CHAPTER REVIEW

FACTS AND TOOLS

Question 20.12

1. Start with the facts about the trade deficit (also known as the “balance of trade”), the most widely discussed part of the balance of payments. Head to the database run by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2. In the search box, look for data on two series, EXPGSCA (real annual exports in year 2000 dollars) and IMPGSCA (real annual imports in year 2000 dollars). Below each graph, you should see the raw annual data for the last five years.

What was the level of exports for each of the last five years? Did exports rise every year?

What was the level of imports for each of the last five years? Did imports rise every year? If not, did exports and imports fall at the same time?

How big was the trade deficit (or surplus) each year?

Divide each year’s number by real GDP for each year (GDPCA): What was the trade deficit (or surplus) as a percentage of GDP each year? In years when GDP fell from the previous year, did the trade deficit rise or fall?

Question 20.13

2. Practice with the balance of payments:

Current account + Capital account = Change in official reserves

Current account = -$10, Capital account = +$15. What is the change in reserves?

Current account = -$10, Change in reserves = -$3. What is the capital account?

Your college expenses = $12,000, Income from your barista job = $4,000. What is your current account? If you haven’t changed your reserves (i.e., cash savings) at all, what is the capital account (i.e., borrowing from parents or bank)?

Question 20.14

3.

Consider two headlines: “Foreigners are bringing bags of money to the U.S. to grab property” vs. “Record U.S. trade deficit.” How can both be true simultaneously?

Consider two headlines: “Money is fleeing the U.S. faster than ever” vs. “Record U.S. trade surplus.” How can both be true simultaneously?

Question 20.15

4. In the chapter, two stories about the deficit are told: “the great place to invest” story and the “foolishly saving too little” story. In the following examples, which is more like the “great place to invest” story and which is more like the “foolishly saving too little” story?

Goofus uses his student loan money to buy a nice flat-screen TV and can’t afford most of his textbooks. Gallant uses his student loan money to buy his textbooks and coffee that keeps him awake during study sessions.

Carter borrows money from his dad to attend the right parties, make useful industry connections, and build his career. Ernest borrows money from his dad to attend fun parties, meet fun people, and, well, that’s about it.

America 1 borrows money to invest in her future. America 2 borrows money to pay for a spending binge.

Question 20.16

5.

According to Table 20.1, how many Japanese yen could you get for 1 dollar on September 2010? Use the currency converter on Yahoo! Finance to find out how many yen you could buy for a dollar today.

Given your answer to the previous question, did the dollar gain or lose buying power, in terms of Japanese goods, over this period? (Get this one right: It’s crucial to understanding exchange rates.)

Repeat parts a and b for one other currency in Table 20.1.

Question 20.17

6. According to the purchasing power parity theorem, what must be approximately equal across countries: the nominal exchange rate or the real exchange rate?

Question 20.18

7.

According to purchasing power parity theory, a country with massive inflation should also experience a massive fall in the price of its currency in terms of other currencies (a depreciation). Is this what happened in Zimbabwe, or did the opposite occur?

Hyperinflation is defined as a rapid rise in the price of goods and services. According to purchasing power parity theory, does hyperinflation also cause a rapid rise in the price of foreign currencies?

Question 20.19

8. Which international financial institution focuses on the long-run health of developing countries: the IMF or the World Bank? Which one focuses on short-run financial crises in developing countries?

Question 20.20

9. Let’s translate between newspaper jargon about exchange rates and the economic reality of exchange rates.

Last week, the currency of Frobia was trading one for one with the currency of Bozzum. This week, one unit of Frobian currency buys two units of Bozzumian currency. Which currency “rose”? Which currency became “stronger”? Which currency “appreciated”?

The currency in the nation of Malvolio becomes “weaker.” Now that it’s weaker, can 10 U.S. dollars buy more of the Malvolian currency than before or less than before?

A college student travels from the United States to Germany. Just before he leaves, he changes $400 into euros. He spends only half the money while in Germany, so on his return to the United States, he exchanges his euros back into dollars. However, while he was admiring Munich’s historic Marienplatz, the dollar “weakened” considerably. Is this good news or bad news from the college student’s point of view?

Question 20.21

10.

When the Japanese government slows the rate of money growth, will that tend to strengthen the yen against the dollar or weaken the yen against the dollar?

When the Japanese government slows the rate of money growth, will the dollar tend to appreciate against the yen or will the dollar tend to depreciate against the yen?

When Americans increase their demand for Japanese-made cars, will that tend to strengthen the yen against the dollar or weaken the yen against the dollar?

When Americans increase their demand for Japanese-made cars, will the dollar tend to appreciate against the yen or will the dollar tend to depreciate against the yen?

THINKING AND PROBLEM SOLVING

Question 20.22

1. Practice with the current account: Which of the following tend to raise the value of Country X’s current account?

Country X sends cash to aid war victims in Country Y.

Investors living in Country X receive more dividend payments than usual from businesses operating in Country Y.

Investors living in Country Y receive more interest payments than usual from businesses operating in Country X.

Page 449Immigrants from Country Y who live and work in Country X send massive amounts of currency back to their families in Country Y.

The government of Country X imports more jet fighters and missiles from Country Y.

Question 20.23

2. Practice with the capital account: Which of the three categories of the capital account does each belong in? Which of the following tend to raise the value of Country X’s capital account?

A corporation in Country Y pays for a new factory to be built in Country X.

A corporation in Country Y sells all of its stock in a corporation located in Country X to a citizen of Country X.

A citizen of Country Y purchases 20% of the shares of a corporation in Country X from a citizen of Country X.

A business owner in Country X pays for a new factory to be built in Country Y.

Question 20.24

3. Let’s translate “Americans are foolishly saving too little” into a simple GDP story. Recall that GDP = C + I + G + Net exports. GDP is fixed and equal to 100 throughout the story: After all, it’s pinned down by the production function of Chapter 28. Thus, the size of the pie is fixed: The only question is how the pie is sliced into C, I, G, and net exports. To keep it simple, assume that I + G = 40 throughout.

The “saving too little” story comes in two parts: In part one (now), the United States has high C and low (really, negative) net exports. If C = 70, what do net exports equal? Is this a trade deficit or a trade surplus?

In part two (later), foreign countries are tired of sending so many goods to the United States, and want to start receiving goods from the United States. Net exports now become positive, rising to +5. What does C equal? If citizens value consumption, which period do they prefer: “now” or “later”?

Question 20.25

4. Let’s translate “The United States is a great place to invest” into a simple GDP story. Recall that GDP = C + I + G + Net exports. In this story, foreigners build up the U.S. capital stock by pushing investment (I) above its normal level. Thus, GDP equals 100 in the “now” period but equals 110 in the “later” period. To keep it simple, assume that C + G = 80 throughout.

The “great place to invest” story comes in two parts: In part one (now), the United States has high I and low (really, negative) net exports. If I = 35, what do net exports equal? Is this a trade deficit or a trade surplus?

In part two (later), foreign countries are tired of sending so many machines and pieces of equipment to the United States, and want to start receiving goods from the United States. Net exports now become positive, rising to +5. What does I equal?

Question 20.26

5. The market for foreign currencies is a lot like the market for apples or cars or fish, so we can use the same intuition—as long as we keep reminding ourselves which way is “up” and which is “down.” Consider the market for something called “euros” (maybe it’s a new breakfast cereal) and measure the price in dollars. Discuss the following cases:

The people who make “euros” decide to produce many more of them. Is this a shift in supply or in demand, and in which direction? What does this do to the price of euros?

Consumers and businesses decide that they’d like to own a lot more euros than before. Is this a shift in supply or in demand, and in which direction? What does this do to the price of euros?

There’s a slowdown in the production of euros, initiated by the executives in charge of euro production. Is this a shift in supply or in demand, and in which direction? What does this do to the price of euros?

Suppose that the price of apples rises. Using the same language as in parts a and b, would you describe this as a strengthening of the dollar or a weakening of the dollar?

Question 20.27

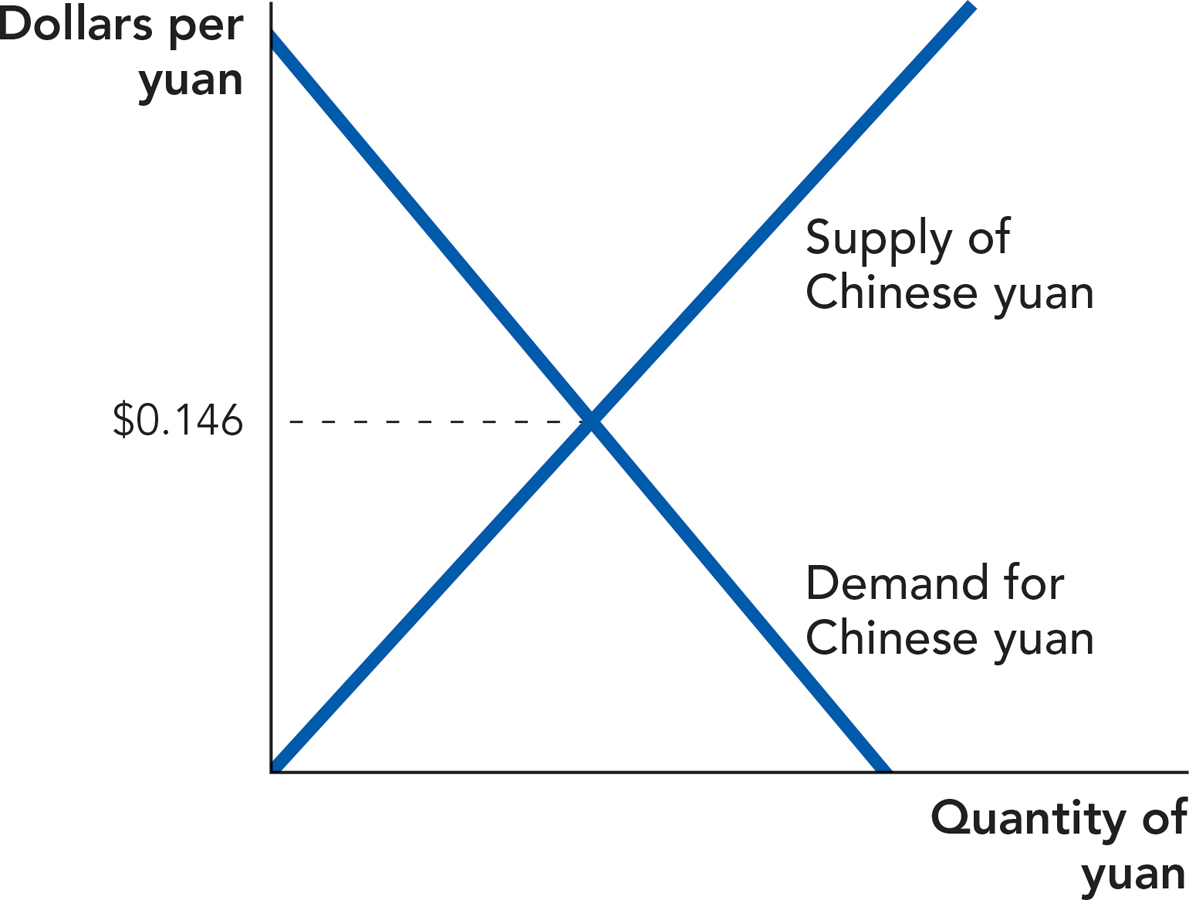

6. Now that we’ve built up some intuition about exchange rates, let’s apply the principles more thoroughly. In this question, we discuss the U.S.—China exchange rate. Officially, the Chinese government fixed this exchange rate for years at a time, but in this question, we treat it as a market rate that can change every day.

In the following figure, shift the appropriate curves to illustrate the effect of the following news story: Chinese factory sells poisonous dog food.

Page 450

Does this news story raise or lower the price of the yuan? Does this strengthen or weaken the Chinese currency? Does this strengthen or weaken the U.S. dollar?

Question 20.28

7. Nobel Laureate Robert Solow once jokingly noted, “I have a chronic [trade] deficit with my barber, who doesn’t buy a darned thing from me.” Is this a problem? Why or why not? How does this relate to the U.S.–China, U.S.–Mexico, and U.S.–Japan trade deficits?

Question 20.29

8. Corey, a young entrepreneur, notices that cigarette lighters sell for only $0.50 each in Utah but they sell for $1.00 each in Nevada.

If Corey wants to make money by buying and selling lighters, where should he buy the lighters and where should he sell them?

If many other people imitate Corey’s behavior, what will happen to the supply of lighters in Utah (rise, fall, unchanged)? What will happen to the supply of lighters in Nevada (rise, fall, unchanged)?

What will the behavior in part b do to the price of lighters in Utah? In Nevada?

According to the law of one price, what can we say about the price of cigarette lighters in Nevada after all of this arbitrage? More than one of the following may be true:

Less than $1.00 each

More than $1.00 each

The same as the Utah price

Question 20.30

9. At Christmas, five-year-old Gwen runs a massive trade deficit with her parents: She “exports” only a wrapped candy cane to her parents, but she “imports” a massive number of video games, dolls, and pairs of socks.

Is this trade deficit a good thing for Gwen?

When Gwen turns 25, her parents insist on being repaid for all those years of Christmas presents—that is, they require her to run a “trade surplus.” Is this “trade surplus” good news for Gwen? Why or why not?

Question 20.31

10.

Suppose that the price level in the United States doubled, while the price level in the U.K. remained unchanged. According to purchasing power parity theory, would the dollar/pound nominal exchange rate double or would it fall in half?

In practice, PPP tends to hold more true in the long run than in the short run, because many prices are sticky. So if the U.S. money supply increased dramatically—a big enough rise for the price level to double in the long run—would this be good news for British tourists headed to the United States or would it be good news for U.S. tourists headed to Britain? Incidentally, would this be good news or bad news (in the short run) for U.S. tourists staying in the United States?

CHALLENGES

Question 20.32

1. In our basic model, a rise in money growth causes currency depreciation: We also know from Chapter 13 and Chapter 16 on monetary policy that a rise in money growth normally raises aggregate demand and boosts short-run real growth. But in the 2001 Argentine crisis and the 1997 Asian financial crisis, a currency depreciation seemed to cause a massive fall in short-run output.

What type of shock could cause a currency depreciation to be associated with a fall in short-run output?

In both the Argentine and the Asian crises, these countries’ banking sectors were hit especially hard: They had made big promises to pay their debts in foreign currencies— often dollars—and the depreciation made it impossible for them to keep those promises. What became more “expensive” as a result of the depreciation: foreign currency (dollars, yen, pounds) or domestic currency?

Page 451In these crises, depreciation created bankruptcies: These bankruptcies are what causes the shock discussed in part a. To avoid this outcome in the future, Berkeley economist Barry Eichengreen, an expert on exchange rate policy, recommended that businesses in developing countries should encourage foreigners to invest in stock that pays dividends rather than in debt. He believed this would make it easier for countries to endure surprise depreciations. Why would he recommend this?

Question 20.33

2. In Panama, a dollarized country, a Big Mac is about 30% cheaper than in the United States. Why?

Question 20.34

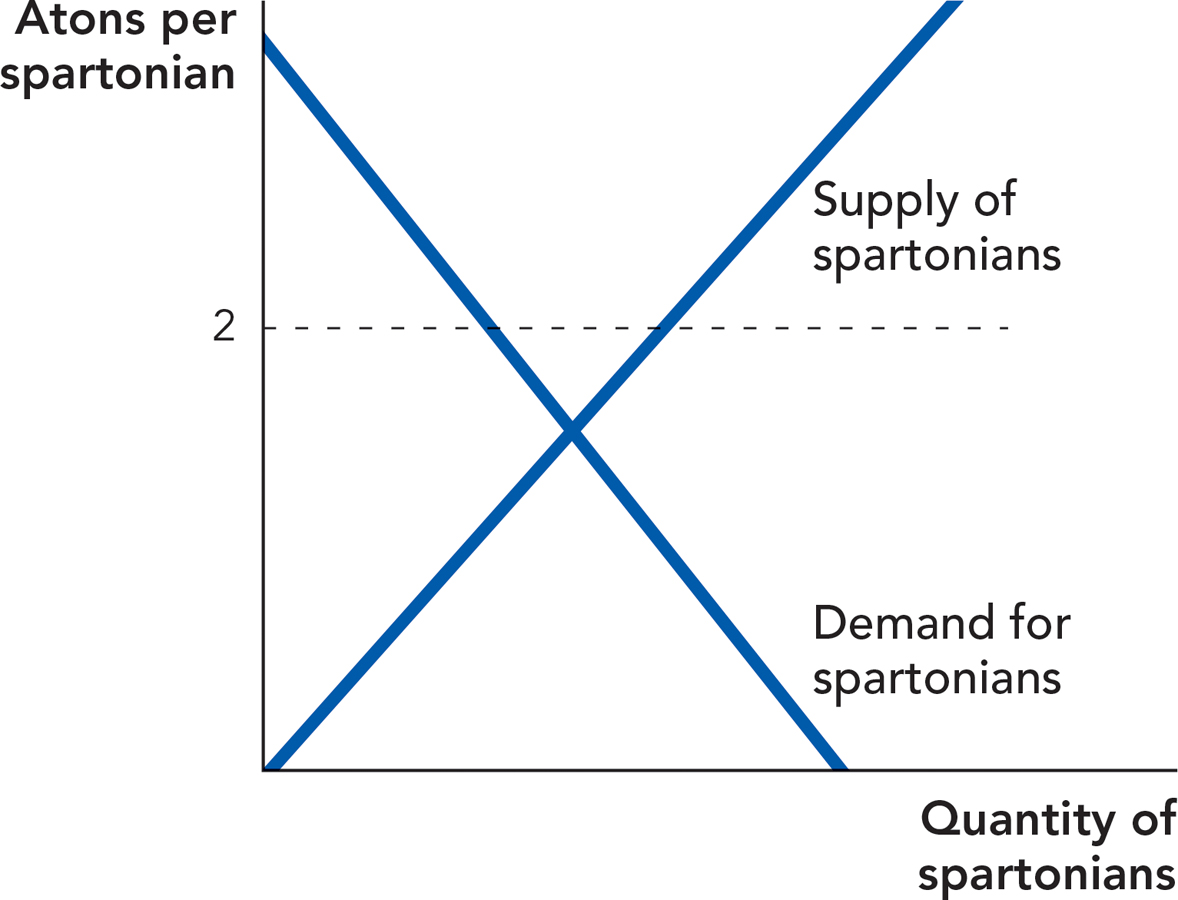

3. A supply-and-demand model can illustrate the difficulty of keeping a fixed exchange rate: It’s much the same as any other price floor. Consider the following fixed exchange rate. Sparta uses a currency called the spartonian, Athenians use the aton, and the Spartans have chosen a fixed exchange rate of two atons per spartonian:

In a typical supply and demand model, what would you call the gap that exists between quantity supplied and quantity demanded at this fixed exchange rate: a surplus or a shortage? Of which currency?

If the Spartan government wants to keep this exchange rate fixed, what will tend to happen to its official reserve account supply of atons: Will it rise, or will it tend to fall? (Hint: Remember that the suppliers of spartonians want to buy atons. How does this explain why governments of fixed exchange rate countries hold large amount of foreign currencies in their accounts?)

If demand for spartonians fell because of a weak Spartan economy, would this make it harder or easier for this government to maintain the exchange rate?

If the Spartan government wanted to bring quantity supplied and quantity demanded closer together, would it want to slow money growth or raise money growth? When real world countries have “overvalued” currencies, do you think they should fix them by slowing money growth or by raising money growth?

Question 20.35

4.

Ecuador is currently dollarized: Bank accounts are denominated in U.S. dollars, for example. If Ecuadoreans believe rumors that the country is going to go off the dollar and convert all bank account deposits into a new unit of money called the “Ecuado” (similar to what Argentina actually did in 2001), what will this probably do to the Ecuadorean banking system?

“There is no such thing as a fixed exchange rate: Just pegs that haven’t been changed … yet.” Explain how this belief, by itself, can make it difficult for a country to maintain a fixed exchange rate. Does this belief have a direct impact on the demand for a currency or on the supply of a currency?

Question 20.36

5. We said that “an effective peg requires a very serious commitment to a high level of monetary and fiscal stability.” As in our discussion of monetary policy, people’s beliefs about what government might do in the future put limits on what governments should do today. Discuss how “commitment” can keep an exchange rate stable. Compare with how commitment can make it easier to keep inflation low. What can a government do in these situations to convince foreign investors and domestic citizens that it will keep its commitments? (Certainly, there is more than one good way to answer this question: The problem of creating commitment is an active area of research across the social sciences.)

WORK IT OUT

Consider two headlines: “Money is pouring into the U.S. faster than ever” vs. “Record U.S. trade deficit.” How can both be true simultaneously?

Consider two headlines: “Money is fleeing the U.S. faster than ever” vs. “Record U.S. trade surplus.” How can both be true simultaneously?

* Other textbooks or sources, however, might put “yen per dollar” (or “yen/$”) instead of “dollars per yen” on the price axis. Either way is correct so long as you remember which one you are working with.