MOBILITY

10.2

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Identify the ways that migration has shaped the growth of cities, how cities have grown and changed, and how humans get around within cities.

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, we have entered an era when more people live in cities than rural areas: quite a historical feat. As we saw in the preceding section, when cities first sprung up, only a very small portion of the population lived in them. But over time, cities began to diffuse across the globe, and established cities grew larger. In this section, we look at the process of rural-to-urban migration that has, both in the past and today, fueled the growth of cities. Some cities have grown to a very large size, either in absolute population terms or relative to the other cities around them. We will take a look at where these very large cities are located, where they will appear in the future, and what role such cities play in a country’s urban hierarchy. The role of transportation in facilitating the movement of people within cities has also shaped the size and layout of cities. In this chapter, we focus particularly on the advent of the automobile and its central role in shaping human mobility in and between cities.

426

RURAL-TO-URBAN MIGRATION

The increase in urban population went hand-in-hand with the growing number of cities across the globe. In today’s world, however, increasing urbanization is caused by three related phenomena: natural population increase (see Chapter 3), rural-to-urban migration, and urban-to-urban migration. The last two phenomena can be domestic, as in a family moving from one city to another in the same country, or the result of international population movement from one country to another. Although the United Nations estimates that natural increase accounts for the majority of the recent growth in urban population, it was rural-to-urban migrations that historically brought millions of people into urban life.

As we have seen, wide-scale urbanization occurred hand-in-hand with industrialization. As capitalism took root and flourished, first in Europe and North America and subsequently shaping life everywhere in the world, cities allowed for the large workforces needed to run factories and to provide services of all sorts to factory owners and laborers. In the United States, rural-to-urban migration resulted in the growth of large cities such as Chicago in the nineteenth century, and large urban centers in Asia such as Tokyo and Mumbai in the twentieth century. Today, Europe and more recently North America as well as much of Latin America are highly urbanized societies, with about three-quarters of their populations living in cities. (See the World Heritage Site and Seeing Geography features in this chapter; both examine one of the largest cities in Latin America, Rio de Janeiro.)

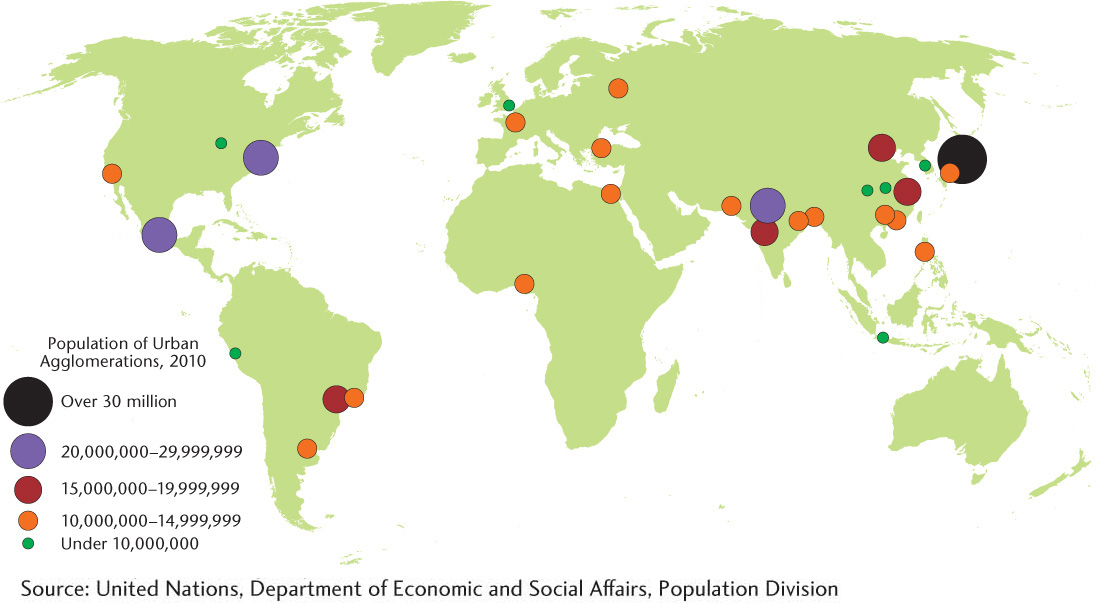

China presents a particularly interesting example of rural-to-urban migration. Until the late 1970s, the country was predominantly rural, and its communist government was explicitly anti-urban. Indeed, many urban Chinese were forced out of cities to work on farms during the decade of the Cultural Revolution from 1965 to 1975, under the logic that cities fostered class privilege. State policy reform after 1978 lifted restrictions on internal migration, which enabled its rural population to become more mobile. Many Chinese abandoned life in the countryside for futures in China’s booming industrial cities, among them Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Beijing. Note the number of Chinese cities that appear on the map of world megalopolises in Figure 10.17. Though just over 50 percent of China’s population is urban today, it is estimated that by 2025, 66 percent of China’s population will be urban, and there will be 221 Chinese cities with a population over 1 million. China’s “urban billion” is expected to materialize by 2030.

Today, particularly across Africa and Asia, large numbers of people still depart their rural villages and migrate to cities in search of better economic and social opportunities. The United Nations predicts that about four-fifths of the world’s future urban growth will result from rural-to-urban migration in these two regions. Others will be forced from their lands due to rural conflict, natural disaster, climate change, or seizure of their land. Thus, cities can increase in size not necessarily because there is economic growth requiring urban laborers, but rather because conditions in the countryside are dismal. People leave their farms and rural villages to escape economic, political, and environmental hardships, in the hope that urban life will offer a slight improvement. Often it does. Given the new global economy, however, many of the employment opportunities available in such cities are low-skilled and low-paying manufacturing and service jobs with harsh working conditions. The result is that rural-to-urban migrants often find themselves either unemployed or with jobs that barely provide a decent living (Figure 10.16).

427

WHEN ARE CITIES TOO LARGE?

Although rural-to-urban migration affects nearly all cities in the developing world, the most visible cases are the extraordinarily large settlements we call megacities, those having populations of over 10 million. Figure 10.17 shows the world’s 30 largest cities, a majority of which are located in the developing world. This is a major change from 50 years ago, when the list was dominated by Western, industrialized cities.

megacities

Particularly large urban centers.

The urban population in the developing world is growing at impressive rates. Indeed, the World Bank estimates that most of the urban growth in the world today—over 90 percent of it, in fact—is occurring in the developing world. Seventy million people move into cities in the developing world each year. The world’s two poorest regions, South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, expect their urban populations to double by 2030.

428

430

And with this incredible increase in the sheer numbers of urban dwellers in the less developed regions of the world comes a large list of problems. Unemployment rates in cities of the developing world are often over 50 percent for newcomers to the city; housing and infrastructure frequently cannot be built fast enough to keep pace with growth rates; water and sewage systems can rarely handle the influx of new people. Consequently, one of the world’s ongoing challenges will be how to cope with the radical restructuring of population and culture as people in developing countries move into cities.

World Heritage Site: Rio de Janeiro: Carioca Landscapes Between the Mountains and the Sea

World Heritage Site

Rio de Janeiro: Carioca Landscapes Between the Mountains and the Sea

This World Heritage Site encompasses a portion of the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. (Take a look also at Seeing Geography at the end of this chapter.) Specifically, it includes the natural elements located within the urban boundaries that have fundamentally shaped the city of Rio: the peaks of the Tijuca National Park, the Botanical Gardens established in 1808, and the hills surrounding Guanabara Bay. These distinctive urban landscapes have been celebrated artistically in paintings, poetry, song, and literature

◼ From 1763 to 1960, Rio de Janeiro was the capital of Brazil. In an effort to decentralize the national population away from the southeastern coast, the capital was relocated to Brasília, in the country’s interior (see Figure 5.30).

◼ Stretching from the mountains to the sea, this World Heritage Site is bounded by the best vantage points for appreciating the interaction of nature and culture.

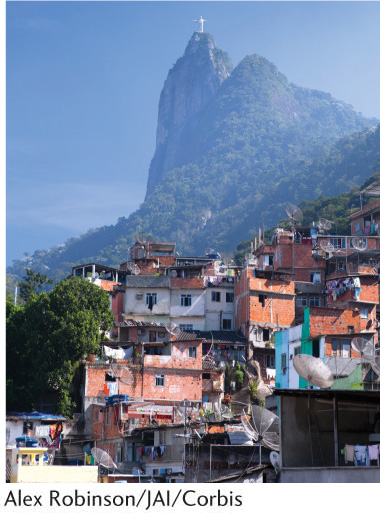

◼ As with many Latin American urban landscapes, Rio’s is one of expensive high-rise housing located immediately adjacent to favelas (slums).

429

CULTIVATING NATURE: The word Carioca refers to a resident of Rio de Janeiro. It is derived from the indigenous Tupi word for “houses of the whites,” referring to the Portuguese settlements built along the river in the sixteenth century c.e. Today, Carioca indicates both a dialect of Brazilian Portuguese, as well as the friendly, relaxed, and cosmopolitan personality associated with Rio de Janeiro. Carioca culture is defined by its outdoor living, framed by the beaches and mountains, but also the streets and parks. Urban planners have conscientiously highlighted the city’s dramatic local natural features, as well as enhanced them through landscaping and constructed elements of the urban environment.

◼ This World Heritage Site is home to the largest urban forest on the planet: the Tijuca Forest. It is but a remnant of the Atlantic forest ecosystem, which once extended along the length of Brazil’s coastline. From the founding of Rio in 1565 through the mid-1800s, trees were felled for timber and fuel for the expanding city. In 1860 Emperor Pedro II ordered the replanting of the forest with native species, acknowledging that the forest was essential for the city’s environmental and cultural well-being.

◼ Although it is known for its natural features, this site also includes low-income urban neighborhoods. With their tendency to be built on the city’s steep, forested hillsides, favelas such as Santa Marta put contemporary environmental pressures on the natural landscape.

TOURISM: Brazil hosted nearly 6 million foreign visitors in 2012. Frequently referred to as Cidade Maravilhosa (The Marvelous City), Rio de Janeiro is the country’s top destination for leisure travelers. It is widely described as one of the most beautiful cities in the world.

◼ Rio has been a global tourist attraction since the early 1900s when it constructed one of the world’s first aerial cable car lines to the top of a monolithic mountain called Sugar Loaf.

◼ Regardless of their religious affiliation, tourists from around the globe are keen to visit the world’s largest statue of Jesus, located on Corcovado Mountain in the Tijuca Forest.

◼ Rio de Janeiro hosted the World Cup soccer games in 2014 and will host the 2016 Summer Olympics. The city’s infrastructure is currently being upgraded to handle the expected influx of tourists.

◼ As with any large city, street crime is a concern. As of early 2014, assaults, theft, and muggings had increased dramatically in Rio in advance of the World Cup soccer games.

◼ Rio de Janeiro is known as one of the world’s most beautiful cities in great part because of how planners have showcased its dramatic natural features.

◼ This city is home to the world’s largest urban forest.

◼ The Carioca Landscapes Between the Mountains and the Sea were designated a World Heritage Site in 2012.

URBAN PRIMACY

The destination for much rural-to-urban migration in the developing world is the primate city. This is a city that, because it is so much larger than all others, dominates the economic, political, and cultural life of a country. Some scholars maintain that in order to qualify as a primate city, a city must be 10 times or more larger than the next largest city. With 13 million residents, Buenos Aires is an excellent example of a primate city because its population is exactly 10 times that of the next largest city, Rosario, which is the second largest city in Argentina with a population of 1.3 million. Although many developing countries are dominated by a primate city, often a former center of colonial power, urban primacy is not unique to these countries: think of the way London, Moscow, Athens, and Paris dominate their respective countries.

primate city

A city of large size and dominant power within a country.

These primate cities are often the ones that claim scholars’ and policy makers’ attention because of their dominance and large size. However, the United Nations finds that most of the world’s population lives in mid-sized cities of 500,000 or less. Indeed, the majority of urban growth today is taking place in smaller, less dominant cities. Urban planners and policy makers are beginning to focus their attention on these mid-sized cities scattered throughout the world, particularly in developing countries, in order to examine the impacts of increased urbanization.

This is true of the United States, too, where so-called legacy cities—well-known, established, large urban centers such as San Francisco, New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles—are not growing nearly as fast as mid-sized cities, particularly those located in the Sunbelt, known as “aspirational cities”—among them, Raleigh, Houston, Phoenix, San Antonio, and Las Vegas. Legacy cities have simply priced all but the elites out of their housing markets. Lower-skilled people are attracted to aspirational cities because they offer employment, affordable housing, and a lower cost of living. In 2012 Forbes flagged Houston as the United States’ “coolest city.” Youth (the typical Houstonian’s average age is 33), ethnic and racial diversity, and a growing slate of hip downtown amenities combined with employment and affordability have earned Houston this distinction (Figure 10.18).

URBAN TRANSPORTATION

Getting around inside the city, and transporting people and goods from city to city, has—for as long as cities have existed—been a major concern. You will recall that Rome was famous for its engineering marvels, including grid-patterned streets facilitating traffic flow within cities, and the remarkable network of roadways connecting cities across the Roman Empire.

431

Railroads, streetcars and trolleys, light rail systems, airplanes, busses, and subways have all presented innovations in urban transportation modes and infrastructure. These innovations have shaped and reshaped the layout and size of cities over time. For instance, the advent of streetcars—fixed rail systems within many U.S. cities that arose in 1880s—led to the development of so-called streetcar suburbs. Streetcar suburbs allowed urban residents to live farther away from their workplaces than they could in the past, when commuting was done by foot or horse.

streetcar suburbs

The extension of urban residential areas along streetcar lines in the late nineteenth century.

No innovation in transportation has had a more profound impact on cities, however, than the automobile. In the United States, Henry Ford’s mass-produced Model T initiated the norm of automobile ownership among the middle classes, and by 1920 over a million had been sold. Automobiles increased personal mobility exponentially, and it has been said that Henry Ford “freed common people from the limitations of geography.” Automobiles brought with them a network of roadways and, by the 1950s, interstate highways. Housing architecture was reshaped around the automobile with the addition of the now-ubiquitous garage. Drive-through commerce and architectural forms associated with it became a hallmark of America’s obsession with cars (Figure 10.19).

Because so much of the middle class owned a car, it became possible to locate housing further from the urban Central Business District (CBD), as its placement was not limited to locations close to existing train lines. As long as roads could be built to connect these settlements to the CBD, the new automobile suburbs would be viable. Cities grew ever-outward in a process that came to be known as sprawl (Figure 10.20). Some U.S. cities, such as Miami, Atlanta, Las Vegas, and Phoenix, are known as automobile cities because they have been significantly built up recently enough that their layouts are primarily oriented around cars.

central business district (CBD)

A dense cluster of offices and shops located at the city’s most accessible point, usually its center.

sprawl

The tendency of cities to grow outward in an unchecked manner, which is particularly notable in automobile cities.

automobile cities

Cities whose spatial layout—both in terms of extent and form— is dictated by the near ubiquity of individual automobile ownership.

432

THE DOWNSIDES TO URBAN CAR CULTURE

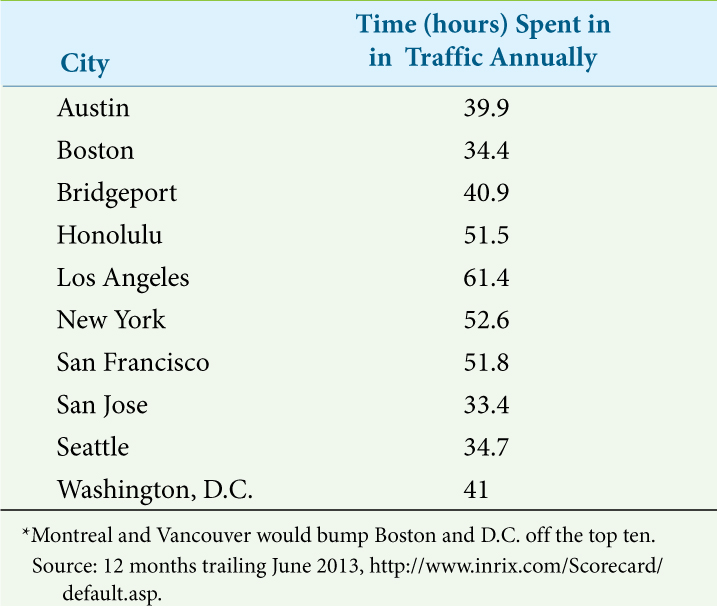

Automobiles also brought to cities undesirable aspects. Cities became increasingly polluted with the fossil fuel residue released by the automobile’s internal combustion engine, impacting the health of city residents. Safety, too, became a concern, and automobile fatalities—for both passengers and pedestrians—is the leading cause of accidental death. Traffic congestion is a major complaint, and many people squander time and money idling in traffic as they make their way to work, commuting from far-out suburban residences to workplaces (Table 10.1). In addition, the norm of individual commuters who spend a great portion of their day in a car has led to social isolation and inactivity. Some urban and suburban roads no longer have sidewalks, which has made pedestrian traffic—and the face-to-face social encounters seen by many sociologists to be at the heart of the urban experience—all but disappear.

In fact, there seems to be a growing disenchantment with automobiles, particularly among young people in Europe and the United States. French teenagers, for example, are less likely to hold a driver’s license: in 1983, 35 percent of 18- and 19-year-olds did, but by 2010 only 19 percent did. The numbers for U.S. teens show a similar decline, from 69 percent of 17-year-olds in 1983 to 46 percent in 2010. Researchers speculate that concerns over the costs of owning, operating, insuring, and maintaining a car have driven this decline, as has a disenchantment among today’s youth with the negative environmental impacts of automobiles along with a growing use of online technology as the preferred way to connect with friends.

This phenomenon has led to a rise in alternate modes of urban transportation. So-called millennials—teens and people in their twenties—are opting to bike or take public transportation rather than to drive or even own cars. Car- and bike-sharing services have sprung up in cities across the globe (Figure 10.21). For a nominal fee, a user can avoid the cost and hassle of owning a bike or car, and simply rent it for the time needed, or subscribe for a monthly fee. In the United States, reservations and payment are often made through smartphones and the user simply parks the vehicle at a rental station when done. In Europe, the process is even more flexible, as drivers locate the nearest available car using their smartphone and simply pick up the vehicle wherever in the city the previous user parked it. As a result, fewer people own cars, and fewer families own more than one car, which reduces the need for parking spaces and curtails pollution.

433