Subsidies

A subsidy is a reverse tax: Instead of taking money away from consumers (or producers), the government gives money to consumers (or producers). The close connection between subsidies and taxes means that their effects are analogous. We emphasize the following facts about commodity subsidies:

Who gets the subsidy does not depend on who gets the check from the government.

Who benefits from a subsidy does depend on the relative elasticities of demand and supply.

Subsidies must be paid for by taxpayers and they create inefficient increases in trade (deadweight loss).

With a tax, the price paid by the buyers exceeds the price received by sellers. A subsidy reverses this relationship so the price received by sellers exceeds the price paid by buyers, the difference being the amount of the subsidy. In other words:

The subsidy = Price received by sellers - Price paid by buyers

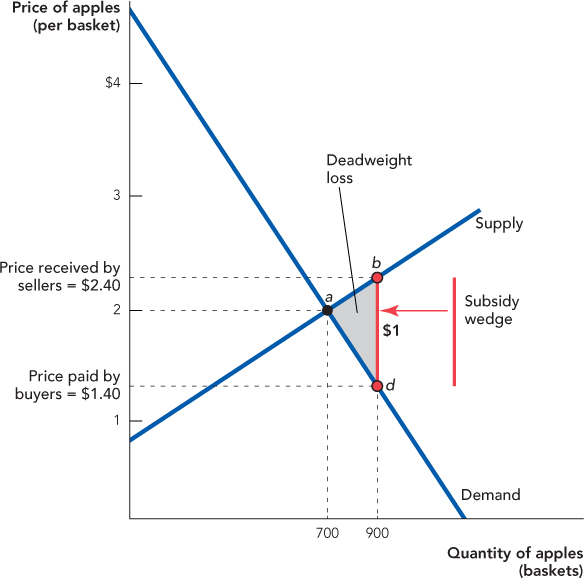

We can analyze subsidies using the same wedge shortcut as before, except now we push the wedge from the right side of the diagram toward the left side. In Figure 6.7, we show that with a $1 subsidy, sellers of apples will receive $2.40 per basket, but buyers will pay only $1.40, the difference of $1 being the subsidy amount.

A subsidy means that the sellers are receiving more than buyers are paying, so who is making up the difference? Taxpayers. The cost to taxpayers is the amount of the subsidy times the number of units subsidized. In Figure 6.7: $1 × 900 or $900.

Just like a tax, a subsidy also creates a deadweight loss. A tax creates a deadweight loss because with the tax, some beneficial trades fail to occur. A subsidy creates a deadweight loss for the reverse reason: With the subsidy, some nonbeneficial trades do occur. In Figure 6.7, notice that for the baskets between 700 and 900, the supply curve lies above the demand curve (i.e., line segment ab lies above line segment ad). The height of the supply curve tells us the cost of producing these baskets. The height of the demand curve tells us the value of these baskets to buyers. Producing baskets for which the cost exceeds the value creates waste, a deadweight loss measured by the triangle abd. In other words, the resources used to produce those extra baskets have an opportunity cost, and they could produce more value in some other part of the economy.

FIGURE 6.7

As with taxes, the wedge analysis shows that it doesn’t make a difference whether buyers are subsidized $1 for every unit bought or sellers are subsidized $1 for every unit sold.

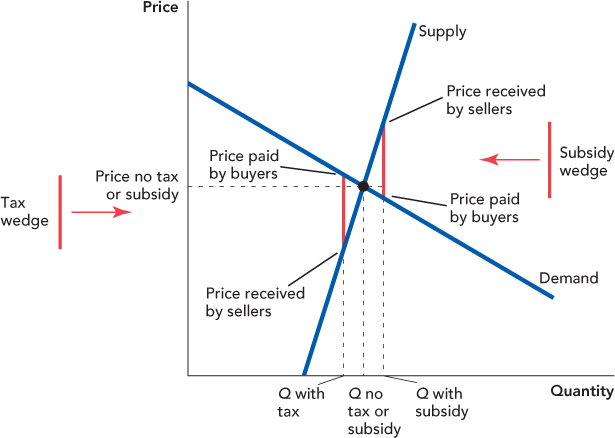

Similarly, we showed that who bears the burden of a tax depends on the relative elasticities of supply and demand. Exactly the same forces determine who gets the benefit of a subsidy. The rule is simple: Whoever bears the burden of a tax receives the benefit of a subsidy. Figure 6.8 illustrates the intuition for the case where the elasticity of supply is less than the elasticity of demand. In this case, suppliers bear the burden of the tax but receive the benefit of a subsidy.

Let’s analyze two examples of subsidies in action.

King Cotton and the Deadweight Loss of Water Subsidies

In California, Arizona, and other western states, there are very large subsidies to water used in agriculture. In California, for example, cotton, alfalfa, and rice farmers in the Central Valley area typically pay $20–$30 an acre-foot for water that costs $200–$500 an acre-foot (an acre-foot is the amount of water needed to cover 1 acre 1 foot deep). The difference is made up by a government subsidy.

Farmers use the subsidized water to transform desert into prime agricultural land. But turning a California desert into cropland makes about as much sense as building greenhouses in Alaska! America already has plenty of land on which cotton can be grown cheaply. Spending billions of dollars to dam rivers and transport water hundreds of miles to grow a crop that can be grown more cheaply in Georgia is a waste of resources, a deadweight loss. The water used to grow California cotton, for example, has much higher value producing silicon chips in San Jose or as drinking water in Los Angeles than it does as irrigation water.

Recall from Chapter 4 that one of the conditions for maximizing the gains from trade in a free market is that there are no wasteful trades. We can now see how in some situations a subsidy can create wasteful trades.

The waste created by water subsidies is compounded with a variety of agricultural subsidies. Some farmers in the Central Valley are “double-dippers”—they use subsidized water to grow subsidized cotton. Some are even “triple-dippers”—they use subsidized water to grow subsidized corn to feed cows to produce subsidized milk!

Who benefits from the water subsidy? Is it California cotton suppliers or cotton buyers? Remember that suppliers receive more of the benefit of a subsidy than buyers when the elasticity of demand is greater than the elasticity of supply (as in Figure 6.8). Can you explain why the elasticity of demand for California cotton is much greater than the elasticity of supply? The elasticity of demand for California cotton is very high since cotton grown elsewhere is almost a perfect substitute. In other words, the price of cotton is determined on the world market for cotton, and California production is too small to have much of an influence on the world price. It’s not surprising, therefore, that it’s not cotton consumers who lobby for water subsidies but the farmers in California’s Central Valley. Central Valley California farmers are politically powerful and they have been subsidized since 1902!

FIGURE 6.8

Wage Subsidies

It’s difficult to see why California cotton should be subsidized when cotton from Georgia (or India, China, or Pakistan) is just as good, but subsidies are not always bad for social welfare. Just as a tax might be beneficial if it reduced smoking, a subsidy might be beneficial if it increased something of special importance (see Chapter 10 for more on when taxes and subsidies might be beneficial). Nobel Prize winner Edmund Phelps, for example, is a strong advocate of using wage subsidies to increase the employment of low-wage workers.

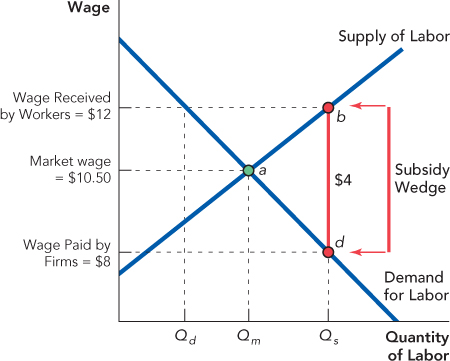

In Phelps’s plan, firms would be subsidized for every low-wage worker that they hire. A subsidy makes hiring a low-wage worker even cheaper, thus increasing the demand for labor. In Figure 6.9, a wage subsidy increases the wage received by workers and decreases the wage paid by firms so employment increases from Qm to Qs.

Wage subsidies can be costly. The cost of the subsidy is the subsidy amount ($4 in Figure 6.9) times the number of workers who are hired under this program (Qs in Figure 6.9). Wage subsidies, however, could have offsetting benefits to taxpayers, making their total cost less than it first appears. Phelps argues, for example, that if wages and employment among low-skilled workers were higher, welfare payments would be lower. He also suggests that encouraging work among those with the least skills would reduce crime, drug dependency, and the culture of so-called rational defeatism that keeps many people in poverty.

FIGURE 6.9

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 6.4

To promote energy independence, the U.S. government provides a subsidy to corn growers if they convert the corn to ethanol, a fuel used in some cars. Because of this subsidy, what happens to the quantity supplied of ethanol, and what happens to the price received by corn growers and the price paid by ethanol buyers?

To promote energy independence, the U.S. government provides a subsidy to corn growers if they convert the corn to ethanol, a fuel used in some cars. Because of this subsidy, what happens to the quantity supplied of ethanol, and what happens to the price received by corn growers and the price paid by ethanol buyers?

Question 6.5

The U.S. government subsidizes college education in the form of Pell grants and lower-cost government Stafford loans. How do these subsidies affect the price of college education? Which is relatively more elastic: supply or demand? Who benefits the most from these subsidies: suppliers (colleges) or demanders of education (students)?

The U.S. government subsidizes college education in the form of Pell grants and lower-cost government Stafford loans. How do these subsidies affect the price of college education? Which is relatively more elastic: supply or demand? Who benefits the most from these subsidies: suppliers (colleges) or demanders of education (students)?

The United States does have one program that is similar to a wage subsidy. It’s called the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). The EITC is a cash subsidy to the earnings of low-income workers. The main difference between the EITC and a Phelps wage subsidy is that Phelps would like to subsidize all low-wage workers. The EITC, however, is targeted at families with children—the subsidy is much smaller for workers without children. The EITC has been successful at increasing employment among single mothers but it doesn’t do much for single men.

In his book Rewarding Work, Phelps argues that wage subsidies are a better way to help low-skill workers than the minimum wage. We will return to this question in Chapter 8 when we take up price ceilings and price floors.