How Monetary and Fiscal Policy Affect Exchange Rates and How Exchange Rates Affect Aggregate Demand

Monetary and fiscal policy will alter the exchange rate and trade balance (exports minus imports) of a country. To understand how, keep in mind that an approximate version of purchasing power parity (for tradable goods) holds in the long run, but that deviations from parity are possible in the short run.

Monetary Policy

Imagine that the Federal Reserve increases  through open market operations, a concept discussed in our chapters on the Federal Reserve and monetary policy. The increase in

through open market operations, a concept discussed in our chapters on the Federal Reserve and monetary policy. The increase in  shifts the supply curve for dollars down and to the right, which will result in a lower exchange rate (a depreciation). In the short run, dollar prices are sticky so as far as the rest of the world is concerned, it’s as if U.S. goods went on sale! Let’s look at this in more detail.

shifts the supply curve for dollars down and to the right, which will result in a lower exchange rate (a depreciation). In the short run, dollar prices are sticky so as far as the rest of the world is concerned, it’s as if U.S. goods went on sale! Let’s look at this in more detail.

Imagine that Caterpillar tractors sell for $50,000 and the exchange rate starts out at 1 euro per dollar so in Europe a Caterpillar tractor costs €50,000. Now suppose that as a result of Fed actions, the exchange rate depreciates so that a European needs only 0.8 euros to buy a dollar. The dollar price is still $50,000, but because of the change in the exchange rate, the price in euros has fallen from €50,000 to €40,000, which is in essence a 20% discount. Thus, a depreciation will increase U.S. exports. Recall from Chapter 13 that an increase in exports increases AD, which boosts the economy in the short run.

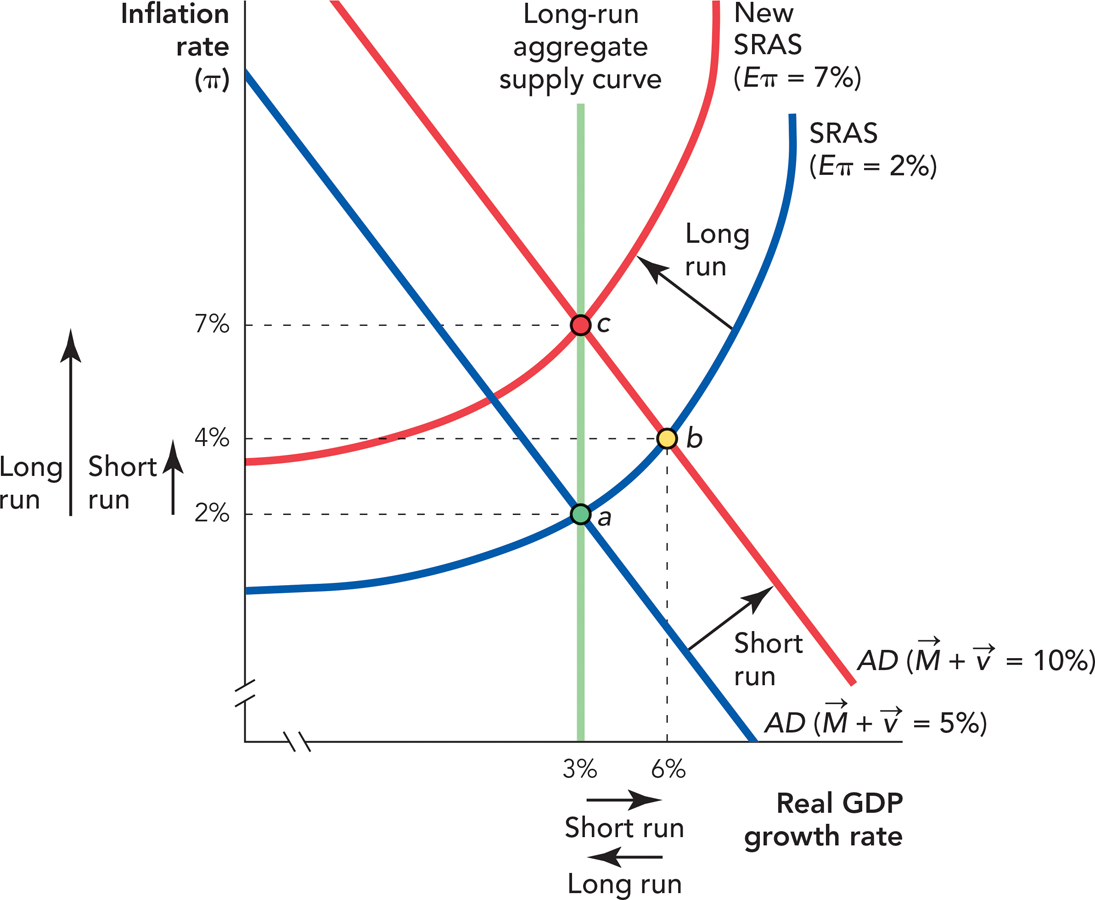

Figure 20.6 shows the process in a diagram. Keep in mind that this is exactly the same analysis of an increase in aggregate demand that we discussed in Chapter 13 and also in the chapters on monetary and fiscal policy. The only difference is that the source of the shift in AD is now a depreciation in the exchange rate; the mechanics are exactly as before.

FIGURE 20.6

The economy begins at point a in long-run equilibrium. The increase in M causes a depreciation in the exchange rate, which in turn reduces the price of U.S. exports. As a result, exports increase, AD increases, and the growth rate of the economy increases, moving the economy in the short run to point b. But what about the long run?

In the long run, money is neutral, which means that domestic prices will rise to match the increase in  . As a result, the nominal exchange rate will be lower but the real exchange rate—in the long run—won’t have changed much, if at all. So, in the long run the real depreciation (the sale on U.S. exports) proves to be temporary and so the boost in exports is temporary as well. But if the increase in

. As a result, the nominal exchange rate will be lower but the real exchange rate—in the long run—won’t have changed much, if at all. So, in the long run the real depreciation (the sale on U.S. exports) proves to be temporary and so the boost in exports is temporary as well. But if the increase in  is not reversed, the U.S. inflation rate increases. Thus, in the long run, the economy moves from point b to point c and the boost to real output growth is not permanent.

is not reversed, the U.S. inflation rate increases. Thus, in the long run, the economy moves from point b to point c and the boost to real output growth is not permanent.

We can, however, see one additional reason why politicians and central banks sometimes favor increases in the growth rate of money  . An increase in

. An increase in  usually will boost a nation’s exports and thus employment. It will appear the economy is doing better, at least for a little while but, as usual, the boost to the economy is temporary and it raises the possibility of higher inflation rates.

usually will boost a nation’s exports and thus employment. It will appear the economy is doing better, at least for a little while but, as usual, the boost to the economy is temporary and it raises the possibility of higher inflation rates.

Furthermore, although the depreciation makes exports cheaper, it makes imports more expensive. The diminished ability of the nation to invest abroad at good prices or buy imports at good prices—because of the lower real exchange rate—is a less visible but real cost of the lower real exchange rate. The lower real exchange rate nonetheless represents a political temptation, if only because the economy at least appears stronger when exports increase in the short run.

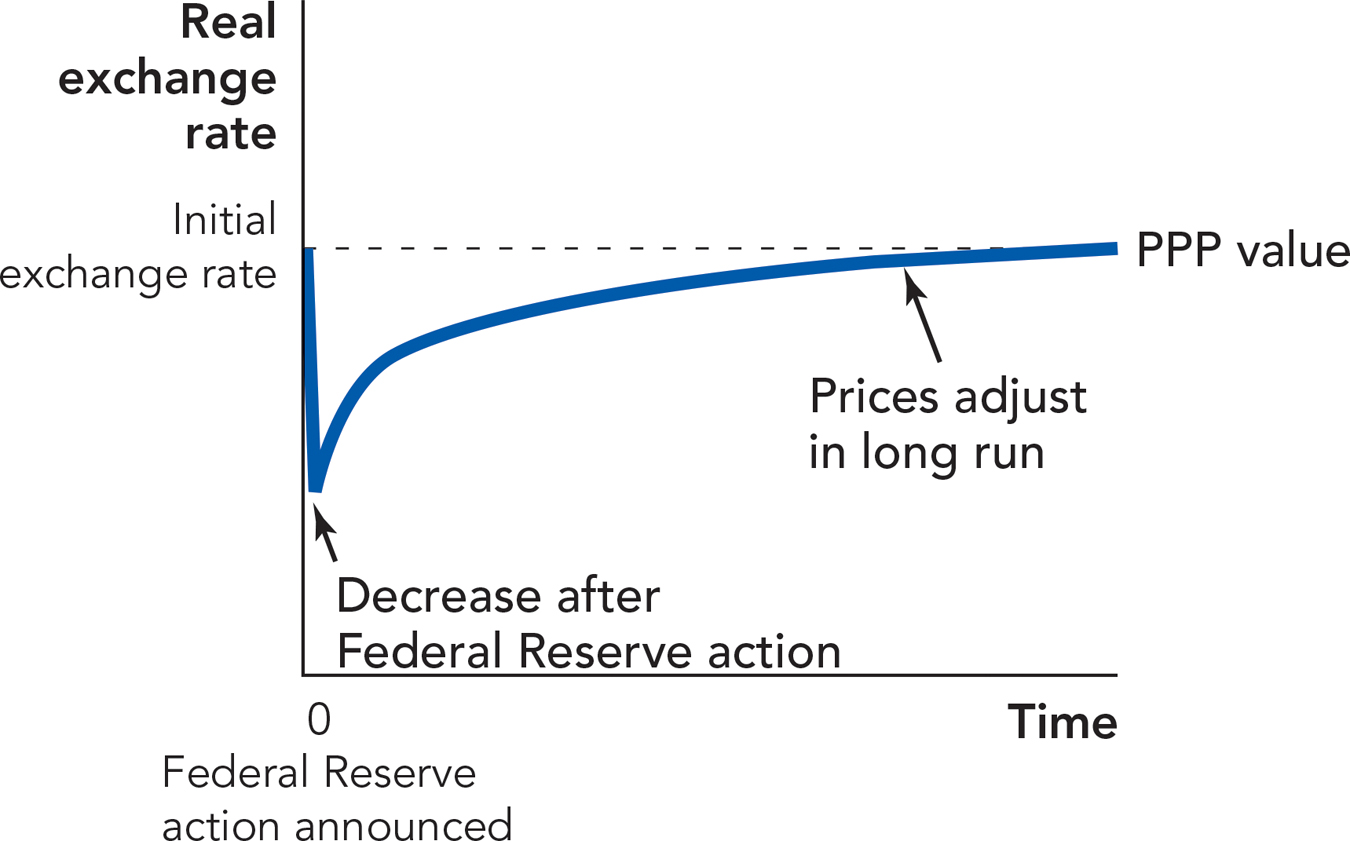

That’s it for aggregate output. When it comes to the real exchange rate itself, the path of the market to equilibrium looks like the one portrayed in Figure 20.7. Once a Fed action is announced, the dollar moves on international currency markets within seconds. Prices for most goods and services, even if they are relatively flexible, do not respond with this speed. So, at first the dollar has lower international value in real terms.

FIGURE 20.7

increases the supply of dollars, thus causing a depreciation in the nominal exchange rate. Domestic prices are sticky so at first the nominal depreciation is also a real depreciation. Over time, however, domestic prices rise, so in the long run the real exchange rate returns to its fundamental value as determined by approximate purchasing power parity.

increases the supply of dollars, thus causing a depreciation in the nominal exchange rate. Domestic prices are sticky so at first the nominal depreciation is also a real depreciation. Over time, however, domestic prices rise, so in the long run the real exchange rate returns to its fundamental value as determined by approximate purchasing power parity.For a decrease in  , the process is the reverse. In the short run, the real exchange rate will appreciate, causing U.S. exports to be more expensive on world markets. In the long run, the real exchange rate will be reestablished at the approximate PPP value. Notice that we can see once again why nations with a high rate of inflation—nations that ought to lower

, the process is the reverse. In the short run, the real exchange rate will appreciate, causing U.S. exports to be more expensive on world markets. In the long run, the real exchange rate will be reestablished at the approximate PPP value. Notice that we can see once again why nations with a high rate of inflation—nations that ought to lower  —may be reluctant to do so. In the short run, a reduction in

—may be reluctant to do so. In the short run, a reduction in  reduces exports, reducing AD and reducing the real growth rate in the short run.

reduces exports, reducing AD and reducing the real growth rate in the short run.

Fiscal Policy

Expansionary fiscal policy, or an increase in the budget deficit, will raise domestic interest rates. As explained in Chapter 9 and Chapter 18, when government borrows more money, the demand for loanable funds shifts outward and interest rates go up.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 20.8

In the short run, what will happen to exports if the Fed increases the money supply? What will happen in the long run?

In the short run, what will happen to exports if the Fed increases the money supply? What will happen in the long run?

Question 20.9

Which tends to be more effective in an open economy: monetary policy or fiscal policy?

Which tends to be more effective in an open economy: monetary policy or fiscal policy?

As a result, the higher interest rates will cause the nation—let’s say the United States—to run a greater surplus on its capital account. That is, more foreigners will want to invest in the United States to enjoy those high interest rates. The greater demand to invest will cause an appreciation of the U.S. dollar. What does an appreciation of the dollar do to U.S. exports? An appreciation makes U.S. exports more expensive, thus reducing U.S. exports. Thus, a budget deficit can cause a trade deficit. These are sometimes called “the twin deficits.”

We now see one more limitation of fiscal policy. The boost to domestic aggregate demand, resulting from the new government spending, will to some extent be offset by the greater difficulty of exporting at the new and higher real exchange rate. Total aggregate demand—domestic plus foreign—might not go up at all. In other words, the argument for fiscal policy discussed in Chapter 18 is less justified the more open the economy. This is yet another reason why monetary policy has typically become more important than fiscal policy as a tool of macroeconomic management.