GLOBALIZATION

11.3

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Analyze the relationship of contemporary globalization to historical processes and its likely effects on the future.

How does globalization operate to shape the future? How does it relate to phenomena of the past, such as European colonialism? These are some of the questions geographers and other scholars are investigating in their research. We can start by looking at some of this groundbreaking work.

UNDERSTANDING THE FUTURE EFFECTS OF GLOBALIZATION THROUGH THE PAST

American Commodities in an Age of Empire, Mona Domosh’s book on the United States’ unique form of imperialism, illustrates the continuities between historical experience and globalization’s future. Domosh shows how U.S. overseas imperialism was conducted not through military conquest and occupation, but through the international commercial activities of private corporations. By 1915 U.S. companies dominated all aspects of world trade. Many of them had established overseas manufacturing, developed international sales and financial networks—aided greatly by global telegraph communications—and functioned in a way that disregarded political borders. In other words, the early-twentieth-century international business looked a lot like what we call globalization.

Domosh’s book provides historical evidence for thinking about the future of cultural difference under globalization. For example, in the early twentieth century, U.S. companies in search of international profits needed to market their commodities—soap, tractors, sewing machines, and much more—to a wide variety of cultures. Domosh shows how companies used existing categories of racial difference to pitch their products by offering the promise of transformation. That is, by consuming U.S. products, the Chinese, Indian, or African individual could become more modern and civilized. This is the paradox of global advertising. Cultural differences are highlighted with the promise of their erasure through the consumption of mass-produced commodities. See the World Heritage site for a historical look at the origins of globalization.

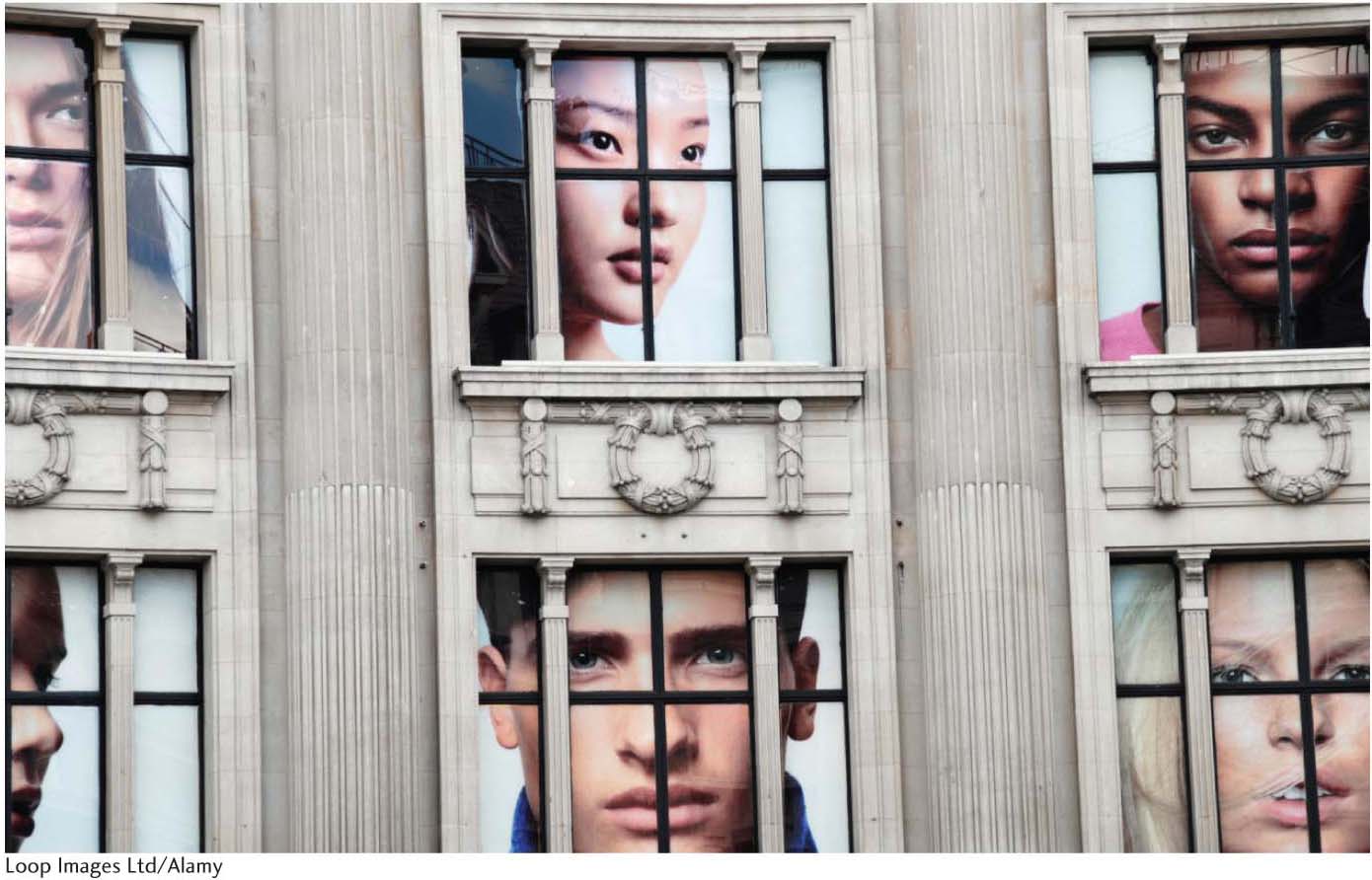

We can think of any number of advertising campaigns today that operate with a logic similar to that of early-twentieth-century international marketing. From soft drinks, to clothing, to automobiles, global advertising highlights cultural difference while promising unity through consumption. Of course, in today’s ads the crude racial stereotypes and hierarchies of the past are nowhere to be seen, or are at least tucked well below the surface. Indeed, multiculturalism is celebrated in a sort of unity-in-diversity. The Italian multinational clothing firm United Colors of Benetton is renowned for this advertising strategy (Figure 11.17).

474

476

Geographers are interested in globalization because it bears so profoundly on the central geographical issue of human diversity. It produces a multitude of historically unique, contradictory, and paradoxical cultural conditions. The most evident paradox is that globalization—which would seem to erase cultural difference—has been accompanied by a reassertion of distinct religious, national, and ethnic identities. The start of the twenty-first century has been marked by heightened ethnic divisions and conflicts, the resurgence of nationalism, and numerous highly visible identity movements—gay, feminist, green, and religious fundamentalist. Contradictions and paradoxes such as these lead many geographers to conclude that the future effects of globalization will not be predominantly homogenizing. Moreover, people are self-aware actors who may view, for many different reasons, the effects of globalization as something that should be resisted or defended against.

World Heritage Site: Cidade Velha, Historic Centre of Ribeira Grande

World Heritage Site

Cidade Velha, Historic Centre of Ribeira Grande

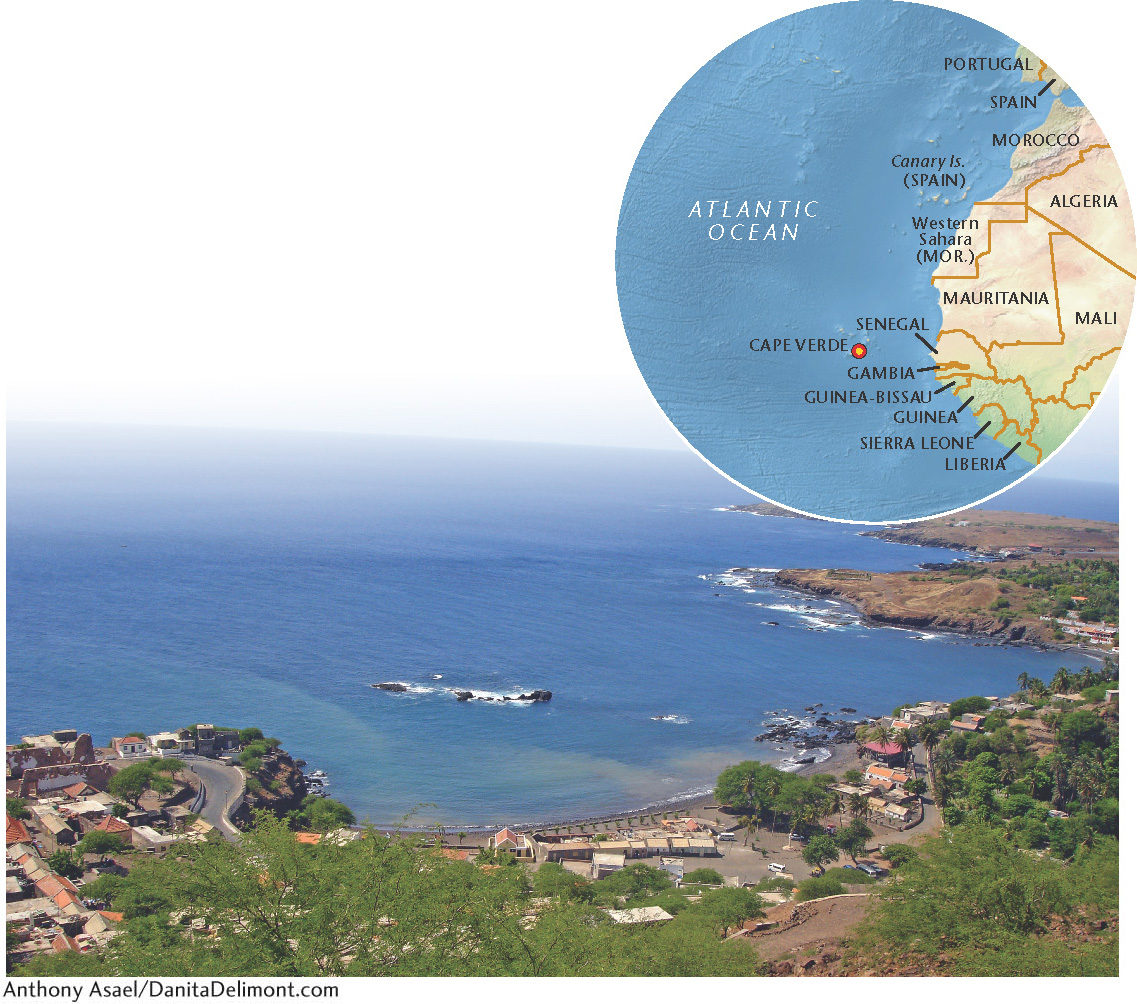

Cidade Velha, Historic Centre of Ribeira Grande, preserves a key location of globalization’s origin. Ribeira Grande was the first European colonial town in the tropics. If globalization is the force shaping our present and future, globalization itself has roots in the heritage preserved at Ribeira Grande. Inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 2009, it was selected as an early image of transcontinental geopolitical visions.

◼ Portuguese maritime explorers discovered then uninhabited Santiago Island in the Cape Verde archipelago in 1460. They established the port city of Ribeira Grande on its southern shore a few years later. Commercial activity shifted to the newer port of Praia in the 1700s. Ribeira Grande was salvaged for building materials and renamed Cidade Velha (old town).

◼ Ribeira Grande was a major crossroads for Portuguese maritime trade, which very quickly became globalized. By the mid-1500s, fleets from Africa, India, Brazil, southeast Asia, and Europe traveled there to trade cargos and information.

◼ Because of its geostrategic location in relation to Europe, Africa, and the Americas, Ribeira Grande became a key connection in the African slave trade. Europeans brought African slaves to the port where they were traded in the slave market and then shipped to the Americas. it was also a key location of global plant exchange and agricultural experimentation that combined enslaved labor with the cultivation of imported tropical and subtropical crops.

◼ The blending of European and African cultures from the fifteenth century onward gave birth to the world’s first Creole culture, now familiar throughout the Caribbean region. Languages, religions, foods, architectures, and music from the two continental traditions have mixed on Santiago to create a distinct Cape Verde Creole culture.

475

IN OLD TOWN: when the Portuguese relocated commerce and government to Praia, they dismantled many of Ribeira Grande’s historic structures for use in building the new port. However, some residents stayed behind and key elements of the old town’s design and architecture have endured for centuries.

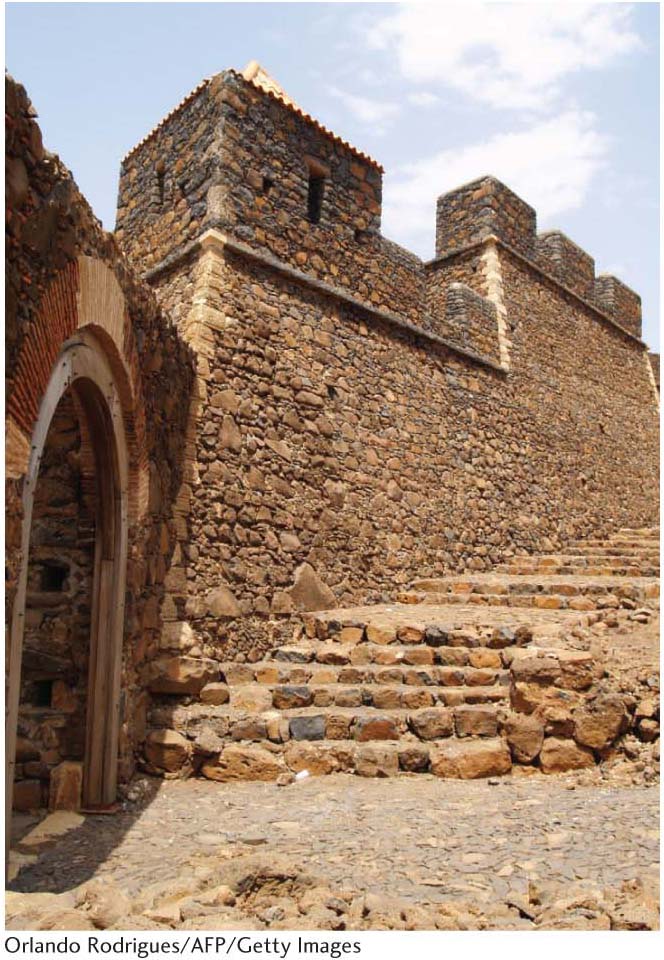

◼ The great wealth concentrated at this colonial outpost attracted the unwanted attention of mariners from competing European countries. Thus, the old town features the ruins of an elaborate system of walls and forts. After Sir Francis Drake sacked Ribeira Grande in 1585, the Portuguese fortified their defenses by building the royal fortress of São Felipe in 1593, known then as one of the world’s strongest. It has been partially restored.

◼ The Portuguese centered the old town on Pillory Square, so named for the marble column raised in the early 1500s. The pillory is the oldest remaining monument of the town and was installed to symbolize Portuguese power and authority. Recalcitrant slaves were publically punished at the pillory. It is one reason Ribeira Grande became part of UNESCO’s Slave Route project, an initiative to promote important memorials and places in the African slave trade.

◼ Ribeira Grande featured many religious buildings including churches and chapels, a cathedral, and a convent. Only the church of Nossa Senhora do Rosário, dating from the late fifteenth century, and the chapel of the Convent of São Francisco, built in the seventeenth century, exist in restored condition. The remainder of the site’s religious buildings are in ruins or consist only of archaeological artifacts. Of the cathedral, only its walls, constructed in the mid-sixteenth century from stone imported from Portugal, stand today.

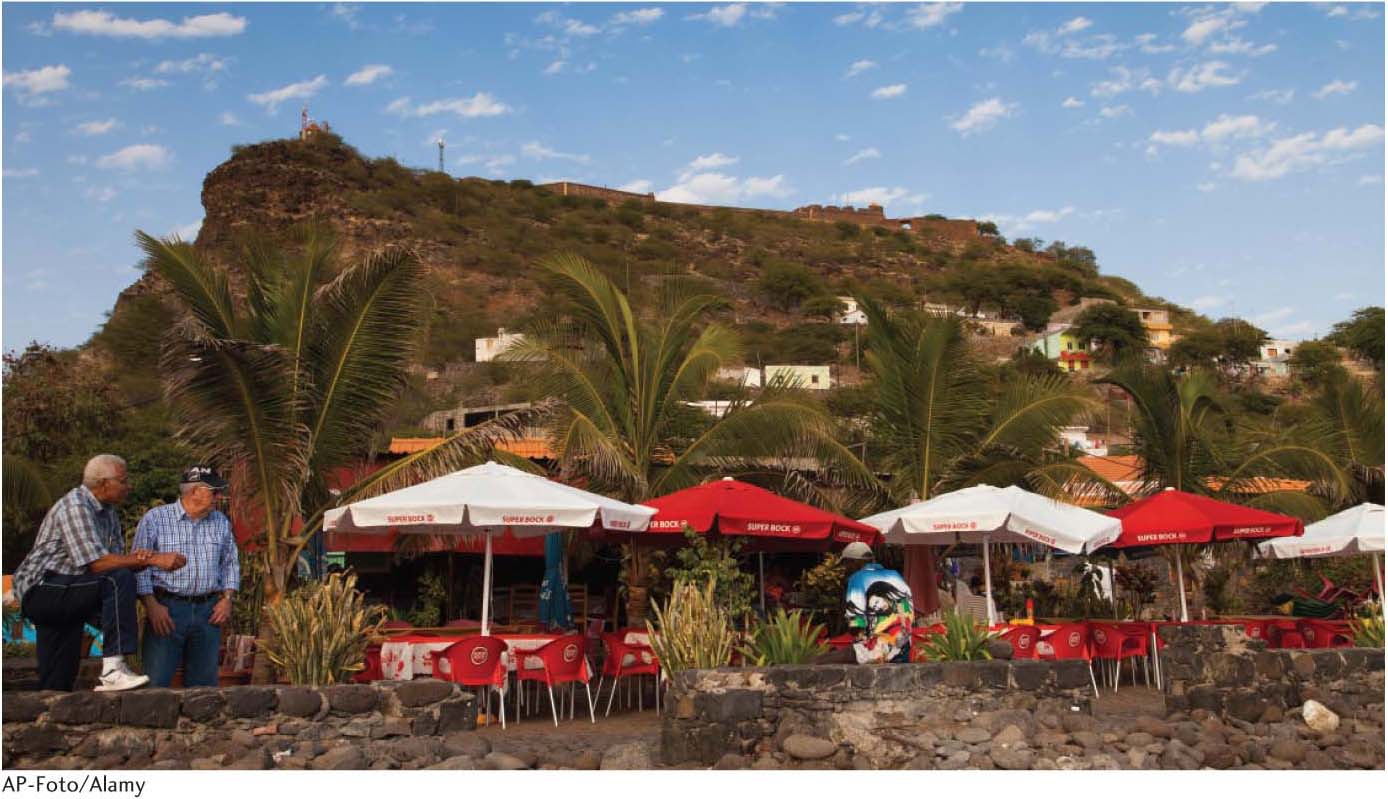

TOURISM: Cidade Velha is a short distance from Praia, the capital city of the Republic of Cabo Verde, which is served by ferries and an international airport. Tourism is one of the republic’s most important industries.

◼ The historic ruins of the fifteenth-century church and the royal fortress, the old stone houses, and Pillory Square are main draws for tourist traffic.

◼ The local tourism industry in Cidade Velha is relatively underdeveloped and the Cabo Verde government has only recently attempted to encourage it. while the site has tourist appeal due to the antiquity of the town and stunning island location, it is also tainted by its association with slavery.

◼ Some might label a trip to Cidade Velha as a form of “dark tourism” because of the site’s central role in the horrific history of the global trade in African slaves. However, UNESCO’s Slave Route project terms it “memorial tourism,” encouraging host countries to promote such sites for educational purposes and to memorialize the lives lost.

◼ Cidade Velha, in the Cape Verde Islands, was Europe’s first tropical colony and a major crossroads for global maritime trade by the early 1500s.

◼ The site features many defensive fortifications, reminders of its former status as one of the world’s wealthiest trading outposts.

◼ Cidade Velha is part of UNESCO’s Slave Route project, an initiative to preserve sites of the African slave trade and promote “memorial tourism.”

GLOBALIZATION AND ITS DISCONTENTS

Some of the features of globalization—the consolidation of transnational corporate power, global environmental change, the spread of consumer culture to every corner—are viewed by people worldwide as threatening to established values, ways of life, and economic livelihoods. For many people, the future under globalization does not look bright. As geographer Matt Sparke observes, responses to globalization or to globalization’s effects come in many forms and from disparate political corners. From the right comes ultra-nationalist reaction, which includes calls for protection of national industries against global competition and limits to immigration and migrant rights. France’s National Front, led by Marine Le Pen, exemplifies the response from the right. In a 2013 speech, Le Pen compared globalism to a “totalitarian” ideology and called “for Europe to halt immigration.” Religious conservatives also strongly react against globalization. Osama bin Laden viewed many aspects of the global economy as violating the sacred teachings of the Qur’an, as do present-day Islamic leaders associated with al-Qaeda. As Sparke noted, there is an obvious contradiction between al-Qaeda’s opposition to globalization and its use of global networks of communication and terrorist training.

On the political left are critics who see globalization as leading to a future of increased economic inequalities across all geographic scales and increased empowerment of transnational corporations at the expense of local access and control. The left calls for checks on unfettered trade liberalization to strengthen worker rights, for greater focus on and access to public services and spaces, and for the enhancement of local food security. The position on the left is oriented more toward altering the way globalization operates than toward simple opposition. The Occupy movement that started as a protest in 2011 in New York City’s financial district, Wall Street, and has since grown internationally is a good example. The movement slogan, “We are the 99%,” is meant to signify that globalization has led to the enrichment of a tiny minority while negatively impacting an overwhelming majority. Through the strategic use of social media such as Twitter and Facebook, the Occupy movement very quickly moved from Wall Street to a global network that organized a day of street protests in cities around the world.

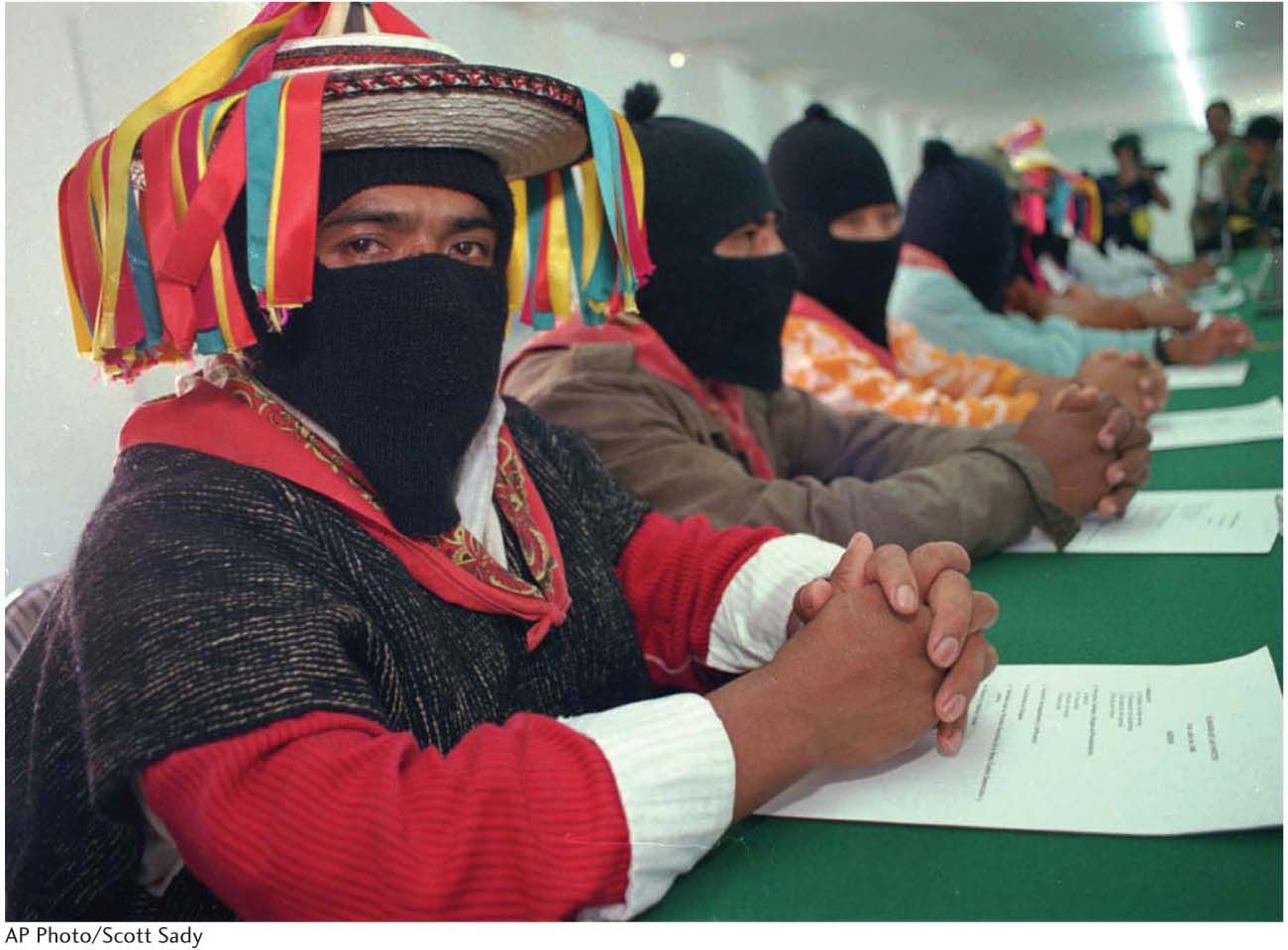

The indigenous rights movement is difficult to classify on the left to right political spectrum, but it has nevertheless presented a constant challenge to economic globalization. Mexico’s Zapatistas are a good example. On January 1, 1994—the day that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) among Canada, the United States, and Mexico took effect—hundreds of indigenous Mayan peasants forcibly occupied government offices in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas. Calling themselves Zapatistas, they declared that they had no choice but to take up arms (Figure 11.18). The impoverished Mayan farmers saw globalization in the form of NAFTA as sounding the death knell for their culture and way of life. Globalization meant that cheap corn from the midwestern region of the United States would flood Mexico, making it impossible for Mayans to continue farming for a living and to maintain their communities. Interestingly, the initial armed rebellion soon gave way to a skillful campaign that used key instruments of globalization—satellite TV and the Internet—to gain worldwide support for their campaign. The Zapatistas have won some concessions from the Mexican government, but their struggle to protect their culture and homeland continues. Check their web site or follow them on Twitter for details on the latest developments.

477

Many more examples of efforts to resist globalization or at least mitigate its worst effects could be recounted. Some movements mobilize globally; others, locally. Some movements take up arms; others work through existing democratic institutions. In most cases, however, these movements seek to gain a voice in altering and controlling the speed and extent of globalization’s transformative forces. As a consequence, the effects of globalization are not predetermined; cultural homogeneity is not the only possible outcome. Rather, the actions of local culture groups—be they indigenous peoples, urban workers, or rural farmers—also shape its effects. The local-global link, it seems, operates in two directions to shape an unfolding future.

BLENDING SOUNDS ON A GLOBAL SCALE

On the popular music scene, debates about the effects of globalization abound. These debates follow the general terms of the broader globalization debates. Is globalization a force for homogenization or new forms of diversification, hybridity, and synthesis? If we think about music historically, synthesis and hybridization have deep roots. It is actually fairly difficult to find a truly “authentic” or “pure” locally bound musical genre that has not been influenced by extra-local musical forms. Distinctive regional sounds, such as Memphis soul or Tibetan throat singing, can definitely be identified. In many cases, these musical genres are associated with culture regions. At the same time, musical genres rarely develop in geographic isolation. Prior to globalization, migration and movement produced all manner of blending of ideas, styles, and genres— probably since the time humans began imitating the rhythms and sounds of nature. Modern technological innovations, from the invention of the gramophone to the release of online file-sharing software, have accelerated, intensified, and added to the complex processes of musical hybridization.

Take the case of soukous, a musical genre centered in Africa’s Congo River basin. Soukous originated in the folk music and dance traditions of various Congolese ethnic groups. Some of these performers began to adopt Western instruments and jazz arrangements during the period of Belgian colonization in the early twentieth century. As the population urbanized in the 1950s, record companies found a burgeoning market and began importing Cuban “rumba” 78-rpm vinyl recordings. These “Latin” rhythms were incorporated and helped launch soukous as the first pan-African sound. It is interesting to note that this transfer was part of a historical process of multidirectional diffusion, since the rhythms imported from Cuba originated among African slave laborers who had carried them from West Africa a century earlier. Congolese musicians were given record contracts and brought to Paris studios, where they continue to blend new sounds and techniques and pump out the pulsing soukous beat for the world music scene. One can get dizzy just trying to keep track of the many multidirectional pathways of cultural interaction across time and space.

478

Cultural interaction in music has been ongoing for centuries but has been greatly speeded up and geographically expanded under globalization. From one perspective, globalization has sparked a creative cultural interaction by mixing musical traditions from around the world to produce new hybrid forms, many of which are highly localized. As a result, new and innovative regionally based soundscapes emerge continuously, reinforcing old or helping to construct new culture regions. From another perspective, globalization has enriched First World transnational entertainment corporations without providing due compensation for the creative labor of local cultures. The debate over which perspective best reflects the actual effects of globalization on music is complex and will undoubtedly continue.