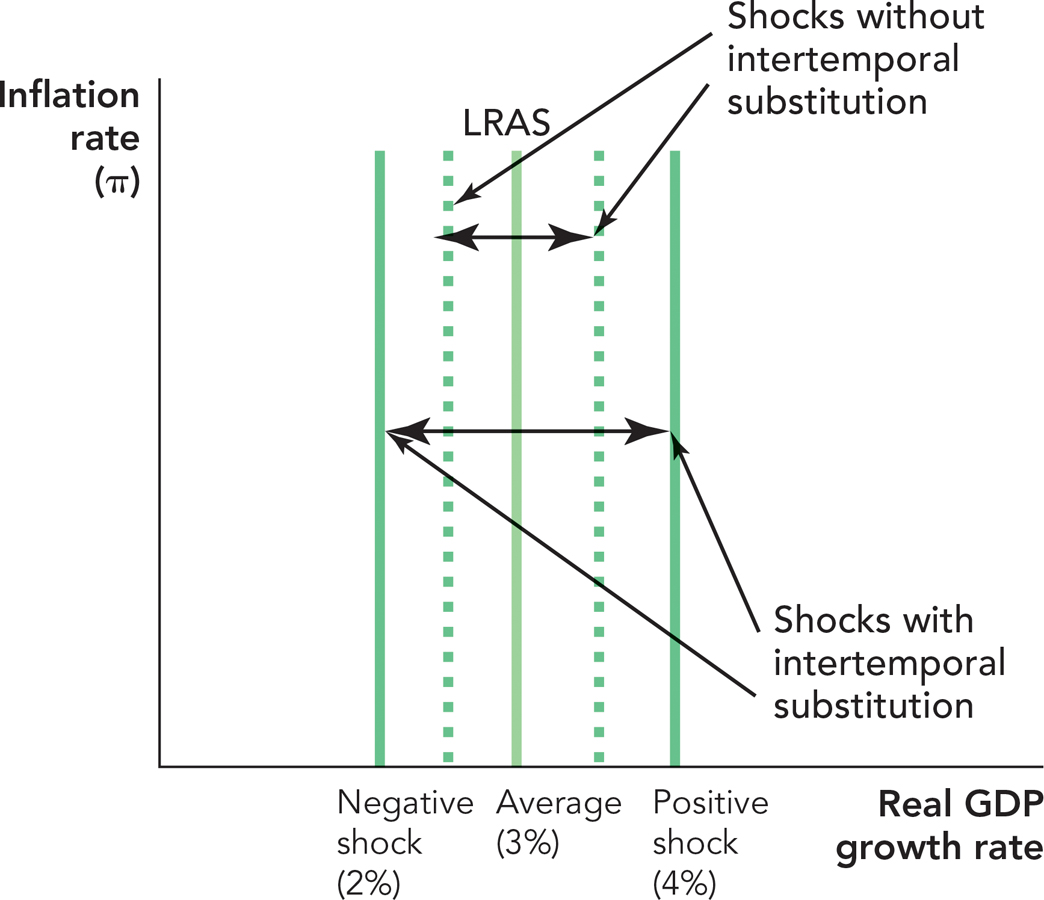

Notice that intertemporal substitution magnifies negative economic shocks. When things go a bit bad, the return to work and investing fall, and often people work less and invest less, which makes things go just a little worse. The ripple effects of this process help turn an initial shock into a broader recession. Of course, on the upside, intertemporal substitution can feed an economic boom and make it more intense. If things are going well, many people will be inclined to work harder, which will in turn increase output and make things go even better. Figure 14.3 shows how intertemporal substitution amplifies shocks to the long-run aggregate supply curve. Intertemporal substitution is hardly the only force behind employment decisions (see Chapter 11) but it does play a role in magnifying shocks, both on the upside and the downside.

FIGURE 14.3

Let’s turn to another transmission mechanism, uncertainty and irreversible investments.