Two Cheers for Democracy

You might be wondering by now: Why isn’t everything from the federal government handed out to special interest groups and why aren’t politicians always reelected? Do the voters ever get their way? In fact, voters in a democracy can be very powerful. If you want to think about when voters matter most and when lobbies and special interests matter most, turn to the idea of incentives.

When a policy is specialized in its impact, difficult to understand, and affects a small part of the economy, it is likely that lobbies and special interests get their way. Let’s say the question is whether the depreciation deduction in the investment tax credit should be accelerated or decelerated. Even though this issue is important to many powerful corporations, you can expect that most voters have never heard of the issue and that it will be settled behind closed doors by a relatively small number of people.

But when a policy is highly visible, appears often in the newspapers and on television, and has a major effect on the lives of millions of Americans, the voters are likely to have an opinion. The point isn’t that voter opinions are always well informed or rational, but that voters do care about some of the biggest issues such as Social Security, Medicare, and taxes and when they do care, politicians have an incentive to serve them. But how exactly does voter opinion translate into policy? After all, opinions are divided, so which voters will get their way in a democracy?

The Median Voter Theorem

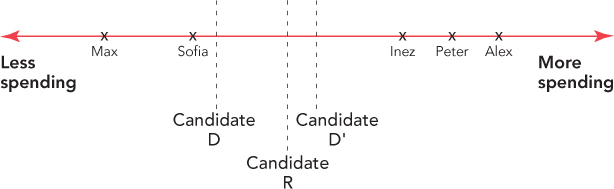

To answer this question, we develop a model of voting called the “median voter model.” Imagine that there are five voters, each of whom has an opinion about the ideal amount of spending on Social Security. Max wants the least spending, followed by Sofia, Inez, Peter, and finally Alex, who wants the most spending. In Figure 20.3, we plot each voter’s ideal policy along a line from least to most spending. We also assume that each voter will vote for the candidate whose policy position is closest to his or her ideal point.

The median voter is defined as the voter such that half of the other voters want more spending and half want less spending. In this case, the median voter is Inez, since compared with Inez, half of the voters (Paul and Alex) want more spending and half the voters (Max and Sofia) want less spending.

The median voter theorem says that when voters vote for the policy that is closest to their ideal point on a line, then the ideal point of the median voter will beat any other policy in a majority rule election.

The median voter theorem says that under these conditions, the median voter rules! Or to put it more formally, the median voter theorem says that when voters vote for the policy that is closest to their ideal point on a line, then the ideal point of the median voter will beat any other policy in a majority rule election.

Let’s see why this is true and, as a result, how democracy will tend to push politicians toward the ideal point of the median voter. First, consider any two policies such as those adopted by Candidate D and Candidate R. Which policy will win in a majority rule election? Max and Sofia will vote for Candidate D since D’s policy is closer to their ideal point than R’s policy. But Inez, Peter, and Alex will vote for Candidate R. By majority rule, Candidate R will win the election. Notice that, of the two policies offered, the policy closest to that of the median voter’s ideal policy won the election.

FIGURE 20.3

Most politicians don’t like to lose. So in the next election Candidate D may shift her position, becoming Candidate D?. By exactly the same reasoning as before, Candidate D? will now win the election. If we repeat this process, the only policy that is not a sure loser is the ideal point of the median voter (Inez). As Candidates D and R converge on the ideal point of the median voter, there will be little difference between them and each will have a 50% chance of winning the election.*

The median voter theorem can be interpreted quite generally. Instead of thinking about less spending and more spending on Social Security, for example, we can interpret the line as the standard political spectrum of left to right. In this case, the median voter theorem can be interpreted as a theory of democracy in a country such as the United States where there are just two major parties.

The median voter theorem tells us that in a democracy, what counts are noses—the number of voters—and not their positions per se. Imagine, for example, that Max decided he wanted even less spending or that Alex decided he wanted even more spending. Would the political outcome change? No. According to the median voter theorem, the median voter rules, and if the median voter doesn’t change, then neither does policy. Thus, under the conditions given by the median voter theorem, democracy does not seek out consensus or compromise or a policy that maximizes voter preferences, on average—it seeks out a policy that cannot be beaten in a majority rule election.

The median voter theorem does not always apply. The most important assumption we made was that voters will vote for the policy that is closest to their ideal point. That’s not necessarily true. If no candidate offers a policy close to Max’s ideal point, he may refuse to vote for anyone, not even the candidate whose policy is (slightly) closer to his own ideal. In this case, a candidate who moves too far away from the voters on her wing may lose votes even if her position moves closer to that of the median voter. As a result, this type of voter behavior means that candidates do not necessarily converge on the ideal point of the median voter.

We have also assumed that there is just one major dimension over which voting takes place. That’s not necessarily true either. Suppose that voters care about two issues, such as taxes and war, and assume that we cannot force both issues into a left-right spectrum (so knowing a person’s views about taxes doesn’t necessarily predict much about his or her views about war). With two voting dimensions, it’s very likely that there is no policy that beats every other policy in a majority rule contest, so politics may never converge on a stable policy.

To understand why a winning policy sometimes doesn’t exist, consider an analogy from sports. Imagine holding a series of (hypothetical) boxing matches to figure out who is the greatest heavyweight boxer of all time. Suppose that Muhammad Ali beats Lennox Lewis and Lewis beats Mike Tyson but Tyson beats Muhammad Ali. So who is the greatest of all time? The question may have no answer if there is more than one dimension to boxing skill, so Ali has the skills needed to beat Lewis and Lewis has the skills needed to beat Tyson, but Tyson has the skills to beat Ali. In a similar way, when there is more than one dimension to politics, no policy may exist that beats every other policy. In terms of politics, the result may be that every vote or election brings a new winner, or alternatively, constitutions and procedural restrictions may slow down the rate of political change. The U.S. Constitution, for example, requires that new legislation must pass two houses of Congress and evade the president’s veto, which is more difficult than passing a simple majority rule vote.

As a predictive theory of politics, the median voter theorem is applicable in some but not all circumstances. The theorem, however, does remind us that politicians have substantial incentives to listen to voters on issues that the voters care about. This is a powerful feature of democracy, although of course the quality of the democracy you get will depend on the wisdom of the voters behind it.

Democracy and Nondemocracy

Our picture of democracy so far has been a little disillusioning, at least compared with what you might have learned in high school civics. Yet when we look around the world, democracies tend to be the wealthiest countries, and despite the power of special interests, they also tend to be the countries with the best record for supporting markets, property rights, the rule of law, fair government, and other institutions that support economic growth.

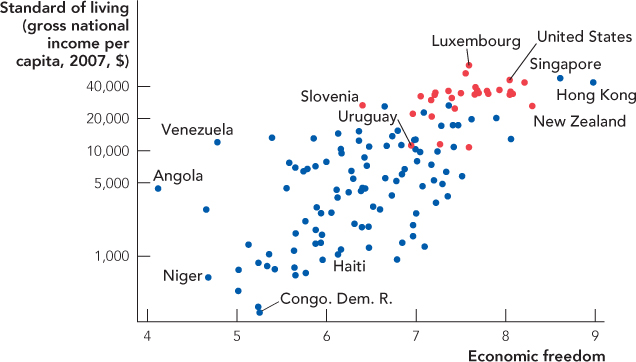

Figure 20.4 graphs an index meant to capture good economic policy, called the economic freedom index (with higher numbers indicating greater economic freedom) on the horizontal axis against a measure of the standard of living on the vertical axis (gross national income per capita in 2007). The figure shows two things. First, there is a strong correlation between economic freedom and a higher standard of living. Second, the countries that are most democratic (labeled “Full democracies” and shown in red) are among the wealthiest counties in the world and the countries with the most economic freedom. The only interesting exceptions to this rule are Singapore and Hong Kong, both of which score very highly on economic freedom and the standard of living but that are not quite full democracies.

FIGURE 20.4

Sources: Economic freedom index from Gwartney, J., R. Lawson, and S. Norton. 2008. Economic Freedom of the World: 2008 Annual Report. Vancouver, BC: The Fraser Institute. Gross national income per capita (2007) from the World Bank.

Note: GNI per capita on ratio scale.

Note: Full democracies are in red.

Notice, however, that in part there is an association between democracy and the standard of living because greater wealth creates a greater demand for democracy. When citizens have satisfied their basic needs for food, shelter, and security, they demand more cerebral goods, such as the right to participate in the political process. This is exactly what happened in South Korea and Taiwan, two countries that became more democratic as they grew wealthier. Many people think that China may become a more democratic country as it grows wealthier; we will see. But it’s not just that wealth brings democracy. Democracy also seems to bring wealth and favorable institutions. Democracies must be doing something right. We therefore need to examine some of the benefits of democratic decision making.

We’ve already discussed rational ignorance under democracy, but keep in mind that public ignorance is often worse in nondemocracies.4 In many quasi democracies and in nondemocracies, the public is not well informed because the media are controlled or censored by the government.

In Africa, for example, most countries have traditionally banned private television stations. In fact as of 2000, 71% of African countries had a state monopoly on television broadcasting. Most African governments also control the largest newspapers in the country. Government ownership and control of the media are also common in most Middle Eastern countries and, of course, the former Communist countries controlled the media extensively.

Control of the media has exactly the effects that we would expect from our study of rational ignorance in democracies—it enables special interests to control the government for their own ends. Greater government ownership of the press, for example, is associated with lower levels of political rights and civil liberties, worse regulation (more policies like price controls that economists think are ineffective and wasteful), higher levels of corruption, and a greater risk of property confiscation. The authors of an important study of media ownership conclude that “government ownership of the press restricts information flows to the public, which reduces the quality of the government.”5

Citizens in democracies may be “rationally ignorant,” but on the whole they are much better informed about their governments than citizens in quasi democracies and nondemocracies. Moreover, in a democracy, citizens can use their knowledge to influence public policy at low cost by voting. In a democracy, knowledge is power. In nondemocracies, knowledge alone is not enough because intimidation and government violence create steep barriers to political participation. Many people just give up or become cynical. Other citizens in nondemocracies fall prey to propaganda and come to accept the regime’s portrait of itself as a great friend of the people.

The importance of knowledge and the power to vote for bringing about better outcomes is illustrated by the shocking history of mass starvation.

Democracy and Famine

At first glance, the cause of famine seems obvious—a lack of food. Yet the obvious explanation is wrong or at least drastically incomplete. Mass starvations have occurred during times of plenty, and even when lack of food is a contributing factor, it is rarely the determining factor of whether mass starvation occurs.

Many of the famines in recent world history have been intentional. When Stalin came to power in 1924, for example, he saw the Ukrainians, particularly the relatively wealthy independent farmers known as kulaks, to be a threat. Stalin collectivized the farms and expropriated the land of the kulaks, turning them out of their homes and sending hundreds of thousands to gulag prisons in Siberia.

Agricultural productivity in Ukraine plummeted under forced collectivization and people began to starve. Nevertheless, Stalin continued to ship food out of Ukraine. Peasants who tried to escape starving regions were arrested or turned back at the border by Stalin’s secret police. Desperate Ukrainians ate dogs, cats, and even tree bark. Millions died.6

The starvation of Ukraine was intentional and it’s clear that it would not have happened in a democracy. Stalin did not need the votes of the Ukrainians and thus they had little power to influence policy. Democratically elected politicians will not ignore the votes of millions of people.

Even unintentional mass starvations can be avoided in democracies. The 1974 famine in Bangladesh was not on the scale of that in Ukraine, but still 26,000 to 100,000 people died of mass starvation. It was probably the first televised starvation, and it illustrates some important themes in the relationship between economics and politics.

Floods destroyed much of the rice crop of 1974 at the same time as world rice prices were increasing for other reasons. The flood meant that there was no work for landless rural laborers who in ordinary years would have been employed harvesting the rice.

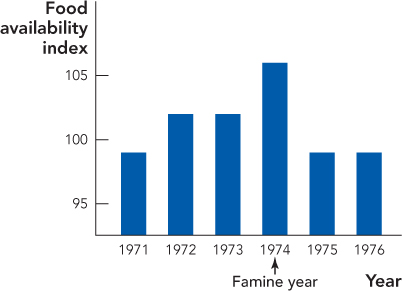

The lower income from work and the higher rice prices, taken together, led to starvations. Yet in 1974, Bangladesh in the aggregate did not lack for food. In fact, food per capita in 1974 was at an all-time high, as shown in Figure 20.5.

FIGURE 20.5

Source: Sen, Amartya. 1990. Public Action to Remedy Hunger. Arturo Tanco Memorial Lecture given in London on August 25, 1990.

Mass starvation occurred not because of a lack of food per se, but because a poor group of laborers lacked both economic and political power. Lack of economic power meant they could not purchase food. Lack of political power meant that the elites then running Bangladesh were not compelled to avert the famine. Bangladesh continued to pursue bad economic policies; for instance, government regulations made it very difficult to purchase foreign exchange so it wasn’t easy for capitalists to import rice from nearby Thailand or India. In fact, rice was even being smuggled out of Bangladesh and into India to avoid price controls and other regulations.

Amartya Sen, the Nobel Prize–winning economist and philosopher, has argued that whether a country is rich or poor, “no famine has taken place in the history of the world in a functioning democracy.” The precise claim can be disputed depending on how one defines “functioning democracy” but the lesson Sen draws is correct:

Perhaps the most important reform that can contribute to the elimination of famines, in Africa as well as in Asia, is the enhancement of democratic practice, unfettered newspapers and—more generally—adversarial politics.7

JUPITERIMAGES/COMSTOCK IMAGES/ALAMY

DESHAKALYAN CHOWDHURY/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Economists Timothy Besley and Robin Burgess have tested Sen’s theory of democracy, newspapers, and famine relief in India.8 India is a federal democracy with 16 major states. The states vary considerably in their susceptibility to food crises, newspaper circulation, education, political competition, and other factors.

Besley and Burgess ask whether state governments are more responsive to food crises when there is more political competition and more newspapers. Note that both of these factors are important. Newspapers won’t work without political competition and political competition won’t work without newspapers. Knowledge and power together make the difference.

Besley and Burgess find that greater political competition is associated with higher levels of public food distribution. Public food distribution is especially responsive in election and preelection years. In addition, as Sen’s theory predicts, government is more responsive to a crisis in food availability when newspaper circulation is higher. That is, when food production falls or flood damage occurs, governments increase food distribution and calamity relief more in states where newspaper circulation is higher. Newspapers and free media inform the public and spur politicians to action.

Democracy and Growth

Democracies have a good record for not killing their own citizens or letting them starve to death. Not killing your own citizens or letting them starve may seem like rather a low standard, but many governments have failed to meet this standard so we count this accomplishment as a serious one favoring democracies. Democracies also have a relatively good record for supporting markets, property rights, the rule of law, fair government, and other institutions that promote economic growth, as shown in Figure 20.4.

One reason for the good record of democracies on economic growth may be that the only way the public as a whole can become rich is by supporting efficient policies that generate economic growth. In contrast, small (nondemocratic) elites can become rich by dividing the pie in their favor even if it means making the pie smaller.

Let’s first recall why small groups can become rich by dividing the pie in their favor even when this means the pie gets smaller. Recall the special interest group that we discussed earlier that made up 1% of the population. Consider a policy that transfers $100 to the special interest at a cost of $4,000 to society. Will the group lobby for the policy? Yes, because the group gets $100 in benefits but it bears only $40 of the costs (1% of $4,000).

By definition, oligarchies or quasi democracies are ruled by small groups. Thus, the rulers in these countries don’t have much incentive to pay attention to the larger costs of their policies as borne by the broader public. The incentives of ruling elites may even be to promote and maintain policies that keep their nations poor. An entrenched, nondemocratic elite, for example, might not want to support mass education. Not only would a more educated populace compete with the elite, but an informed people might decide that they don’t need the elite any more and, of course, the elite know this. As a result, the elites will often want to keep the masses weak and uninformed, neither of which is good for economic growth or, for that matter, preventing starvation.

But now let’s think about a special interest that represents 20% of society. Will this special interest be in favor of a policy that transfers $100 to it at a cost of $4,000 to society? No. The special interest gets $100 in benefits from the transfer but its share of the costs is now $800 (20% of $4,000), so the policy is a net loser even for the special interest. Thus, the larger the group, the greater the group’s incentives to take into account the social costs of inefficient policies.

Large groups are more concerned about the cost to society of their policies simply because they make up a large fraction of society. Thus, large groups tend to favor more efficient policies. In addition, the more numerous the group in charge, the less lucrative transfers are as a way to get rich. A small group has a big incentive to take $1 from 300 million people and transfer it to themselves. But a group of 100 million that takes $1 from each of the remaining 200 million gets only $2 per person. Even if you took one hundred times as much, $100, from each of the 200 million people and gave it to the 100 million, that’s only $200 each. Pretty small pickings. It’s usually better for a large group to focus on policies that increase the total size of the pie.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 20.5

The free flow of ideas helps markets to function. How does the free flow of ideas help democracies to function?

The free flow of ideas helps markets to function. How does the free flow of ideas help democracies to function?

In other words, the greater the share of the population that is brought into power, the more likely that policies will offer something for virtually everybody, and not just riches for a small elite.

The tendency for larger groups to favor economic growth is no guarantee of perfect or ideal policies, of course. As we have seen, rational ignorance can cause trouble. But on the big questions, a democratic leader simply will not want to let things become too bad. That’s a big reason why democracies tend to be pretty good—although not perfect—for economic growth.