So When Is Fiscal Policy a Good Idea?

The macroeconomic case for government spending is strongest when the government faces some immediate emergency, such as a war, a worsening depression, or a natural disaster. Government spending is best for the macroeconomy when it is worth incurring some long-run costs to get a short-run economic boost.

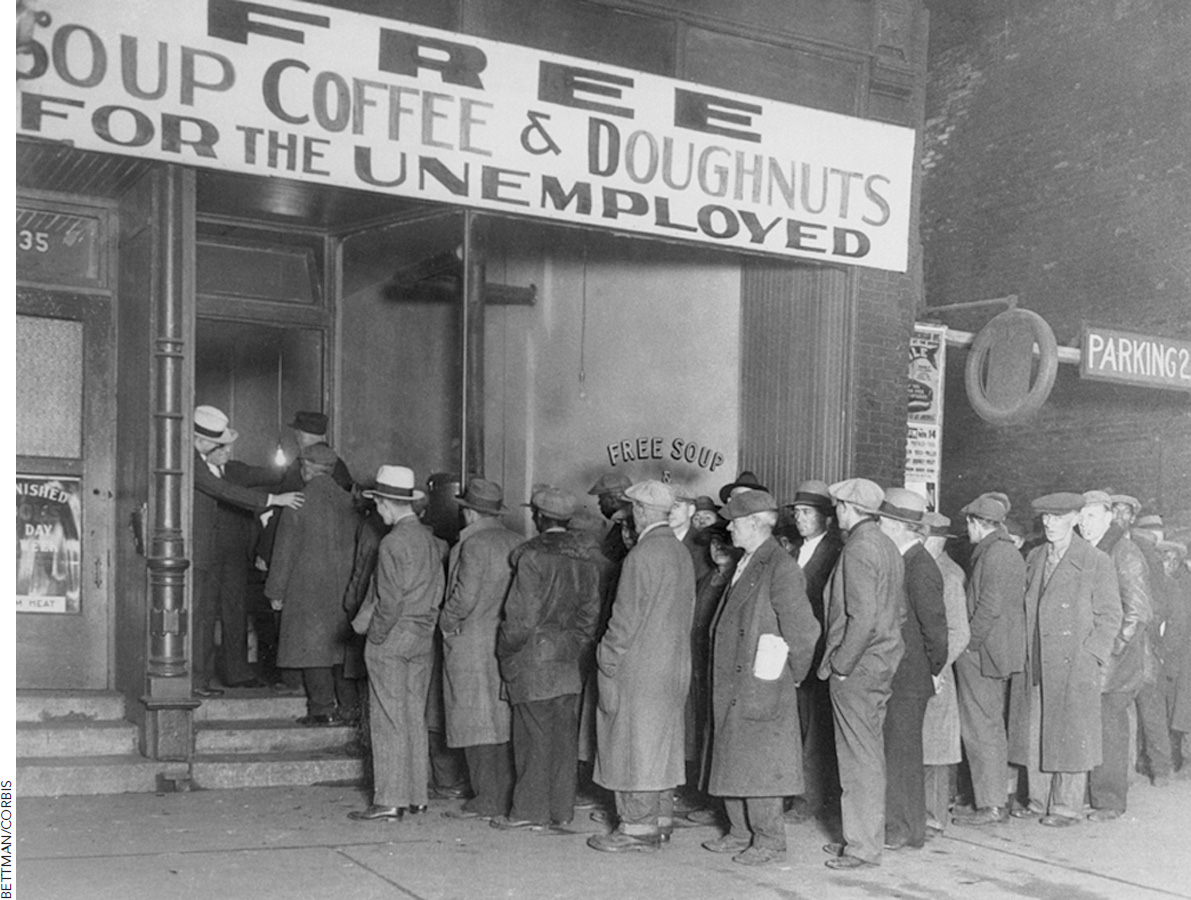

It is also the case—as with monetary policy—that fiscal policy is most effective when the relevant shock is to aggregate demand and there are many unemployed resources. For these reasons, most economists look back on the Great Depression of the 1930s and see expansionary fiscal policy as a good idea in that setting. As we saw in Chapter 13, the Great Depression was primarily caused by a reduction in aggregate demand rather than by a real shock, so increasing aggregate demand was the right type of solution.

Furthermore, at the time, rates of unemployment were sometimes as high as 25%, which meant that the degree of crowding out was probably not very large. Let’s say that the federal government hires some workers to build a dam. If the government is simply pulling already employed workers from other jobs, we shouldn’t expect this to help the economy much. But if those people otherwise would have been out of work, we should expect a greater economic stimulus in the short term. In other words, when it comes to these workers, the government investment is not crowding out alternative private investments. The government investment is creating economic activity in addition to private investments.

In addition, the increase in government spending during the Great Depression was relatively rapid and quite dramatic in percentage terms. Roosevelt, the architect of the New Deal, won the election in 1932. By 1936, federal government spending was more than twice what it had been in 1932.

Notice that today rates of unemployment range more often between 4% and 9%, so increased government spending is likely to draw people from one job to another job rather than from unemployment to work. It would also be more difficult for the federal government to increase spending by as large a percentage as it did in the 1930s. So for these reasons, fiscal policy is less likely to be successful today than it was in the 1930s, and crowding out is more likely to happen.2

Now let’s consider the stimulus under President Obama. For all the talk about the Obama stimulus, the plan is best understood as consisting of three separate parts. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, as approved in February 2009, included $292 billion in federal tax cuts (including increased transfer payments to the poor), $272 billion in direct federal spending, and $223 billion in grants to the governments of the 50 states.

The experiment is not quite over, but so far the consensus seems to be this:

A lot of the tax cuts were saved rather than spent, or used to pay off debts. This boosted economic security for some people but didn’t reemploy a lot of workers.

The grants to the states prevented a large number of state government layoffs. That said, a longer-term problem has been created, whereby many state governments are now dependent on the federal government for their revenue.

The expenditures cover a wide range of ground, ranging from medical research to home insulation to high-speed rail. Some of these will do the world good, but it is not clear that they have targeted unemployed labor very successfully and put many people back to work.

There is also a general sense that the stimulus did not crowd out much private sector capital and investment; interest rates remained at record or near-record lows during stimulus implementation. The crowding out of labor turned out to be the more serious problem. A project such as medical research and development usually will bid for laborers who already have good jobs, whereas a disproportionate share of today’s unemployed have relatively low levels of education.

So let’s sum up when fiscal policy is most likely to matter:

When the economy needs a short-run boost, even at the expense of the long run

When the problem is a deficiency in aggregate demand rather than a real shock

When many resources are unemployed